When we think about the Mesozoic Era, towering T-Rex and gentle Brontosaurus typically come to mind. But lurking beneath this familiar prehistoric landscape lies a world far more bizarre and extraordinary than any Hollywood blockbuster dared to imagine. Picture creatures that blur the line between mammal and reptile, insects the size of dinner plates, and evolutionary experiments that would make modern scientists question everything they thought they knew about life on Earth.

The Mesozoic Era wasn’t just the “Age of Reptiles” – it was nature’s most audacious laboratory, where life forms pushed the boundaries of possibility in ways that still baffle paleontologists today. From vampire-like dinosaurs to flying reptiles with wingspans rivaling small aircraft, this ancient world harbored secrets that challenge our understanding of evolution itself.

The Vampire Dinosaur That Stalked Ancient China

Deep in the forests of Early Cretaceous China, a peculiar predator prowled with fangs that would make Dracula envious. Epidexipteryx, discovered in 2008, possessed elongated canine teeth that protruded from its mouth like deadly daggers. This crow-sized dinosaur didn’t use these fangs for tearing flesh from large prey – instead, it likely fed on tree sap, insects, and possibly small vertebrates in a feeding style reminiscent of modern vampire bats.

What makes Epidexipteryx truly extraordinary isn’t just its vampire-like appearance, but its bizarre combination of features. This creature sported four ribbon-like tail feathers that served no flight purpose – they were purely for display, making it one of the earliest known examples of ornamental plumage in dinosaur evolution. The discovery shattered conventional wisdom about early bird evolution and revealed that some dinosaurs were experimenting with feathers millions of years before flight became possible.

Giant Insects That Ruled the Skies

The Mesozoic atmosphere contained nearly 50% more oxygen than today, creating perfect conditions for insects to reach absolutely monstrous proportions. Dragonflies with wingspans exceeding two feet patrolled ancient skies, while beetles the size of modern house cats scuttled through prehistoric forests. These aerial giants weren’t just larger versions of their modern counterparts – they were apex predators in their own right.

The increased oxygen levels allowed these insects to develop more efficient respiratory systems, enabling them to sustain the massive body sizes that would be impossible in today’s atmosphere. Some prehistoric cockroaches reached lengths of over six inches, while ancient grasshoppers could leap distances that would put modern Olympic athletes to shame. These creatures dominated their ecosystems for millions of years before declining oxygen levels forced them to downsize or face extinction.

The Dinosaur That Couldn’t Decide What It Wanted to Be

Therizinosaurus presents one of paleontology’s most confusing puzzles – a massive dinosaur that looked like it was assembled from spare parts of entirely different creatures. Standing nearly 16 feet tall and weighing as much as an elephant, this giant sported claws that stretched over three feet long, yet it was completely vegetarian. These enormous talons, initially mistaken for giant turtle ribs, were actually sophisticated plant-processing tools.

The creature’s body plan defied every rule of predator design, featuring a long neck like a sauropod, a bulky body like a ground sloth, and those infamous scythe-like claws that could have easily disemboweled any predator foolish enough to attack. Therizinosaurus represents nature’s most extreme experiment in plant-eating design, proving that evolution sometimes takes the most unexpected paths to solve survival problems.

Prehistoric Gliders That Mastered Four-Winged Flight

Long before birds achieved aerial mastery, the Mesozoic skies were ruled by creatures that pioneered entirely different approaches to flight. Microraptor, a four-winged dinosaur from Early Cretaceous China, sported fully developed flight feathers on both its arms and legs, creating a unique gliding configuration that has no modern equivalent. This crow-sized predator likely lived in trees, using its four wings to glide between branches while hunting small mammals and birds.

The discovery of Microraptor revolutionized our understanding of how flight evolved, suggesting that the transition from ground-dwelling to aerial lifestyle was far more complex than previously imagined. Its iridescent black feathers, preserved in remarkable detail, reveal that these ancient fliers were as concerned with appearance as they were with aerodynamics. The four-winged design eventually gave way to the more efficient two-winged configuration we see in modern birds, but for millions of years, these aerial acrobats ruled the treetops.

