Picture this: You’re floating in crystal-clear waters, surrounded by nothing but endless blue. Suddenly, a shadow passes overhead—not a cloud, but something far more terrifying. A creature longer than a school bus, armed with teeth like railroad spikes, glides through the ancient ocean with deadly grace. Welcome to the Mesozoic Era, where sharks didn’t just survive—they absolutely dominated every corner of the marine world.

When Giants First Emerged from the Deep

The Mesozoic Era began around 252 million years ago with a world still recovering from the most devastating mass extinction in Earth’s history. As life slowly rebuilt itself, sharks seized their moment to evolve into forms that would make today’s great whites look like goldfish. These weren’t just bigger versions of modern sharks—they were evolutionary masterpieces, perfectly adapted to rule seas that teemed with marine reptiles, early fish, and countless other prey species.

During this incredible 186-million-year span, sharks underwent some of the most dramatic evolutionary changes in their entire lineage. The warm, shallow seas that covered much of the planet provided the perfect breeding ground for these apex predators to experiment with new body shapes, hunting strategies, and feeding mechanisms. Some developed crushing jaws for shellfish, others grew to massive sizes to hunt large prey, and still others perfected the art of speed and agility.

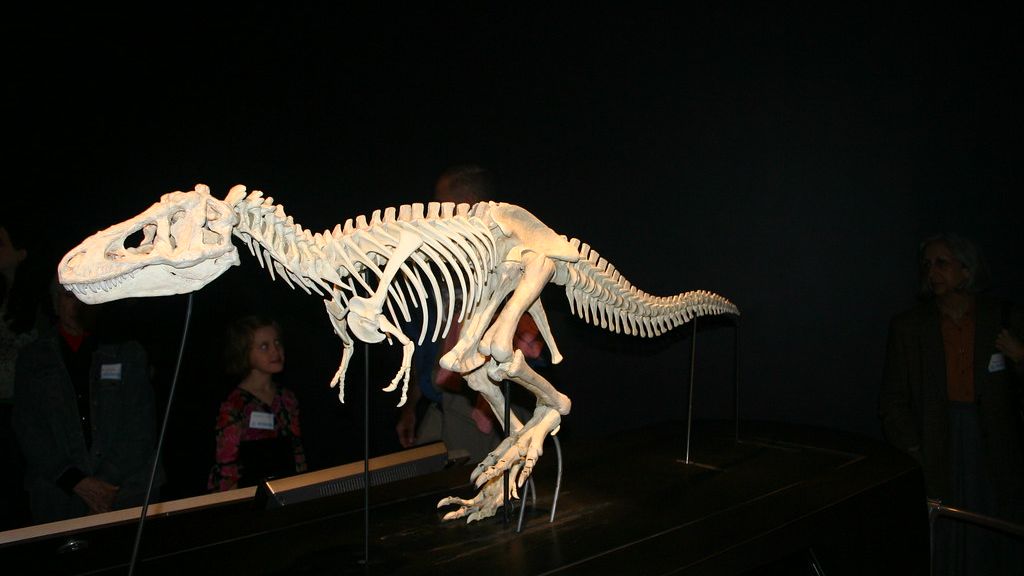

Hybodus: The Swiss Army Knife of Prehistoric Sharks

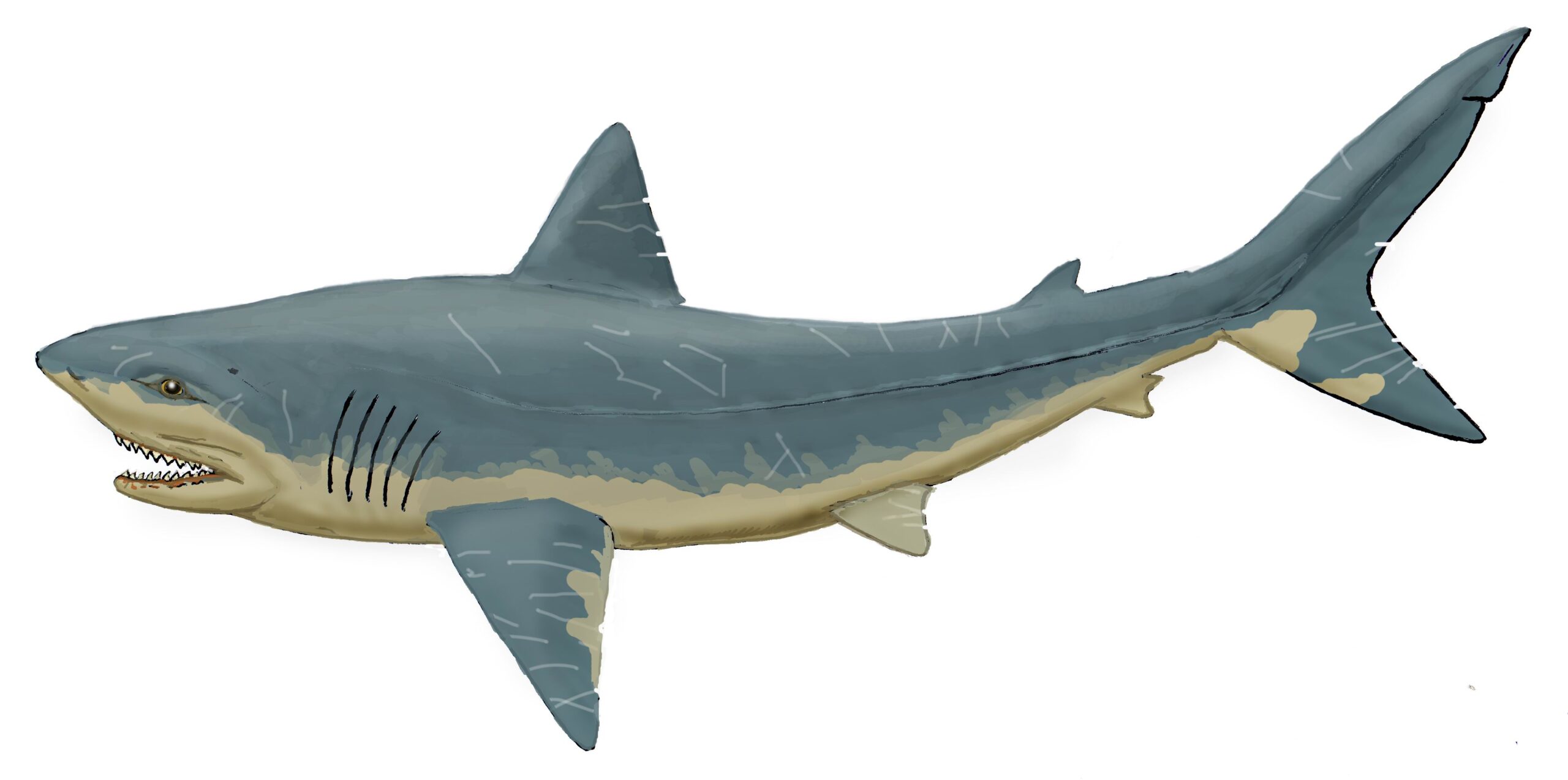

Meet Hybodus, perhaps the most successful shark design of the Mesozoic seas. This remarkable predator lived for over 100 million years, spanning from the Late Permian through the Cretaceous period—a testament to its incredible adaptability. What made Hybodus so special wasn’t just its longevity, but its innovative approach to feeding that would make any modern multi-tool jealous.

Hybodus possessed two distinct types of teeth in its mouth simultaneously: sharp, pointed teeth for catching slippery fish and flat, crushing teeth for cracking open shellfish and crustaceans. This dual-tooth system was like having both a knife and a nutcracker built into the same jaw. The shark could literally switch between hunting strategies mid-meal, making it one of the most versatile predators the oceans have ever seen.

