Picture this: you’re standing on the shores of an ancient sea 70 million years ago, watching as massive shadows glide beneath the waves. Suddenly, the water erupts in a violent display of prehistoric power as two titans clash in a battle that would make any modern predator look like a house cat. This isn’t science fiction—this was reality during the Late Cretaceous period, when the oceans teemed with some of the most formidable predators our planet has ever known.

The mosasaurs weren’t just big lizards that happened to live in water. These were apex predators that ruled the ancient seas with an iron jaw, equipped with crushing bite forces that could snap a small car in half. But here’s where things get interesting: while most dinosaurs stuck to land, some brave souls ventured into the water, creating one of prehistory’s most fascinating what-if scenarios. Could these marine reptilian monsters have taken on any dinosaur that dared to swim?

The Mosasaur Dynasty: Ocean Overlords of the Cretaceous

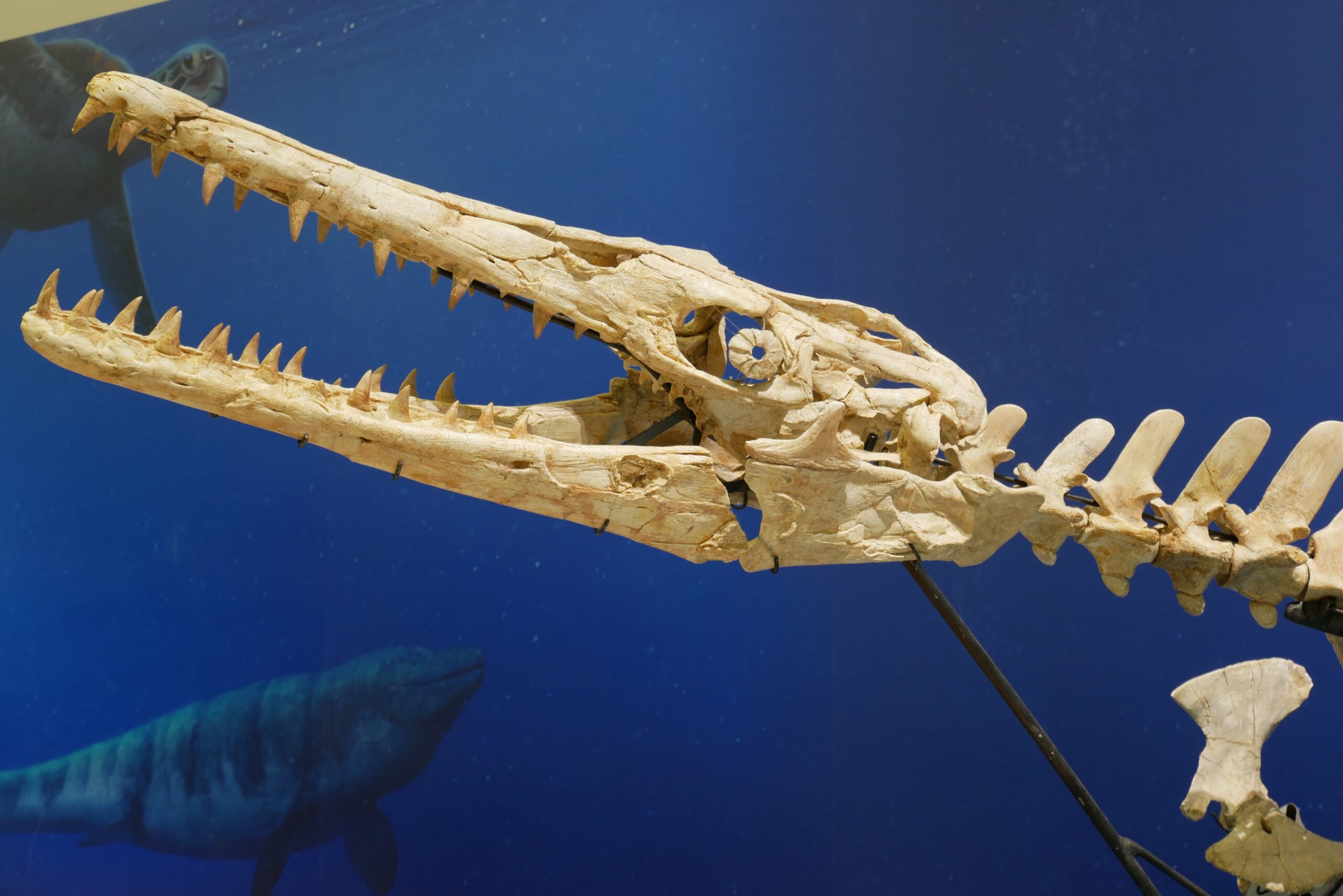

