The final moments of Earth’s most magnificent creatures weren’t captured by cameras or recorded in history books. Instead, they were etched into stone—preserved in fossil records that tell stories more dramatic than any Hollywood blockbuster. These ancient remains hold secrets about catastrophic events, desperate survival attempts, and the ultimate extinction that ended 165 million years of dinosaur dominance.

The Asteroid Impact Theory Written in Stone

The most compelling evidence for the asteroid impact theory lies buried in a thin layer of rock called the K-Pg boundary. This geological marker, found worldwide, contains unusually high concentrations of iridium—a rare element on Earth but common in asteroids. The layer tells a story of global devastation that occurred approximately 66 million years ago.

Fossil evidence from this period reveals a sudden disappearance of non-avian dinosaurs, with their remains abruptly ending at this boundary layer. Scientists have discovered shocked quartz crystals and tiny glass spheres called tektites within these sediments, providing smoking gun evidence of an extraterrestrial impact. The Chicxulub crater in Mexico, measuring 150 kilometers across, serves as the ground zero for this cosmic catastrophe.

Mass Graves Tell Tales of Panic

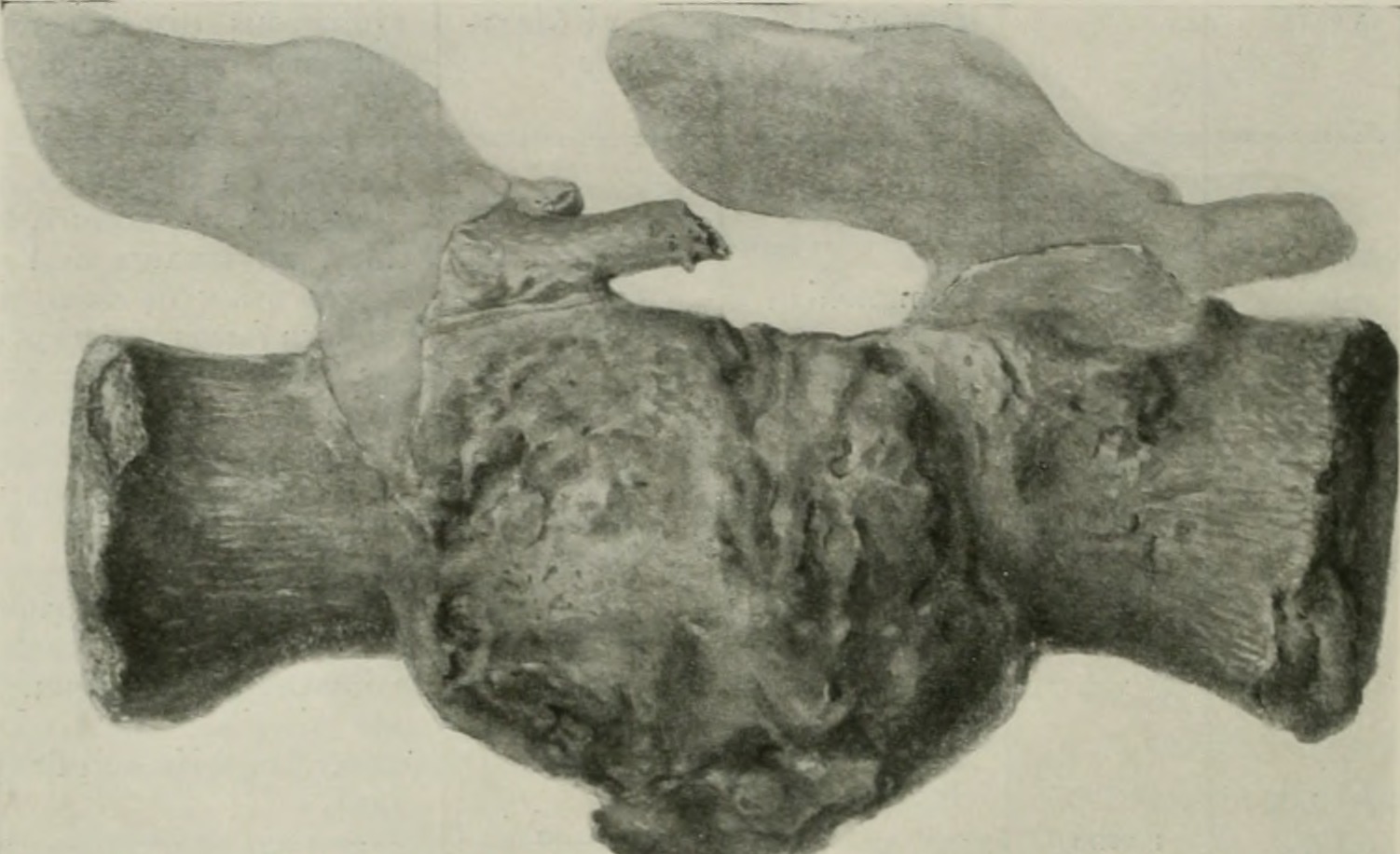

Some of the most haunting fossil discoveries come from mass burial sites where multiple dinosaurs died together. The famous “Fighting Dinosaurs” fossil from Mongolia captures a Velociraptor and Protoceratops locked in eternal combat, suggesting they were buried alive during a sudden sandstorm. These specimens provide snapshots of dinosaur behavior during their final moments.

In Montana’s Hell Creek Formation, paleontologists have uncovered bone beds containing hundreds of Triceratops and Edmontosaurus specimens. The chaotic arrangement of these fossils suggests rapid burial events, possibly caused by massive floods or debris flows triggered by the asteroid impact. These mass graves paint a picture of desperate herds fleeing from unprecedented environmental chaos.

Volcanic Eruptions: The Slow Burn Before the End

Long before the asteroid delivered its final blow, Earth was already experiencing one of its most violent volcanic episodes. The Deccan Traps in India were erupting continuously for over 30,000 years, spewing massive amounts of lava, ash, and toxic gases into the atmosphere. Fossil evidence from this period shows signs of environmental stress in dinosaur populations.

