When you picture dinosaurs, you probably imagine them roaming through steaming jungles and lush swamps—not trudging through endless nights of snow and ice. But fossils tell a different story. Some dinosaurs lived in polar regions, where months of freezing darkness tested survival in ways we rarely imagine. How did these giants endure such extremes? Did they migrate to warmer lands, adapt their bodies to the cold, or even hibernate like animals do today? The clues scientists are uncovering may completely reshape what we think we know about life in the age of dinosaurs.

The Shocking Discovery of Polar Dinosaurs

Picture this: scientists digging in Alaska and Antarctica, expecting to find evidence of ancient warm climates, only to uncover something nobody saw coming. Dinosaur fossils have been found in Alaska, the South Pole, and parts of Australia that were functionally the South Pole back in the dinosaurs’ day. These weren’t just occasional visitors either. Scientists working in Australia, Alaska and even atop a mountain in Antarctica have unearthed remains of dinosaurs that prospered in environments that were cold for at least part of the year. Polar dinosaurs, as they are known, also had to endure prolonged darkness – up to six months each winter.

The implications were staggering. How could these supposedly cold-blooded reptiles survive where even modern animals struggle?

The Great Hibernation Debate That Shocked Scientists

For decades, paleontologists assumed they had it all figured out. Dinosaurs living in the intense cold and months-long darkness of the South Pole were once thought to hibernate during the winter months just to survive. It made perfect sense – if you can’t generate your own body heat, just sleep through the worst of it, right?

But then came Holly Woodward, a graduate student who decided to test this theory. Oklahoma State University graduate student Holly Woodward found that the physiology of dinosaurs living in Australia over 160 million years ago was practically the same as dinosaurs living everywhere else on Earth. Her research completely flipped our understanding on its head. Since the hibernation theory had been the primary theory for how these dinosaurs lived, Woodward inadvertently opened the door for new theories to take its place.

The Revolutionary Evidence Against Hibernation

Woodward’s breakthrough came from examining something you might never expect – dinosaur bones under a microscope. Paleontologists have used the growth rings within their bones to determine if dinosaurs hibernated or not. If the growth rings were more frequent in the bones of polar dinosaurs it would have indicated hibernation amongst these dinosaurs. Studies of Australian dinosaur bones indicated no such frequency, clearly showing that the polar dinosaurs stayed active year-round.

This was earth-shattering news. If polar dinosaurs weren’t hibernating, how on earth were they surviving those brutal winters? The evidence suggested something even more remarkable – these creatures were somehow staying active throughout the coldest, darkest months of the year.

The Feather Revolution: Nature’s Ultimate Winter Coat

Here’s where the story gets really fascinating. While we often think of feathers as being all about flight, their original purpose was probably much more practical. It has been suggested that feathers had originally functioned as thermal insulation, as it remains their function in the down feathers of infant birds prior to their eventual modification in birds into structures that support flight.

Recent discoveries have blown this theory wide open. Unlike other reptiles of the time, dinosaurs had warm coats of feathers. These could have helped the creatures weather short but intense cold spells after volcanic eruptions, the new study proposes. Scientists argue then that the fundamental evolutionary benefit of feathers is in keeping animals warm, with flight being only a secondary adaptation which came later. They further argue that dinosaurs must already have been adapted to cold weather, perhaps even living in environments with seasonal winters, in advance of the Triassic extinction.

Migration: The Ultimate Survival Journey

But not all dinosaurs could rely on feathers alone. Some species had a different strategy entirely – they packed up and moved. Edmontosaurus, from Alaska’s North Slope, is a better candidate for seasonal migration. Adults were about the size of elephants, so they would not have been able to crawl under rocks when temperatures fell. Rough calculations suggest that by ambling at about 1 mile per hour – “browsing speed” for animals of that size – herds of Edmontosaurus could have journeyed more than 1,000 kilometers.

However, this migration theory has some serious problems. A recently released study of northern and southern polar dinosaur migration indicates that some species may have migrated nearly 3,000 km in a six month period- far short of the distance needed to reach warmer climes. Dinosaurs would have had an even longer journey. Because the North Slope was much closer to the pole 70 million years ago, to escape the darkness, they would have had to walk 5,000 miles, nearly twice the distance from New York to Los Angeles.

