When most people think about dinosaur remains, they picture the massive skeletons displayed in museums – those awe-inspiring bone structures that seem to defy time itself. But here’s something that might blow your mind: not all “dinosaur bones” you see are actually bones at all. Some of the most famous dinosaur specimens in the world are elaborate stone replicas of what once lived and breathed millions of years ago. The line between genuine bone and fossilized rock is far more blurred than most people realize, and the truth behind what we’re really looking at when we stare up at a T-Rex skeleton is absolutely fascinating.

The Shocking Truth About Museum Displays

Walk into any major natural history museum, and you’ll be greeted by towering dinosaur skeletons that seem to transport you back 65 million years. However, many visitors would be stunned to learn that a significant portion of what they’re admiring isn’t original bone material at all. Most museum displays are actually a combination of real fossils, plaster casts, and modern reconstructions.

The famous “Sue” the T-Rex at the Field Museum in Chicago, for instance, has her original skull safely stored away from public view due to its incredible weight and fragility. What visitors see mounted on the skeleton is a lightweight cast. This practice is so common that paleontologists estimate that complete dinosaur skeletons displayed in museums often contain less than 50% original fossil material.

What Actually Happens During Fossilization

The fossilization process is like nature’s most incredible magic trick, but it takes millions of years to complete. When a dinosaur died, its bones had to be buried quickly under layers of sediment to avoid decomposition and scavenging. Over time, mineral-rich groundwater seeped through the sediment layers, gradually replacing the organic material in the bones with minerals like silica, calcite, or pyrite.

This process, called permineralization, essentially turns the original bone into stone while preserving its shape and internal structure down to microscopic details. The original calcium phosphate that made up the bone is completely replaced, meaning what we call a “fossil” is technically a rock sculpture of the original bone. It’s like having a perfect 3D photocopy made of stone instead of the original document.

The entire process requires incredibly specific conditions – the right temperature, pH levels, and mineral content in the surrounding environment. Scientists estimate that only about one in a million organisms that ever lived became fossilized, making each discovery extraordinarily precious.

The Rare Cases of Actual Preserved Bone

While true fossilization replaces organic material with minerals, there are exceptional cases where actual dinosaur bone material has survived. These instances are incredibly rare and occur under very specific preservation conditions. Some dinosaur remains found in permafrost, amber, or extremely dry environments have retained small amounts of original organic compounds.

In 2005, paleontologist Mary Schweitzer made headlines when she discovered what appeared to be soft tissue, including blood vessels and proteins, inside a T-Rex femur that was 68 million years old. This discovery challenged everything scientists thought they knew about preservation limits. While the finding remains controversial, it opened up possibilities that some original biological material might persist far longer than previously believed.

Unfossilized Bones: The Living Dinosaur Connection

Here’s where things get really interesting: birds are literally living dinosaurs, direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs like Velociraptor and T-Rex. Every chicken bone, eagle talon, and hummingbird skeleton represents unfossilized dinosaur bone material that’s very much alive today. When you hold a bird bone, you’re essentially holding a modern dinosaur bone.

This connection isn’t just poetic – it’s scientifically accurate. Birds evolved from small theropod dinosaurs during the Jurassic period, and they’ve retained many of the same bone structures and characteristics. The hollow bones that make flight possible in modern birds were actually first developed by their dinosaur ancestors. So in a very real sense, unfossilized dinosaur bones are all around us, walking, flying, and singing in our backyards.

Trace Fossils: When Bones Aren’t the Story

Not all dinosaur evidence comes in the form of bones at all. Trace fossils – including footprints, coprolites (fossilized poop), skin impressions, and even dinosaur vomit – provide incredible insights into dinosaur behavior and biology without preserving a single bone. These traces often reveal more about how dinosaurs lived than their skeletal remains ever could.

The famous dinosaur trackways found in places like Glen Rose, Texas, show entire herds of dinosaurs moving together, providing evidence of social behavior that bones alone could never reveal. Some of these trace fossils are so well-preserved that scientists can determine the speed at which individual dinosaurs were moving, whether they were limping from injuries, and even their approximate body weight.

What makes trace fossils particularly fascinating is that they capture moments in time – a split second when a dinosaur stepped in mud or left behind evidence of its daily activities. Unlike bones, which only tell us about death and burial, trace fossils give us glimpses into the actual lives of these ancient creatures.

The Chemistry of Fake vs. Real

Distinguishing between original bone material and fossilized rock requires sophisticated chemical analysis that goes far beyond what the naked eye can detect. Original bone contains specific proteins like collagen, as well as particular isotope signatures that differ from the surrounding rock matrix. When paleontologists want to determine if they’re dealing with original bone material, they often use techniques like mass spectrometry and X-ray crystallography.