Cretoxyrhina: The Ginsu Shark That Terrorized the Western Interior Seaway

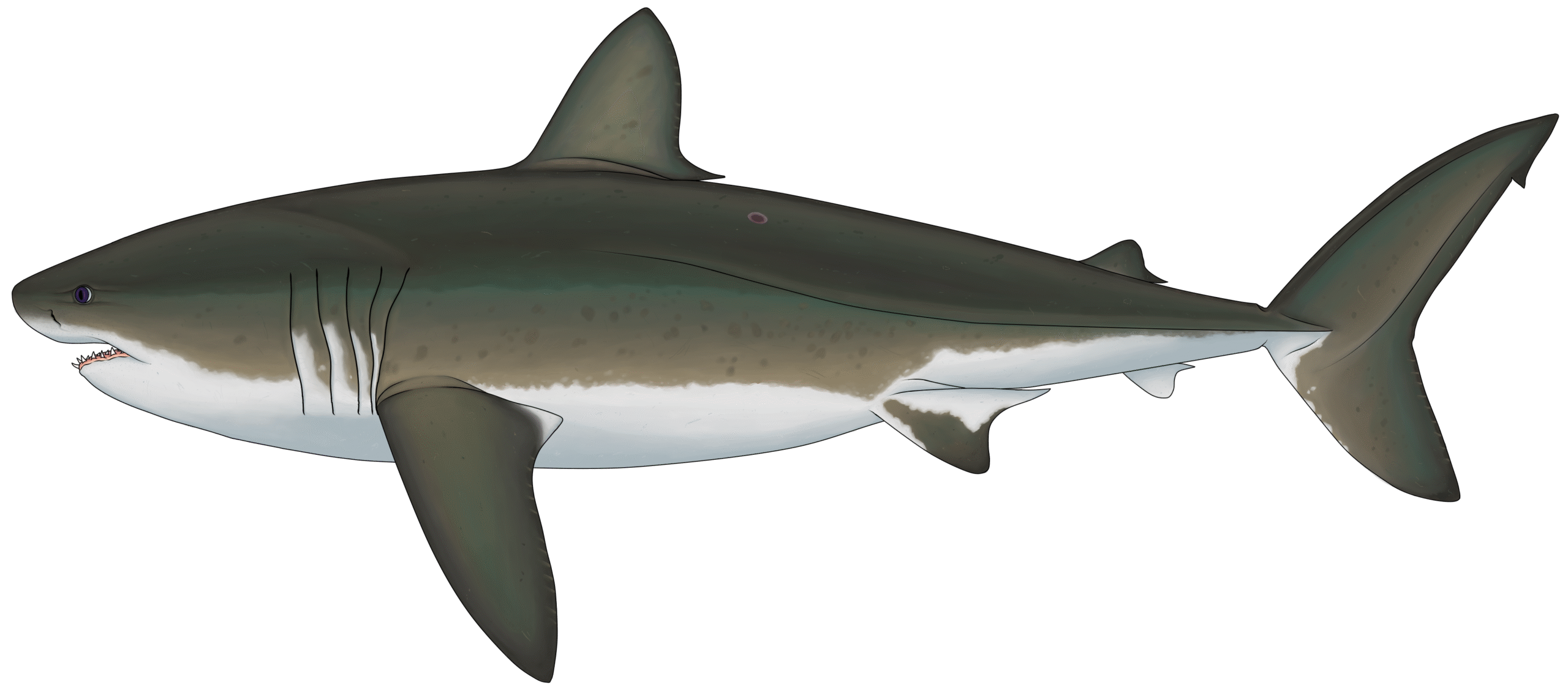

If Hybodus was the Swiss Army knife, then Cretoxyrhina was the chainsaw of Mesozoic sharks. This 24-foot monster earned its nickname “Ginsu shark” from paleontologists who marveled at its razor-sharp teeth and incredible cutting power. Swimming through the Western Interior Seaway that split North America in half, Cretoxyrhina was the ultimate marine predator of its time.

What’s truly shocking about Cretoxyrhina is the evidence of its feeding behavior preserved in the fossil record. Paleontologists have found bite marks from this shark on marine reptiles, including massive mosasaurs and plesiosaurs. Think about that for a moment—this shark was taking bites out of creatures that were themselves apex predators, some reaching lengths of 40 feet or more.

The teeth of Cretoxyrhina were engineering marvels, designed like serrated blades that could slice through flesh and bone with equal ease. These weren’t just for show either; fossil evidence shows that this shark regularly fed on large vertebrates, making it one of the most formidable predators in an ocean already packed with giants.

