Picture this: 250 million years ago, Earth was a vastly different planet. The continents were still fused together into a supercontinent called Pangaea, and the climate was hot and dry across most of the land. But here’s the shocking part—dinosaurs hadn’t taken over yet. Instead, bizarre creatures that looked like crocodiles with mammal-like features dominated the landscape, alongside early archosaurs that resembled armored tanks more than the sleek predators we know today.

The rise of dinosaurs wasn’t just about evolution creating new species. It was a dramatic replacement story, where entire groups of animals were swept aside to make room for what would become the most successful land vertebrates in Earth’s history. This wasn’t a peaceful transition—it was nature’s equivalent of a corporate takeover, complete with mass extinctions, climate upheavals, and fierce competition for survival.

The Ruling Reptiles Before Dinosaurs

Before dinosaurs claimed their throne, the Permian period belonged to an entirely different cast of characters. The synapsids, often called “mammal-like reptiles,” were the true rulers of the ancient world. These weren’t your typical cold-blooded reptiles—many had hair-like structures, complex teeth, and some even showed signs of being warm-blooded.

The most impressive of these ancient rulers were creatures like Inostrancevia, a saber-toothed predator the size of a grizzly bear that could tear through bone with ease. Meanwhile, massive herbivores like Ulemosaurus, weighing up to 2 tons, lumbered across the landscape like prehistoric bulldozers. These animals had been perfecting their survival strategies for millions of years, seemingly unstoppable in their dominance.

But nature had other plans. The late Permian world was about to experience the most catastrophic mass extinction in Earth’s history, setting the stage for a complete reshuffling of life on our planet.

The Great Dying Sets the Stage

Around 252 million years ago, the Permian-Triassic extinction event—known ominously as “The Great Dying”—wiped out an estimated 96% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrates. This wasn’t just any extinction; it was the closest life on Earth has ever come to complete annihilation. Massive volcanic eruptions in what is now Siberia pumped toxic gases into the atmosphere, creating a runaway greenhouse effect that turned the planet into a hellscape.

The once-dominant synapsids were hit hardest by this catastrophe. Their complex metabolisms and specialized lifestyles made them particularly vulnerable to the rapid environmental changes. Ocean acidification, temperature spikes, and the collapse of food webs created a perfect storm that devastated their populations.

This mass extinction created an ecological vacuum that would soon be filled by entirely new groups of animals. The survivors of this apocalyptic event would inherit a world drastically different from the one their ancestors had known, and the stage was set for the rise of the archosaurs—the group that would eventually give birth to dinosaurs.

Enter the Archosaurs: The New Contenders

As the dust settled from the Great Dying, a new group of reptiles began to emerge from the shadows. The archosaurs, meaning “ruling reptiles,” were initially modest creatures that had survived the extinction in small numbers. However, they possessed several key advantages that would prove crucial in the post-extinction world.

Unlike their synapsid predecessors, archosaurs had more efficient respiratory systems, featuring air sacs that allowed for better oxygen circulation—a huge advantage in the oxygen-poor atmosphere of the early Triassic. They also had more flexible hip structures and stronger limb bones, making them better adapted for the new environmental conditions.

