The Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences stands as one of the oldest and most respected geological museums in the world. Nestled within the historic University of Cambridge, this remarkable institution houses over 2 million fossils, rocks, minerals, and other geological specimens that span the entire history of our planet. Named after the pioneering geologist Adam Sedgwick, the museum represents not just a collection of ancient objects, but the very foundation upon which modern paleontology was built. From Darwin’s specimens to massive dinosaur skeletons, the Sedgwick offers visitors a journey through time that begins with Earth’s formation and continues through the development of scientific thought itself. As we step inside this venerable institution, we discover not only prehistoric treasures but also the human stories of discovery, debate, and determination that shaped our understanding of life’s ancient history.

The Legacy of Adam Sedgwick: The Museum’s Namesake

Adam Sedgwick (1785-1873) stands as one of the most influential figures in the development of geological science, and his legacy lives on through the museum that bears his name. As the Woodwardian Professor of Geology at Cambridge University from 1818 until his death, Sedgwick transformed the understanding of Earth’s history during a pivotal time in scientific development. He was instrumental in defining the Cambrian period and conducted groundbreaking fieldwork throughout Britain that established fundamental principles of stratigraphy. Interestingly, Sedgwick served as Charles Darwin’s mentor during Darwin’s early geological training, though the two would later disagree about evolutionary theory. Sedgwick’s personal collection formed the nucleus of what would become the museum, beginning with just a few hundred specimens but growing exponentially through his tireless collection efforts and academic connections. His pedagogical approach—emphasizing direct observation of specimens rather than merely theoretical study—continues to influence the museum’s educational philosophy today.

Architectural Marvel: The Building’s Design and History

The Sedgwick Museum resides in the Downing Site of Cambridge University within a purpose-built Edwardian structure that stands as an architectural testament to the importance of natural sciences in academic life. Completed in 1904, the building features a distinctive neo-Jacobean style with red brick facades and ornate stonework that immediately signals its historical significance. The interior showcases a magnificent two-story gallery with an oak balcony and original Victorian and Edwardian display cases that have been carefully preserved throughout the museum’s history. Natural light floods through large windows, illuminating the specimens in a way that modern museum designers often attempt to recreate with artificial lighting. The building itself was funded by a £20,000 bequest from Thomas McKenny Hughes, Sedgwick’s successor as Woodwardian Professor, demonstrating the personal investment many early geologists made in preserving their scientific legacy. Despite renovations to improve accessibility and conservation conditions, the museum has maintained its historical character, allowing visitors to experience the collections in an atmosphere similar to what scientists and students would have encountered a century ago.

Darwin’s Specimens: Tracing the Voyage of the Beagle

Among the Sedgwick’s most treasured possessions are the rock and fossil specimens collected by Charles Darwin during his transformative voyage aboard HMS Beagle (1831-1836). These specimens represent more than mere historical curiosities—they are the physical evidence that helped shape Darwin’s revolutionary ideas about natural selection and geological processes. Visitors can observe the very rocks Darwin collected from the Galapagos Islands, specimens that puzzled him with their volcanic origin and contributed to his understanding of geological uplift and the age of Earth. The collection includes fossilized remains that Darwin carefully documented in South America, noting their similarities to living species while recognizing crucial differences that would later inform his evolutionary theories. Each specimen is accompanied by Darwin’s original field notes and sketches, providing insight into his methodical approach and developing thought process. The Sedgwick Museum has meticulously preserved these items, ensuring that contemporary researchers can still study the actual materials that sparked one of science’s greatest paradigm shifts, while educational programs help visitors understand how these specimens fit into the broader narrative of scientific discovery.

The Geological Timeline: Walking Through Earth’s History

The Sedgwick Museum offers visitors a remarkable opportunity to physically walk through Earth’s 4.5-billion-year history via its thoughtfully arranged main gallery. Beginning with the oldest rocks dating to the Precambrian era—some approaching 3.8 billion years in age—the chronological arrangement guides visitors forward through time with each step representing millions of years of Earth’s development. Glass cases display carefully selected specimens that illustrate the key evolutionary and geological changes of each period, from the Cambrian explosion of complex life forms to the rise and fall of dinosaurs during the Mesozoic era. The timeline culminates with the relatively recent Quaternary period, highlighting the emergence of early humans and the ice ages that shaped our modern landscape. Color-coded displays and interactive touchscreens help visitors understand the relative timeframes involved, making comprehensible the otherwise difficult concept of deep time. This walkable timeline serves as the museum’s conceptual backbone, providing context for all other exhibits and demonstrating how geological and biological evolution are inextricably linked throughout Earth’s long history.

