The Beijing Museum of Natural History stands as a testament to China’s rich paleontological heritage, housing some of the most significant fossil discoveries of our time. Among its treasures, the collection of feathered dinosaur fossils represents a revolutionary chapter in our understanding of avian evolution. These remarkable specimens, many unearthed from China’s fossil-rich provinces, provide compelling evidence of the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and modern birds. As visitors wander through the museum’s carefully curated halls, they embark on a journey spanning hundreds of millions of years, witnessing the tangible connections between Earth’s ancient past and its present biodiversity.

The Origins of Beijing’s Natural History Museum

Founded in 1951, the Beijing Museum of Natural History emerged as China opened itself to scientific inquiry and public education about the natural world. The museum initially occupied a modest space with limited collections, focusing primarily on showcasing local flora and fauna. Through decades of development and several relocations, it eventually found its permanent home in the Dongcheng District of Beijing, where it has grown into one of Asia’s premier natural history institutions. The current building, completed in 2006, features modern exhibition spaces specifically designed to highlight China’s paleontological treasures. With over 200,000 specimens in its collections, the museum represents China’s commitment to preserving and studying its natural heritage while making these scientific discoveries accessible to the public.

The Jehol Biota: Window to a Prehistoric World

One of the museum’s crown jewels is its extensive collection from the Jehol Biota, a 130-million-year-old ecosystem preserved in northeastern China’s Liaoning Province. This remarkable fossil assemblage represents one of the most complete prehistoric ecosystems ever discovered, capturing plants, insects, fish, amphibians, reptiles, and early mammals in exceptional detail. The Jehol deposits gained international fame for their preservation of soft tissues, including skin impressions, internal organs, and most notably, feathers. The fine-grained sedimentary rocks, formed from ancient lake beds, created perfect conditions for preserving even the most delicate structures. The museum’s Jehol exhibition allows visitors to witness an entire Cretaceous ecosystem frozen in time, offering insights into ancient food webs, habitats, and evolutionary relationships that would otherwise remain lost to history.

Sinosauropteryx: The First Feathered Dinosaur

In 1996, the paleontological world was forever changed when Chinese scientists announced the discovery of Sinosauropteryx, the first non-avian dinosaur found with definitive evidence of feathers. The Beijing museum proudly displays one of the finest specimens of this groundbreaking discovery. Sinosauropteryx was a small, carnivorous dinosaur roughly the size of a turkey, with preserved impressions of primitive, hair-like feathers covering its body and tail. These structures, technically called “protofeathers,” were not used for flight but likely served for insulation or display. The specimen’s remarkable preservation allows visitors to see the distinctive orange and white banding pattern of the feathers, representing some of the first evidence of dinosaur coloration. This single fossil fundamentally altered scientific understanding of dinosaur appearance and provided crucial evidence supporting the dinosaur-bird evolutionary connection.

