Picture this: a seemingly ordinary day in what is now Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, roughly sixty-six million years ago. The sun shines over lush tropical forests where massive T-rex hunt duck-billed dinosaurs, while long-necked sauropods graze peacefully nearby. Then, suddenly, a brilliant white dot appears in the sky, growing larger and brighter until it becomes an unstoppable force of destruction. What happened next would forever change the course of life on Earth, ending the reign of the dinosaurs and setting the stage for mammals – including eventually us – to take over the planet.

The Moment Everything Changed

The asteroid that sealed the dinosaurs’ fate was roughly six to ten miles wide and struck Earth at speeds exceeding 25 kilometers per second. That’s more than seventy times the speed of sound, creating an impact so violent it defies human comprehension. The collision released energy equivalent to 100 teratons of TNT – that’s 4.5 billion times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

The impact blasted a crater initially 100 kilometers wide and 30 kilometers deep, though the final Chicxulub crater measures about 200 kilometers in diameter. To put that in perspective, it’s larger than many U.S. states. The initial blast created superheated winds moving over 1,000 kilometers per hour that would have radiated outward for nearly 2,000 kilometers, instantly killing any creature unlucky enough to be in the open.

The Smoking Gun Discovery

For decades, scientists debated what caused the dinosaurs’ sudden disappearance. The breakthrough came in 1980 when physicist Luis Alvarez and his geologist son Walter proposed their revolutionary theory about an asteroid impact. Their evidence? A thin layer of clay found in Italy that contained unusually high levels of iridium, a rare metal on Earth but common in asteroids and comets.

The actual crater wasn’t discovered until the late 1970s by geophysicists Antonio Camargo and Glen Penfield, who were searching for oil reserves in the Yucatan Peninsula for Pemex. It took until the early 1990s for scientists to confirm that this buried structure was indeed the long-sought impact crater that coincided perfectly with the dinosaur extinction timeline.

