Picture this: it’s 250 million years ago, and Earth is recovering from the greatest extinction event in its history. The planet is a laboratory of evolutionary experimentation, where nature throws caution to the wind and creates some of the most bizarre, magnificent, and downright weird creatures ever to walk, swim, or fly. Welcome to the Triassic Period, a time when life didn’t just bounce back—it went absolutely wild with creativity. This wasn’t just recovery; this was nature’s renaissance, a period of unprecedented biological innovation that would make even today’s most imaginative science fiction writers jealous.

The Great Comeback: When Life Got Creative

The Triassic Period began with a world in shambles. The Permian-Triassic extinction had wiped out roughly 90% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrates. But here’s where it gets fascinating—nature abhors a vacuum, and boy did it fill this one spectacularly.

Empty ecological niches became playgrounds for evolutionary experimentation. Without the dominant groups that had ruled before, life could explore entirely new body plans and lifestyles. It’s like clearing out a crowded restaurant and watching completely different types of people discover they can now sit wherever they want.

The result? A parade of creatures so strange they seem designed by a committee of mad scientists. From tiny gliding reptiles to massive marine predators with heads full of teeth, the Triassic was evolution’s sketch pad.

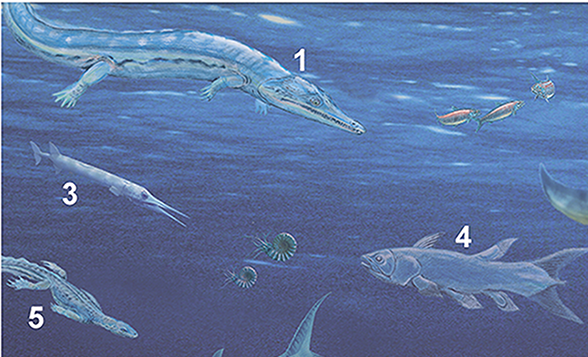

Tanystropheus: The Giraffe of the Ancient Seas

Imagine a creature that looks like someone took a normal reptile and stretched its neck through a medieval torture device. Meet Tanystropheus, arguably one of the most bizarre-looking animals ever discovered. This 20-foot-long reptile had a neck that made up more than half its total body length—we’re talking about a neck longer than a school bus.

Scientists initially thought they were looking at two different animals when they first found Tanystropheus fossils. The neck was so disproportionate that it seemed impossible for one creature to possess such an extreme body plan. Yet here it was, defying every rule of what we thought was anatomically possible.

This aquatic oddball used its impossibly long neck like a fishing rod, keeping its body hidden while its tiny head darted through the water catching fish and squid. Think of it as nature’s first experiment in remote-controlled hunting.

