The Tyrannosaurus rex stands as one of the most fearsome predators ever to walk the Earth, dominating the late Cretaceous landscape approximately 68-66 million years ago. With its massive jaws capable of delivering bone-crushing bites, powerful hind legs, and reputation as the “tyrant lizard king,” T. rex has long captured our imagination as the ultimate prehistoric predator. However, the dinosaur world was filled with numerous formidable creatures, many with their own specialized weapons and defenses. This raises an intriguing question that has fascinated paleontologists and dinosaur enthusiasts alike: Could any dinosaur have successfully challenged and defeated a T. rex in combat? By examining the physical attributes, hunting strategies, and defensive capabilities of various dinosaur species, we can explore this fascinating theoretical matchup.

The Remarkable Adaptations of T. Rex

Before exploring potential challengers, it’s important to understand what made T. rex such a formidable opponent. Adult T. rex specimens reached lengths of up to 40 feet and weights exceeding 9 tons, placing them among the largest land predators ever to exist. Their bite force has been estimated at up to 12,800 pounds, powerful enough to crush bones and tear through thick hide with ease. T. rex possessed binocular vision providing depth perception crucial for hunting, and recent research suggests they may have been more agile than previously thought, capable of turning relatively quickly despite their size. Their intelligence, based on brain-to-body ratios, indicates they were among the smarter dinosaurs, potentially able to use strategy when hunting or fighting. These combined attributes made T. rex an apex predator with few natural threats in its ecosystem.

Spinosaurus: The Water-Dwelling Giant

Spinosaurus aegyptiacus presents perhaps the most intriguing potential challenger to T. rex, as it exceeded the tyrant king in length at up to 50-59 feet. This semi-aquatic predator from North Africa possessed a distinctive sail on its back and specialized adaptations for fishing, including a crocodile-like snout filled with conical teeth ideal for grasping slippery prey. However, recent fossil evidence suggests Spinosaurus had relatively weak hind legs and spent much of its time in water, potentially making it less maneuverable on land compared to T. rex. A theoretical confrontation might favor Spinosaurus in or near water, where its swimming adaptations would give it a decisive advantage, allowing it to outmaneuver the less aquatically-adapted T. rex. On land, however, T. rex’s stronger bite force and more powerful legs would likely give it the upper hand in direct combat.

Giganotosaurus: The Heavyweight Contender

Giganotosaurus carolinii roamed South America approximately 98 million years ago and represents one of the most formidable potential rivals to T. rex. Slightly longer than T. rex at approximately 43 feet, though likely comparable in weight, Giganotosaurus had a slightly different hunting approach with its narrower skull and blade-like teeth designed for slicing rather than crushing. While its bite force was probably not as powerful as T. rex’s bone-crushing jaws, Giganotosaurus may have compensated with slightly longer arms, giving it marginally better grasping ability. The outcome of a theoretical confrontation would likely depend on the environment and circumstances, with Giganotosaurus possibly having a slight speed advantage but T. rex maintaining superior bite force. Many paleontologists suggest these evenly matched titans might result in a standoff, with neither having a decisive advantage over the other.

