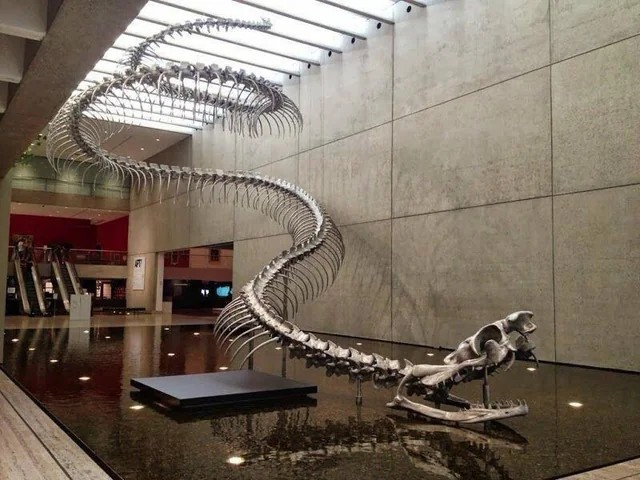

Picture this: you’re walking through the steamy jungles of ancient Colombia, sixty million years ago. The air is thick with humidity, the ground squelches beneath your feet, and then you see it – a serpentine shadow moving through the water. Not just any snake, but a creature so massive it makes today’s anacondas look like garden hoses. This is Titanoboa, the undisputed king of prehistoric snakes, and its story is one of the most remarkable discoveries in paleontology.

