Picture this scene from millions of years ago. A shadow sweeps across an ancient grassland, but it’s not from an airplane overhead. It’s from a bird. A bird so massive that its wingspan stretches further than most school buses are long. Somewhere else, thunderous footsteps echo through prehistoric forests as flightless giants, taller than basketball hoops, hunt for prey with beaks designed like battle axes.

This isn’t science fiction. These creatures actually existed, roaming our planet when it looked vastly different from today. From South American grasslands to New Zealand’s ancient forests, these feathered monsters ruled their domains with terrifying efficiency. So let’s dive into the world of prehistoric birds that would make even the bravest among us think twice about stepping outside.

Terror Birds – The Nightmare Predators of South America

Phorusrhacids, colloquially known as terror birds, were among the largest apex predators in South America during the Cenozoic era, rising to prominence roughly 60 million years ago. These weren’t your average backyard birds. Standing up to 10 feet tall, they dominated the continent for millions of years with their massive hooked beaks and powerful legs.

Scientists theorize that the large terror birds were extremely nimble and quick runners, able to reach speeds of up to 48 km/h (30 mph) in short sprints. Once stretched out into its full length in preparation for a downward strike, its developed neck muscles and heavy head could produce enough momentum and power to cause fatal damage to the terror bird’s prey, swinging their head downward with great force, like an axe, to kill their prey.

Kelenken Guillermoi – The Giant with the Massive Skull

Kelenken guillermoi, from the Langhian stage of the Miocene epoch some 15 million years ago, represents the largest bird skull yet found with a 71-centimetre (28 in), nearly intact skull and a beak roughly 46 cm (18 in) long that curves in a hook shape. This terror bird wasn’t just big for the sake of it. Every inch of its anatomy was designed for one purpose: killing.

At 10 feet tall and estimated to weigh around 220-265 pounds, the Kelenken guillermoi was the largest terror bird ever discovered, with the largest bird skull ever discovered, larger than even some horse skulls, and scientists believe that they would have used this skull like an axe on smaller, slower prey. Think of it as nature’s version of a medieval war hammer, but with feathers and an attitude problem.

Argentavis Magnificens – The Flying Titan

Argentavis was among the largest flying birds to ever exist, holding the record for heaviest flying bird, with an estimated mass of 70–72 kg and a wingspan of ≈7 m, about the size of a Cessna 152 light aircraft. Imagine looking up and seeing what appears to be a small plane soaring overhead, only to realize it’s actually a bird with a skull longer than your arm.

With a skull >55 cm long and 15 cm wide, Argentavis was capable of catching sizeable prey with its formidable beak and was a master glider, capable of soaring for great distances at a shallow angle of 3°, continually re-shaping its wings to control its glide. Argentavis is not thought to have been an active predator however due to its body shape, but when hunting actively, Argentavis swooped from high above down onto their prey, grabbed, killed, and swallowed it without landing, with its skull structure suggesting it ate most of its prey whole.

Pelagornis Sandersi – The Ocean’s Wing Master

Pelagornis has the largest wingspan of any bird ever discovered, measuring 7.4m from wingtip to wingtip, more than twice the size of a wandering albatross’, with a staggering wingspan estimated to be between 7 and 7.4 meters (23 to 24.3 feet). This prehistoric seabird didn’t just rule the skies – it owned them completely.

As well as holding the record for the largest wingspan, Pelagornis is also considered the heaviest flying bird of all time and some estimates suggest it was able to fly at speeds of up to 37mph and travel for several days without ever having to land, as it likely inhabited coastal areas and was a masterful flyer despite its enormous size. These birds didn’t have teeth, rather tooth-like projections on the margins of their bills that served a similar function and helped them to grasp slippery fish, using these projections to grip slippery prey.

Haast’s Eagle – The Moa Slayer

Haast’s eagle weighed roughly 18kg and had a wingspan that spanned almost 3m, making it the largest species of eagle currently known to science, with a wingspan reaching nearly 10 feet. This wasn’t just any eagle. This was a bird designed by evolution to take down prey many times its own size.