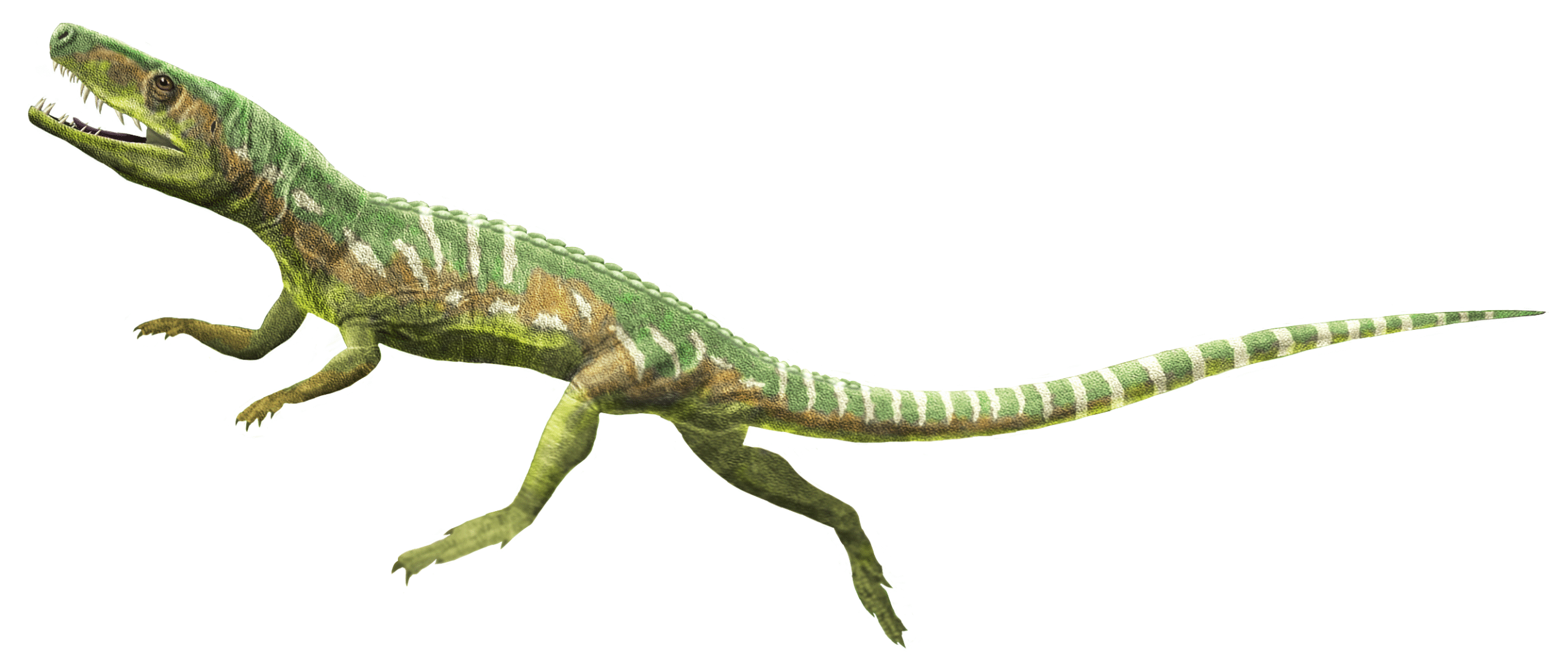

Early archosaurs like Euparkeria, about the size of a small dog, might not have looked like much, but they carried the genetic blueprint for what would become the most successful vertebrate lineage in history. These scrappy survivors were about to undergo one of the most remarkable evolutionary radiations ever recorded.

The Triassic Takeover Begins

Uploaded by FunkMonk, Public domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=25181948)

The early Triassic period was like a biological arms race in fast-forward. As ecosystems began to recover from the Great Dying, archosaurs rapidly diversified into numerous ecological niches. Some became aquatic predators, others evolved into heavily armored herbivores, and a few began experimenting with bipedal locomotion.