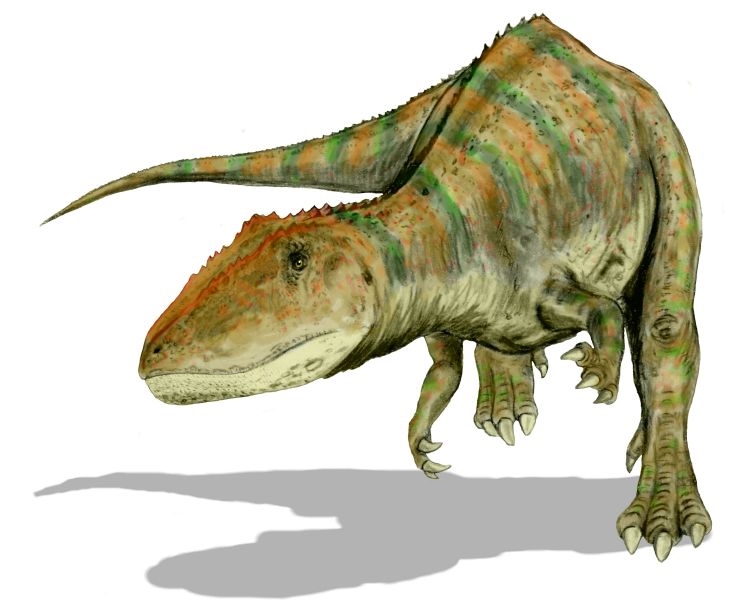

Carcharodontosaurus: The Shark-Toothed Giant

Carcharodontosaurus saharicus, whose name means “shark-toothed lizard,” was another massive theropod that inhabited North Africa during the middle Cretaceous period, about 100-94 million years ago. Similar in size to both T. rex and Giganotosaurus, this predator possessed serrated teeth up to eight inches long, designed for slicing through flesh with surgical precision. Carcharodontosaurus had a longer, narrower skull than T. rex, suggesting a different hunting strategy that potentially relied more on quick, slashing attacks rather than the bone-crushing bite of T. rex. In a hypothetical confrontation, Carcharodontosaurus might have employed hit-and-run tactics, using its potentially greater speed to deliver slashing wounds while avoiding direct confrontation. However, if T. rex managed to land its powerful bite, the fight would likely tilt decisively in the tyrant king’s favor, as its stronger jaws could inflict more devastating damage.

Triceratops: The Defensive Specialist

As one of T. rex’s actual contemporaries in Late Cretaceous North America, Triceratops horridus represents a fascinating potential opponent that evolved specifically with defensive capabilities. Armed with three formidable horns—two massive ones above the eyes and a shorter one on the nose—and a solid bone frill protecting its neck, Triceratops evolved these features likely as a defense against predators like T. rex. Weighing up to 12 tons, Triceratops was actually heavier than its predatory counterpart and could potentially use its low center of gravity to charge like a modern rhinoceros. Fossil evidence suggests T. rex and Triceratops did indeed engage in combat, with some Triceratops specimens showing healed bite marks consistent with T. rex attacks. In a defensive situation where the Triceratops could prepare for the encounter, its horns might have presented a serious deterrent, potentially capable of inflicting fatal wounds to even the mighty T. rex if the predator weren’t careful in its approach.

Ankylosaurus: The Armored Tank

Ankylosaurus magniventris represents perhaps the most heavily armored dinosaur that could have encountered T. rex, as both lived in North America during the late Cretaceous period. This herbivore’s entire body was covered in osteoderms—bone plates embedded in the skin—creating a natural armor that would have been extremely difficult for even T. rex’s powerful jaws to penetrate. The most formidable weapon in Ankylosaurus’s arsenal was its tail club, a massive bony growth that could be swung with tremendous force, potentially breaking the bones of any attacker. Recent studies suggest this tail club could generate forces strong enough to break the leg bones of large predators, creating a devastating defensive capability. In a confrontation, T. rex would need to flip or somehow access the softer underbelly of Ankylosaurus to inflict serious damage, a challenging task given the low-slung posture and massive weight of the armored dinosaur, which could exceed 8 tons.

Therizinosaurus: The Clawed Enigma

Therizinosaurus cheloniformis presents one of the strangest potential adversaries for T. rex, though these dinosaurs lived in different regions during the Late Cretaceous. This unusual theropod evolved to become a plant-eater but retained truly extraordinary weapons: forearms with claws reaching up to 3.3 feet in length—the longest claws of any known animal. Standing potentially 15-19 feet tall and weighing around 5 tons, Therizinosaurus could theoretically have used these massive claws as both defensive and offensive weapons. While not built primarily for combat, these claws could potentially deliver devastating slashing attacks against a predator like T. rex. However, Therizinosaurus lacked the specialized bite force and predatory instincts of T. rex, and without armor, it would be vulnerable to the tyrant’s powerful bite. The outcome would likely depend on whether Therizinosaurus could keep T. rex at bay with its massive claws long enough to inflict serious damage.

Mapusaurus: The Pack Hunter Advantage

Mapusaurus roseae offers a different kind of challenge to T. rex’s supremacy, not through individual size but through potential pack-hunting behavior. This South American theropod, closely related to Giganotosaurus, reached lengths of approximately 40 feet and weighed around 3-5 tons. What makes Mapusaurus particularly interesting is that fossil evidence suggests these carnivores may have hunted in packs, with multiple bone beds containing various individuals of different ages discovered together. While a single Mapusaurus might not defeat a full-grown T. rex in one-on-one combat, a coordinated pack of these large predators could potentially overwhelm even the mighty tyrant king through tactics and numerical advantage. This represents a different kind of threat—not from superior individual fighting capability but from cooperative hunting strategies that few other large theropods seem to have employed.

The Size Factor: Argentinosaurus and Other Massive Sauropods

The largest known dinosaurs, massive sauropods like Argentinosaurus huinculensis, represent a different kind of challenge based primarily on sheer size. Estimated to reach lengths of over 100 feet and weights potentially exceeding 70 tons, these herbivorous giants would have dwarfed even the largest T. rex. While not built for fighting and lacking specialized defensive weapons, their enormous size alone would make them difficult targets for any predator. An adult Argentinosaurus could potentially have used its massive tail as a whip or simply crushed an attacking T. rex with its enormous weight. The incredible size disparity would mean that even a successful bite from T. rex might not be enough to bring down such a massive animal quickly. However, young or weakened sauropods would still be vulnerable, and fossil evidence suggests large theropods did occasionally target these giants, particularly when they could isolate vulnerable individuals.