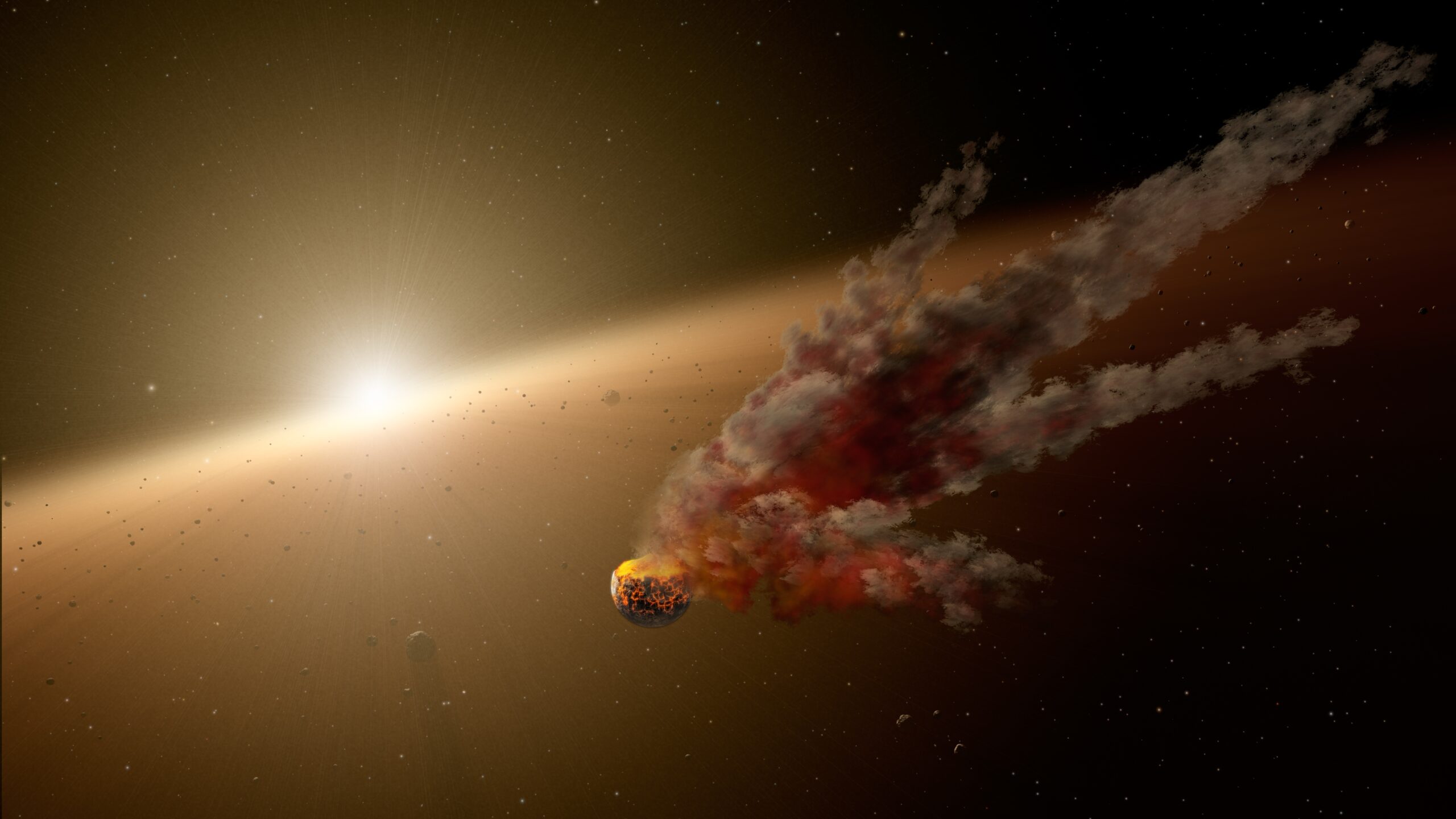

Death from Above: The Asteroid’s Origins

Scientists now believe the killer asteroid was a C-type carbonaceous chondrite that originally formed in the outer Solar System, beyond Jupiter’s orbit. These dark, organic-rich space rocks are rare visitors to Earth’s neighborhood, making this collision even more extraordinary. Recent chemical analysis of rock layers from around the world confirms that all the destruction came from a single extraterrestrial source, ruling out theories about massive volcanic eruptions being the primary cause.

Computer models suggest there was roughly a 60 percent probability that this particular asteroid originated from beyond 2.5 astronomical units from the Sun. It traveled millions of miles and billions of years through space before its fateful rendezvous with Earth, carrying within it the power to reshape life itself.

The First Day of Hell on Earth

Thanks to new analysis of core samples from the crater’s peak ring, scientists can now create a detailed timeline of what happened on that catastrophic day and in its immediate aftermath. The destruction unfolded in terrifying stages, each worse than the last.