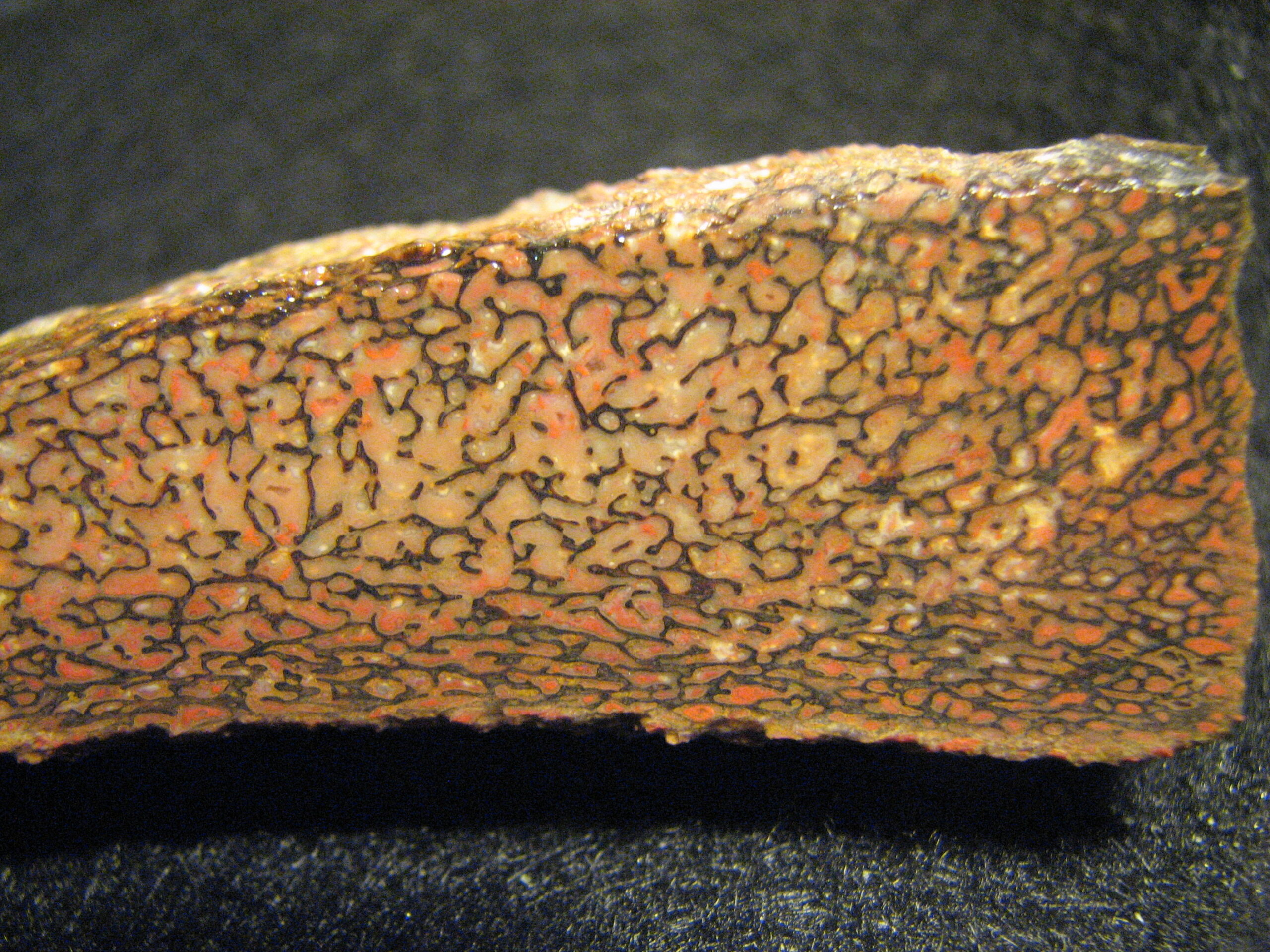

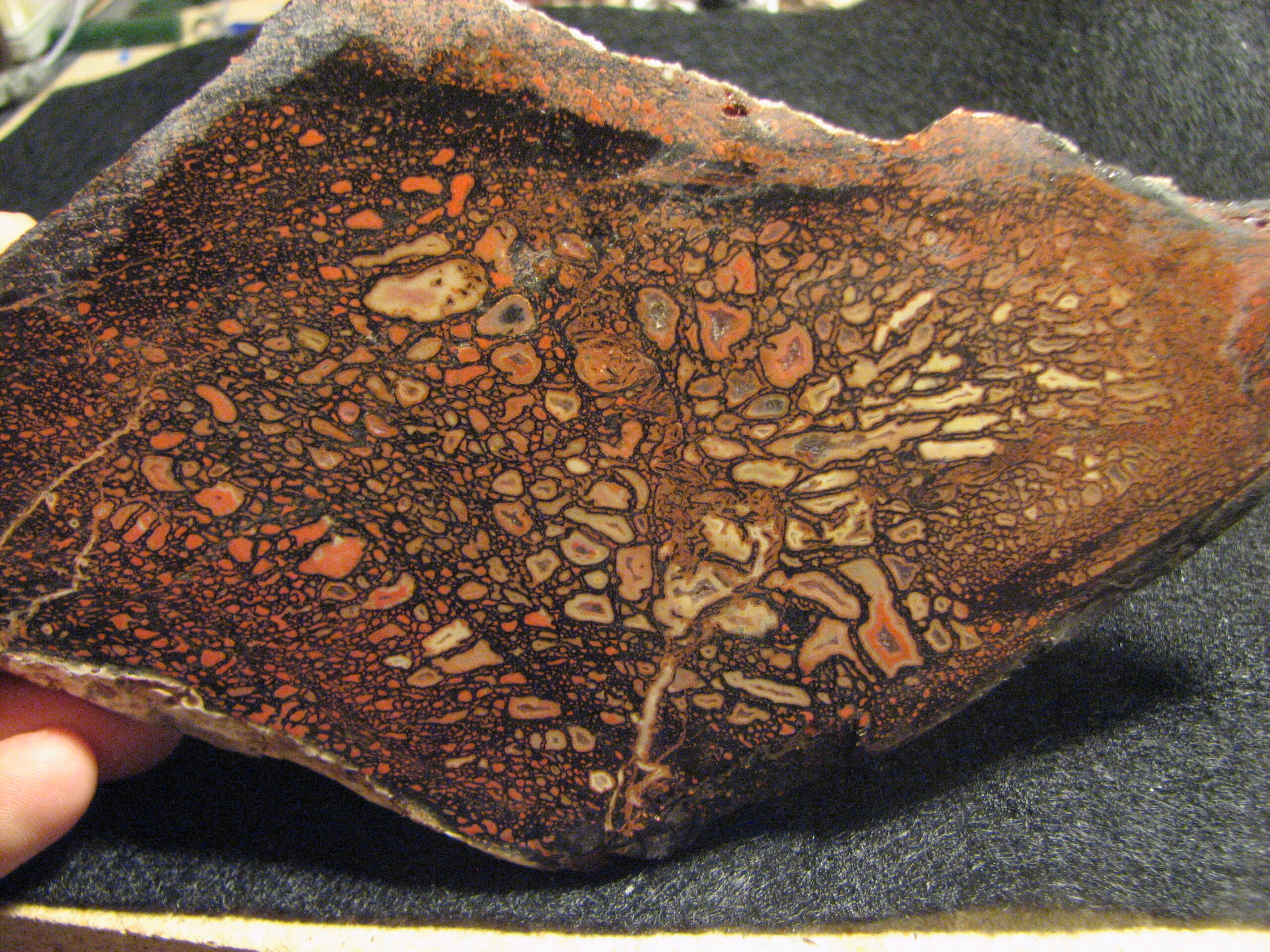

Dinosaur eggshells from the late Cretaceous period reveal abnormally thin walls and unusual crystal structures, suggesting that volcanic emissions were affecting calcium metabolism in these creatures. The changing chemistry of ancient soils, preserved in the geological record, indicates that acid rain and atmospheric poisoning were already weakening ecosystems. This volcanic activity may have set the stage for the asteroid impact to deliver its devastating knockout punch.