Extraordinary Fossils: The Crown Jewels of the Collection

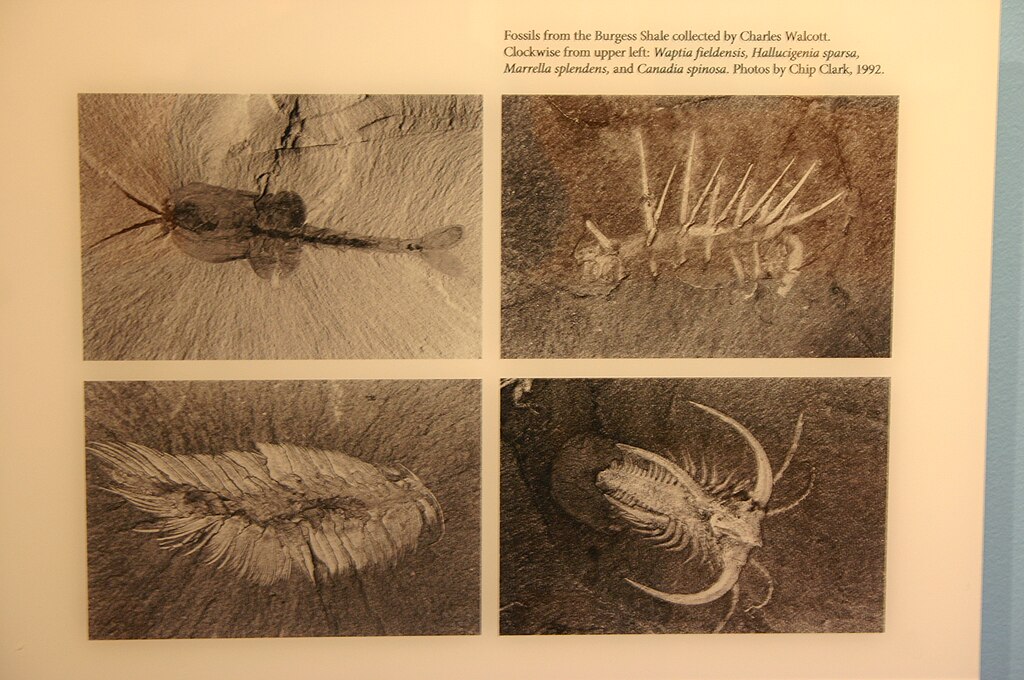

The Sedgwick Museum houses some of paleontology’s most significant fossil specimens, each representing pivotal discoveries in our understanding of prehistoric life. The crown jewel might be considered the nearly complete Iguanodon skeleton, one of the first dinosaurs ever scientifically described and a specimen that helped establish dinosaurs as a distinct taxonomic group rather than merely oversized lizards. Equally impressive is the museum’s collection of Burgess Shale fossils, which preserve soft-bodied creatures from the Cambrian period in extraordinary detail, offering rare glimpses into the anatomical features of Earth’s earliest complex animals. Visitors marvel at the museum’s extensive collection of ammonites, which range from specimens smaller than a coin to examples larger than automobile tires, demonstrating the diversity within this extinct group of mollusks. The fossil collection also includes exquisitely preserved insects in amber, complete pterosaur skeletons with delicate wing membranes intact, and mammal fossils documenting the rapid diversification following the dinosaurs’ extinction. Each specimen is presented with context about its discovery, scientific significance, and the often colorful personalities who first brought these ancient creatures to scientific attention.

The Mineral Gallery: Earth’s Natural Treasures

Beyond its paleontological holdings, the Sedgwick Museum boasts an extensive mineral collection that showcases Earth’s inorganic wonders in all their crystalline glory. The mineral gallery dazzles visitors with specimens ranging from massive amethyst geodes that stand taller than a child to microscopic crystalline structures that require magnification to appreciate their geometric perfection. Organized according to chemical composition and crystal structure, the display demonstrates how minerals form under various conditions of temperature, pressure, and chemical environment throughout the planet. Particularly noteworthy are the museum’s examples of minerals first identified by British mineralogists, including specimens that served as the “type specimens” against which all other examples are compared. Interactive displays allow visitors to explore the physical properties that define minerals, such as hardness, luster, and cleavage patterns, while special lighting reveals the fluorescent properties of certain specimens that glow in vivid colors under ultraviolet light. The mineral collection also contextualizes human interaction with these resources, tracing the historical importance of mining in British culture and the ongoing relevance of mineral science to technologies ranging from smartphones to renewable energy systems.