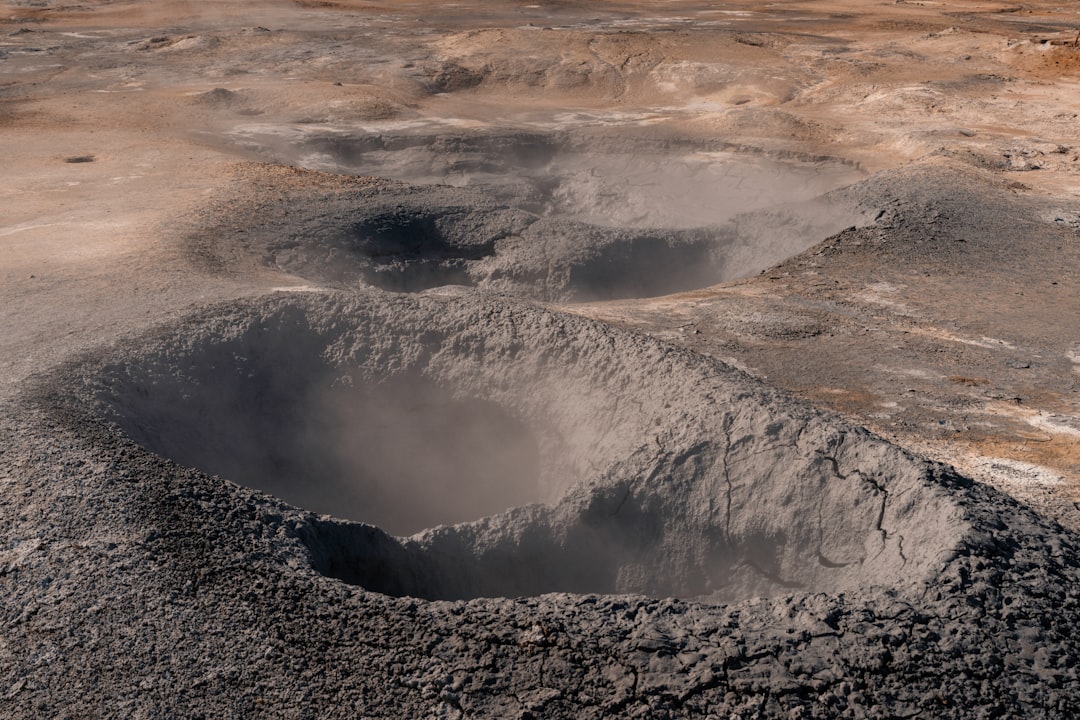

Within minutes of impact, the asteroid vaporized completely while deep granite bedrock flowed like liquid, rebounding into a central tower as tall as 10 kilometers before collapsing into the circular ridge we see today. This was quickly covered by jumbled-up rocks containing chunks of blasted material and impact melt, followed by massive tsunami deposits as ocean waters rushed into the giant hole. The peak ring formed almost instantly and was soon buried under more than 70 feet of additional rock that had melted in the heat of the blast.

When the Sun Disappeared

The immediate destruction was just the beginning of Earth’s nightmare. The impact ejected massive amounts of vaporized rock and debris into the atmosphere, creating a global dust cloud that blocked out the Sun for years or even decades. Soot traveled around the entire world, significantly reducing the amount of sunlight reaching Earth’s surface and devastating plant growth.

This created what scientists call an “impact winter” – a prolonged period of darkness and extreme cooling that made life nearly impossible for creatures accustomed to the warm, stable climate of the Late Cretaceous period. Surface temperatures plummeted by as much as 50 degrees Fahrenheit, creating a frozen wasteland that persisted for years. Imagine trying to survive in a world where summer never comes, where the sky remains dark, and where most plants simply die.

The Sulfur Connection: Why Location Mattered

What made this particular impact so devastating was its location – the asteroid struck a geologically unique, sulfur-rich region that amplified the destruction far beyond what would have occurred almost anywhere else on Earth. The Yucatan Peninsula in the Late Cretaceous was covered by warm, shallow seas overlying sulfur-rich carbonate rocks, and the impact vaporized enormous quantities of sulfur – estimated at more than 10 million times the mass of the Eiffel Tower – directly into the atmosphere.

This sulfur rapidly formed sulfate aerosols in the stratosphere, which reflected incoming solar radiation and caused additional cooling that lasted for many years. These sulfuric acid clouds, similar to those that permanently shroud Venus, may have blanketed Earth for more than a decade, creating a secondary and more long-lasting extinction event that proved to be the final blow for the dinosaurs.

The Great Dying: Who Lived and Who Died

The extinction was brutal in its scope – roughly 75 percent of all plant and animal species on Earth disappeared, including all non-avian dinosaurs. By some estimates, nearly 70 percent of species died off, making this one of the most severe extinction events in Earth’s history. Yet the pattern of survival reveals fascinating insights into what it takes to endure a global catastrophe.

The survivors shared key characteristics: omnivores, insectivores, and carrion-eaters made it through, likely because of the increased availability of their food sources, while neither strictly herbivorous nor strictly carnivorous mammals survived. The first hurdle rewarded specific characteristics – small body size and a burrowing or semi-aquatic lifestyle – and dinosaurs, for the most part, didn’t fit the bill. A devastating 93 percent of mammals died in the extinction, with survivors being smaller than most Cretaceous mammals and having generalist, omnivorous diets, while the victims were larger with more specialized diets.

The New World: Survivors and Their Stories

Birds were the only dinosaurs to survive, and their survival hinged on a crucial adaptation – beaks capable of crushing tough seeds allowed them to feed on the seeds of destroyed forests and wait out the decades until vegetation returned. While there are more than 18,000 bird species alive today, the ancestors of as few as five major bird lineages survived the extinction.

A surprising variety of other species also made it through, including frogs, snakes, lizards, alligators, crocodiles, and small mammals. Cold-blooded crocodiles survived because they have very limited food needs and can go months without eating, while warm-blooded animals of similar size need much more food to sustain their faster metabolism. All surviving species were plausibly able to take shelter from heat and fire underground or in water, giving them protection during the immediate aftermath.

The story of the Chicxulub impact isn’t just about death and destruction – it’s about resilience, adaptation, and the remarkable ability of life to recover from even the most catastrophic events. In the aftermath, mammals diversified rapidly in the Paleogene Period, evolving into horses, whales, bats, and primates, while the surviving dinosaurs radiated into all modern species of birds. Without that terrible day sixty-six million years ago, our world would look completely different. We owe our very existence to the survivors who endured when the sky fell, proving that sometimes the end of one age is merely the beginning of another. What would our planet be like if that asteroid had missed Earth entirely?