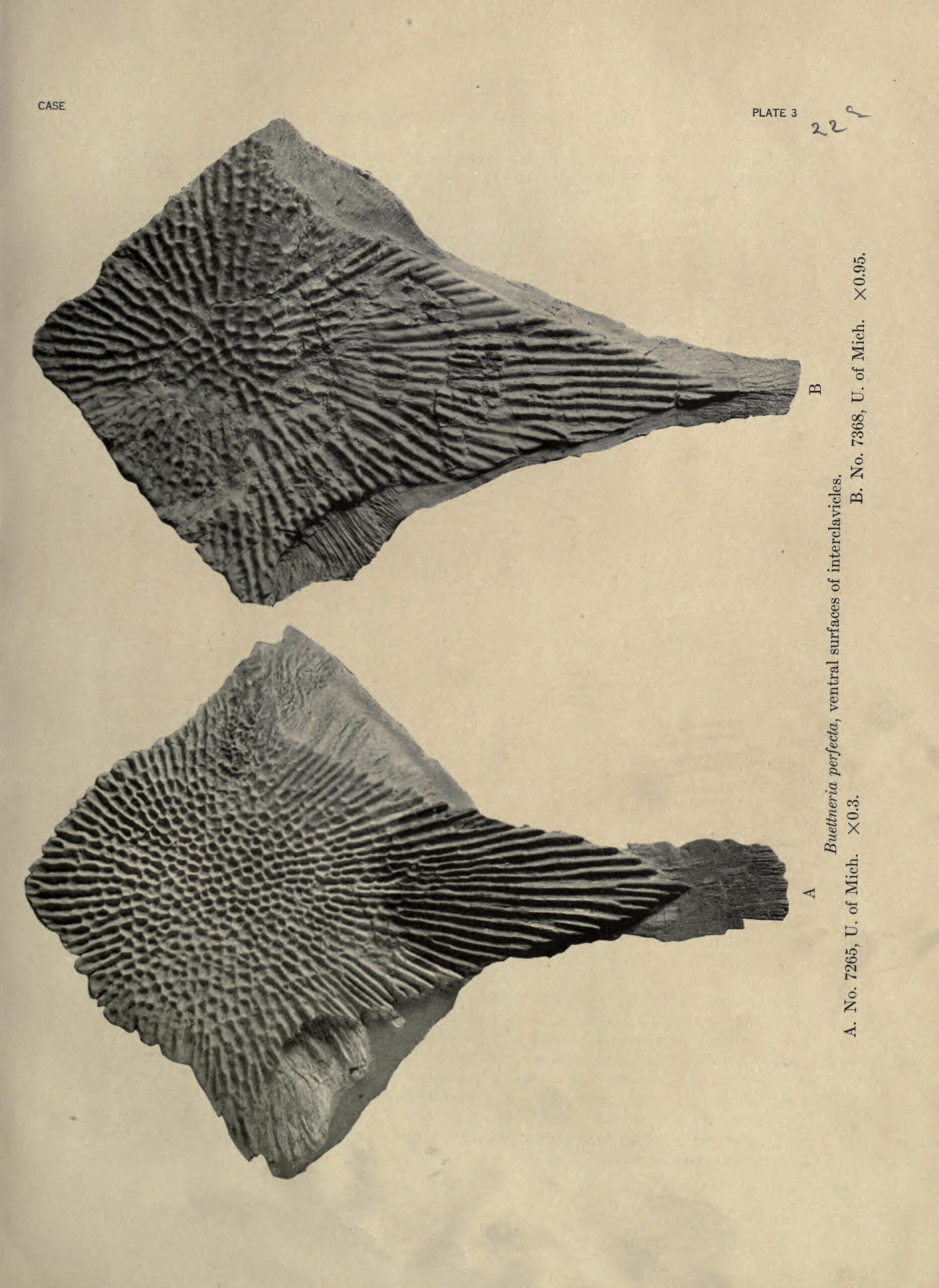

Henodus: The Turtle That Wasn’t Quite a Turtle

Before modern turtles perfected their shell game, there was Henodus—a creature that looked like nature’s rough draft. This bizarre marine reptile had a shell, sure, but it was more like wearing a suit of armor made from bathroom tiles. The shell was composed of hundreds of small, hexagonal plates that created a mosaic pattern across its back.

What made Henodus truly odd was its lifestyle. Unlike modern turtles that can retreat into their shells, Henodus was stuck with its head and limbs permanently exposed. It was essentially a walking (or swimming) contradiction—armored yet vulnerable.

This peculiar turtle-like creature spent its days filter-feeding in shallow lagoons, using its beak-like mouth to strain small organisms from the water. It was like having a living, breathing garbage disposal with a designer shell.

