Picture this: a prehistoric time machine hidden beneath our feet, where creatures from millennia past lie perfectly preserved in nature’s own formaldehyde. Ancient swamps and bogs have become the ultimate keepers of secrets, maintaining incredible records of life that would otherwise vanish into dust. These waterlogged time capsules hold everything from human remains with visible facial features to ancient butter that’s technically still edible after thousands of years.

Nature’s Perfect Preservation System

Peat forms in wetland conditions, where flooding or stagnant water obstructs the flow of oxygen from the atmosphere, slowing the rate of decomposition, and when plant material does not fully decay in acidic and anaerobic conditions. Think of these environments as nature’s vacuum-sealed storage units, where the usual rules of decay simply don’t apply.

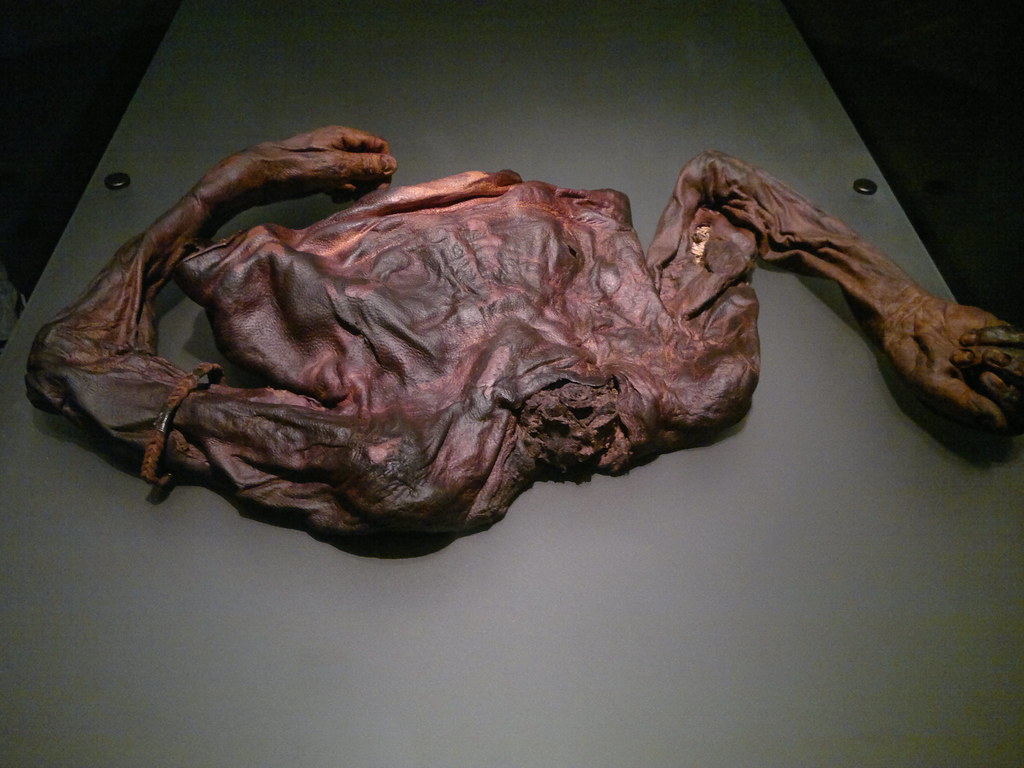

Bogs (cold-weather swamps) are excellent preservers of human bodies, with the oxygen-free environment preventing decay, and excessive tannins – naturally occurring chemicals used in tanning leather – preserve organic materials such as bodies, including the soft tissues and the contents of the digestive tract. It’s like an ancient pickling process that keeps everything from skin to stomach contents intact for researchers to study centuries later.

The Sphagnum Miracle Workers

Sphagnum mosses actively secrete tannins, which preserve organic material, and have special water-retaining cells, known as hyaline cells, which can release water ensuring the bogland remains constantly wet which helps promote peat production. These remarkable mosses don’t just grow in bogs – they literally create and maintain the perfect preservation conditions.

Sphagnan, a recently discovered polymer that seeps out of dead sphagnum moss, causes leather to be made through a process that strengthens the bonds between some of the natural fibers in animal hides, and as a tanning agent, sphagnan has the same effect on human skin, rendering it tough and tea-colored. The chemistry behind this preservation is so effective that scientists have successfully recreated it in laboratory settings.

Famous Faces from the Depths

The oldest bog body that has been identified is the Koelbjerg Man from Denmark, which has been dated to 8000 BC, during the Mesolithic period, while Tollund Man died sometime between 375-210 B.C., during the early Iron Age, and analysis revealed he was about 40 years old when he died. These individuals have become celebrities in the archaeological world, their faces as recognizable as any ancient pharaoh.