The Accidental Discovery That Changed Everything

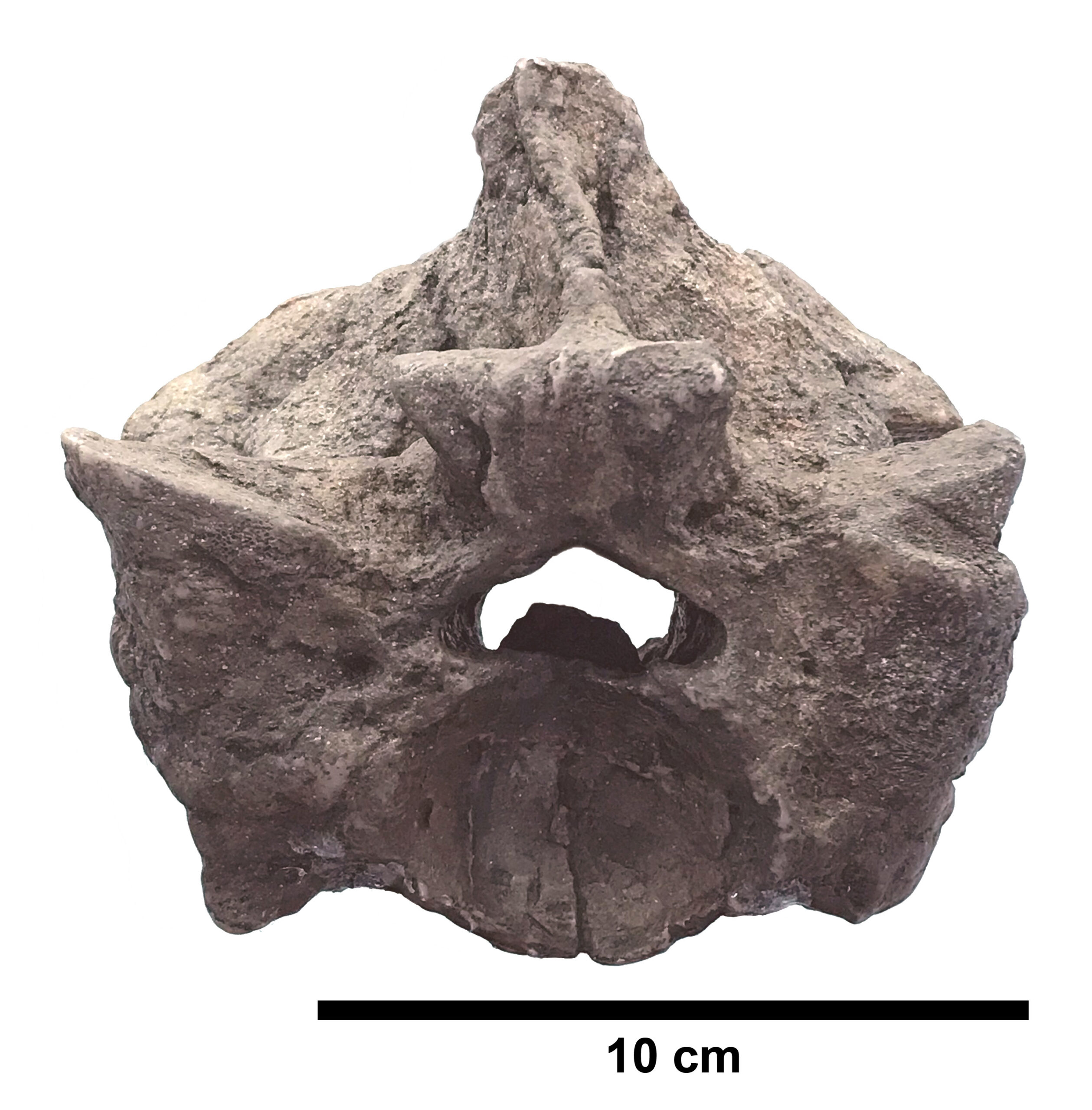

The search for the river monsters of the Paleocene Epoch began here by accident 18 years ago, when Colombian geologist Henry Garcia found an unfamiliar fossil. In 2002, during an expedition to the coal mines of Cerrejón in La Guajira launched by the University of Florida and Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, large thoracic vertebrae and ribs were unearthed by the students Jonathon Bloch and Carlos Jaramillo.

The expedition lasted until 2004, during which the fossils of Titanoboa were mistakenly labeled as those of crocodiles. The expedition lasted until 2004, during which the fossils of Titanoboa were mistakenly labeled as those of crocodiles. Nobody could have imagined that these mysterious bones would rewrite our understanding of prehistoric life.

Size Beyond Imagination: The Numbers That Stunned Scientists

When paleontologists finally recognized what they had found, the measurements were absolutely staggering. Using this method, initial size estimates proposed a total body length of approximately 12.82 m (42.1 ft). The team published its first results in Nature in early 2009, saying Titanoboa was between 42 feet and 49 feet long, with a mean weight of 2,500 pounds. Named Titanoboa cerrejonensis by its discoverers, the size of the snake’s vertebrae suggest it weighed 1140 kg (2,500 pounds) and measured 13 metres (42.7 feet) nose to tail tip.

At its greatest width, the snake would have come up to about your hips. The size is pretty amazing. To put this in perspective, imagine trying to fit through a doorway – this snake would have had to squeeze just to get through most office doors.

The Cerrejón Coal Mine: A Window Into Ancient Worlds

The discovery of that creature, an accidental discovery at that, happened in a giant open-pit coal mine in northwestern Colombia, about 60 miles from the coast. This mine is excavating thick coal seams from a geologic unit called the Cerrejón Formation, taking 32 million tons of coal from the ground each year, making it the largest coal mine in Latin America.

The fossils are usually below the coal seams so actually the mining uncovers the fossils for us; the mine is an ideal place to look for fossils. The big mining machines remove tons of coal and expose hundreds of square meters of rocks. It’s ironic that industrial mining operations would become the gateway to understanding life from sixty million years ago.

Ancient Climate: A Greenhouse World of Giants

Based on the relation between temperatures in the modern Neotropics and the maximum length of anacondas, Head and colleagues calculated a mean annual temperature of at least 32–33 °C (90–91 °F) for the equatorial region of Paleocene South America. Assuming the Earth today is not particularly unusual, Head and Dr Jonathan Bloch, Assistant Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Florida Museum of Natural History, estimated a snake of Titanoboa’s size would have required an average annual temperature of 30 to 34°C (86 to 93 F) to survive.

Titanoboa was a coldblooded animal whose body temperature depended on that of its habitat. Reptiles can grow bigger in warmer climates, where they can absorb enough energy to maintain a necessary metabolic rate. Think of it like a biological thermostat – the hotter the environment, the bigger these cold-blooded creatures could grow.

