When we think of the Jurassic, towering land giants like Brachiosaurus usually steal the spotlight—but beneath the waves, an entirely different cast of predators reigned. Sleek ichthyosaurs darted through the water like prehistoric dolphins, while long-necked plesiosaurs cruised the seas with a grace that belied their size. These marine reptiles weren’t dinosaurs, yet they were every bit as fierce and fascinating. Fossil evidence reveals oceans filled with hunters that rivaled their land-dwelling counterparts in power and adaptability. So, could these underwater titans truly compete with the dinosaurs ruling the land? The answer may surprise you.

The Ocean’s Hidden Giants

Imagine standing on the shores of ancient Europe, where most of what we now call Britain lay submerged beneath vast shallow seas. The land you’d be looking at would be nothing like today – just scattered islands where Scotland and parts of England peek above the waves. What’s really mind-blowing is what was lurking beneath those ancient waters.

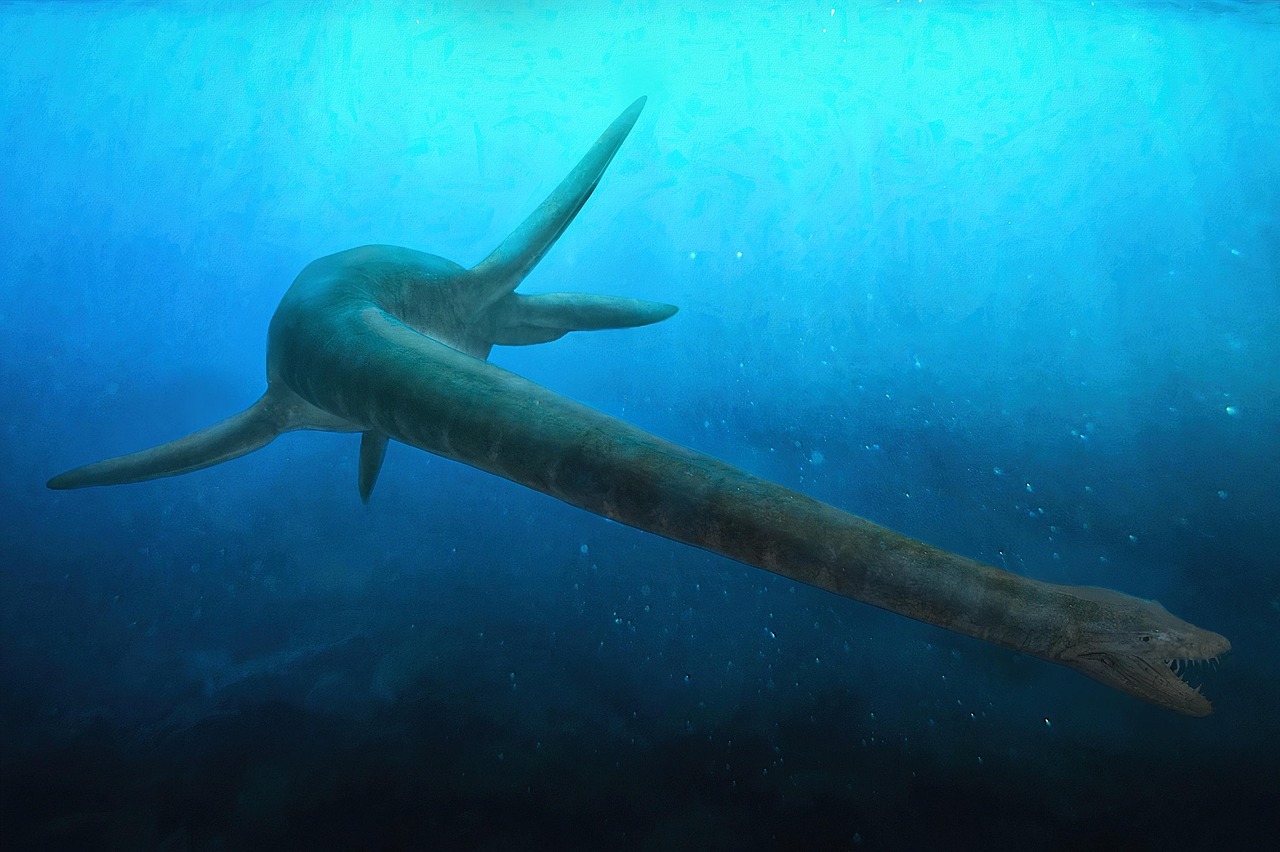

Large marine reptiles would have lived in the ocean alongside ammonites, including ichthyosaurs and long-necked plesiosaurs, creatures that make today’s great white sharks look like minnows. These weren’t just oversized fish – they were apex predators that could challenge even the mightiest land-dwelling dinosaurs in terms of sheer size and hunting prowess. The question isn’t whether they existed, but whether these marine monsters could have held their own against the famous T-Rex and other terrestrial giants.