Some bog bodies are so well-preserved that scientists can still analyze the contents of their stomachs, revealing their last meals and offering insights into ancient diets, with Tollund Man having eaten a soup containing dozens of different seeds before he perished by hanging. It’s incredibly humbling to know what someone ate for their final meal over two thousand years ago.

Beyond Human Remains: A Treasure Trove of Artifacts

Butter is one of the objects archaeologists most frequently find in bogs, as people in northern Europe knew bogs had amazing preservative powers, and huge hunks of an edible waxy substance made of dairy or meat are sometimes found with these peat-bog men, with this “bog butter” potentially being a treasured food product to slather on Bronze Age bread. Imagine finding a chunk of butter that’s older than Christianity and discovering it’s still technically edible.

The biggest discovery ever to come out of a bog, by far, is the Corlea Trackway, a kilometer-long wooden road, built in Ireland in 148 BCE, which was a massive construction project, requiring at least 1000 wagon-loads of oak planks and birch rails, yet it would have been usable for only a few years, at most a decade, before sinking beneath the surface of the bog.

The Dark Chemistry of Preservation

As new peat replaces the old peat, the older material underneath rots and releases humic acid, also known as bog acid, with bog acids having pH levels similar to vinegar, preserving human bodies in the same way as fruit is preserved by pickling, in an environment that is highly acidic and devoid of oxygen. It’s essentially a natural embalming process that makes modern preservation techniques look primitive.

Sphagnan binds with nitrogen, which bacteria need to survive, so by removing nitrogen from the environment, sphagnan helps prevent the spread of microorganisms that would normally break down human and animal remains. This creates a hostile environment for decay organisms while keeping the organic matter intact.