The process is similar to forensic investigation – scientists look for chemical fingerprints that can only come from living organisms. Organic compounds break down in predictable ways, so finding certain amino acids or protein fragments can indicate whether any original biological material remains. However, contamination from the surrounding environment can make these determinations extremely challenging.

Mummified Dinosaurs: The Ultimate Preservation

In extremely rare cases, dinosaur remains have been found in such exceptional preservation states that they’re essentially mummified rather than fossilized. These specimens, sometimes called “dinosaur mummies,” retain skin, muscle tissue, and even stomach contents in remarkable detail. The preservation is so complete that scientists can study the actual texture of dinosaur skin and the contents of their last meals.

One of the most famous examples is “Dakota,” a Hadrosaur found in North Dakota that was so well-preserved that scientists could determine the exact pattern of its skin and even estimate its muscle mass. The specimen was preserved in a way that natural desiccation occurred rapidly, essentially freeze-drying the carcass before decomposition could set in. These finds are incredibly rare, with only a handful of such specimens discovered worldwide.

The Age Factor: How Time Changes Everything

The age of dinosaur remains plays a crucial role in determining whether any original bone material might still exist. Dinosaurs from the Mesozoic Era (roughly 65-250 million years ago) have had vastly more time for complete fossilization compared to more recent prehistoric animals. The older the specimen, the more likely it is that every trace of original organic material has been replaced by minerals.

However, some dinosaur fossils from the very end of the Cretaceous period, particularly those found in exceptional preservation sites like Hell Creek Formation, occasionally yield surprises. The relatively “young” age of these specimens – only 66 million years old – combined with specific burial conditions, means that microscopic traces of original material might occasionally survive. This creates a fascinating gray area where the line between fossil and bone becomes increasingly blurred.

Modern Technology Reveals Ancient Secrets

Advanced imaging techniques are revolutionizing how scientists examine dinosaur remains and determine what’s original versus fossilized. Synchrotron radiation, high-resolution CT scanning, and electron microscopy can reveal cellular structures and chemical compositions at the molecular level. These technologies have revealed that some “fossils” contain far more original material than previously thought possible.

Recent discoveries using these techniques have found preserved melanosomes (color-bearing structures) in dinosaur feathers, allowing scientists to determine the actual colors of some dinosaur species. This represents a bridge between original biological material and fossilized remains – the structures are still there, just mineralized over millions of years. It’s like finding the original paint on a house that’s been completely rebuilt with new materials.

The Controversial Soft Tissue Discoveries

Mary Schweitzer’s discovery of apparent soft tissue in T-Rex bones sparked one of the most heated debates in paleontology. The implications were staggering – if organic material could survive for 68 million years, it would completely rewrite our understanding of preservation limits. Some scientists argued that what appeared to be soft tissue was actually biofilm or other contamination that had formed long after the dinosaur’s death.

The controversy intensified when similar findings were reported in other dinosaur specimens, including blood vessels, proteins, and even what appeared to be red blood cells. While the scientific community remains divided on the interpretation of these findings, they’ve opened up entirely new avenues of research. If even a fraction of these discoveries represent original biological material, it would mean that some dinosaur “fossils” are actually partially preserved specimens rather than complete mineral replacements.

