Walk into most museums and you’ll still find raptors displayed as sleek, scaly predators, frozen in the imagery popularized by Jurassic Park. But switch on a recent documentary or blockbuster, and suddenly those same raptors are bristling with feathers. So why the disconnect? The answer lies in the rapid pace of paleontological discovery—and the slower march of public display. While science has uncovered overwhelming evidence of feathered raptors, museums face challenges of tradition, cost, and visitor expectation. The result is a fascinating clash between pop culture, science, and the way we choose to picture the past.

The Hollywood Monster That Changed Everything

Picture this: you’re sitting in a darkened theater in 1993, watching as a pack of Velociraptor (commonly referred to as “raptor”) is one of the dinosaur genera most familiar to the general public due to its prominent role in the Jurassic Park films. These sleek, intelligent hunters stalk their prey with calculated precision, their scaled skin gleaming under the jungle moonlight. That iconic scene from Jurassic Park burned an image into millions of minds worldwide – an image that would prove remarkably resistant to change, even as science revealed a startling truth.

What audiences didn’t know then was that they were witnessing one of the biggest scientific misrepresentations in cinema history. Jurassic Park and its sequel The Lost World: Jurassic Park were released before the discovery that dromaeosaurs had feathers, so the Velociraptor in both films were depicted as scaled and featherless. The timing couldn’t have been worse for scientific accuracy – or better for creating a lasting cultural icon.

When Science Caught Up to Fiction

The dinosaur renaissance was already underway when Jurassic Park hit theaters, but the general public remained largely unaware of the revolutionary discoveries happening in paleontology labs. Dinosaurs have been getting slowly more birdlike for decades – perhaps not in mainstream depictions, but at least in the minds of paleontologists. The evidence was mounting that these “terrible lizards” were actually something far more fascinating – feathered, warm-blooded creatures more closely related to modern birds than cold-blooded reptiles.

By the time scientists definitively proved that raptors had feathers, Hollywood’s version had already taken root in popular culture. A new look at some old bones have shown that Velociraptor, the dinosaur made famous in the movie Jurassic Park, had feathers. A paper describing the discovery, made by paleontologists at the American Museum of Natural History and the Field Museum of Natural History, appears in the September 2007 issue of the journal Science.

The Museum Revolution That Hollywood Missed

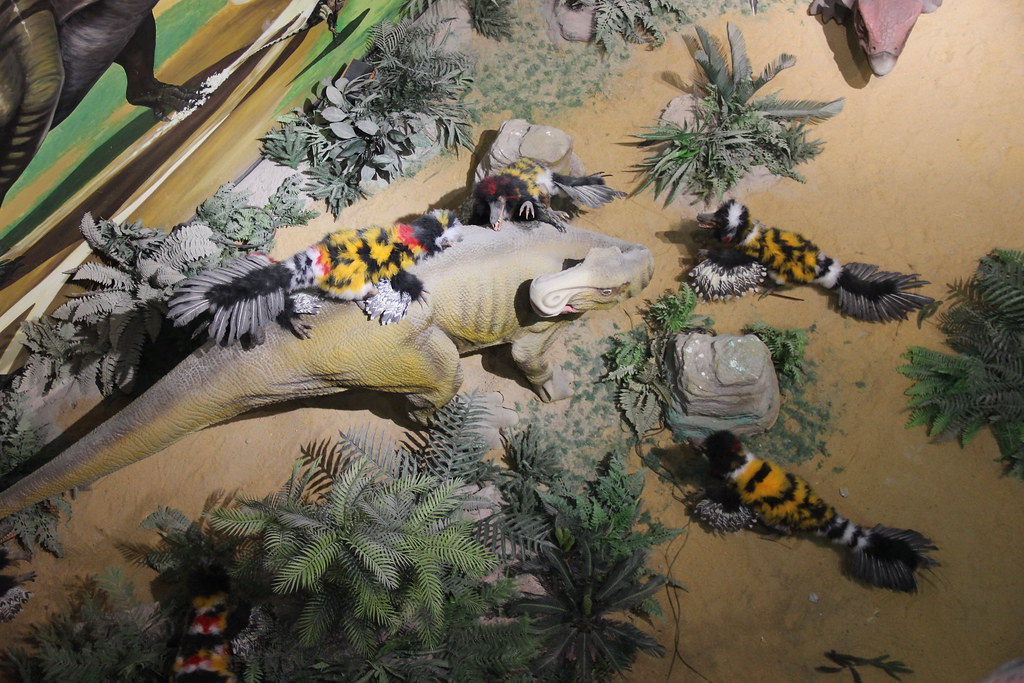

While movie studios continued churning out sequels featuring scaly raptors, museums began a quiet revolution. Following the latest evidence, all the dinosaurs on display are covered in feathers. “It’s really the first time dinosaurs have been portrayed in a true, state-of-the-art kind of way,” says Norell. The American Museum of Natural History’s “Dinosaurs Among Us” exhibit became a game-changer, finally giving the public a chance to see scientifically accurate dinosaurs.