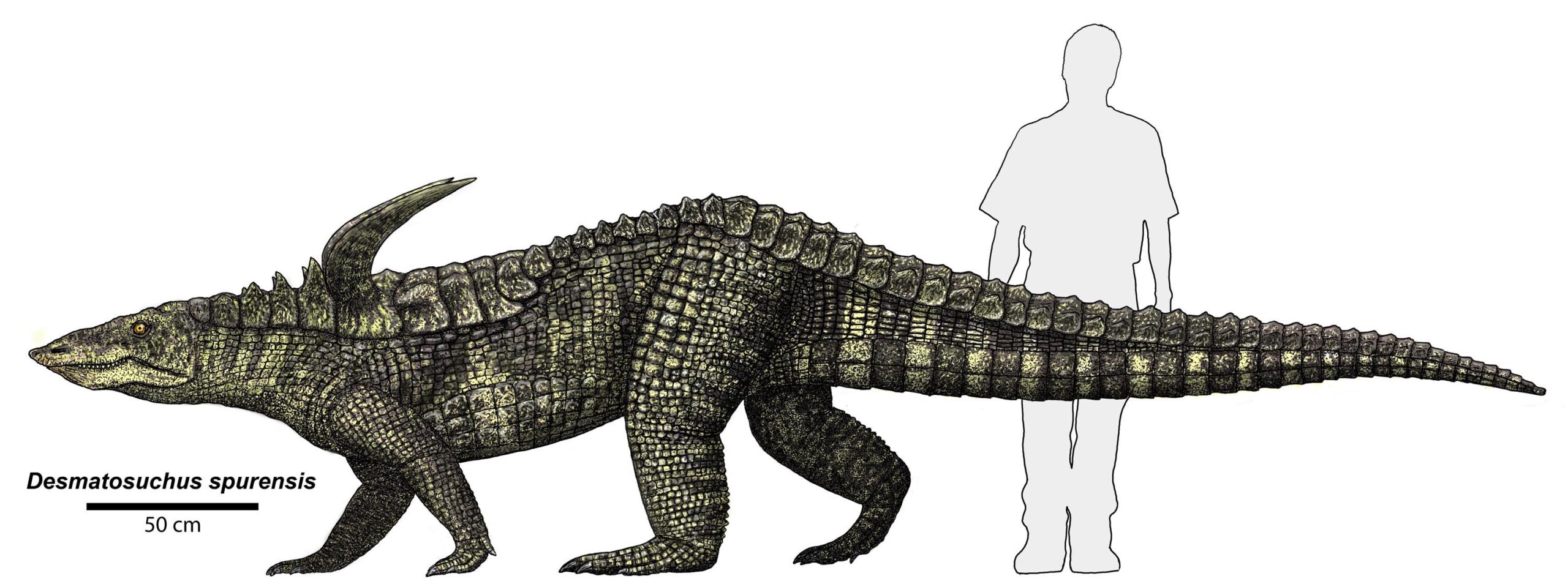

One of the most significant developments was the evolution of the crurotarsans, archosaurs that looked remarkably similar to modern crocodiles but filled roles we’d never expect today. Desmatosuchus, for instance, was a 16-foot-long herbivore covered in bony armor that resembled a walking fortress. Meanwhile, Postosuchus stood upright on its hind legs like a dinosaur, reaching lengths of 15 feet and terrorizing the landscape as an apex predator.

But perhaps the most important evolutionary experiment was happening in a small group of archosaurs that were developing longer legs, more upright postures, and increasingly bird-like characteristics. These were the early dinosauromorphs, and they were about to change everything.

The First Dinosaurs Emerge

Around 230 million years ago, deep in the forests of ancient Argentina, something extraordinary was taking shape. The first true dinosaurs, creatures like Eoraptor and Herrerasaurus, were stepping onto the evolutionary stage. These early dinosaurs were relatively small—most were no bigger than a large dog—but they possessed revolutionary adaptations that would eventually lead to global dominance.

What made these early dinosaurs special wasn’t their size or their fearsome appearance, but their biomechanics. They had evolved a unique hip structure that allowed their legs to move directly beneath their bodies, rather than sprawling out to the sides like most reptiles. This seemingly small change was actually a game-changer, providing much more efficient locomotion and endurance.

Additionally, many early dinosaurs had hollow bones filled with air sacs, making them lighter and more agile than their competitors. Some, like Coelophysis, traveled in large groups, suggesting complex social behaviors that gave them advantages in both hunting and defense.

Competition with Crurotarsans

The rise of dinosaurs wasn’t inevitable or immediate. For nearly 20 million years during the middle and late Triassic, dinosaurs had to compete directly with their crocodile-like cousins, the crurotarsans. This competition was intense, with both groups evolving similar solutions to environmental challenges.

Crurotarsans had several advantages over early dinosaurs. They were generally larger, more heavily armored, and had already established themselves in many ecological niches. Creatures like Saurosuchus, a 23-foot-long predator, dwarfed most early dinosaurs and seemed to have the upper hand in direct competition.

However, dinosaurs were developing their own secret weapons. Their more efficient respiratory systems, faster metabolisms, and superior locomotion were slowly giving them an edge in the evolutionary arms race. The question was whether these advantages would be enough to overcome the established dominance of the crurotarsans.

The Triassic-Jurassic Extinction Event

Just as the Great Dying had reset the evolutionary game board at the end of the Permian, another mass extinction event at the end of the Triassic period would dramatically alter the competitive landscape. Around 201 million years ago, massive volcanic eruptions associated with the breakup of Pangaea triggered another global catastrophe.

This extinction event, while not as severe as the Great Dying, still eliminated about 76% of all species on Earth. The impact was particularly devastating for the crurotarsans, who had dominated terrestrial ecosystems for nearly 30 million years. Their larger body sizes and more specialized lifestyles made them vulnerable to the rapid environmental changes.