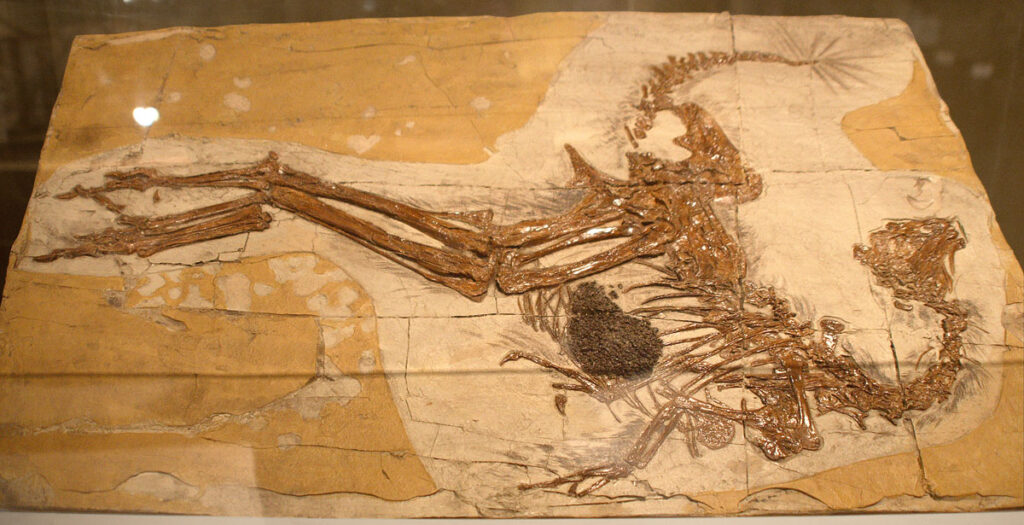

Microraptor: The Four-Winged Dinosaur

Perhaps the most visually striking of all feathered dinosaurs on display is Microraptor, a crow-sized predator that lived approximately 120 million years ago. This extraordinary creature possessed not just two but four wings, with long flight feathers extending from both its arms and legs. The museum’s specimens show these features in exceptional detail, preserved in the dark, carbon-rich impressions against the pale stone matrix. Paleontologists believe Microraptor used these four wings to glide between trees in ancient forests, representing an evolutionary experiment in flight different from the path that led to modern birds. The animal’s iridescent black feathers, determined through microscopic analysis of fossilized melanosomes (pigment-bearing structures), suggest it had glossy plumage similar to modern crows or ravens. Microraptor exemplifies the museum’s ability to showcase not just the existence of feathered dinosaurs but the diversity of their adaptations.

Yi Qi: The Dinosaur with Bat-like Wings

Among the museum’s most enigmatic specimens is Yi qi (pronounced “ee-chee”), whose name means “strange wing” in Mandarin. This chicken-sized dinosaur, discovered in 2007 and described in 2015, represents one of the most unusual flight adaptations ever documented in the fossil record. Unlike other feathered dinosaurs, Yi qi possessed a long, rod-like bone extending from each wrist that appears to have supported a membranous wing similar to those of modern bats. The museum’s specimen clearly shows both the preserved feathers covering the animal’s body and the impressions of these membranous wings. This bizarre combination of features suggests that dinosaurs experimented with multiple forms of flight before the bird-like arrangement of feathered wings became dominant. Yi Qi provides compelling evidence that evolution explored numerous pathways in the development of vertebrate flight, many of which ultimately proved evolutionary dead ends.

Anchiornis: Reconstructing Dinosaur Colors

The museum’s specimen of Anchiornis huxleyi represents a scientific milestone as the first dinosaur for which researchers could reconstruct a complete color pattern. This crow-sized feathered dinosaur lived approximately 160 million years ago, predating Archaeopteryx, the earliest recognized bird. Through advanced microscopic analysis of fossilized melanosomes preserved in the feathers, scientists determined that Anchiornis had a primarily grey body with white-feathered wings featuring black spots, and a rufous red crown on its head. The museum’s display includes both the remarkably preserved fossil and a full-color reconstruction showing this striking plumage pattern. This scientific breakthrough, featured prominently in the museum’s exhibits, demonstrates how modern analytical techniques can extract previously unimaginable details from well-preserved fossils. Anchiornis helps visitors understand that dinosaurs were not the drab, monotone creatures once depicted but vibrant animals with complex coloration serving social and ecological purposes.

Yutyrannus: The Feathered Tyrant

Standing in stark contrast to the smaller feathered dinosaurs is Yutyrannus huali, whose name translates to “beautiful feathered tyrant.” This massive predator, reaching lengths of over 30 feet, represents the largest known dinosaur with confirmed feathers. The Beijing museum’s specimen demonstrates that even large tyrannosaurs possessed feathery coverings, challenging the long-held assumption that only smaller dinosaurs had feathers. Yutyrannus lived approximately 125 million years ago in a relatively cool climate, suggesting its feather coat may have provided crucial insulation. The long, filamentous feathers preserved on the fossil extend up to 8 inches in length, creating what would have been a shaggy, mane-like appearance in life. This impressive specimen serves as a powerful reminder that feathers evolved long before flight and initially served functions related to insulation and display rather than aerial locomotion.