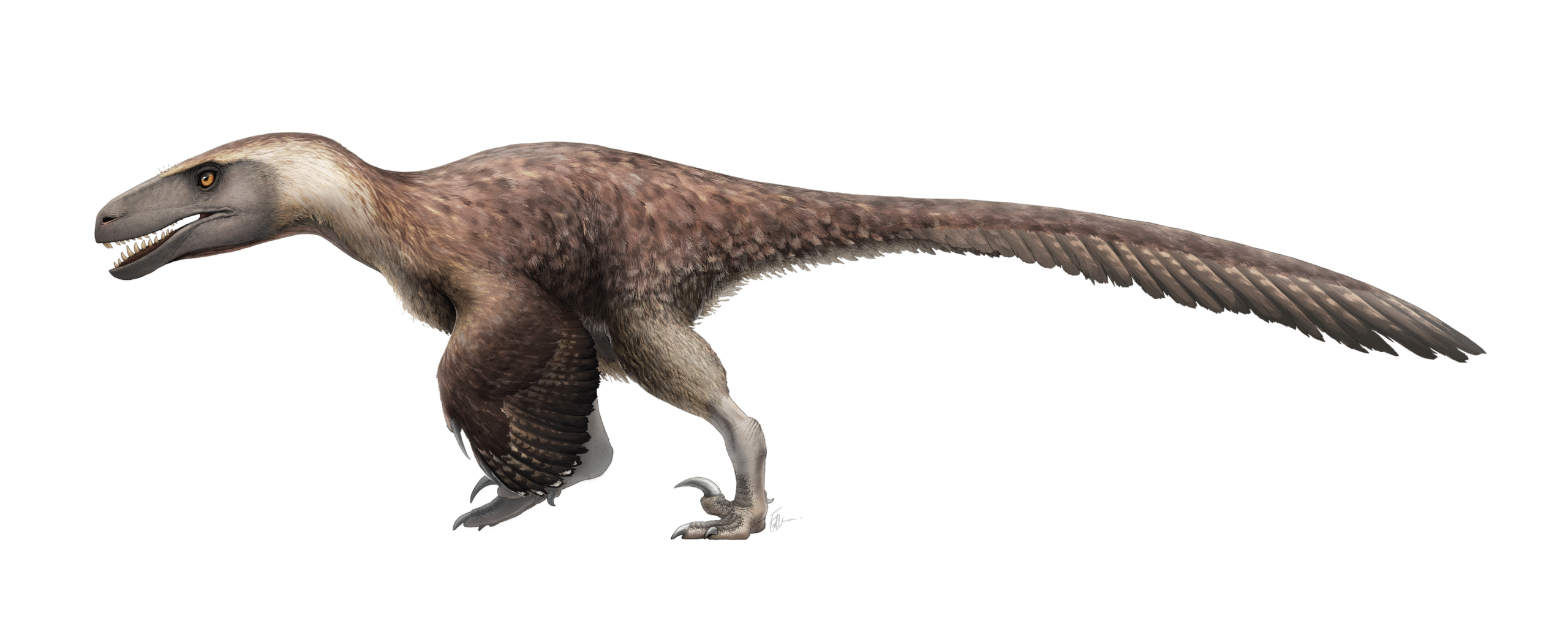

These new exhibits revealed creatures that looked radically different from their Hollywood counterparts. Instead of reptilian monsters, visitors encountered dinosaurs that resembled giant, exotic birds. Under Martyniuk’s pen, these are more than lizards with feathers drawn on them; Velociraptor mongoliensis really does resemble a roadrunner in its “jizz” (a birder’s expression for a bird’s characteristic overall look and behavior).

The Great Size Deception

Hollywood’s raptors weren’t just wrong about feathers – they were completely off about size too. Smaller than other dromaeosaurids like Deinonychus and Achillobator, Velociraptor was about 1.5–2.07 m (4.9–6.8 ft) long with a body mass around 14.1–19.7 kg (31–43 lb). In reality, these fearsome predators were roughly the size of a large turkey, not the human-sized monsters that terrorized moviegoers.