The Mesozoic’s Most Successful Failure

While dinosaurs dominated the land, pterosaurs claimed the skies in a reign that lasted over 150 million years. These flying reptiles weren’t dinosaurs at all, but represented an entirely separate evolutionary experiment that achieved powered flight roughly 50 million years before birds appeared. The largest pterosaurs, like Quetzalcoatlus, possessed wingspans approaching 40 feet – larger than most modern aircraft and certainly more maneuverable.

What made pterosaurs truly remarkable wasn’t just their size, but their incredible diversity of ecological niches. Some species developed elaborate head crests for display, others evolved specialized filter-feeding systems for catching fish, and still others became terrestrial stalkers that hunted on foot. Despite their phenomenal success, pterosaurs vanished at the end of the Mesozoic, leaving behind only their bird and bat successors to carry on the dream of vertebrate flight.

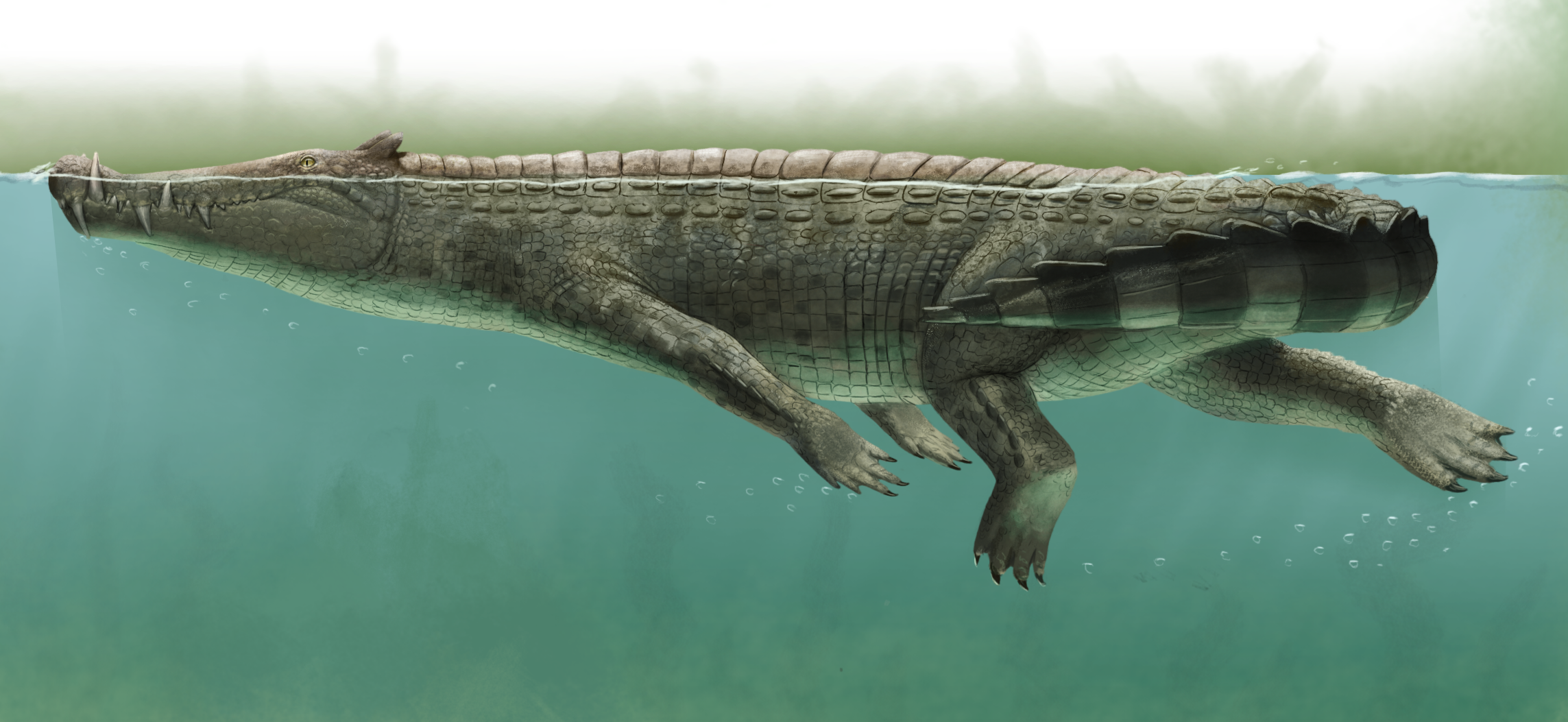

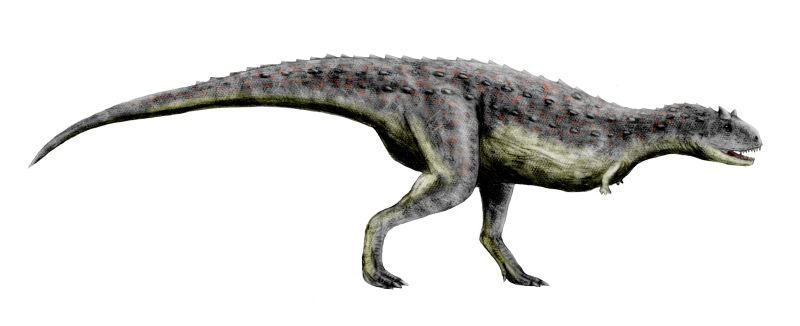

Ancient Crocodiles That Galloped Like Horses

The stereotype of crocodiles as sluggish, water-bound ambush predators would have been laughably inaccurate during the Mesozoic Era. Kaprosuchus, dubbed the “BoarCroc,” possessed long, powerful legs that allowed it to gallop across ancient African landscapes in pursuit of prey. This 20-foot-long predator could probably outrun most modern humans, making it one of the most terrifying land predators of its time.

Even more bizarre was Anatosuchus, a duck-faced crocodile that lived like a modern otter, swimming through rivers and lakes while feeding on fish and small aquatic creatures. These diverse crocodilians occupied ecological niches that modern crocodiles abandoned long ago, from tree-dwelling species to fully terrestrial hunters. The end-Mesozoic extinction event eliminated most of these experimental forms, leaving only the semi-aquatic lifestyle we associate with crocodiles today.

The Dinosaur Nursery That Rewrote Parenting Rules

Maiasaura, the “Good Mother Lizard,” shattered the long-held belief that dinosaurs were cold, uncaring reptiles that simply laid eggs and walked away. Discovered nesting sites in Montana revealed that these duck-billed dinosaurs returned to the same nesting grounds year after year, built elaborate mud nests, and provided extended parental care that rivaled modern birds. Baby Maiasaura stayed in the nest for months, fed and protected by their parents until they were large enough to fend for themselves.

The discovery of Maiasaura nesting colonies provided the first concrete evidence that dinosaurs were capable of complex social behaviors, including communal nesting, cooperative defense, and possibly even primitive forms of education. These findings fundamentally changed how paleontologists viewed dinosaur behavior, transforming them from solitary monsters into sophisticated social creatures with rich emotional lives.