Dinosaurs, being generally smaller and more adaptable, weathered this extinction much better. Their efficient respiratory systems and metabolisms gave them a crucial advantage during the environmental upheaval. When the dust settled, dinosaurs found themselves in a world with dramatically reduced competition and wide-open ecological niches waiting to be filled.

Why Dinosaurs Succeeded Where Others Failed

The success of dinosaurs wasn’t due to a single factor, but rather a perfect storm of advantageous traits and lucky timing. Their upright posture allowed for more efficient locomotion, enabling them to travel greater distances in search of food and mates. This was particularly important in the increasingly arid climate of the late Triassic and early Jurassic periods.

Their respiratory systems, featuring air sacs connected to hollow bones, provided superior oxygen delivery to their tissues. This was crucial not just for everyday activities, but also for surviving in the low-oxygen environments that followed major extinction events. Some paleontologists argue that this respiratory system was so efficient that it gave dinosaurs a permanent metabolic advantage over their competitors.

Perhaps most importantly, dinosaurs showed remarkable evolutionary flexibility. Unlike the highly specialized synapsids or crurotarsans, early dinosaurs retained the ability to rapidly adapt to new environments and ecological roles. This flexibility would prove invaluable as Earth’s climate and geography continued to change throughout the Mesozoic era.

The Fate of the Synapsids

While dinosaurs were claiming their throne, what happened to the synapsids that had once ruled the world? Contrary to popular belief, they didn’t simply disappear. Instead, they underwent one of the most dramatic evolutionary transformations in the history of life on Earth.

The surviving synapsids, known as therapsids, became progressively smaller and more mammal-like throughout the Triassic period. Creatures like Morganucodon, weighing only about 30 grams, developed true hair, complex teeth, and increasingly sophisticated brain structures. These tiny survivors were essentially the first true mammals.

For the next 160 million years, these mammalian descendants of the once-mighty synapsids would live in the shadows of the dinosaurs. They survived by occupying small ecological niches that dinosaurs couldn’t or wouldn’t exploit—becoming nocturnal, burrowing underground, or living in trees. Their time would come again, but not until the dinosaurs themselves faced their own extinction event.

Marine Reptiles Fill the Seas

While dinosaurs were conquering the land, an equally dramatic transformation was occurring in the oceans. The marine realm, devastated by the end-Permian extinction, was rapidly being colonized by new groups of reptiles that had evolved from terrestrial ancestors.

Ichthyosaurs, which looked remarkably like modern dolphins despite being reptiles, became the ocean’s new apex predators. These streamlined hunters could reach lengths of over 60 feet and had eyes the size of dinner plates for spotting prey in the murky depths. Meanwhile, plesiosaurs evolved into two distinct forms: long-necked hunters that snatched fish from the water and short-necked giants that could tackle prey as large as other marine reptiles.

The success of these marine reptiles shows that the post-extinction world wasn’t just about dinosaurs replacing land animals—it was about archosaurs and their relatives colonizing every available environment on Earth. The land, sea, and eventually even the air would be dominated by this incredibly successful group of reptiles.

The Rise of the First Giant Dinosaurs

With their competitors largely eliminated, dinosaurs began to experiment with body sizes that would have been impossible in the crowded ecosystems of the Triassic. The late Triassic and early Jurassic periods saw the evolution of the first truly massive dinosaurs, setting the stage for the giants that would dominate the planet for the next 100 million years.