Size Matters in the Mesozoic Arms Race

In general, plesiosaurians varied in adult length from between 1.5 meters (4.9 ft) to about 15 meters (49 ft). The group thus contained some of the largest marine apex predators in the fossil record, roughly equalling the longest ichthyosaurs, mosasaurids, sharks and toothed whales in size. Think about that for a moment – we’re talking about marine reptiles that stretched as long as modern sperm whales.

But here’s where it gets really interesting: The largest individuals discovered measured up to 15 meters long. That puts some of these ocean dwellers in the same weight class as the largest land dinosaurs. Predatory theropod dinosaurs, which occupied most terrestrial carnivore niches during the Mesozoic, most often fall into the 100–1,000 kg (220–2,200 lb) category when sorted by estimated weight, while these marine giants were operating in an entirely different league.

The Ultimate Marine Predator Arsenal

Thought to have been over 30 feet in length, similar to a double-decker bus. They had long, broad flippers, short, strong necks, huge heads… and enormous jaws. We’re talking about pliosaurs here, and they were absolutely terrifying.

In terms of the deadliest sea monster in prehistoric times, pliosaurs will take the crown on this. While both ichthyosaurs and pliosaurs had similar diets, pliosaurs preyed on other marine predators, including ichthyosaurs! These weren’t just big fish-eaters – they were literally hunting other massive marine reptiles. Picture a creature with Its bite force was more than three times that of the T-Rex with the ability to bite whales in half – and that’s talking about Megalodon, but pliosaurs had comparable crushing power.

Ichthyosaurs: The Ocean’s Speed Demons

If pliosaurs were the tanks of the ancient seas, ichthyosaurs were the fighter jets. Ichthyosaur means “fish lizard” in Greek. They were fish-like in appearance, with a tail and paddle-style appendages used to propel and steer themselves. Though generally about 10 feet in length, certain fossils indicate that some ichthyosaurs could be over 40 feet!

These creatures had evolved something that land dinosaurs never achieved – perfect hydrodynamic efficiency. A deep-diving Jurassic ichthyosaur, Ophthalmosaurus reached 3-4 meters, with eyes proportionally larger than any known marine creature – supported by bony scleral rings to withstand crushing depths. The eyes of Ophthalmosaurus were huge, and these animals likely hunted in dim and deep water. Imagine having eyes so large they could see in the deepest, darkest parts of the ocean where no land animal could ever venture.

The Crocodilian Sea Monsters

While dinosaurs were conquering the land, their crocodilian relatives were staging their own aquatic revolution. The Thalattosuchia, a clade of predominantly marine crocodylomorphs, first appeared during the Early Jurassic and became a prominent part of marine ecosystems. Within Thalattosuchia, the Metriorhynchidae became highly adapted for life in the open ocean, including the transformation of limbs into flippers, the development of a tail fluke, and smooth, scaleless skin.

These aquatic dinosaurs were Nicknamed “Godzilla” for its deep, serrated-toothed skull, Dakosaurus was a 4-5 meter marine crocodile ruling Jurassic-Cretaceous oceans. Its robust jaws and compressed teeth targeted large prey – fish, marine reptiles – anticipating the mosasaurs’ later dominance. They weren’t just surviving in the ocean – they were dominating it with the same ferocity their land-dwelling cousins showed on terra firma.

When Giants Clash: Marine vs Terrestrial Showdowns

Here’s something that’ll blow your mind: there’s actually fossil evidence of marine reptiles tangling with dinosaurs. There is also evidence to suggest that Tylosaurus fed upon dinosaurs, as evidenced by a specimen dubbed the “Talkeetna Mountains Hadrosaur” from the Matanuska Formation in Alaska. We’re talking about a marine reptile literally hunting and eating a land dinosaur.

The Mosasaurus measured up to 59 feet long, bigger than a Tyrannosaurus rex and about the size of a humpback whale today. Think about that comparison – a marine reptile that was actually larger than the most famous land predator in history. Mosasaurus was at the top of the food chain and would eat pretty much anything they found in the ocean: sharks, cephalopods, giant turtles, and even other mosasaurs.

The Physics of Aquatic Gigantism

A lot of these beasts were giants – unlike those that live on land, animals that live underwater aren’t as beholden to the force of gravity and can rely on the buoyancy of water to support a lot of their weight. This means that they’re able to grow to gigantic sizes, sometimes larger than a double-decker bus.

This is the secret weapon that marine creatures had over their land-dwelling counterparts. While dinosaurs had to engineer increasingly complex bone structures and muscular systems to support their massive bodies against gravity, marine reptiles could literally float their way to enormous sizes. It’s like having a built-in weight training system that allows you to bulk up without the usual structural limitations.