Museums had to work overtime to correct this misconception. One thing that was known about Raptors in 1993 was how large they were. While some of its relatives could grow quite large, Velociraptor itself was six feet long, and stood just under two feet tall at the hip. The movie versions were actually closer in size to Deinonychus, a different species entirely that lived in North America rather than Asia.

The Fossil Evidence That Changed Everything

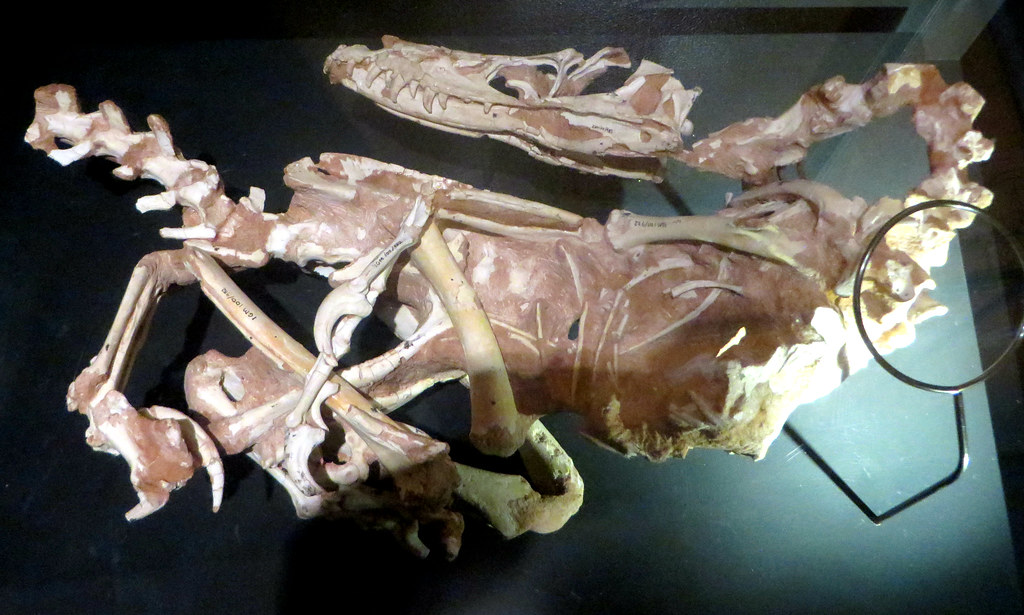

The breakthrough came from examining fossilized bones with fresh eyes. Scientists found evidence of six quill knobs–locations where feathers are anchored to bone–on the forearm of a Velociraptor fossil. They found on it clear indications of quill knobs “places where the quills of secondary feathers, the flight or wing feathers of modern birds, were anchored to the bone with ligaments. This wasn’t speculation anymore – it was hard, physical evidence that raptors had been feathered creatures.

The implications were staggering for paleontology. Mark Norell, Curator in the Division of Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History and coauthor on the study. “Both have wishbones, brooded their nests, possess hollow bones, and were covered in feathers. These weren’t just random similarities – they painted a picture of creatures that behaved more like modern birds than movie monsters.

Why Museums Embraced the Truth While Movies Resisted

The divergence between museums and movies wasn’t accidental – it reflected fundamentally different goals. Despite all this scientific consensus, pop culture might take a while to acknowledge the evolution of feathered dinosaurs, says Robert Bakker, curator of paleontology at the Houston Museum of Natural Science and one of the advisors for the 1993 film Jurassic Park. It’s simply easier, and perhaps scarier, to have scaly green dinosaurs, he says.

Museums, bound by scientific accuracy and educational missions, couldn’t ignore mounting evidence. Well, movie Raptors are often meant to be more scary than scientifically accurate, and a more reptilian Velociraptor plays up phobias that the general public tends to have of scaly things like snakes and alligators. Fear sells tickets; scientific accuracy doesn’t always pack theaters.

The Educational Battle Against Popular Culture

Museum educators found themselves fighting an uphill battle against decades of pop culture conditioning. Many paleontologists, museum designers, and educators have expressed the reality that the general audience is still largely ignorant that many dinosaurs had feathers even when educating about feathered genera known for decades by the 2020s; said audience often naming the Jurassic Park/World series as a direct reason for their confusion. Visitors would arrive expecting to see movie-accurate dinosaurs and leave confused by the scientific reality.