Caudipteryx: The Peacock Dinosaur

Among the most visually distinctive feathered dinosaurs in the museum’s collection is Caudipteryx, a turkey-sized omnivore that lived approximately 125 million years ago. What makes Caudipteryx immediately recognizable is its fan-shaped arrangement of long tail feathers, reminiscent of a modern peacock’s display. Unlike many feathered dinosaurs, where impressions must be carefully examined, Caudipteryx specimens show unmistakable feather preservation that even untrained visitors can easily identify. The museum’s specimen displays not only the tail feathers but also the wing feathers on its short arms, which were too small for flight but likely used in display behaviors. Detailed studies of Caudipteryx anatomy revealed remarkably bird-like features, including gastroliths (stomach stones) preserved where the stomach would have been, indicating it processed food similarly to modern birds. This combination of distinctive display feathers and bird-like digestion makes Caudipteryx a crucial evolutionary link that helps visitors understand the incremental changes leading from dinosaurs to birds.

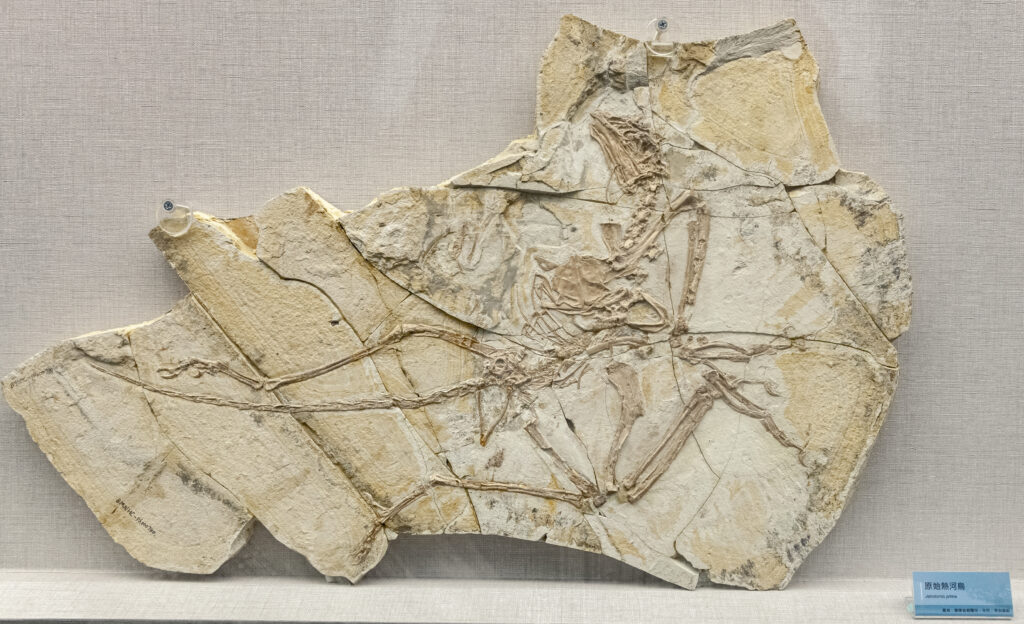

The Confuciusornis Sanctus Collection

Moving beyond dinosaurs to early birds, the museum houses an unprecedented collection of Confuciusornis sanctus specimens, making it the world’s foremost repository for this crucial early bird species. Confuciusornis lived around 125 million years ago and represents one of the first birds to evolve a toothless beak, similar to modern birds but different from toothed early birds like Archaeopteryx. The museum’s collection includes over fifty individual specimens, allowing researchers and visitors to observe variations across multiple individuals. Many male specimens display remarkable paired tail feathers that could extend up to 20 centimeters beyond the main tail, likely used for mating displays. These specimens are presented in various postures, with some showing wings spread as if in flight and others preserved in resting positions. The abundance of Confuciusornis fossils provides insights into early bird social behavior, suggesting these animals may have lived and died in flocks, much like many modern bird species.