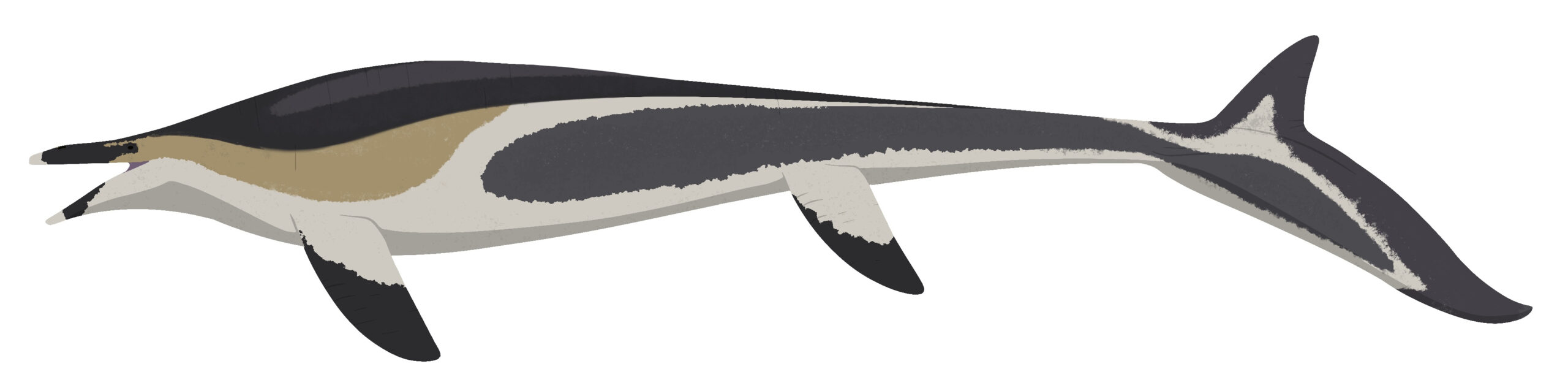

Mosasaurs weren’t dinosaurs—they were marine reptiles that evolved from land-dwelling lizards, transforming into oceanic nightmares over millions of years. These creatures dominated the seas from roughly 100 to 66 million years ago, growing to lengths that would make today’s great white sharks look like minnows.

The largest mosasaur species, like Mosasaurus hoffmanni, reached lengths of up to 56 feet, with skulls alone measuring over 5 feet long. Their bodies were perfectly adapted for aquatic hunting, featuring powerful flippers, a massive tail for propulsion, and jaws lined with razor-sharp teeth designed for gripping and crushing.

What made these predators truly terrifying was their combination of size, speed, and intelligence. Unlike modern marine reptiles, mosasaurs had excellent vision both above and below water, allowing them to spot prey from incredible distances. Their streamlined bodies could accelerate rapidly, making them ambush predators par excellence.