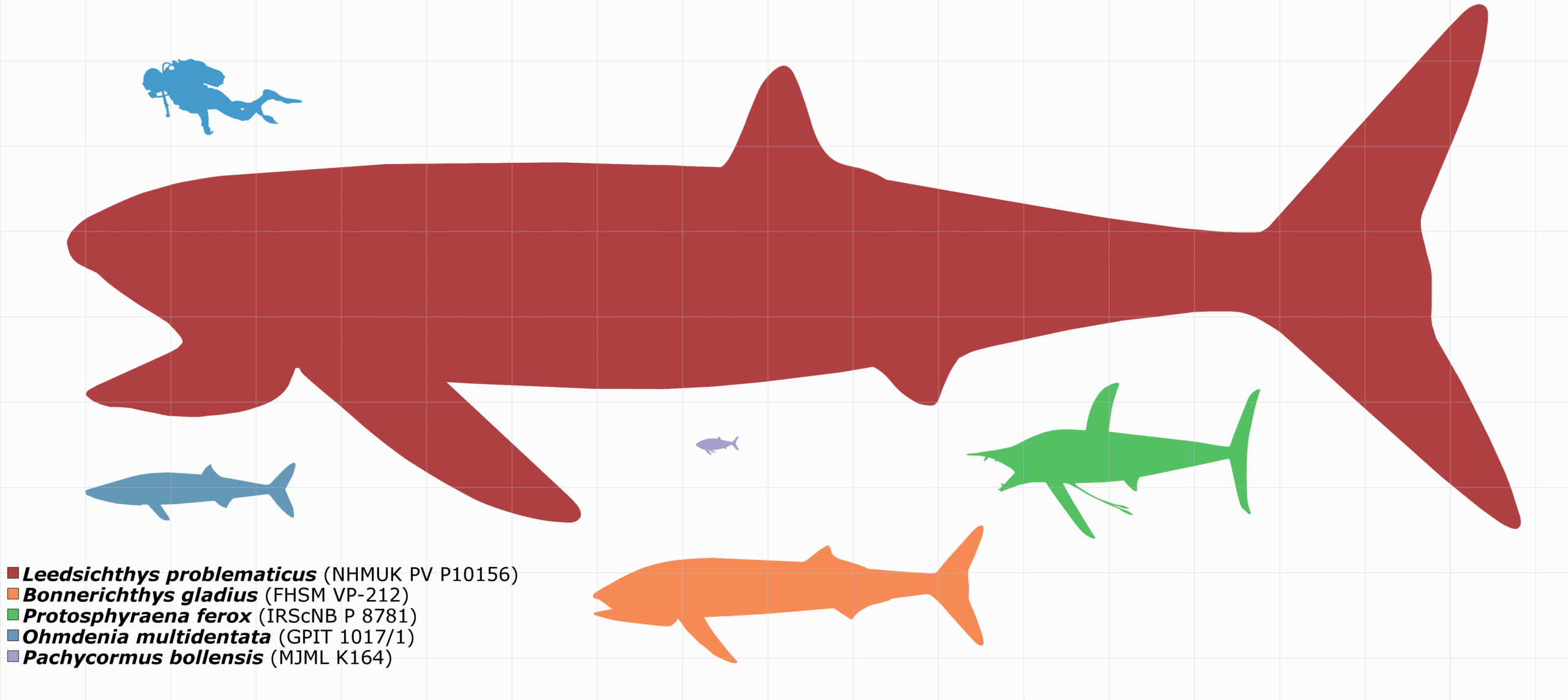

Underwater Dragons That Ruled Ancient Seas

While dinosaurs dominated the land, the Mesozoic oceans were ruled by marine reptiles that would have made sea serpent legends seem tame by comparison. Leedsichthys, a massive fish that could reach lengths of 55 feet, swam alongside plesiosaurs whose necks stretched longer than entire modern whales. These underwater giants developed hunting strategies and body plans that have no modern equivalent, filling ecological niches that remain empty today.

The most fearsome of these marine predators was Liopleurodon, a short-necked plesiosaur with a skull over eight feet long and jaws powerful enough to crush small submarines. Unlike modern marine predators that rely on speed or stealth, these ancient sea monsters were built like living battleships, using brute force and massive size to dominate their aquatic domains. The extinction of these marine giants left the oceans fundamentally different from their Mesozoic heyday.