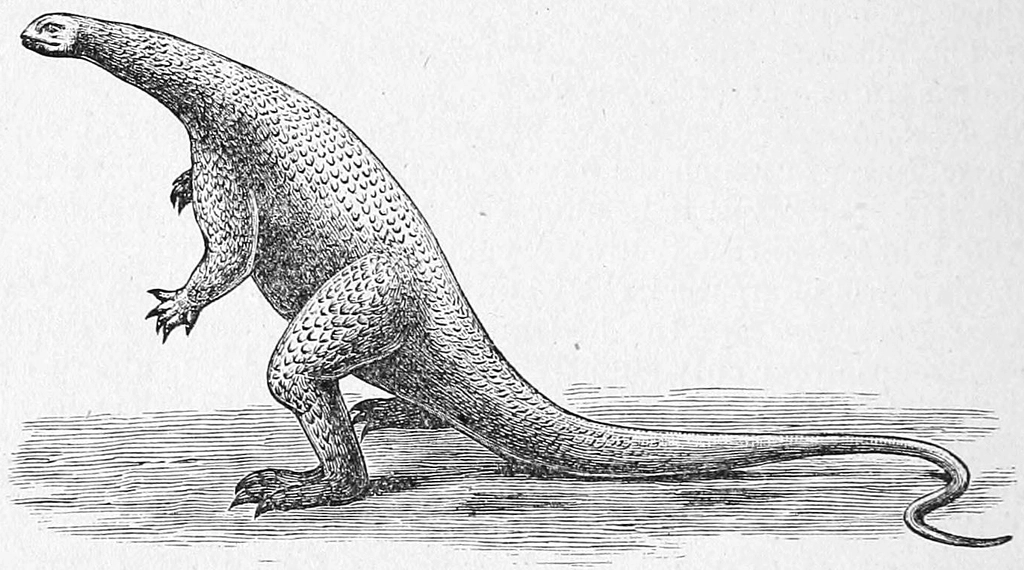

Plateosaurus, one of the first large dinosaurs, reached lengths of up to 33 feet and weighed as much as 4 tons. This massive herbivore showed that dinosaurs could successfully scale up to exploit food resources that were previously inaccessible. Its long neck allowed it to browse vegetation at heights that no other land animal could reach.

The success of these early giants proved that dinosaurs had not just survived the transition from the Triassic to the Jurassic—they had thrived. Their unique combination of efficient metabolism, strong skeletal structure, and adaptive flexibility had given them the tools they needed to become the most successful large vertebrates in Earth’s history.

Ecological Niche Expansion

As dinosaurs diversified throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, they demonstrated an remarkable ability to adapt to virtually every terrestrial ecological niche. Some became massive long-necked herbivores that could process enormous quantities of plant material, while others evolved into swift, pack-hunting predators with razor-sharp teeth and claws.

Perhaps most impressively, some dinosaurs even learned to fly. The evolution of birds from small theropod dinosaurs represents one of the most successful evolutionary transitions in history. These flying dinosaurs were able to exploit aerial niches that had been largely empty since the Permian extinction eliminated many of the early flying insects and gliding reptiles.

This ecological flexibility was perhaps the most important factor in dinosaur success. While their predecessors had often been highly specialized for particular lifestyles, dinosaurs retained the ability to rapidly evolve new forms and behaviors in response to changing environmental conditions. This adaptability would serve them well for over 160 million years of dominance.

The Legacy of Replacement

The story of who early dinosaurs replaced reveals one of the most fundamental truths about evolution: success is often less about being the “best” and more about being in the right place at the right time with the right adaptations. The synapsids and crurotarsans that dinosaurs replaced weren’t inferior creatures—they were highly successful animals that had dominated their respective time periods.

What made dinosaurs successful was their combination of efficient physiology, adaptive flexibility, and sheer evolutionary luck. They happened to have the right traits to survive multiple mass extinction events, and they were positioned to take advantage of the ecological opportunities that these extinctions created.

Today, we can see the descendants of all these ancient groups still thriving in different forms. Birds are living dinosaurs, mammals are the inheritors of the synapsid legacy, and crocodiles represent the last surviving crurotarsans. Each group found its own path to success, but for 160 million years, it was the dinosaurs’ world—and everyone else was just living in it.

The replacement of ancient life forms by early dinosaurs wasn’t just a simple case of survival of the fittest. It was a complex story of mass extinctions, environmental changes, and evolutionary innovation that reshaped life on Earth forever. The animals that dinosaurs replaced—from the mighty synapsids to the armored crurotarsans—weren’t evolutionary failures. They were successful in their own right, but they lacked the specific combination of traits that would prove essential for surviving the catastrophic changes of the late Triassic period. When we look at the fossil record, we see not just the rise of dinosaurs, but the incredible resilience and adaptability of life itself. Each major extinction event that devastated established ecosystems also created new opportunities for innovation and diversification. The story continues today, as birds soar through our skies carrying the genetic legacy of those first small dinosaurs that emerged from the shadows 230 million years ago. What other evolutionary replacements might be happening right now that we’re not even aware of?