Ancient Mammals: Beyond the Dinosaurs

While feathered dinosaurs represent the museum’s most famous fossils, its collection of ancient mammal specimens provides equally important insights into evolutionary history. The museum houses several specimens of Repenomamus, a badger-sized mammal that lived alongside dinosaurs approximately 125 million years ago. One spectacular specimen even preserves the remains of a small dinosaur in its stomach contents, proving that not all mammals during the “Age of Dinosaurs” were small, shrew-like creatures avoiding predation. The museum also displays numerous specimens of early gliding mammals like Volaticotherium, which developed skin membranes for gliding between trees millions of years before bats evolved true flight. These mammal fossils, presented alongside their dinosaurian contemporaries, help visitors understand the complex ecosystem of Mesozoic China, where early mammals were developing their evolutionary innovations even while dinosaurs dominated the landscape. The exceptional preservation of these specimens allows scientists to study soft-tissue anatomy rarely found in mammal fossils from other parts of the world.

The Ancient Aviary: Early Bird Evolution

Beyond Confuciusornis, the museum houses an extensive collection of other early birds that help document the radiation of avian species following their divergence from dinosaurian ancestors. The collection includes specimens of Jeholornis, one of the earliest birds to develop seeds as a primary food source, evidenced by preserved stomach contents showing thousands of tiny seeds. Visitors can also examine fossils of Sapeornis, an early bird that retained primitive features like wing claws while developing more modern flight capabilities. Particularly significant is the museum’s collection of enantiornithines or “opposite birds,” a major group of early birds that were once widespread but disappeared along with non-avian dinosaurs during the end-Cretaceous extinction. These specimens, some preserving delicate features like foot scales and wing membranes, demonstrate that bird evolution wasn’t a simple linear progression but a complex branching process with numerous evolutionary experiments. The collection’s breadth allows the museum to present the story of bird evolution with unprecedented completeness, from dinosaurian ancestors to recognizably modern forms.

Conservation and Research: Preserving China’s Fossil Heritage

Behind the public exhibits, the Beijing Museum of Natural History maintains state-of-the-art conservation facilities where paleontologists and technicians work to preserve and study newly discovered specimens. The museum employs specialized imaging technologies, including CT scanning and laser surface mapping, to examine fossils without damaging them, creating detailed three-dimensional models that can be studied and shared globally. A dedicated preparation laboratory allows visitors to observe technicians removing matrix rock from newly discovered fossils, providing a glimpse into the painstaking work required to reveal delicate preserved structures. The museum also houses a comprehensive digital database of its collections, contributing to international research networks and collaborative studies. Through partnerships with universities and research institutions across China and internationally, the museum serves as more than a display space—it functions as an active research center advancing our understanding of evolutionary history. These conservation efforts ensure that China’s remarkable fossil heritage will remain available for scientific study and public education for generations to come.

The Future of Paleontology: New Discoveries and Technologies

The Beijing Museum of Natural History continues to expand its collections as new fossil discoveries emerge from China’s rich paleontological sites. Recent additions include specimens utilizing advanced preservation techniques that maintain the three-dimensional structure of fossils rather than flattening them between rock layers. The museum has embraced digital technologies, creating virtual reality experiences that allow visitors to “fly” alongside reconstructed feathered dinosaurs or walk through Cretaceous forests. Ongoing research projects at the museum include detailed studies of feather evolution using electron microscopy and chemical analysis to understand the development of feather structures at the molecular level. The museum has also developed traveling exhibitions that bring casts and replicas of its most significant specimens to international audiences, spreading awareness of China’s contributions to paleontological science. As new analytical techniques develop, specimens that have been in the collection for decades continue to yield new information, demonstrating the enduring scientific value of these ancient remains. The museum stands at the forefront of paleontological research, where each new fossil has the potential to rewrite our understanding of life’s evolutionary history.

Conclusion

The Beijing Museum of Natural History’s collection of feathered dinosaurs and ancient birds represents one of humanity’s most significant windows into evolutionary history. These exquisitely preserved specimens have transformed our understanding of dinosaurs from scaly reptiles to dynamic, feathered creatures that still exist today in the form of modern birds. As visitors walk through the museum’s halls, they witness not just static displays of ancient bones but the compelling evidence of evolution in action—the gradual transformation of dinosaurian features into avian ones, with feathers appearing long before flight evolved. In preserving and presenting these priceless fossils, the museum fulfills a dual mission: advancing scientific understanding through research while making these discoveries accessible to the public, connecting people across generations to the wonder of our planet’s extraordinary past.