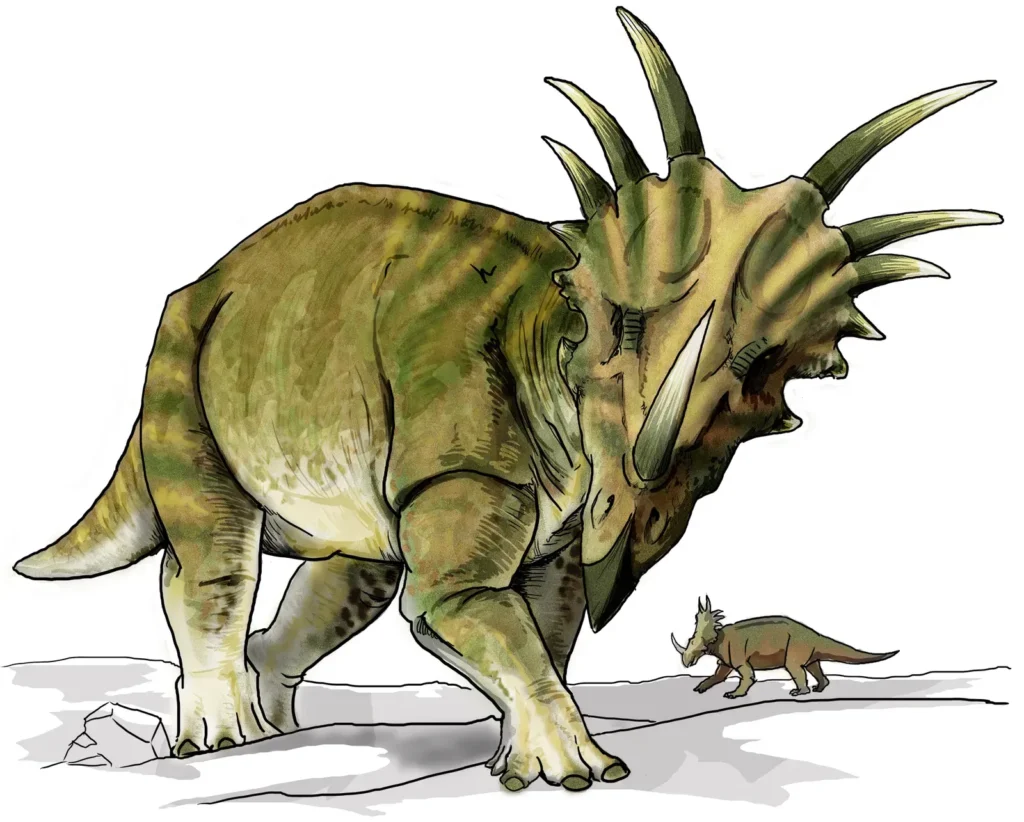

Ptychodus: The Gentle Giant with a Crushing Personality

Not every Mesozoic shark was a bloodthirsty predator hunting marine reptiles. Ptychodus represents one of the most fascinating examples of evolutionary specialization—a massive shark that chose the path of the gentle giant. Growing up to 35 feet in length, this enormous creature was essentially the whale shark of its era, but with a twist that would make your dentist cringe.

Instead of the needle-sharp teeth we associate with sharks, Ptychodus had developed a mouth full of flat, crushing teeth that looked more like cobblestones than cutting implements. These weren’t designed for slicing through flesh, but for crushing shellfish, ammonites, and other hard-shelled creatures that littered the sea floor. Imagine a shark the size of a city bus gently cruising along the bottom, vacuuming up clams and oysters like an underwater bulldozer.

Squalicorax: The Crow Shark That Cleaned Up After Giants

Every ecosystem needs its cleanup crew, and Squalicorax filled that role perfectly in the Mesozoic seas. This 16-foot shark, often called the “crow shark,” was the ultimate opportunist—part scavenger, part active predator, and completely essential to the marine ecosystem’s balance. Like crows in terrestrial environments, Squalicorax was incredibly intelligent and adaptable.

What makes Squalicorax particularly fascinating is its feeding behavior. While it certainly hunted live prey, it also served as nature’s garbage disposal, cleaning up after the massive marine battles that occurred between giant reptiles. When a 60-foot mosasaur died, Squalicorax would arrive in schools to strip the carcass clean, preventing the spread of disease and recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem.

The teeth of Squalicorax tell a story of versatility—sharp enough to cut through flesh, but sturdy enough to handle the tough job of processing carrion. These sharks were so successful that they survived the asteroid impact that ended the Mesozoic Era, proving that sometimes being the cleanup crew is the best survival strategy.

Cardabiodon: The Mysterious Mackerel Shark

Some sharks from the Mesozoic Era remain tantalizingly mysterious, and Cardabiodon is perhaps the most enigmatic of all. Known primarily from isolated teeth found in Late Cretaceous rocks, this mackerel shark has captured the imagination of paleontologists who are still trying to piece together its true size and ecological role. What we do know is absolutely fascinating and more than a little terrifying.