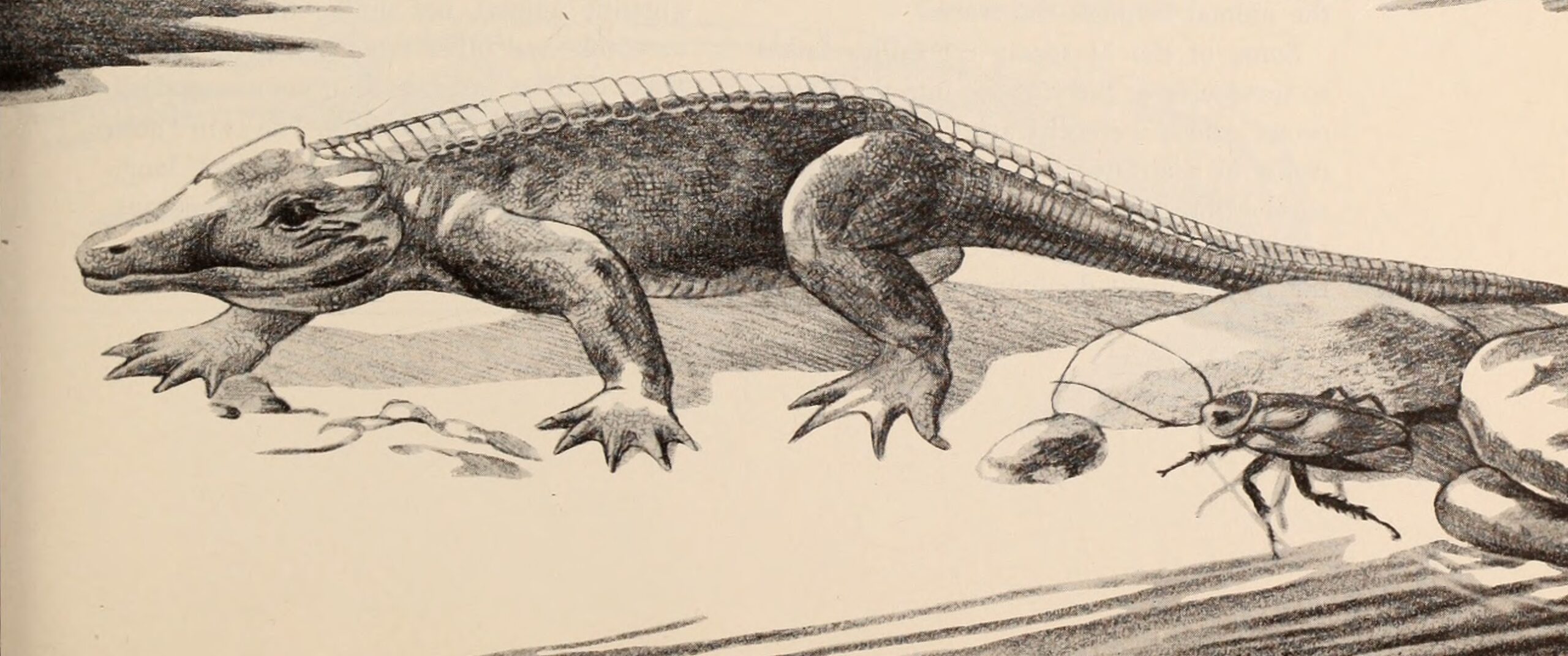

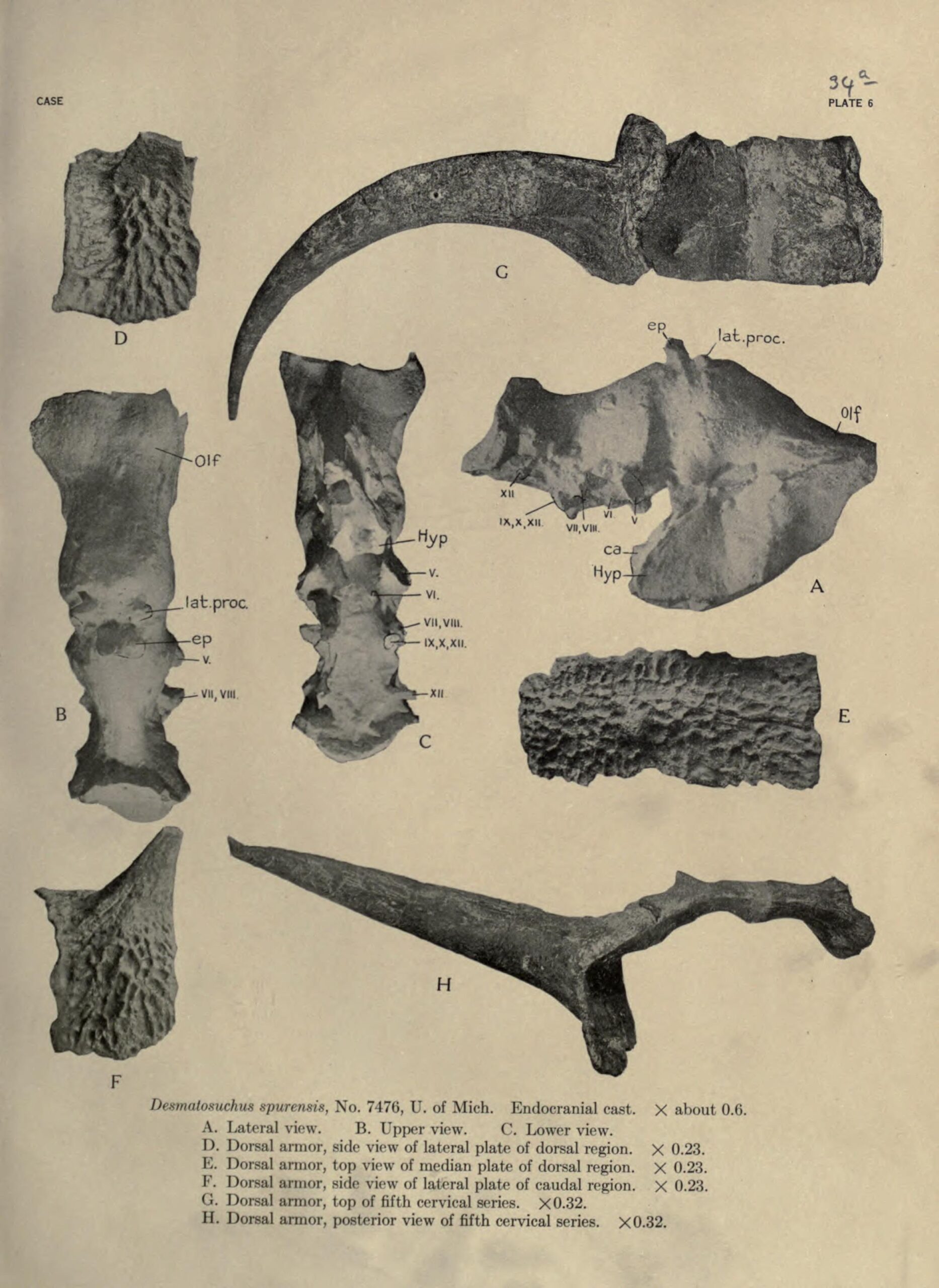

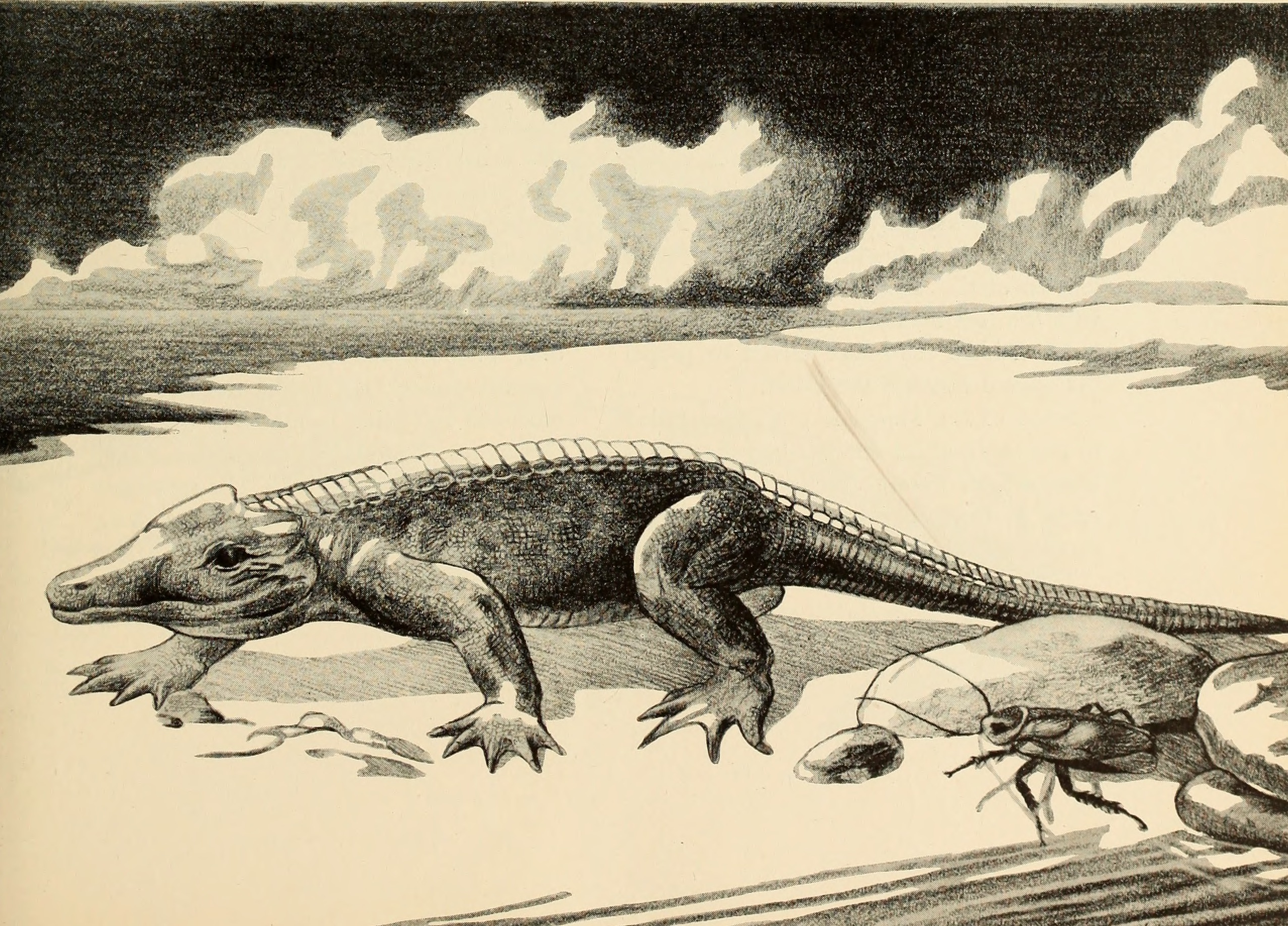

Desmatosuchus: The Crocodile in Knight’s Armor

Picture a crocodile that decided to cosplay as a medieval knight, and you’ve got Desmatosuchus. This 16-foot-long archosaur was covered head to tail in heavy armor plating, with rows of protective osteoderms running down its back and sides like a spinal highway of bone.

But here’s the kicker—despite looking like it could chomp through a small car, Desmatosuchus was actually a vegetarian. Its pig-like snout was perfectly designed for rooting through soil and vegetation, not for the bone-crushing lifestyle its appearance suggested.

This armored herbivore roamed the Late Triassic landscape like a living tank, probably feeling pretty confident about its defensive capabilities. It’s nature’s reminder that sometimes the most intimidating-looking creatures are actually the gentlest souls.