Scientific Instruments: Tools of Discovery

The Sedgwick Museum preserves not only the discoveries of early geologists but also the actual tools they used to revolutionize our understanding of Earth’s history. Glass-fronted cabinets display delicate brass microscopes from the Victorian era that first revealed the microscopic structures of rocks and fossils, allowing scientists to classify materials with unprecedented precision. Visitors can examine Sedgwick’s own field hammers, worn smooth from decades of striking rocks in search of fossil evidence, alongside his meticulously maintained field notebooks filled with detailed sketches and observations. The collection includes early surveying equipment such as theodolites and clinometers that enabled geologists to map strata and understand the three-dimensional relationships between rock formations. Particularly fascinating are the early spectroscopes and chemical analysis kits that pioneered techniques for determining the composition of minerals, establishing the foundation for modern geochemistry. These instruments are not merely antiquated curiosities but represent crucial technological innovations that made possible the scientific advances documented throughout the museum, demonstrating how progress in earth sciences has always depended on the development of increasingly sophisticated observational tools.

The Great Debates: Controversies That Shaped Geology

The Sedgwick Museum serves as a physical record of the profound scientific controversies that ultimately defined geology as a modern discipline. Perhaps most famous is the Neptunist-Plutonist debate, represented through rock specimens collected by proponents of both theories, with Abraham Gottlob Werner arguing that all rocks precipitated from a primordial ocean and James Hutton countering that many rocks formed through volcanic processes. The museum documents the catastrophism versus uniformitarianism controversy through the collections and writings of Georges Cuvier and Charles Lyell respectively, showcasing how these competing views of Earth’s developmental processes fundamentally shaped geological thinking. Visitors can explore the contentious dating of the Earth through displays that trace how estimates expanded from Bishop Ussher’s biblical chronology of merely 6,000 years to the modern understanding of 4.5 billion years through advances in radiometric dating. The museum thoughtfully presents these controversies not as failures of science but as essential components of scientific progress, demonstrating how competing hypotheses, rigorous debate, and new evidence gradually refined our understanding of geological processes. Interactive displays encourage visitors to consider how scientists evaluate competing theories and the role that new technological capabilities play in resolving seemingly intractable scientific disputes.

The Cambridge School of Geology: Academic Impact

The Sedgwick Museum stands as the physical embodiment of the Cambridge School of Geology, an academic tradition that has influenced geological thinking worldwide for over two centuries. Beginning with Adam Sedgwick’s appointment as Woodwardian Professor in 1818, Cambridge established itself as a center for geological education that emphasized field observation, systematic collection, and the integration of multiple scientific disciplines. The museum documents how Cambridge geologists pioneered paleoecological approaches that considered ancient organisms within their environmental contexts rather than as isolated specimens. Through archival materials and personal collections, visitors can trace how the Cambridge tradition shaped the careers of influential geologists including Thomas McKenny Hughes, who expanded the museum’s collections throughout the British Empire, and William Whitehead Watts, whose textbooks trained generations of geology students around the world. The museum also highlights Cambridge’s continuing influence on modern geology through displays featuring the work of contemporary researchers using advanced techniques like isotope geochemistry and computer modeling to address questions first raised by their institutional predecessors. Educational programming emphasizes this continuity, with current Cambridge geology students leading tours that connect the historical collections to ongoing research projects at the university.

Educational Legacy: Teaching Through Objects

Since its inception, the Sedgwick Museum has maintained a dual identity as both research repository and educational institution, pioneering object-based learning approaches that continue to influence science education. Adam Sedgwick himself revolutionized geological instruction by insisting that students directly examine rock and fossil specimens rather than simply memorizing taxonomic categories or theoretical principles from books. This pedagogical philosophy manifests throughout the museum in dedicated teaching spaces where visitors can handle selected specimens under guidance from museum educators, experiencing the tactile qualities that distinguish different rock types or fossil structures. The museum maintains specially designed educational collections that travel to local schools, extending the institution’s reach beyond its physical walls and introducing thousands of students annually to geological concepts through direct observation. Digital initiatives now complement these traditional approaches, with high-resolution imaging technology allowing virtual examination of fragile specimens that cannot be handled. The museum’s educational staff continuously develops curriculum-linked resources that help teachers integrate the collections into broader science education, while university students in geology, biology, and environmental sciences still utilize the collections for laboratory exercises, maintaining a direct connection to Sedgwick’s original teaching methods.