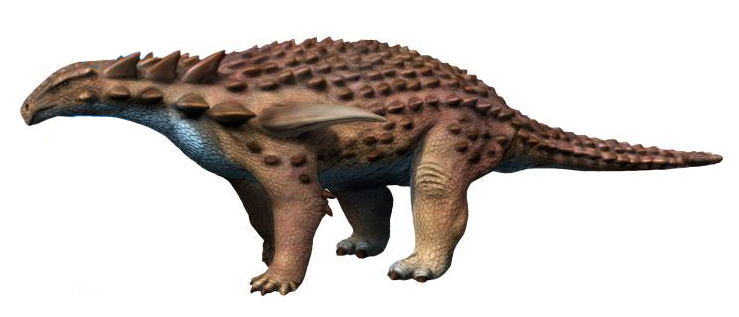

The Feathered Dinosaur That Couldn’t Fly

Borealopelta represents one of the most perfectly preserved dinosaurs ever discovered, a heavily armored herbivore that looked like a medieval knight’s horse crossed with a porcupine. This 18-foot-long ankylosaur was covered in protective plates and spikes, but what truly stunned paleontologists was the preservation of its original coloration – a reddish-brown camouflage pattern that would have helped it blend into Late Cretaceous forests.

The discovery of Borealopelta’s coloration provided the first direct evidence of dinosaur camouflage, suggesting that even heavily armored species relied on stealth to avoid predators. The preservation was so exceptional that scientists could analyze the dinosaur’s last meal, revealing details about Late Cretaceous plant communities and feeding behaviors that would have been impossible to determine from bones alone.

Tiny Mammals That Turned the Tables

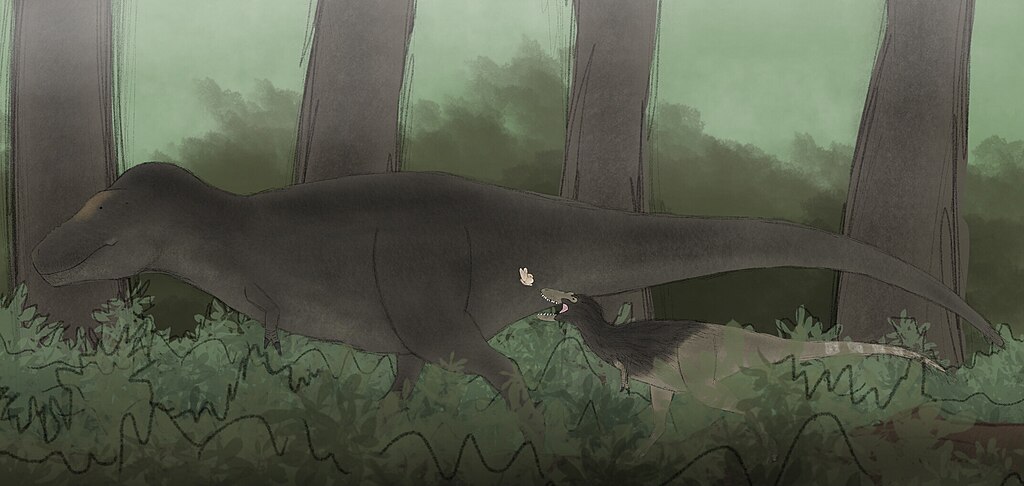

While dinosaurs dominated the Mesozoic landscape, early mammals were quietly developing strategies that would eventually inherit the Earth. Repenomamus, a badger-sized mammal from Early Cretaceous China, shocked paleontologists when fossilized remains were discovered with baby dinosaur bones in its stomach. This furry predator actively hunted young dinosaurs, proving that mammals weren’t just cowering in the shadows waiting for their moment.

Even more remarkable was the discovery of Castorocauda, a beaver-like mammal that had already mastered aquatic life while dinosaurs were still experimenting with basic body plans. These early mammals developed sophisticated behaviors, complex social structures, and diverse ecological adaptations that positioned them perfectly for post-extinction dominance. Their small size and adaptability became their greatest advantages when the asteroid impact changed everything.