Swamp Monsters and Ancient Ecosystems

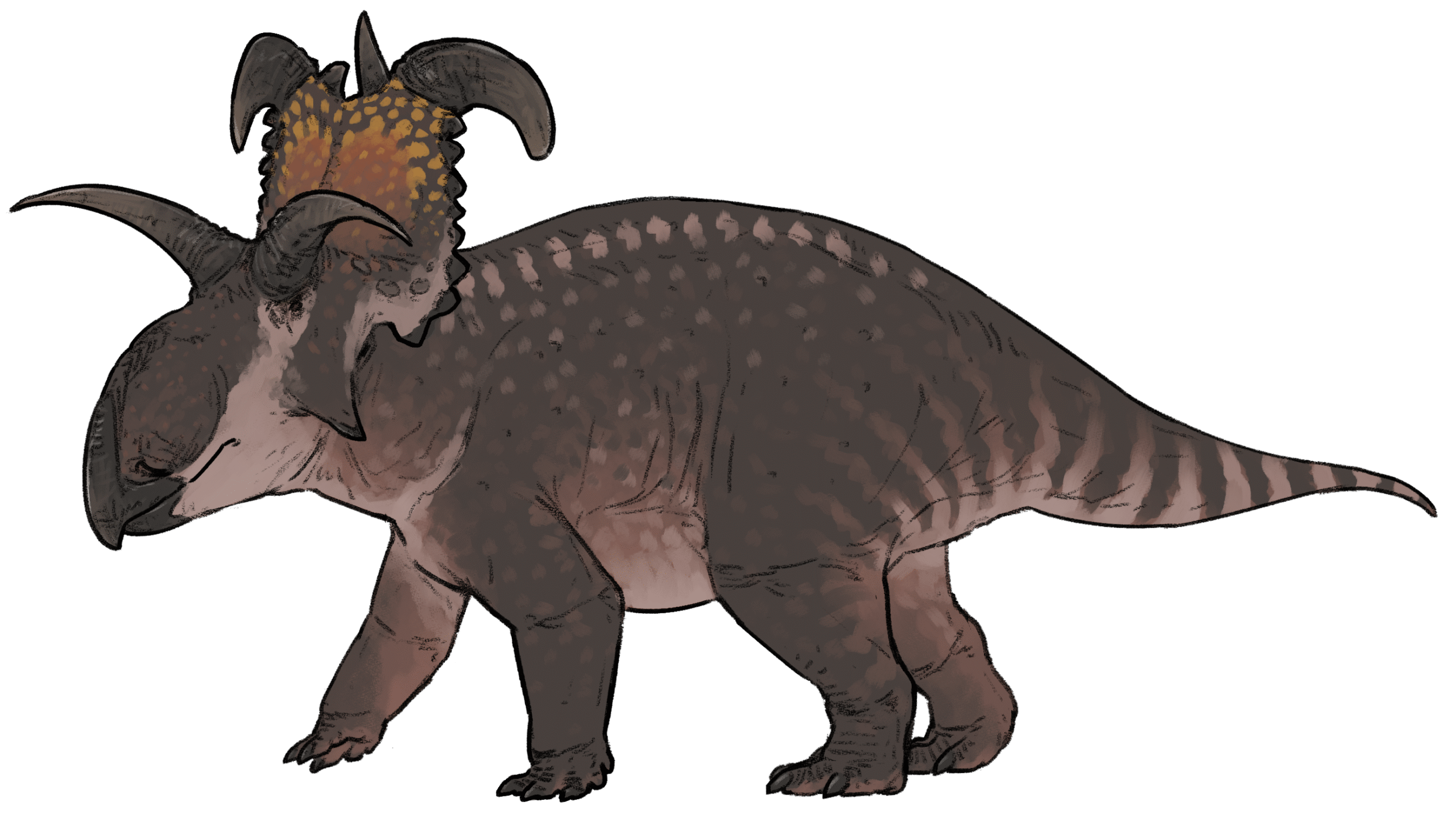

More than 78 million years ago, Lokiceratops inhabited the swamps and floodplains along the eastern shore of Laramidia, an island continent representing what is now the western part of North America created when a great seaway divided the continent around 100 million years ago, with mountain building and dramatic changes in climate and sea level altering this hothouse world. These ancient wetlands supported incredible diversity of life.

Over 300 million years ago, Illinois teemed with life in tropical swamps and seas, now preserved at the famous Mazon Creek fossil site. These prehistoric wetlands were bustling ecosystems teeming with creatures that we can still study thanks to exceptional preservation conditions.

The Windover Wonder: America’s Bog Body Bonanza

The Windover Bog has proven to be one of the most important archeological finds in the United States, discovered in 1982 when Steve Vanderjagt was using a backhoe to demuck the pond for development, getting out of his backhoe to investigate what he thought were rocks and almost immediately realizing that he had unearthed a huge pile of bones, calling the authorities right away. Talk about being in the right place at the right time.

The presence of brain matter in 91 of the bodies suggests that they were buried quickly, within 48 hours of death, as scientists know this because, given the hot humid climate of Florida, brains would have liquefied in bodies not buried quickly, and DNA analysis of the remains show that these bodies share no biological affiliation with the more modern Native American groups known to have lived in the area.

When Preservation Goes Wrong: The Race Against Time

The culprit is oxygen, as organic material trapped below the mossy surface of intact peat bogs is starved of oxygen, creating an environment too hostile for the fungi and bacteria that would normally break down plants or bones, but with excavation comes oxygen, which reacts with buried iron sulfide to produce sulfuric acid. Modern archaeological practices are actually threatening these natural time capsules.

The bones from the 2019 excavation were so weathered that their scoring system broke down, with some having lost more than half a centimeter of their outer layer, while other sections of the site where they expected to find remains yielded no bones at all, suggesting they had entirely decomposed. It’s a sobering reminder that these preservation conditions are more fragile than we once thought.

Bog Bodies and Ancient Mysteries

Many bog bodies died violently, with peat cutters in 2003 finding Oldcroghan Man and Clonycavan Man in two different bogs, both having lived between 400 and 175 B.C., and both having been subjected to a spectacular variety of depredations, including having their nipples mutilated. These weren’t accidental deaths but appear to be ritualistic killings that tell us about ancient societies’ darkest practices.

In rare instances, more than one body surfaces at once, with the Weerdinge couple, who are about 2,000 years old, not only discovered together, but sharing an intimate pose with one figure appearing to gently cradle the other smaller one, though follow-up research revealed that they were actually both male. These discoveries challenge our assumptions about ancient relationships and burial practices.

The Future of Bog Archaeology

The study is “sobering,” and demonstrates the “catastrophic loss of irreplaceable organic archaeological remains” in wetland sites across Europe, highlighting how important it is for researchers to better understand preservation and decay, with one archaeologist stating “We need to excavate now” because “If we wait 10 or 20 years, everything will be gone.” Climate change and human activity are rapidly destroying these natural archives.

The potential of bogs to preserve both environmental and archaeological records means that they can be regarded as archives of “hidden landscapes,” with the accumulating peat literally sealing and protecting evidence of human activity ranging from the macroscopic archaeological sites and artifacts to microscopic pollen and other remains that provide contextual evidence of environmental processes.

These ancient swamps and bogs continue to amaze us with their incredible preservation abilities and the secrets they reveal about our past. From perfectly preserved human faces to ancient butter still sitting in wooden kegs, these waterlogged time capsules offer us unparalleled glimpses into worlds that existed thousands of years ago. As we face the urgent challenge of studying these sites before they’re lost forever, each new discovery reminds us that sometimes the most extraordinary museums are hidden right beneath our feet in the muck and mire.