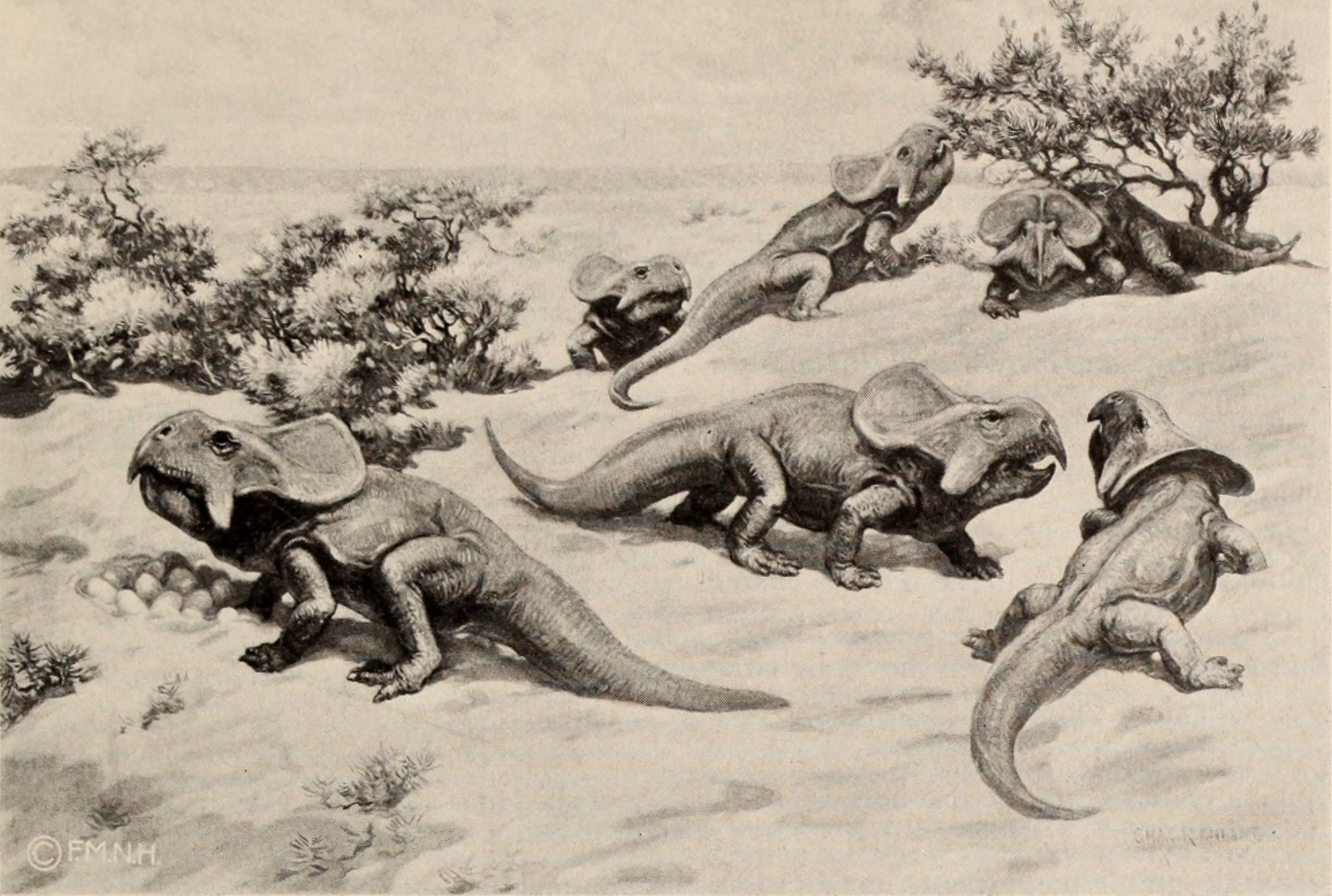

The Last Dinosaur Nests: Desperate Reproduction

Perhaps the most poignant fossil evidence comes from the final dinosaur nesting sites. In France’s Aix-en-Provence region, paleontologists discovered numerous Hypselosaurus eggs that never hatched, their embryos frozen in time within their calcified shells. These nests represent the last generation of dinosaurs that would never see the world beyond their eggs.

The fossilized embryos show various stages of development, from early cell division to nearly fully formed hatchlings. Some eggs contain evidence of bacterial infections, suggesting that environmental stress was already affecting reproductive success. These discoveries reveal that dinosaur parents continued their age-old rituals of nest-building and egg-laying even as their world was collapsing around them.

Evidence of Starvation and Disease

Pathological fossils from the late Cretaceous period provide disturbing evidence of widespread illness among dinosaur populations. Bone infections, malformed vertebrae, and signs of malnutrition appear with increasing frequency in fossils from this era. The famous “Sue,” a T. rex specimen, shows evidence of multiple infections and injuries that may have weakened her immune system.

Coprolites—fossilized dinosaur droppings—reveal changes in diet and digestion during the final period. These specimens contain unusual amounts of undigested plant material and parasites, suggesting that food sources were becoming scarce or contaminated. The presence of bone fragments in herbivore coprolites indicates that some plant-eaters were desperately consuming anything available, even resorting to chewing bones for calcium.

Forest Fires Preserved in Amber