The Dinosaur That Fished Like a Modern Heron

Baryonyx revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur diets when paleontologists discovered fossilized fish scales in its stomach cavity. This 30-foot-long predator possessed a crocodile-like snout filled with 96 sharp teeth, perfectly designed for catching slippery fish rather than hunting other dinosaurs. Its massive thumb claws, initially thought to be weapons, were actually sophisticated fishing tools used to spear prey from rivers and lakes.

The discovery of Baryonyx proved that dinosaurs had diversified into nearly every conceivable ecological niche, including specialized piscivores that competed directly with crocodiles for aquatic resources. This fish-eating giant likely waded through shallow waters like modern herons, using its keen eyesight and lightning-fast reflexes to snatch fish from the water with surgical precision.

Ancient Flowers That Sparked an Evolutionary Revolution

The appearance of flowering plants during the Mesozoic Era triggered one of the most dramatic evolutionary explosions in Earth’s history. These colorful newcomers didn’t just add beauty to prehistoric landscapes – they fundamentally altered every ecosystem they entered, creating new food webs, pollination relationships, and evolutionary pressures that shaped the modern world. The co-evolution of flowers and insects drove both groups to unprecedented diversity and complexity.

What makes this botanical revolution even more remarkable is its speed – flowering plants went from complete absence to global dominance in less than 50 million years, a blink of an eye in geological time. This rapid expansion created new opportunities for herbivorous dinosaurs while simultaneously providing the energy-rich fruits and seeds that would fuel the rise of modern mammalian diversity.

The Dinosaur That Evolved Into a Living Swiss Army Knife

Carnotaurus, the “Meat-Eating Bull,” represents one of evolution’s most specialized predatory designs. This massive theropod possessed forward-facing horns above its eyes and arms so reduced they lacked elbows entirely, making it appear like a demonic bull with legs. Its body was built for pure speed, with long, powerful legs that could propel its two-ton frame at speeds approaching 35 miles per hour.

The creature’s unique anatomy suggests it was a specialist hunter that relied on devastating head-butting attacks to subdue prey, using its horned skull like a battering ram. Unlike other large predators that used their arms for grappling, Carnotaurus evolved into a living missile, sacrificing versatility for absolutely devastating effectiveness in its chosen hunting style.