Swimming Dinosaurs: The Aquatic Adventurers

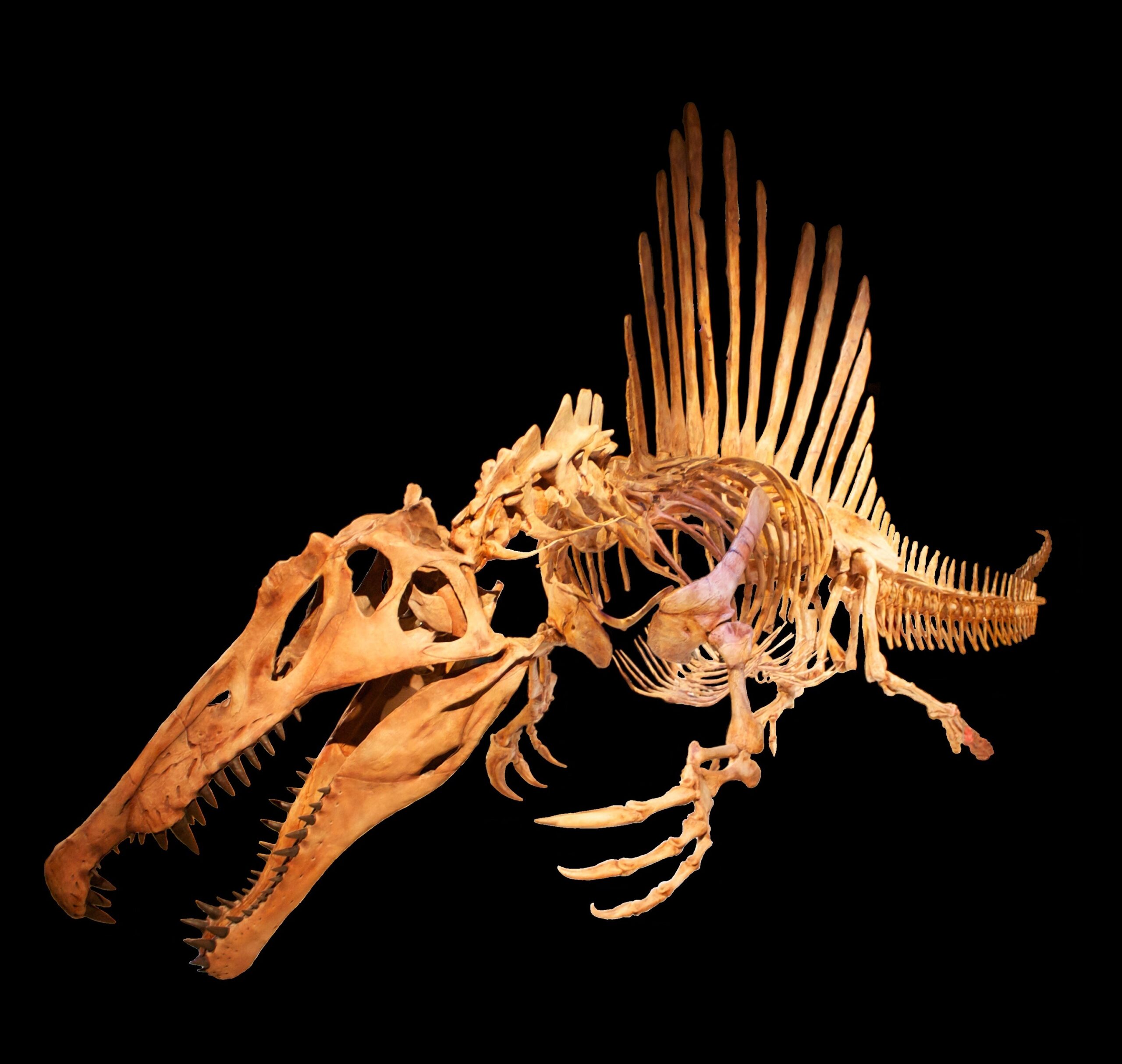

While most dinosaurs preferred solid ground beneath their feet, several species took to the water either by choice or necessity. The most famous of these aquatic dinosaurs was Spinosaurus, a massive predator that recent discoveries have revealed was far more adapted to water than previously thought.

Spinosaurus aegyptiacus stretched up to 50 feet in length and sported a distinctive sail on its back, paddle-like feet, and a crocodile-like skull perfect for catching fish. This dinosaur spent considerable time in rivers and coastal waters, making it a prime candidate for a potential mosasaur encounter.

Other swimming dinosaurs included various hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) that could swim across rivers and lakes, and some smaller theropods that lived near water sources. However, none of these creatures were as perfectly adapted for aquatic life as the mosasaurs, setting up an intriguing David-and-Goliath scenario in reverse.

Size Matters: Comparing the Giants

When it comes to prehistoric predators, size often determines the outcome of any encounter. The largest mosasaurs could reach lengths of 56 feet, making them longer than most swimming dinosaurs. However, Spinosaurus could match or even exceed this length, creating a relatively even playing field in terms of sheer bulk.

But here’s where the comparison gets fascinating: Mosasaurs were built like living torpedoes, with every inch of their body designed for aquatic dominance. Their weight distribution, muscle mass, and bone density were all optimized for underwater combat. Spinosaurus, while impressive, was essentially a land animal that learned to swim, like a bodybuilder trying to compete in the Olympic swimming pool.

The weight advantage went to the mosasaurs, whose dense bones and massive skulls gave them a significant edge in underwater confrontations. A full-grown Mosasaurus could weigh up to 30 tons, while Spinosaurus, despite its length, was built more lightly at around 20 tons maximum.