The Paleocene Ecosystem: A Lost World of Swamps

The coals mined at Cerrejón are formed from deposits left by an extensive Paleocene swamp situated along the margins of an ancient shallow sea, which sat at the base of the early precursors of the Andes Mountains. This ancient environment had been similar in composition to the swamps of the Mississippi River delta or Everglades in North America; however, it was situated in the tropics at a time when Earth’s climate was exceptionally warm.

The sedimentary structure of the region’s rocks and the preservation of water-loving organisms (such as mangrovelike plants, crocodilians, turtles, and fishes) as fossils in the strata indicate that the region was waterlogged. Titanoboa lived mostly under water in a large river system, in what is now known to be world’s oldest neotropical rainforest. This ecosystem had diverse flora and wildlife for giant snakes to prey on, such as turtles, crocodilians, birds, and mammals.

Hunting Strategies: The Ultimate Ambush Predator

Titanoboa was the apex predator of its time, ruling the prehistoric swamps with an iron grip. Its massive size and strength allowed it to take down virtually any creature it encountered. With no natural predators, it sat at the top of the food chain, dictating the balance of life in its ecosystem.

Its size and constricting ability would have been its primary hunting methods, similar to modern-day anacondas and boas. Titanoboa was a massive snake, and while capable of powerful movements, the claim of it reaching speeds of 50 mph is highly improbable and lacks scientific support. Its size would have made such speed impossible, and it likely relied on ambush tactics rather than high-speed pursuits. Picture a school bus-sized snake lying motionless in murky water, waiting for the perfect moment to strike.

Diet Mysteries: Fish-Eating Giant or Crocodile Crusher?

However, in the 2013 abstract, Jason Head and colleagues noted that the skull of this snake displays multiple adaptations to a piscivorous diet, including the anatomy of the palate, the tooth count, and the anatomy of the teeth themselves. These adaptations are not seen in other boids, but closely resemble those in modern caeonphidian snakes with a piscivorous diet.

Anatomically, the reptile’s teeth and jaws resemble those of modern snakes who specialize in eating fish. If the gargantuan snake followed suit, it was the only boid on record with a fish-centric diet. This finding surprised researchers who initially assumed Titanoboa would hunt like modern anacondas, crushing large prey in its coils.

The Skull Discovery: A Paleontological Jackpot

While on a field trip with five paleontologists in the Cerrejón coal mine in Colombia, geologist Gersom Garcia alerted Suarez Gomez and biologist Jorge Moreno to additional Titanoboa bones discovered on a walk. My heart started beating so fast. I could not believe what I was seeing.

These are skull fragments of a snake!’ he said. His smile was huge and he said: ‘Catalina, we found it. Finally….This is the skull of Titanoboa!'” Finding the skull of a snake is like looking for needle in a haystack as the bones are very small and do not hold together as a human skull does.