Sharovipteryx: The Backwards Flying Experiment

Flying has been invented multiple times throughout Earth’s history, but Sharovipteryx might have the strangest approach to getting airborne. This tiny reptile, about the size of a sparrow, had wings attached to its hind legs rather than its arms—imagine a bat flying backwards and you’re on the right track.

This peculiar little glider had enormous hind limbs with flight membranes stretching between them, while its front limbs remained relatively normal. It’s like evolution was experimenting with different wing configurations and thought, “What if we tried putting them on the back legs this time?”

Scientists still debate whether Sharovipteryx could actually fly or just glide, but one thing’s certain—it represents one of the most unusual approaches to aerial locomotion ever discovered. It’s nature’s reminder that there’s often more than one way to solve a problem.

Atopodentatus: The Vacuum Cleaner of Ancient Seas

If you thought modern animals had weird feeding strategies, wait until you meet Atopodentatus. This marine reptile had a mouth that looked like it was designed by someone who’d never seen a normal animal before. Its upper jaw was split down the middle, creating a bizarre zipper-like arrangement that could expand sideways.

This strange mouth configuration allowed Atopodentatus to function like a living vacuum cleaner, scraping algae and small organisms off rocks and coral reefs. It would position its split upper jaw against a surface and use its hundreds of tiny teeth to harvest food like a prehistoric lawn mower.

The discovery of Atopodentatus revolutionized our understanding of marine ecosystems during the Triassic. It showed that even in the aftermath of mass extinction, life found incredibly specialized ways to exploit available resources.