This created an ongoing challenge for science communication. Another reason is that it’s just plain hard to change peoples’ minds once a particular image is established in their heads, even though it’s been shown to be incorrect. Museums had to develop new strategies to help visitors understand that real science often contradicts Hollywood spectacle.

What Feathers Actually Did for Dinosaurs

The discovery of feathered dinosaurs revealed that these structures served many purposes beyond flight. Feathers are one of the most useful skin coverings that ever evolved. Feathers are one of the most useful skin coverings that ever evolved. They provided insulation, helped with courtship displays, and assisted in temperature regulation – functions that made these ancient creatures far more sophisticated than their movie counterparts suggested.

Research showed that even massive predators sported feathery coverings. The Yutyrannus, described in 2012, are the largest known dinosaurs with feathers – a patch of fossilized skin shows shaggy body feathers, similar to an Emu. Yutyrannus was related to T. rex and measured 30 feet long and weighed about 3,100 pounds. If something that large could have feathers, it changed everything scientists thought they knew about dinosaur biology.

The Technology That Finally Revealed the Truth

Advanced fossil preservation techniques and new analytical methods finally provided the evidence museums needed. Discoveries in the Liaoning Province of China, such as Sinornithosaurus, pictured above, have transformed our understanding of the transition from feathered dinosaurs to birds. Fossils from the region tend to be exquisitely well preserved, showing delicate features including feathers. These weren’t just impressions or guesswork – they were detailed, microscopic structures that left no doubt about dinosaur appearances.

Museums invested heavily in displaying these remarkable discoveries. According to an exhibit label, the museum’s preparators spent 1,300 hours preparing the fossil for display. They “revealed details – like skin imprints and tiny skull bones – that are not preserved in other Archaeopteryx fossils”. This level of detail allowed visitors to see for themselves what these ancient creatures actually looked like.

The Modern Museum Experience vs. Movie Magic

Today’s museum exhibits offer something movies never could – authentic scientific discovery in real time. The museum frequently updates its dinosaur exhibits with special displays that highlight new research and discoveries. Recent exhibitions have focused on the role of feathers in dinosaur evolution and featured newly discovered species. Visitors can witness paleontology in action, not just finished Hollywood products.

Interactive displays now help bridge the gap between expectation and reality. Museums use technology to show how feathered dinosaurs might have moved and behaved, giving visitors a more complete picture than static skeletons ever could. This approach helps overcome the “movie brain” syndrome that makes scientific accuracy harder to accept than familiar fiction.

Why Hollywood Still Hasn’t Caught Up

Despite overwhelming scientific evidence, the movie industry remains surprisingly resistant to change. While early designs for the first movie did incorporate some amount of feathers, these were dropped into for the sake of consistency with the books, the comparative ease of animating smooth, scaly bodies vs. plumage in early 1990s CGI, and desires by the film makers. Even today, with advanced CGI capabilities, filmmakers often choose familiar over accurate.

The few attempts to incorporate feathers have been half-hearted at best. The Jurassic World trilogy isn’t entirely featherless, but the plumage is greatly restricted and subdued. When feathers do appear, they’re minimal nods to science rather than comprehensive updates to reflect current knowledge.

The Future of Dinosaur Representation

Museums continue pushing boundaries while waiting for popular culture to catch up. Today, artist-scientists are ahead of both the public and the museums in visualizing the “new” dinosaurs. For example, Matthew Martyniuk’s cheeky Field Guide to Mesozoic Birds and Other Winged Dinosaurs is my favorite: a Peterson-style guide not only to birds like Archaeopteryx, but also birdlike dinosaurs. These innovative approaches help visitors reimagine dinosaurs as the complex, feathered creatures they actually were.

The gap between scientific knowledge and popular representation remains frustratingly wide, but museums are leading the charge toward accuracy. They’re betting that authentic wonder beats manufactured fear – that a feathered raptor is actually more amazing than a scaly monster. “That’s something we’re all waiting for – a Jurassic Park where there’s no more naked dinosaurs” remains the dream of paleontologists worldwide.

The truth is, museums got it right because they had to – their mission demands scientific accuracy over entertainment value. Movies chose spectacle over science, creating a cultural divide that persists today. While Hollywood raptors continue terrorizing audiences with their reptilian ferocity, museum visitors get to meet the real thing: magnificent feathered predators that were far more bird than monster. So next time you see a movie raptor, remember – the truth is actually much more extraordinary than fiction. Don’t you think that makes them even cooler?