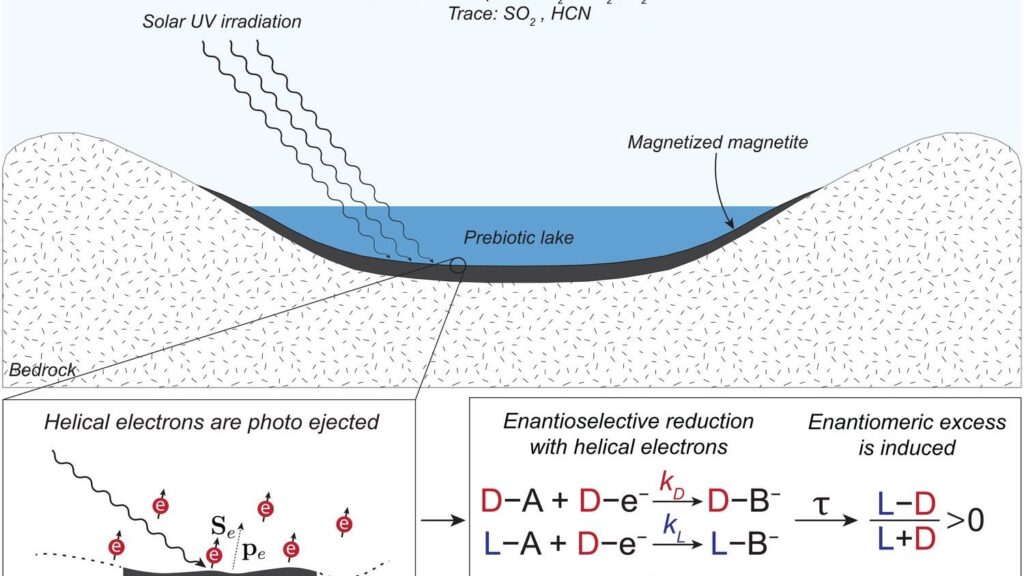

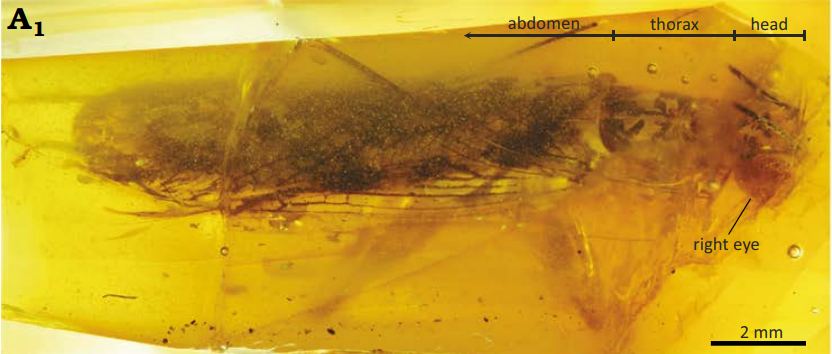

Amber: Nature’s Time Capsule

While complete dinosaur skeletons have never been found preserved in amber, numerous dinosaur-era specimens have been discovered trapped in this fossilized tree resin. These amber specimens preserve original organic material with stunning clarity, including dinosaur feathers, skin, and even blood-filled ticks that may have fed on dinosaurs. The preservation in amber is so complete that DNA extraction has been attempted, though without success so far.

The amber specimens represent a unique category – they’re not fossils in the traditional sense because the organic material hasn’t been replaced by minerals. Instead, they’re original biological specimens that have been naturally embalmed for over 100 million years. These finds provide an incredible window into the diversity and appearance of dinosaur-era life, preserving details that would be impossible to detect in conventional fossils.

Ice Age Overlaps: The Blurred Timeline

While non-avian dinosaurs went extinct 66 million years ago, the discovery of well-preserved ice age mammals has created interesting parallels in preservation science. Mammoths, saber-toothed cats, and other ice age creatures found in permafrost often retain significant amounts of original organic material, including DNA. This raises fascinating questions about whether similar preservation might be possible for very late-surviving dinosaur populations.

Some scientists speculate that if small populations of dinosaurs had survived into colder periods or reached extreme latitudes, they might have been preserved in ways similar to ice age mammals. While no such discoveries have been made, the theoretical possibility highlights how environmental conditions can dramatically affect what survives through geological time. The boundary between “fossil” and “preserved specimen” becomes much more fluid when considering these extreme preservation scenarios.

The Future of Dinosaur Bone Authentication

As technology advances, the methods for distinguishing between original bone material and fossilized rock are becoming increasingly sophisticated. New techniques using laser ablation, isotope analysis, and even quantum dating methods are pushing the boundaries of what scientists can detect in ancient specimens. These advances may eventually allow researchers to identify original biological material at the molecular level, even in specimens that appear completely fossilized.

The implications are profound – if scientists can reliably identify original dinosaur proteins or genetic material, it could revolutionize our understanding of evolution, extinction, and even the possibility of de-extinction technologies. However, these same advances also highlight how much we still don’t know about the preservation process and the true nature of what we call “dinosaur fossils.”

Why This Distinction Matters

Understanding the difference between original bone and fossilized rock isn’t just academic curiosity – it has real implications for how we study prehistoric life and understand the limits of preservation. If some dinosaur specimens contain original biological material, they represent an unprecedented resource for studying extinct organisms at the molecular level. This could provide insights into dinosaur physiology, behavior, and evolution that traditional fossil analysis could never reveal.

The distinction also matters for museum education and public understanding of paleontology. When visitors marvel at dinosaur skeletons, they deserve to know whether they’re looking at the actual remains of ancient creatures or skillfully crafted stone replicas. This knowledge doesn’t diminish the wonder of these discoveries – if anything, understanding the incredible process of fossilization makes these specimens even more remarkable.

The question of whether dinosaur bones exist that aren’t technically fossils opens up a world of scientific possibility and wonder that challenges our basic assumptions about time, preservation, and the nature of life itself. As we continue to push the boundaries of what’s possible in paleontological research, the line between fossil and bone may become even more intriguingly blurred. What discoveries await us in the next decade of dinosaur research?