The teeth of Cardabiodon are massive—some specimens measure over 2 inches in length with razor-sharp edges and distinctive serrations. Based on tooth-to-body-size ratios from modern sharks, scientists estimate that Cardabiodon could have reached lengths of 20 feet or more. But here’s where it gets really interesting: these teeth are found in the same fossil deposits as massive marine reptiles, suggesting that this shark was sharing the seas with some of the largest predators ever to swim.

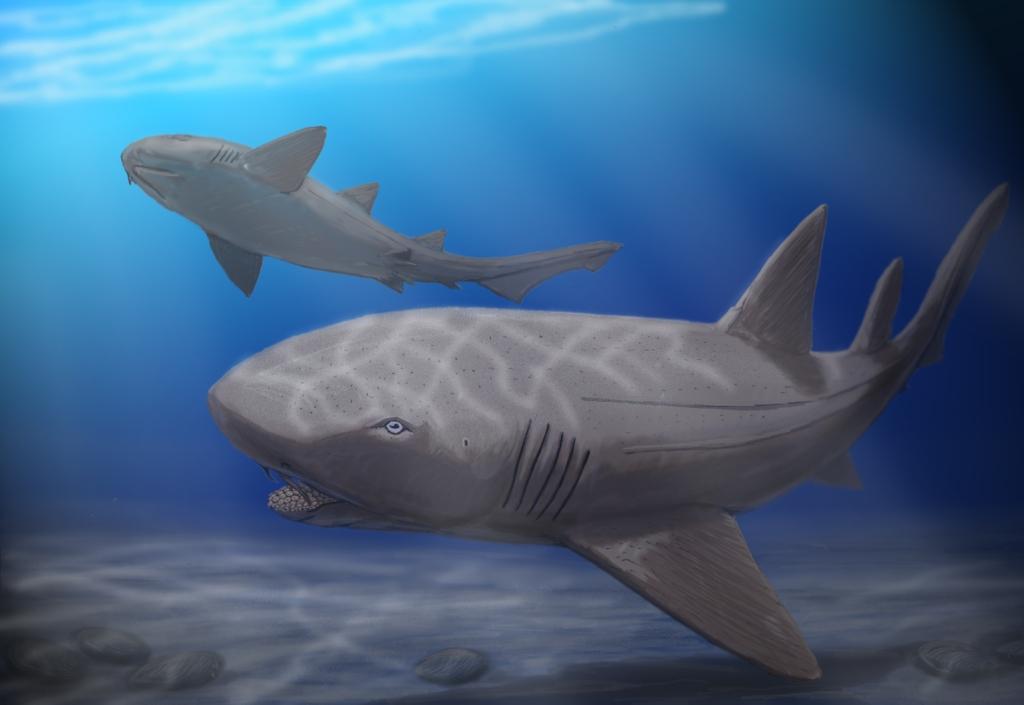

Scapanorhynchus: The Goblin Shark’s Ancient Ancestor

If you’ve ever seen a goblin shark and thought it looked like something from a prehistoric nightmare, you’re not wrong. Scapanorhynchus, swimming through Mesozoic seas over 100 million years ago, was the ancient ancestor of today’s living fossil. This shark had one of the most unusual hunting adaptations in the entire fossil record—a projectile jaw that could shoot out like a spring-loaded trap.

The most remarkable thing about Scapanorhynchus is how little it has changed over millions of years. When you look at a modern goblin shark, you’re essentially seeing a creature that has remained virtually unchanged since the Cretaceous period. This evolutionary stability suggests that Scapanorhynchus had perfected its hunting strategy so completely that nature saw no need to improve upon it.

The elongated snout of Scapanorhynchus was packed with electrical sensors that could detect the slightest muscle contractions of hidden prey. Once a victim was located, the shark’s jaw would explosively extend outward, snatching the prey before it even knew what hit it. This ambush predator was the ultimate lurker of the deep Mesozoic seas.

Anacoracidae: The Diverse Family of Sand Tiger Ancestors

The Anacoracidae family represents one of the most successful groups of Mesozoic sharks, with species ranging from small coastal hunters to massive open-ocean predators. These sharks were the ancestors of modern sand tiger sharks, but they had evolved into forms that were far more diverse and specialized than their modern descendants. Each species had carved out its own ecological niche in the competitive Mesozoic marine environment.

What’s particularly striking about the Anacoracidae is how they demonstrate the incredible diversity of shark evolution during the Mesozoic Era. Some species developed long, narrow teeth perfect for catching slippery fish, while others evolved broader, more robust teeth for crushing prey. This family shows us that even within a single lineage, sharks were constantly experimenting with new forms and functions.