Bite Force: The Ultimate Weapon

If prehistoric combat came down to bite force, mosasaurs would win hands down—or should we say, jaws down. Recent studies estimate that the largest mosasaurs possessed bite forces exceeding 40,000 pounds per square inch, rivaling or surpassing even Tyrannosaurus rex.

Their jaws were equipped with two rows of sharp, recurved teeth designed to grip slippery prey and prevent escape. Unlike many dinosaurs that relied on slashing attacks, mosasaurs were crushers, capable of breaking through the shells of giant ammonites and the bones of other marine reptiles.

Spinosaurus, while possessing a formidable bite, was primarily a fish-eater with a relatively narrow skull and conical teeth better suited for catching slippery prey than crushing bone. In a confrontation, the mosasaur’s superior bite force would prove devastating, potentially ending the fight with a single well-placed attack to the neck or spine.

Speed and Agility: Masters of Their Domain

In the aquatic arena, mosasaurs were like Formula 1 race cars, while swimming dinosaurs were more like pickup trucks trying to navigate a race track. The mosasaur’s body plan was the result of millions of years of evolution specifically for marine environments, creating creatures that could accelerate, turn, and maneuver with deadly precision.

Their powerful tail flukes could propel them through the water at estimated speeds of up to 30 mph in short bursts, while their flexible spines allowed for quick directional changes. This agility made them incredibly effective ambush predators, able to strike from below or behind with devastating surprise attacks.

Swimming dinosaurs, even the most aquatic-adapted like Spinosaurus, were fundamentally constrained by their terrestrial body plans. While they could move efficiently through water, they lacked the fine-tuned hydrodynamics that made mosasaurs such formidable aquatic predators.

Hunting Strategies: Evolved vs. Adapted

The difference between a born killer and an occasional swimmer becomes crystal clear when examining hunting strategies. Mosasaurs were ambush predators that perfected the art of underwater stalking, using their excellent vision to track prey before launching lightning-fast attacks from below.

These marine reptiles could hold their breath for extended periods, allowing them to remain motionless near the surface before striking upward at unsuspecting prey. Their attacks were calculated and precise, designed to incapacitate prey quickly and efficiently in an environment where a prolonged struggle could be fatal.

Swimming dinosaurs, by contrast, were opportunistic when it came to aquatic hunting. Spinosaurus likely waded through shallow waters, using its long snout to snatch fish and other prey—a strategy that worked well against smaller targets but would be disastrous against a predator specifically evolved to rule the depths.

Environmental Advantages: Home Field Dominance

In any contest between mosasaurs and swimming dinosaurs, the location of the encounter would be crucial. Mosasaurs held an overwhelming advantage in deep water, where their superior swimming abilities and underwater combat experience would prove decisive.

The deeper the water, the more pronounced this advantage became. Mosasaurs could dive to significant depths, attack from multiple angles, and use the three-dimensional nature of the aquatic environment to their advantage. They were equally comfortable attacking from above, below, or the sides—a tactical flexibility that land-adapted dinosaurs simply couldn’t match.

Even in shallow water, mosasaurs retained significant advantages. Their ability to remain submerged while maintaining visual contact with potential prey or threats gave them the element of surprise, while their powerful tails provided superior propulsion even in relatively confined spaces.

Defensive Capabilities: Built for Battle

When it came to defensive abilities, mosasaurs were living fortresses designed to withstand the rigors of marine combat. Their thick, scaly skin protected the sharp teeth of other marine predators, while their robust bone structure could absorb tremendous impacts.

More importantly, mosasaurs possessed the defensive advantage of mobility. In water, they could quickly retreat to deeper areas, use their superior speed to avoid attacks, or position themselves for counter-strikes. Their flexible bodies allowed them to twist and turn in ways that would be impossible for more rigid dinosaur body plans.

Swimming dinosaurs, while often well-armored on land, lost many of their defensive advantages in water. Heavy armor became a liability in aquatic environments, reducing speed and maneuverability while providing little protection against the crushing bite of a mosasaur.

Sensory Superiority: The Eyes Have It

One of the most overlooked aspects of the mosasaur’s advantage was its superior sensory equipment. These marine reptiles evolved exceptional vision both above and below water, allowing them to track prey and threats with remarkable accuracy.

Their eyes were positioned for maximum field of vision, and their brains were wired for rapid processing of visual information in the constantly changing aquatic environment. This sensory superiority meant that mosasaurs could detect approaching threats or opportunities long before their opponents were aware of their presence.