Amber deposits from the end-Cretaceous period contain microscopic evidence of massive wildfires that swept across continents. These fossilized tree resins preserve charcoal particles, burned plant material, and even the remains of insects that died fleeing the flames. The amber record suggests that global fires raged for months after the asteroid impact.

Some amber specimens contain dinosaur feathers that show signs of heat damage, indicating that even flying dinosaurs couldn’t escape the infernos. The chemical composition of these preserved organics reveals that fires reached temperatures exceeding 1,000 degrees Celsius. This evidence supports the theory that the asteroid impact triggered a global firestorm that consumed much of Earth’s vegetation.

Ocean Acidification Recorded in Marine Fossils

While land-dwelling dinosaurs faced fire and darkness, marine environments were experiencing their own catastrophe. Fossil shells from the end-Cretaceous period show signs of severe dissolution, indicating that ocean acidity levels skyrocketed during this time. This acidification would have disrupted the marine food chain that many dinosaurs depended upon.

Ammonite fossils—spiral-shelled marine creatures—reveal increasingly malformed shells and stunted growth patterns near the extinction boundary. These deformities suggest that marine creatures were struggling to maintain their calcium carbonate shells in increasingly acidic waters. The collapse of marine ecosystems would have eliminated crucial food sources for coastal dinosaur populations.

Flash-Frozen Moments of Terror

Some of the most extraordinary fossil discoveries capture dinosaurs in their final moments with cinematic clarity. The “Sleeping Dragon” fossil from China shows a small dinosaur in a classic sleeping position, its head tucked under its arm like a modern bird. This peaceful pose contrasts starkly with the violent death that preserved it instantly.