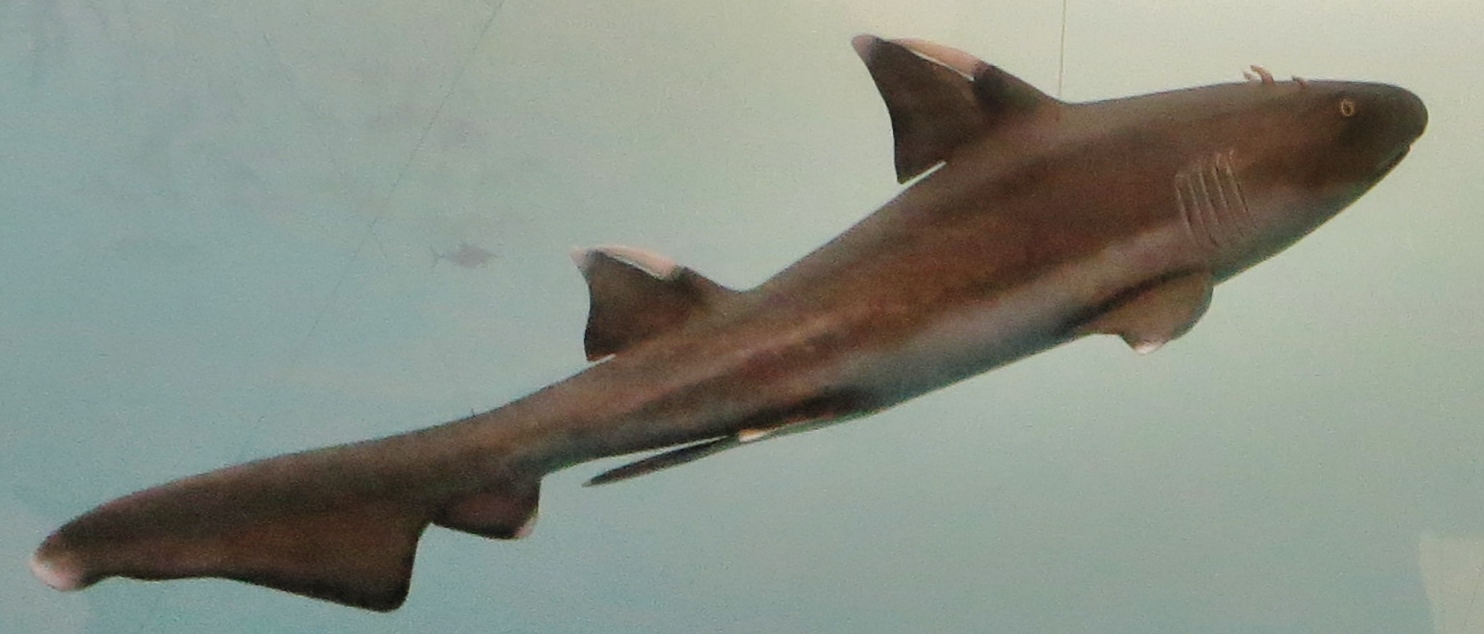

The Hexanchidae: Living Fossils from the Mesozoic

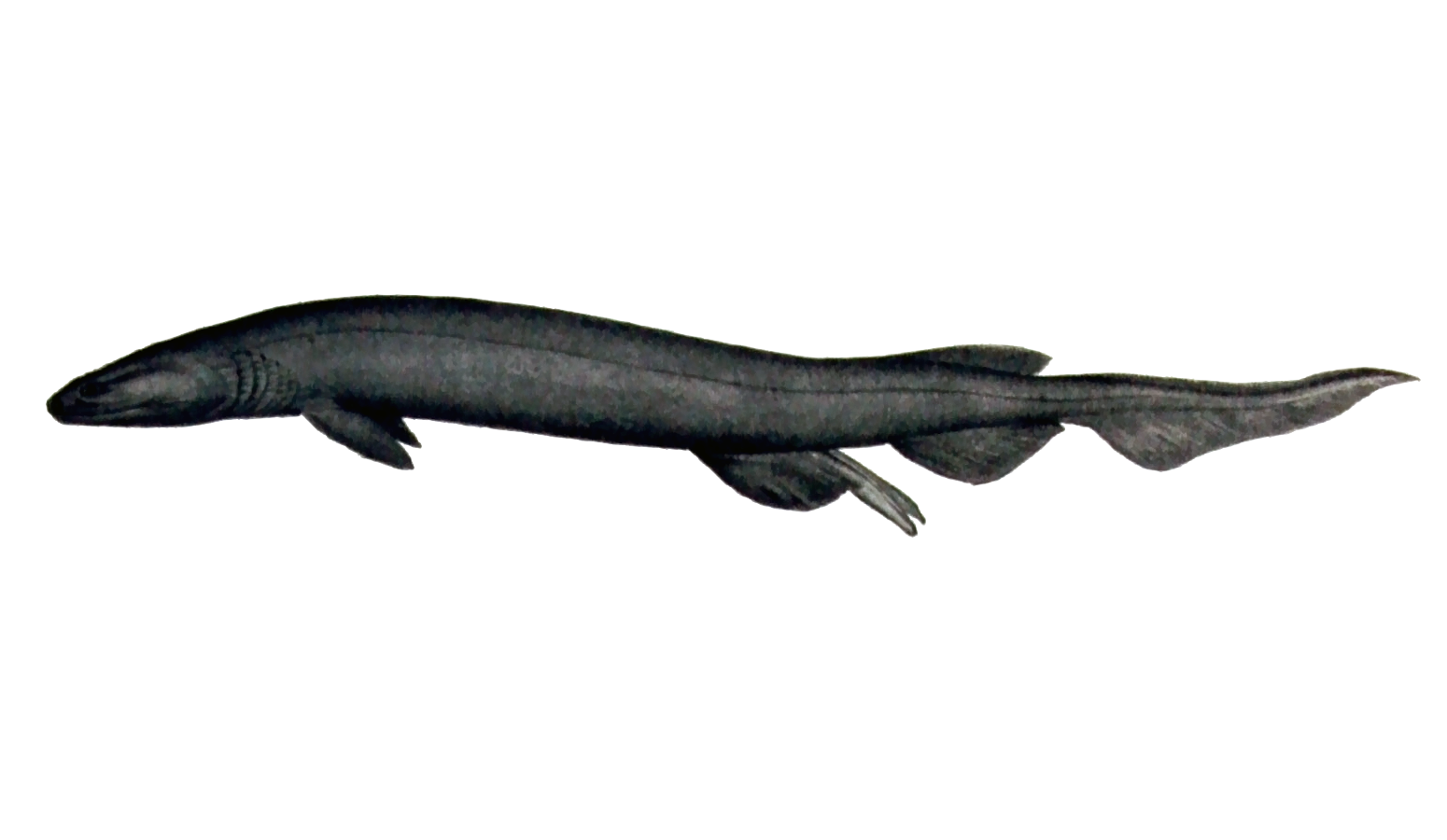

Some sharks from the Mesozoic Era never really left—they just kept swimming. The Hexanchidae family, including the cow sharks and frilled sharks, represents one of the most ancient lineages of sharks that managed to survive from the Mesozoic Era into modern times. These living fossils give us a direct window into what ancient shark diversity looked like millions of years ago.

The most remarkable member of this family is the frilled shark, which looks more like a sea serpent than a traditional shark. With its eel-like body and primitive gill slits, the frilled shark is essentially a swimming fossil that has changed very little since the Mesozoic Era. When deep-sea explorers encounter these creatures today, they’re literally face-to-face with a design that was perfected over 150 million years ago.

What makes the Hexanchidae so special is their combination of primitive features with highly specialized hunting adaptations. These sharks retained the basic body plan that worked so well in the Mesozoic seas while fine-tuning their predatory abilities to survive in the deep ocean environments where they continue to thrive today.

Feeding Strategies That Defined an Era

The diversity of feeding strategies among Mesozoic sharks was nothing short of revolutionary. These ancient predators didn’t just stick to one successful formula—they experimented with every possible way to make a living in the ocean. From the shell-crushing specialists like Ptychodus to the large-vertebrate hunters like Cretoxyrhina, each species had evolved its own unique approach to survival.

Perhaps most impressive was how these sharks managed to coexist with the massive marine reptiles that dominated the headlines of Mesozoic seas. Rather than competing directly with 60-foot mosasaurs and long-necked plesiosaurs, many shark species found ways to complement these giants. Some became specialized scavengers, others focused on prey that the reptiles couldn’t catch, and still others grew large enough to hunt the reptiles themselves.