Conservation Challenges: Preserving the Past for the Future

Maintaining the Sedgwick’s vast collection presents unique conservation challenges that balance preservation needs with research access and public education. Many specimens face natural deterioration processes, with pyrite-rich fossils particularly vulnerable to “pyrite disease,” a chemical reaction that can cause specimens to crumble into dust if not carefully controlled through specialized storage conditions with precise humidity levels. The museum employs conservators who use cutting-edge techniques including 3D scanning to document specimens in their current state, creating digital backups that preserve scientific data even if physical specimens deteriorate. Historical wood and glass display cases, while aesthetically valuable, present challenges for maintaining appropriate environmental conditions, requiring careful retrofitting with modern climate control systems hidden within the original structures. The conservation team constantly monitors light levels throughout the galleries, protecting light-sensitive specimens from fading while ensuring visibility for visitors. Perhaps most challenging is balancing access with preservation—researchers need to handle specimens directly, yet each instance of handling increases risk of damage. The museum addresses this through carefully documented handling protocols, creation of research-quality casts of particularly valuable specimens, and increasingly sophisticated imaging technologies that can reveal internal structures without physically sectioning irreplaceable fossils.

Global Connections: International Research and Collaboration

While rooted in Cambridge, the Sedgwick Museum maintains extensive international connections that reflect both its colonial history and its contemporary research relevance. The collection includes specimens from every continent, many gathered during the height of the British Empire when Cambridge-trained geologists accompanied colonial expeditions and sent materials back to their alma mater. Today, the museum acknowledges this complex legacy while fostering collaborative international research partnerships that emphasize mutual benefit and scientific exchange. The museum participates in major international digitization initiatives that make collection data available to researchers worldwide, democratizing access to specimens that were previously only available to those who could travel to Cambridge. Visiting researcher programs bring scientists from institutions around the world to work directly with the collections, while loan programs allow specimens to travel for special exhibitions or research projects at partner institutions. The museum actively collaborates with indigenous communities in areas where historical specimens were collected, developing protocols for respectful engagement and sometimes repatriation of culturally significant materials. These international connections ensure that the Sedgwick remains not just a repository of Cambridge’s geological history but a globally relevant research resource that contributes to our collective understanding of Earth’s development.

The Future of the Sedgwick: Embracing New Technologies

As the Sedgwick Museum approaches its third century, it embraces technological innovations that extend its reach and research capabilities while remaining true to its foundational mission. Advanced imaging technologies now allow researchers to examine the internal structures of fossils without damaging them, using techniques like micro-CT scanning that produces detailed three-dimensional models revealing features invisible to earlier generations of paleontologists. The museum has embarked on an ambitious digitization program, creating high-resolution images and 3D models of key specimens that are accessible through online databases, allowing virtual examination by researchers and enthusiasts worldwide. Augmented reality applications enhance the visitor experience, overlaying digital reconstructions of how ancient creatures appeared in life onto the fossilized remains displayed in cases. The museum employs social media and digital storytelling to connect with audiences beyond its physical walls, sharing collection highlights and research developments with global audiences. Despite these technological advances, the Sedgwick maintains its commitment to direct observation of actual specimens, viewing digital tools as supplements to rather than replacements for the irreplaceable experience of seeing authentic geological materials. This balanced approach positions the museum to remain relevant through changing technological landscapes while preserving the hands-on scientific tradition established by its namesake.

Conclusion

The Sedgwick Museum stands as a living monument to humanity’s enduring fascination with Earth’s deep history. More than simply a collection of rocks and fossils, it represents the accumulated knowledge of generations of scientists who dedicated their lives to understanding our planet’s development. From Adam Sedgwick’s pioneering fieldwork to today’s cutting-edge research techniques, the museum documents not just what we know about Earth’s past but how we came to know it. As visitors walk through its historic galleries, they participate in this ongoing journey of discovery, connecting with both the ancient creatures preserved in stone and the human minds that brought them back into our collective consciousness. In a rapidly changing world where scientific literacy becomes increasingly crucial, the Sedgwick Museum continues its centuries-old mission of education and inspiration, helping us comprehend the immense timescales and profound changes that shaped the world we inhabit today.