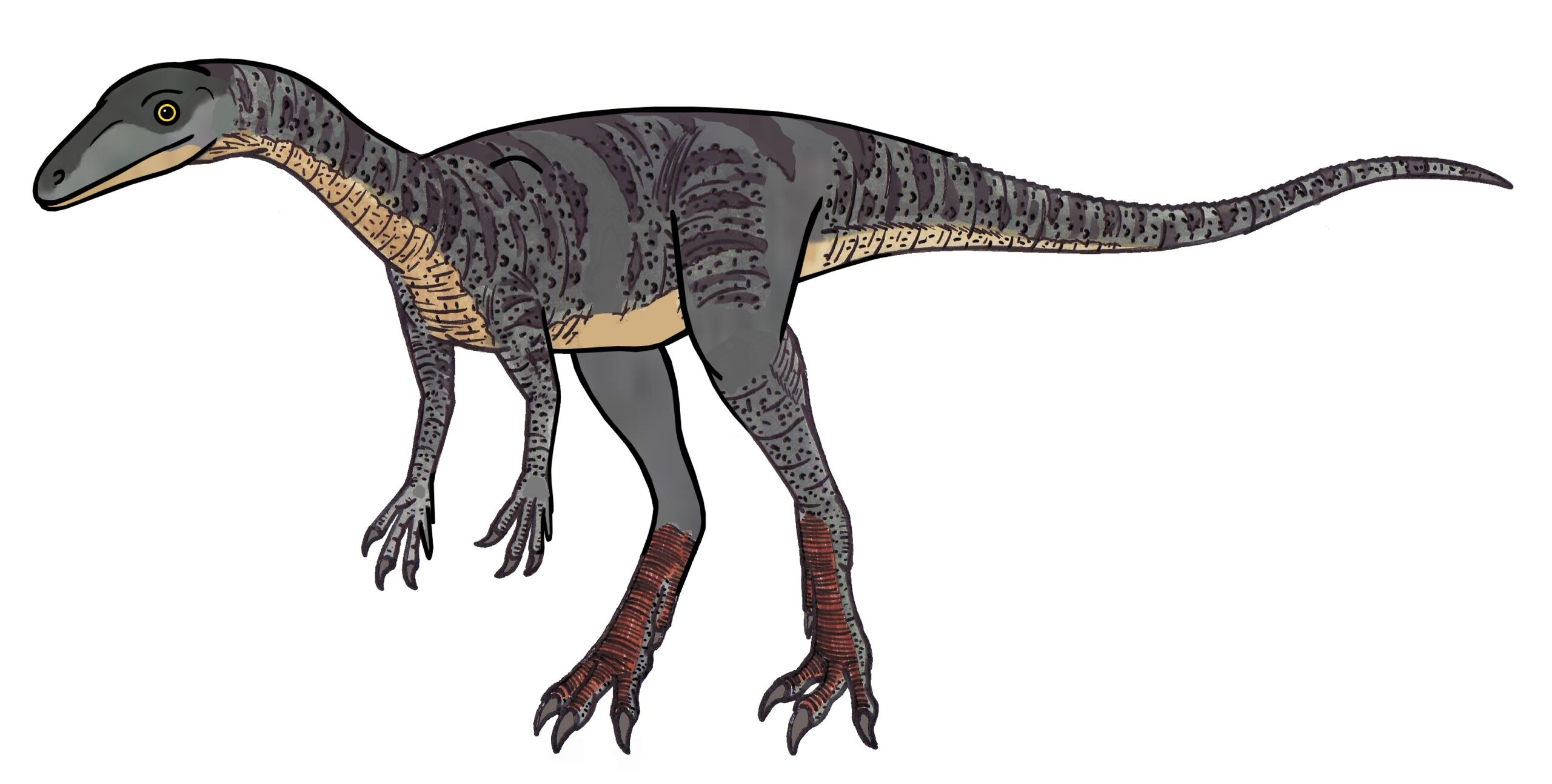

Effigia: The Crocodile That Dreamed of Being an Ostrich

Convergent evolution is when unrelated animals develop similar traits, and Effigia is perhaps the most striking example from the Triassic. This crocodile relative looked so much like a modern ostrich that it’s almost comical—long neck, long legs, and a body built for running rather than lurking in swamps.