The Burrowing Mystery: Underground Winter Hideouts

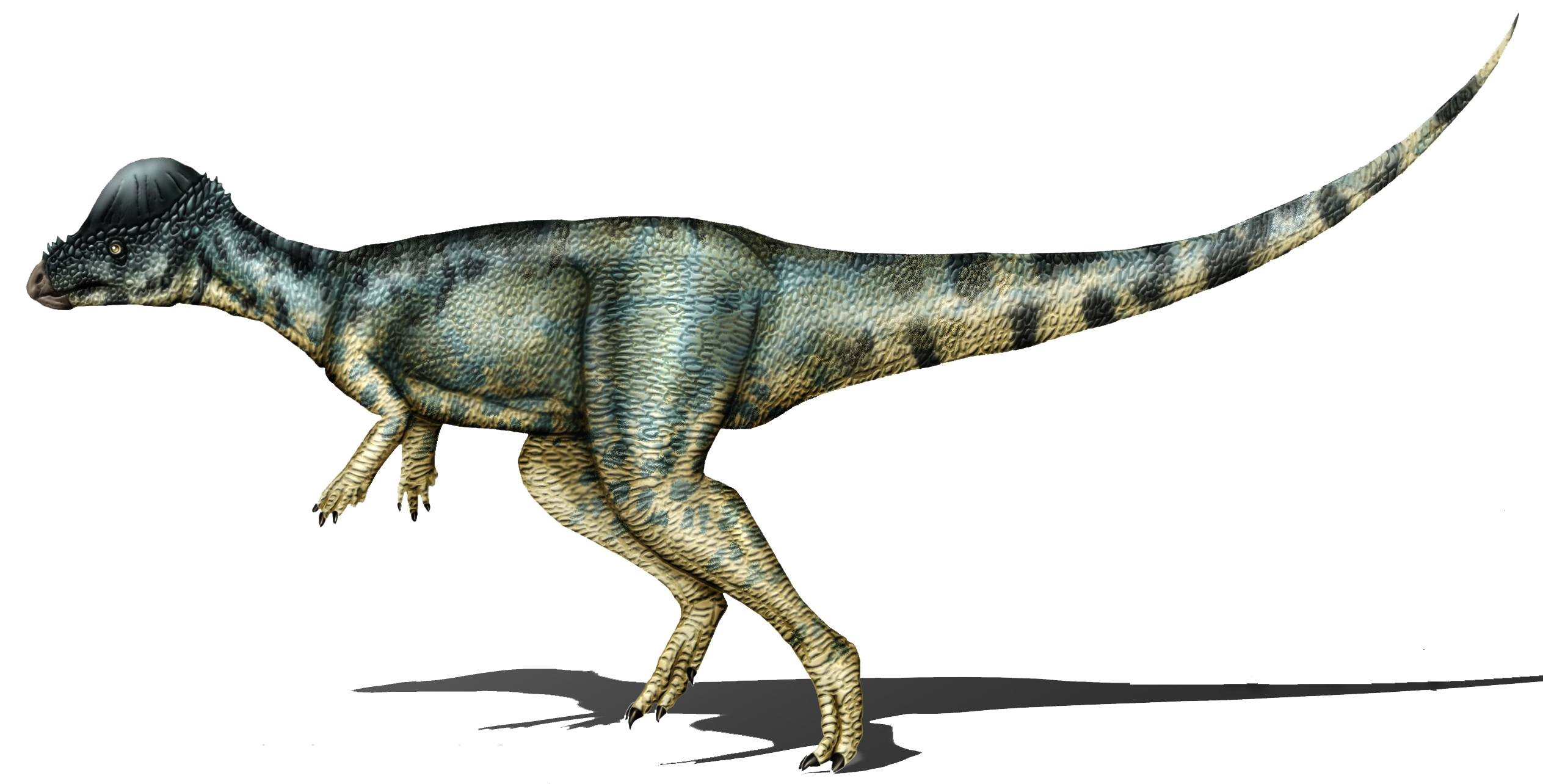

Sometimes the most surprising discoveries come from the most unexpected places. Some dinosaurs might have dug in to survive the harshest months. Paleontologists working in southern Australia’s strata have found burrow-like structures from the age of Leaellynasaura, and elsewhere these structures actually contain small, herbivorous dinosaurs. “It’s possible that dinosaurs might have burrowed as a way to escape the cold,” says paleontologist Adele Pentland of the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum of Natural History.

The evidence for dinosaur burrowing is pretty compelling. Internationally renowned palaeontologist and Monash University Honorary Research Associate, Dr Anthony Martin has found evidence of a dinosaur burrow along the coast of Victoria, which helps to explain how dinosaurs protected themselves from climate extremes during the Cretaceous period. Dr Martin made the discovery of the 2 metre-long burrow in 2006 while researching dinosaur tracks at Knowledge Creek, west of Melbourne.

The Warm-Blooded Revolution

Perhaps the most mind-blowing possibility is that we’ve had dinosaurs all wrong from the start. Previous research has found traits linked to warm-bloodedness among ornithischians and theropods, with some known to have had feathers or proto-feathers, insulating internal heat. First author Dr Alfio Alessandro Chiarenza, of UCL Earth Sciences, said: “Our analyses show that different climate preferences emerged among the main dinosaur groups around the time of the Jenkyns event 183 million years ago, when intense volcanic activity led to global warming and extinction of plant groups.”