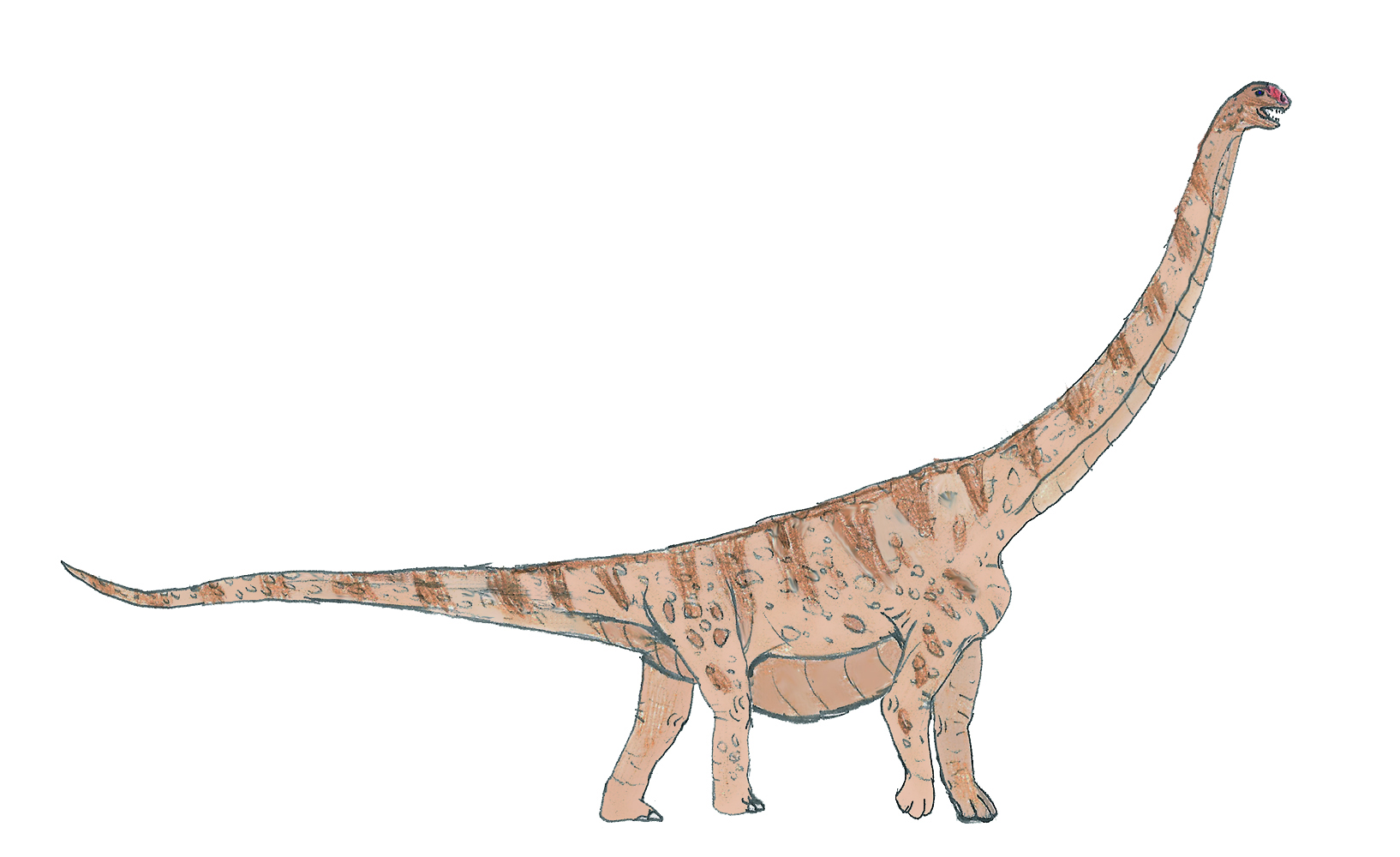

Prehistoric Ecosystem Engineers That Shaped Continents

Long before humans learned to modify landscapes, Mesozoic herbivores were actively engineering entire ecosystems through their feeding and nesting behaviors. Massive sauropods like Argentinosaurus didn’t just eat plants – they created vast networks of paths and clearings that influenced plant distribution, water flow, and soil composition across entire continents. Their daily migrations moved nutrients across hundreds of miles, effectively fertilizing enormous areas.

These gentle giants also served as mobile seed dispersers, carrying plant species to new territories in their digestive systems and creating the first continental-scale conservation corridors. The loss of these ecosystem engineers at the end of the Mesozoic fundamentally altered how nutrients and energy flowed through natural systems, effects that still influence modern ecosystems today.

The Final Curtain: When Giants Walked Their Last Mile

The end of the Mesozoic Era wasn’t just the conclusion of the dinosaur age – it was the closing of one of life’s most ambitious chapters. The asteroid impact that ended this remarkable period eliminated not just dinosaurs, but an entire world of evolutionary experiments that had been 165 million years in the making. Yet the legacy of these prehistoric innovators lives on in every bird that takes flight, every flower that blooms, and every mammal that nurtures its young.

The Mesozoic Era’s strangest creatures remind us that evolution is nature’s greatest artist, constantly pushing the boundaries of what’s possible and creating forms of life that surpass our wildest imagination. These ancient pioneers paved the way for the modern world, proving that sometimes the most successful innovations come from the most unexpected experiments. What other evolutionary surprises might be waiting in the fossil record, still hidden beneath millions of years of stone and time?