Effigia stood about 10 feet tall and could probably outrun most of its contemporaries. Its long, powerful legs were built for speed, not for the semi-aquatic lifestyle we associate with modern crocodilians. It’s like nature was beta-testing the ostrich design 200 million years before birds perfected it.

This remarkable example of convergent evolution shows how similar environmental pressures can produce remarkably similar solutions, even in completely unrelated lineages. Sometimes the best ideas are worth repeating.

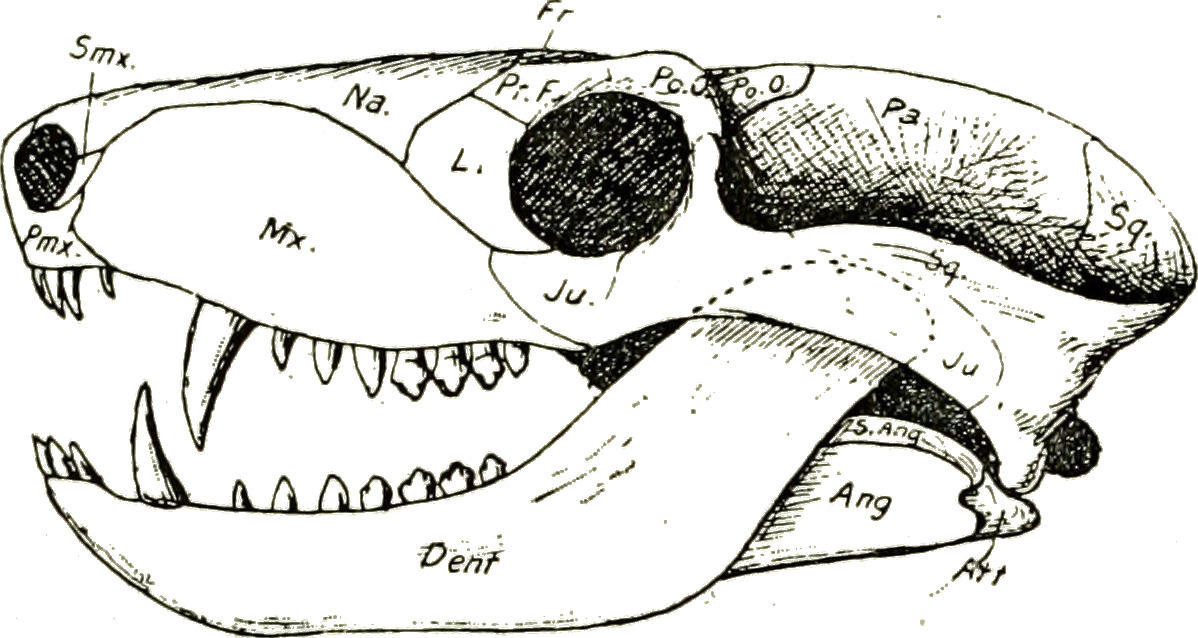

Placodus: The Walrus-Toothed Sea Cow

Imagine a hippopotamus that decided to become a professional oyster shucker, and you’ve got a pretty good mental image of Placodus. This chunky marine reptile had massive, protruding front teeth that made it look like a prehistoric walrus, but it used these impressive chompers for a very different purpose.

Placodus was a mollusk specialist, using its powerful jaws and flat back teeth to crack open shellfish like nature’s own nutcracker. Its front teeth weren’t for fighting or display—they were precision tools for prying shellfish off rocks in shallow coastal waters.

This stocky swimmer represents one of the earliest experiments in specialized marine feeding strategies. It’s a reminder that even the most unusual-looking adaptations usually serve a very practical purpose.

Longisquama: The Feathered Enigma

Long before birds took to the skies, there was Longisquama—a small reptile that might have been wearing nature’s first attempt at feathers. This cat-sized creature had a row of long, plume-like structures running down its back that looked remarkably similar to modern bird feathers.

The exact nature of these structures remains hotly debated among paleontologists. Were they proto-feathers? Modified scales? Or something else entirely? What we do know is that Longisquama was experimenting with external structures that wouldn’t become common until much later in evolutionary history.

This enigmatic little reptile challenges our understanding of when and how feathers first evolved. It’s like finding a rough draft of an invention that wouldn’t be perfected for millions of years.