In North Dakota’s Tanis site, researchers have uncovered fossils of fish with impact spherules still lodged in their gills—evidence that they died within hours of the asteroid impact. Mixed among these marine fossils are dinosaur bones, suggesting that the impact’s effects reached inland areas almost immediately. These discoveries provide a timeline of the extinction event measured in hours rather than years.

Surviving Species: The Lucky Few

Not all dinosaur lineages perished in the extinction event. Bird fossils from just after the K-Pg boundary reveal that smaller, more adaptable dinosaurs managed to survive the initial catastrophe. These early birds likely survived by feeding on seeds and insects, food sources that remained available even in the post-impact wasteland.

Fossil evidence suggests that ground-dwelling, seed-eating birds had significant advantages over their larger, more specialized relatives. Their ability to enter torpor—a state of reduced metabolic activity—may have helped them survive periods of extreme cold and food scarcity. These survivors would eventually evolve into the 10,000 bird species we see today.

The Nuclear Winter Effect in Geological Records

Sediment cores from around the world preserve evidence of the “impact winter” that followed the asteroid collision. These geological records show a sudden drop in temperature indicators and a dramatic decrease in photosynthetic activity. Plant fossils become increasingly rare above the K-Pg boundary, suggesting that primary productivity collapsed worldwide.

The isotopic composition of ancient soils indicates that temperatures dropped by as much as 10 degrees Celsius in some regions. This cooling effect, combined with the lack of sunlight, would have been devastating for large, warm-blooded dinosaurs with high metabolic requirements. Smaller animals with lower energy needs had a better chance of surviving the prolonged environmental crisis.

Chemical Signatures of Atmospheric Chaos

The chemical composition of rocks from the extinction boundary reveals the toxic cocktail that poisoned Earth’s atmosphere. High concentrations of sulfur compounds suggest that the asteroid impact vaporized massive amounts of sulfur-rich rocks, creating acid rain that persisted for years. These chemical signatures paint a picture of an atmosphere that became hostile to most life forms.

Nitrogen isotope ratios in fossil plants indicate that atmospheric chemistry was severely disrupted during this period. The data suggests that normal nitrogen cycling—essential for plant growth—was interrupted for decades after the impact. This chemical chaos would have prevented ecosystems from recovering quickly, prolonging the extinction event far beyond the initial impact.

Final Footprints: The Last Tracks

Some of the most emotionally powerful fossil evidence comes from the final dinosaur footprints preserved in ancient sediments. These trackways, found in locations like Spain and France, show the last movements of dinosaur communities before their extinction. The tracks reveal normal behavior patterns—feeding, walking, and social interactions—right up until the boundary layer.

One particularly poignant discovery in Colorado shows a series of sauropod tracks that suddenly end at a volcanic ash layer, suggesting that these gentle giants were walking normally when disaster struck. The preservation of these final moments provides an intimate connection to the last dinosaurs, making their extinction feel more personal and immediate.

Lessons from the Fossil Record

The fossil evidence of dinosaur extinction serves as a powerful reminder of life’s fragility in the face of catastrophic events. These ancient remains demonstrate how quickly dominant species can disappear when faced with rapid environmental changes. The extinction of dinosaurs wasn’t just about a single asteroid impact—it was about the cascading effects of multiple environmental stressors.

Modern climate change research draws heavily on lessons learned from the K-Pg extinction event. The fossil record shows that ecosystems can collapse rapidly when pushed beyond their limits, and recovery can take millions of years. Understanding these ancient catastrophes helps scientists predict how current species might respond to ongoing environmental changes.

The Ongoing Mystery

Despite decades of research, dinosaur fossils continue to reveal new secrets about their final days. Recent discoveries of soft tissue preservation, including proteins and DNA fragments, are providing unprecedented insights into the biology of these ancient creatures. Each new fossil discovery adds another piece to the puzzle of what happened 66 million years ago.

The story written in stone reminds us that even the most successful species can face sudden extinction when confronted with overwhelming environmental challenges. These fossilized testimonies from Earth’s past continue to shape our understanding of evolution, extinction, and the delicate balance that sustains life on our planet. What other secrets might these ancient witnesses still be hiding in the rocks beneath our feet?