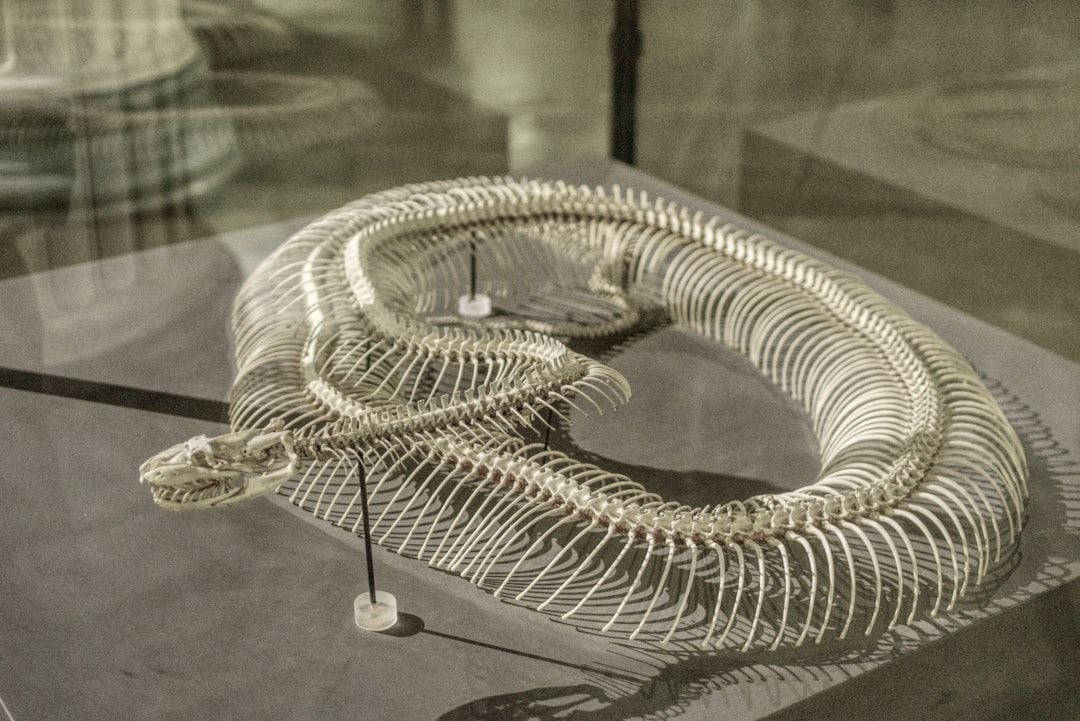

Comparing Giants: Titanoboa versus Modern Snakes

By comparison, adult anacondas average about 6.5 metres (21.3 feet) in length, whereas record-breaking anacondas are about 9 metres (about 29.5 feet) long. No living snake has ever been found with a verified length in excess of 9 metres (about 30 feet).

Titanoboa makes even the largest modern snakes seem diminutive in comparison. While today’s biggest snakes, like the green anaconda or reticulated python, can reach impressive lengths, they pale next to Titanoboa’s 40-foot stretch. This prehistoric giant was not only longer but also considerably bulkier, with a girth that could easily surpass any snake seen today. It’s like comparing a garden hose to a subway tunnel.

Living Habits: The Semi-Aquatic Lifestyle

Titanoboa probably spent much of its time in the water. Similarly, modern anacondas spend most of their time in or near the water, where they hide amid vegetation in the shallows and ambush prey.

Like the green anaconda, Titanoboa probably spent a great deal of time in bodies of water. There, it could easily lug its massive body weight around – and beat the jungle’s sweltering heat. Water provided both thermal regulation and the perfect hunting ground for this massive predator.

The Mystery of Extinction: When Giants Fell

The extinction of Titanoboa remains a tantalizing mystery. As the climate cooled, the warm conditions that supported its massive size began to disappear. This change likely led to a decline in suitable habitats and prey, contributing to its eventual extinction.

Titanoboa being so large has been taken as an indication that the planet had a higher average global temperature during the Paleocene than previously thought. It is also thought however that average global temperatures were very slowly declining something that is thought to have contributed towards a global shift from dense forests to open grasslands during later epochs going on towards the Miocene.

Scientific Legacy: What Titanoboa Teaches Us

Back in ’09, Head described the Titanoboa snake as a giant thermometer. Based on the discovery of Titanoboa, he developed a method to estimate past environmental temperatures from the reptile fossil record. This discovery revolutionized how scientists study ancient climates.

Its discovery not only provides us with a glimpse into Earth’s prehistoric ecosystems but also underscores the importance of understanding the relationship between climate and evolution. By studying these ancient creatures, we can better understand the forces that shaped life on Earth and how climate change can influence the evolution of species.

Conclusion

Titanoboa represents more than just a prehistoric monster – it’s a window into Earth’s ancient past and a testament to how dramatically climate can shape life on our planet. This thirteen-meter serpent ruled Colombian swamps during one of Earth’s hottest periods, creating an ecosystem unlike anything we see today. Its discovery has revolutionized our understanding of Paleocene climate conditions and showed us that nature’s capacity for producing giants far exceeds what we see in modern times.

The coal mines of Cerrejón continue to yield secrets, and each fossil adds another piece to the puzzle of this lost world. While Titanoboa itself is long extinct, its legacy lives on in the scientific insights it provides about evolution, climate, and the delicate balance of ecosystems. In a world facing rapid climate change, understanding how ancient creatures like Titanoboa responded to temperature shifts becomes more relevant than ever.

What would you have guessed about the size limits of prehistoric snakes before learning about this Colombian giant?