Gerrothorax: The Flat-Faced Amphibian

If you took a modern salamander and ran it over with a steamroller, you might get something like Gerrothorax. This bizarre amphibian was flatter than a pancake, with eyes positioned on top of its head like a living doormat with attitude.

Gerrothorax spent its entire life in water, which was unusual for amphibians of its time. Its extremely flattened body plan was perfect for hiding on the bottom of lakes and rivers, waiting for unwary prey to swim overhead. It was essentially a living bear trap with fins.

This peculiar predator retained its gills throughout its adult life, making it one of the few vertebrates to completely abandon the terrestrial lifestyle that most amphibians pursue. Sometimes evolution decides that if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

Drepanosaurus: The Monkey-Lizard Hybrid

Picture a chameleon that decided to become a monkey, and you’ve got Drepanosaurus. This arboreal reptile had grasping hands, a prehensile tail, and a bird-like beak, creating one of the most unusual combinations of features ever seen in a single animal.

What made Drepanosaurus truly special was its massive claw on each hand—not for hunting, but for hanging from branches and stripping bark to get at insects underneath. It was like having a built-in Swiss Army knife attached to each arm.

This tree-dwelling oddball shows that even in the Triassic, some animals were already experimenting with the arboreal lifestyle that would later be perfected by primates. It’s evolution’s early attempt at creating the ultimate tree-climbing machine.

Vancleavea: The Armored Swimmer

Vancleavea looked like someone took a crocodile and decided to armor-plate it while adding extra-long legs for good measure. This semi-aquatic reptile was covered in bony plates and had disproportionately long limbs that made it look like it was wearing stilts.

Despite its bizarre appearance, Vancleavea was perfectly adapted for life in and around water. Its long legs allowed it to wade through shallow areas while its armor protected it from predators. It was like having a mobile fortress that could double as a fishing platform.

This unusual archosaur represents another example of the Triassic’s experimental approach to body design. Why settle for conventional when you can be spectacularly weird?

Paraplacodus: The Transitional Sea Serpent

Paraplacodus represents evolution caught in the act of creating marine reptiles. This early member of the plesiosaur lineage still had legs suitable for walking on land, but its body was already adapting to aquatic life.

What makes Paraplacodus fascinating is that it shows us the transitional stage between terrestrial and fully aquatic lifestyles. It’s like having a snapshot of evolution’s work in progress, complete with all the awkward in-between stages.

This semi-aquatic reptile probably spent its time in coastal waters, using its still-functional legs to haul out onto beaches when necessary. It was nature’s rough draft for what would eventually become the magnificent marine reptiles of later periods.

Kuehneosaurus: The Original Gliding Reptile

Before there were flying squirrels, there was Kuehneosaurus—a small reptile that developed its own unique approach to gliding. This lizard-like creature had elongated ribs that supported gliding membranes, allowing it to soar from tree to tree like a prehistoric hang glider.

Kuehneosaurus was probably about the size of a modern iguana, but its gliding capabilities would have made it seem much larger when silhouetted against the sky. Its ability to glide would have been a tremendous advantage for escaping predators and accessing new food sources.

This early glider represents one of the first successful experiments in powered flight by vertebrates. It’s a reminder that the dream of flight is ancient, and life has been working on solving the problem for hundreds of millions of years.

The Legacy of Triassic Innovation

The Triassic Period’s bizarre menagerie teaches us something profound about life’s resilience and creativity. These weren’t just random mutations stumbling around in the dark—they were successful experiments that thrived in their respective environments, some for millions of years.

Many of these “failed” experiments actually contributed genetic and anatomical innovations that would later be refined by more familiar groups. The Triassic was essentially life’s research and development phase, testing ideas that would later become mainstream.

What’s truly remarkable is how these creatures pushed the boundaries of what we consider possible in animal design. They remind us that evolution is not a straight line toward perfection, but a wild, creative process that sometimes produces solutions we never could have imagined.

These ancient oddballs prove that our modern world, strange as it might seem, is actually quite conservative compared to the experimental wonderland of the Triassic. They challenge us to look at our current ecosystems with fresh eyes and wonder what new experiments nature might be cooking up right now. After all, today’s weirdest creatures might just be tomorrow’s evolutionary success stories—wouldn’t that be something to witness?