Utahraptor: Intelligence and Pack Tactics

Utahraptor ostrommaysi, while significantly smaller than T. rex at approximately 23 feet in length and 1,500 pounds, represents a fascinating theoretical opponent because of its specialized weapons and potential pack-hunting behavior. Living about 125 million years ago in North America (earlier than T. rex), Utahraptor possessed a sickle-shaped killing claw on each foot reaching nearly 15 inches in length, capable of delivering devastating slashing wounds. What makes Utahraptors particularly dangerous is the evidence suggesting they hunted in coordinated packs, using intelligence and teamwork to bring down prey much larger than themselves. A pack of these predators could potentially use distraction tactics to attack a T. rex from multiple angles simultaneously, targeting vulnerable areas while avoiding its powerful jaws. While individual Utahraptors would be quickly dispatched by T. rex, a coordinated pack might have presented a genuine threat even to the tyrant king.

Tarbosaurus: The Asian Counterpart

Tarbosaurus bataar serves as an interesting comparison to T. rex as it was essentially the Asian equivalent to the North American tyrant, living in what is now Mongolia during the same late Cretaceous period. Slightly smaller than T. rex but sharing many of the same adaptations, Tarbosaurus had a similarly powerful bite force, massive skull, and strong hind limbs optimized for hunting large prey. The primary differences between these close relatives were Tarbosaurus’s slightly narrower skull and smaller forelimbs. In a hypothetical confrontation between these two apex predators, the outcome would likely be determined by individual size and experience, with neither having a significant evolutionary advantage over the other. Both possessed nearly identical hunting adaptations, making this perhaps the most evenly matched potential battle, with the slightly larger size of T. rex potentially giving it a small edge in direct combat.

The Environmental Context: Terrain and Climate Considerations

Any theoretical dinosaur confrontation would be heavily influenced by the environment in which it took place, as different species evolved adaptations for specific habitats. T. rex thrived in the warm, semi-arid environments of late Cretaceous North America, with fossil evidence suggesting it hunted in both open plains and forested regions. A battle in water would dramatically favor semi-aquatic predators like Spinosaurus, whose paddling tail and specialized adaptations would give it superior mobility. Similarly, dense jungle environments might benefit more agile theropods that could maneuver between trees, potentially limiting T. rex’s ability to utilize its speed and powerful bite. Open terrain would generally favor T. rex’s hunting style, allowing it to use its binocular vision to spot prey from a distance and engage in relatively straight pursuit. The climate would also play a role, as some dinosaurs were adapted to specific temperature ranges, potentially affecting stamina and performance in confrontations outside their preferred environmental conditions.

Perspective on Dinosaur Combat: The Reality Beyond Popular Imagination

While entertaining to contemplate, it’s important to recognize that dinosaurs—like modern animals—likely engaged in actual combat only when necessary, typically avoiding high-risk confrontations that could result in serious injury. Predators like T. rex would have primarily targeted vulnerable prey rather than engaging equally dangerous competitors. Most confrontations between large carnivores in nature involve displays and posturing rather than fights to the death, with actual physical combat being relatively rare and usually brief. This pattern is observed in modern apex predators like lions, tigers, and crocodiles, which typically avoid potentially injurious fights with equal competitors whenever possible. The fossil record occasionally shows evidence of dinosaur combat, including healed bite marks and defensive wounds, but these likely represent exceptional rather than routine encounters. The theoretical matchups discussed here should therefore be understood as extraordinary scenarios rather than regular occurrences in the Mesozoic world.

Conclusion: The Tyrant’s Reign

After examining the various potential challengers to T. rex’s fighting supremacy, it becomes clear that while several dinosaurs possessed specialized adaptations that could prove advantageous in certain circumstances, T. rex remained one of the most formidable fighting machines in dinosaur history. Its combination of massive size, bone-crushing bite force, intelligence, and sensory capabilities made it exceptionally well-adapted for combat and predation. Some dinosaurs like Triceratops and Ankylosaurus evolved specific defensive specializations that could potentially deter or even injure T. rex, while others like Spinosaurus might have held advantages in specific environments. Pack hunters like Mapusaurus or Utahraptor could potentially overcome T. rex through coordinated attacks, highlighting that fighting prowess involves more than just individual physical attributes. While the question of which dinosaur would win in combat captures our imagination, it reminds us of the incredible diversity of adaptations that evolved during the Mesozoic era, with each species specialized for particular ecological niches rather than simply for combat with other dinosaurs.