This wasn’t just about surviving cold – it was about thriving in it. The adoption of endothermy, perhaps a result of this environmental crisis, may have enabled theropods and ornithischians to thrive in colder environments, allowing them to be highly active and sustain activity over longer periods, to develop and grow faster and produce more offspring.

Special Adaptations: Seeing in the Dark

Living through months of polar darkness required some pretty incredible adaptations. The prize discovery from Rich’s Dinosaur Cove excavation suggests that Leaellynasaura stayed active during the long polar winters. Rich found that the dinosaur had bulging optic lobes, parts of the brain that process visual information. Leaellynasaura’s optic lobes are larger than those from hypsis that lived in non-polar environments, suggesting that it had extra brainpower to analyze input from its big eyes.

This wasn’t unique to just one species either. Similarly, Fiorillo and Roland Gangloff, a retired paleontologist from the University of Alaska, have found that the small meat-eater Troodon was much more common on the North Slope of Alaska than farther south. Troodon might have gained an advantage over the other carnivorous dinosaurs in the north because it also had large eyes and a hefty brain, perhaps useful for hunting all winter long.

The Growth Pattern Mystery

One of the most surprising discoveries came from studying how polar dinosaurs actually grew during these harsh conditions. Much like their relatives elsewhere, polar dinosaurs grew fast when they were young but switched to more of a stop-and-start growth pattern as they got older. This means that polar dinosaurs were already biologically predisposed to surviving on less during the cold months, with the dinosaurs growing faster again during the lush summers.

This growth pattern was like having a built-in survival mechanism. Instead of hibernating completely, these dinosaurs could slow down their growth and metabolism when times were tough, then ramp back up when conditions improved.

The Ancient Hibernator That Changes Everything

While true dinosaurs might not have hibernated, there’s compelling evidence that some of their contemporaries did. New evidence suggests the Lystrosaurus species that lived before the dinosaurs evolved went into a state of hibernation to survive what is modern day Antarctica. They found prolonged stress consistent with animals that experience torpor, or prolonged rest such as hibernation, and it is the oldest instance of torpor known in fossil records. The scientists also believe that it may explain why the animal survived the mass extinction at the end of the Permian period, which wiped out about 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species.

This discovery is revolutionary because it shows hibernation-like behavior existed much earlier than we thought. The fossils are the oldest evidence of a hibernation-like state in a vertebrate animal, and indicate that torpor — a general term for hibernation and similar states in which animals temporarily lower their metabolic rates to get through a tough season — arose in vertebrates before mammals and dinosaurs evolved.

Why Some Dinosaurs Stayed Put Year-Round

The evidence for year-round polar residence is actually pretty strong. Various lines of evidence indicate that the dinosaurs remained in their home habitat through the winter. Just this past year, Fiorillo and colleagues were the ones who published on a jaw from a very young raptor – evidence that dinosaurs were nesting in the region and not just passing through.

Alaska’s dinosaurs had to contend with some of the same stresses as their southern counterparts – such as harsher changes in seasons and months of darkness – but evidence from their bones indicate that these dinosaurs stayed year-round. This means they developed incredible strategies to not just survive, but actually reproduce in these extreme conditions.

The Winter Survival Strategies That Actually Worked

So how did they actually make it through those brutal polar winters? The answer seems to be a combination of strategies. For larger, presumably non-hibernating megaherbivorous taxa such as hadrosaurids and ceratopsids, fasting was a possibility, as large size provides advantages over small taxa with regard to lower relative metabolic rates, surface to mass scaling advantages, and greater absolute reserves of somatic tissues that can be used for survival. It is also possible that the consumption of low-quality forage following the shedding of deciduous leaves (perhaps bark, ferns, horsetails, or moss) may have served as winter subsistence.

In the case of smaller taxa such as thescelosaurids and leptoceratopsids, hibernation or torpor was a possible strategy, potentially using burrows for both shelter during the winter and protection of young. Different sizes, different solutions – nature’s way of making sure everyone had a fighting chance.

Conclusion

The question of whether dinosaurs hibernated has led us down a fascinating rabbit hole of discovery. While most dinosaurs probably didn’t hibernate in the traditional sense, they developed an incredible array of survival strategies that are far more impressive than simply sleeping through the winter. From growing warm feather coats and developing super-powered night vision to digging underground burrows and potentially becoming warm-blooded, these ancient creatures were far more adaptable and sophisticated than we ever imagined.

The polar dinosaurs challenge everything we thought we knew about these magnificent creatures. They weren’t just giant lizards stumbling around tropical swamps – they were complex, highly adapted animals capable of thriving in some of the most challenging environments our planet has ever seen. Perhaps that’s the most remarkable discovery of all.

Did you expect dinosaurs to be such incredible survivors against all odds?