This ecological partitioning was so effective that sharks actually thrived during the Mesozoic Era, diversifying into more forms than ever before or since. The secret was specialization—each species becoming the absolute best at its particular role in the marine ecosystem.

The Great Extinction and Shark Survival

When the asteroid hit Earth 66 million years ago, ending the Mesozoic Era, it triggered one of the most devastating mass extinctions in planetary history. The impact killed off the dinosaurs, devastated marine ecosystems, and eliminated countless species from the fossil record. Yet remarkably, many shark lineages managed to survive this catastrophic event, though they paid a heavy price for their persistence.

The extinction event was particularly brutal for large sharks. Giants like Cretoxyrhina and Ptychodus disappeared forever, unable to find enough food in the post-impact oceans. However, smaller, more adaptable species survived by switching to different prey sources and adjusting their hunting strategies. This survival pattern teaches us something profound about evolution—sometimes being the biggest and strongest isn’t as important as being flexible and adaptable.

The sharks that survived the extinction became the ancestors of all modern shark species. In many ways, we’re still living with the evolutionary consequences of that catastrophic day 66 million years ago, when the age of giant sharks came to an abrupt end.

Fossil Evidence and Scientific Discoveries

Our understanding of Mesozoic sharks comes primarily from fossilized teeth, since shark skeletons are made of cartilage that rarely preserves well. However, these teeth tell incredibly detailed stories about ancient shark biology and behavior. Each tooth is like a fingerprint, revealing not just the species but also the age of the individual shark and its feeding habits.

Some of the most exciting discoveries in recent years have come from exceptionally preserved specimens that include not just teeth but also skin impressions, vertebrae, and even stomach contents. These rare finds have revolutionized our understanding of how these ancient sharks lived, hunted, and interacted with their environment. One particularly stunning specimen of Cretoxyrhina even preserved the remains of a marine reptile in its stomach area.

The geographic distribution of shark fossils also tells us about ancient ocean currents, temperature patterns, and the movement of continents during the Mesozoic Era. Sharks were excellent indicators of marine ecosystem health, and their fossil record provides crucial insights into how ancient oceans functioned.

Modern Implications and Evolutionary Lessons

The story of Mesozoic sharks isn’t just ancient history—it has profound implications for understanding modern shark evolution and conservation. Many of the evolutionary innovations that first appeared in Mesozoic sharks are still present in modern species, proving that these ancient predators were incredibly successful at solving the challenges of marine life.

Perhaps most importantly, the Mesozoic shark fossil record shows us how these animals have repeatedly bounced back from mass extinctions and environmental changes. This resilience gives us hope for modern shark conservation efforts, but it also reminds us that even the most successful lineages can be pushed to extinction if environmental pressures become too severe.

The diversity of Mesozoic sharks also challenges our modern perception of what sharks should look like and how they should behave. These ancient species show us that sharks are capable of far more evolutionary flexibility than we might expect, suggesting that modern species might be able to adapt to changing ocean conditions better than we currently understand.

The Legacy of Mesozoic Marine Dominance

The Mesozoic Era represents the golden age of shark evolution, a time when these predators reached levels of diversity and specialization that have never been matched since. From the massive crushing jaws of Ptychodus to the lightning-fast strikes of Scapanorhynchus, these ancient sharks pushed the boundaries of what was possible in marine predation.

Today’s sharks are essentially the survivors of that incredible evolutionary experiment. Every modern species carries within its DNA the accumulated wisdom of millions of years of Mesozoic evolution, refined through countless environmental challenges and mass extinctions. When we look at a great white shark or a hammerhead, we’re seeing the direct descendants of those Mesozoic giants.

The legacy of Mesozoic sharks extends far beyond their evolutionary descendants. These ancient predators helped shape the very structure of marine ecosystems, influencing everything from the evolution of bony fish to the development of marine reptiles. Their impact on ocean life was so profound that we’re still discovering new aspects of their ecological influence millions of years later.

The sharks that ruled the Mesozoic seas were far more than simple predators—they were evolutionary innovators, ecological engineers, and masters of adaptation. Their incredible diversity shows us that success in nature comes not from finding one perfect solution, but from constantly experimenting with new approaches to life’s challenges. These ancient giants remind us that our modern oceans are just the latest chapter in a story that has been unfolding for hundreds of millions of years. What lessons do you think we can learn from these prehistoric masters of the sea?