Additionally, mosasaurs likely possessed enhanced chemoreception abilities, allowing them to detect chemical traces in the water—essentially “tasting” their environment to locate prey or avoid larger predators. This gave them a significant intelligence-gathering advantage over dinosaurs that relied primarily on terrestrial senses.

The Spinosaurus Exception: A Worthy Opponent

While most swimming dinosaurs would be overmatched by mosasaurs, Spinosaurus presents a unique case study. Recent discoveries have revealed that this massive predator was far more aquatic than previously thought, with dense bones, paddle-like feet, and a lifestyle centered around rivers and coastal waters.

At 50+ feet in length and weighing up to 20 tons, Spinosaurus was one of the few dinosaurs that could potentially match a large mosasaur in terms of sheer size. Its massive claws and powerful limbs could deliver devastating attacks, while its crocodile-like skull was well-suited for aquatic combat.

However, even Spinosaurus would likely struggle against a mosasaur in deep water. The dinosaur’s advantages lay in shallow, riverine environments where it could use its powerful limbs for leverage and its size for intimidation. In the open ocean, where mosasaurs reigned supreme, even this formidable predator would be at a severe disadvantage.

Ecological Impact: Rulers of Different Realms

The dominance of mosasaurs in marine environments had profound ecological implications for any dinosaurs that ventured into the water. These marine reptiles essentially created a barrier that prevented most dinosaurs from fully exploiting aquatic niches.

This aquatic dominance meant that dinosaurs remained primarily terrestrial creatures, with only a few species developing semi-aquatic lifestyles. The presence of such formidable marine predators likely influenced dinosaur evolution, discouraging the development of fully aquatic dinosaur species.

The mosasaur reign of terror in the oceans lasted until the end-Cretaceous extinction event, demonstrating their remarkable success as marine predators. Their dominance was so complete that they faced little competition from other large marine reptiles, let alone occasional swimming dinosaurs.

Fossil Evidence: Battle Scars Tell the Story

While direct evidence of mosasaur-dinosaur combat is rare, fossil evidence provides tantalizing clues about these ancient encounters. Mosasaur fossils often show evidence of intense battles, with bite marks, broken bones, and healed injuries that speak to a life of constant combat.

Some of the most compelling evidence comes from bite marks on other marine reptiles and even other mosasaurs, demonstrating the incredible power of these predators’ jaws. The consistency and severity of these injuries suggest that mosasaurs were capable of inflicting devastating damage on any creature unfortunate enough to encounter them in the water.

Conversely, swimming dinosaur fossils rarely show evidence of marine predator attacks, possibly because encounters were so one-sided that few dinosaurs survived to tell the tale. The absence of evidence can sometimes be as telling as its presence when it comes to understanding ancient predator-prey relationships.

Modern Analogies: Lessons from Today’s Oceans

To understand the likely outcome of mosasaur-dinosaur encounters, we can look to modern marine ecosystems for guidance. Today’s apex marine predators—great white sharks, orcas, and saltwater crocodiles—demonstrate the overwhelming advantage that specialized aquatic hunters possess over terrestrial animals in water.

When large land mammals like elephants or bears enter the water, they become vulnerable to attacks from marine predators despite their size and strength on land. The same principle would apply to swimming dinosaurs facing mosasaurs—the aquatic environment fundamentally shifts the balance of power in favor of the marine specialist.

This modern parallel suggests that even the largest and most powerful swimming dinosaurs would be at a severe disadvantage when facing mosasaurs in their natural element. The evolutionary arms race between predator and prey in marine environments has consistently favored specialized aquatic hunters over terrestrial interlopers.

The Verdict: Ocean Supremacy

After examining the evidence from multiple angles, the answer to whether mosasaurs could defeat any dinosaur that swam becomes clear: in most aquatic encounters, the mosasaur would emerge victorious. Their superior size, specialized anatomy, crushing bite force, and millions of years of marine evolution gave them insurmountable advantages over even the most aquatic dinosaurs.

The few exceptions might occur in very shallow water environments where large dinosaurs like Spinosaurus could leverage their size and terrestrial adaptations effectively. However, these would be rare scenarios, and even then, the outcome would be far from certain.

The mosasaurs’ dominance in ancient seas was so complete that they essentially created an aquatic glass ceiling for dinosaur evolution. Their reign demonstrates the power of specialization in evolution—when it comes to ruling the oceans, there’s no substitute for millions of years of marine adaptation. What would you have guessed about these ancient underwater battles?