Ecosystem Dominance and Niche Control

The higher sea level during the Jurassic and Cenozoic created large areas of shallow seas where toothed fish, reptiles, birds, and flying pterosaurs stalked their prey. These weren’t isolated ocean environments – they were vast, interconnected shallow seas that covered much of what we now consider dry land.

Life was especially diverse in the oceans – thriving reef ecosystems, shallow-water invertebrate communities, and large swimming predators, including reptiles and squidlike animals. The marine environment during the Jurassic wasn’t just diverse – it was absolutely teeming with life at every level of the food chain. At the top of the food chain were the long-necked and paddle-finned plesiosaurs, giant marine crocodiles, sharks, and rays. Fishlike ichthyosaurs, squidlike cephalopods, and coil-shelled ammonites were abundant.

Evolutionary Advantages of Aquatic Life

Plesiosaurs had no gills so they had to come up to the surface for air just like marine mammals do today. A fossil found of a pregnant plesiosaur gives us evidence to support that these creatures gave birth to live young. Unlike modern reptiles, plesiosaurs produced one or a few babies at a time, and they invested a lot in the care of their babies.

This is fascinating because it shows these marine reptiles had evolved sophisticated reproductive strategies that paralleled those of modern marine mammals. Live birth is confirmed by over 50 pregnant specimens, each carrying 2-11 pups, showcasing viviparity as a key adaptation. They weren’t just competing with dinosaurs in size and hunting ability – they were developing advanced parenting strategies that would ensure their offspring’s survival in the dangerous ocean environment.

The Great Marine Reset

The emergence of diverse marine reptiles in the Triassic – the long-necked fish-eating eosauropterygians (pachypleurosaurs and nothosaurs), the mollusk-eating and armored placodonts, the serpentine thalattosaurs, and the streamlined ichthyosaurs – was part of the maelstrom of faunal recovery in the oceans following the devastation of the end-Permian mass extinction. These represented new apex predators, filling trophic levels that had not been widely exploited in the Permian. Most of these marine reptile groups disappeared in the Late Triassic, and were replaced by ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and marine crocodilians as predators in Jurassic seas.

What’s really striking is how the marine environment went through its own evolutionary arms race, completely separate from what was happening on land. While dinosaurs were gradually taking over terrestrial ecosystems, marine reptiles were undergoing their own rapid evolutionary radiation in the oceans.

Competition and Coexistence

Instead, the archosaurs (dinosaurs, crocodiles, and pterosaurs) were the dominant terrestrial vertebrates. It is not clear why this change from synapsid-dominated to archosaur-dominated faunas occurred; it could be related to the Triassic-Jurassic extinctions or to adaptations that allowed the archosaurs to outcompete the mammals and mammalian ancestors.

The interesting thing is that while dinosaurs were establishing their dominance on land, marine reptiles were doing exactly the same thing in the oceans – and they were often larger, more diverse, and arguably more successful in their environment. A possible explanation is an increased competition by sharks, Teleostei, and the first Plesiosauria for some marine niches, showing that even in the ocean, competition was fierce.

The Verdict: Ocean vs Land Supremacy

So could Jurassic marine creatures compete with dinosaurs? The evidence is overwhelming – they didn’t just compete, they often outmatched them. The Jurassic marine reptile found in the museum could have grown to between 9.8 and 14.4 metres long – as big as a bus. Martill and his colleagues used topographic scans to calculate that the Late Jurassic marine reptile found in the museum could have grown to between 9.8 and 14.4 metres long – as big as a bus.

When you consider that these ocean giants had advantages like buoyancy-assisted growth, three-dimensional hunting environments, and sophisticated sensory adaptations for deep-water hunting, they were operating with a completely different set of evolutionary tools than their land-dwelling cousins. The question isn’t whether marine reptiles could compete with dinosaurs – it’s whether dinosaurs could have competed in the ocean realm where these marine monsters ruled supreme.

Conclusion

The Jurassic oceans weren’t just a sideshow to the age of dinosaurs – they were home to some of the most spectacular predators in Earth’s history. These marine giants evolved alongside dinosaurs, often growing larger, developing more sophisticated hunting strategies, and dominating their aquatic realm with the same evolutionary success that dinosaurs showed on land. From the bus-sized pliosaurs with bone-crushing jaws to the deep-diving ichthyosaurs with eyes like dinner plates, these creatures prove that the Mesozoic era belonged as much to the ocean as it did to the land.

The real marvel isn’t that these marine reptiles could compete with dinosaurs – it’s that they created their own parallel empire of giants beneath the waves, one that was every bit as diverse, successful, and awe-inspiring as anything that ever walked the Earth. What would you have expected to find ruling those ancient seas?