It even preyed on the moa which was up to fifteen times the weight of the eagle, attacking at speeds up to fifty miles per hour, seizing the prey’s pelvis with the talons of one foot and killing it with a blow delivered to the head or neck with the talons of the other foot, with its striking force equivalent to a cinder block falling from the top of an eight-story building. Together, these adaptations paint a picture of a bird that would have fed by plunging its head deep into the body cavities of its prey to get at nutritious organs, with talons as large as a tiger’s claws and a powerful bill designed for tearing flesh.

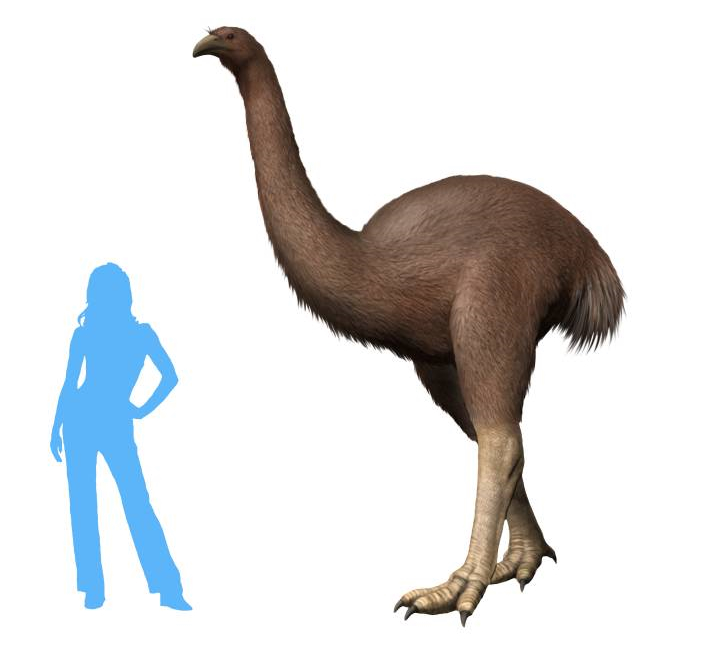

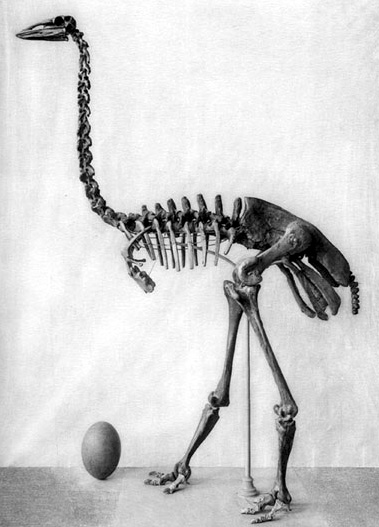

Moa – The Giants of New Zealand

They were the largest terrestrial animals and dominant herbivores in New Zealand’s forest, shrubland, and subalpine ecosystems until the arrival of the Māori, and were hunted only by Haast’s eagle, with moa extinction occurring within 100 years of human settlement. These flightless giants stood as nature’s answer to what happens when birds have no mammalian competitors.

The nine species of moa were the only wingless birds, lacking even the vestigial wings that all other ratites have, with the beak of Pachyornis elephantopus being analogous to a pair of secateurs that could clip fibrous leaves and twigs up to at least 8 mm in diameter, filling the ecological niche occupied in other countries by large browsing mammals such as antelope and llamas. Apart from the Moa’s generally impressive size, these birds had an unusual trait in that they were reverse dimorphic, with the female moas being up to three times as big as the males.

Elephant Birds – Madagascar’s Gentle Giants

The extinct Elephant birds of Madagascar were a group of huge flightless birds, with some reaching up to 3 meters (9.8 feet) tall with long legs and necks with small heads, and thick, conical beaks, which could reach heights of up to 10 feet and weigh as much as 2,000 pounds. Despite their intimidating size, these birds were actually gentle herbivores that wouldn’t hurt a fly.

They laid the largest eggs of any known animals, measuring up to 16 inches long and almost 10 inches wide, which could hold roughly 3 gallons of liquid, equivalent to about 150 chicken eggs, with each egg being 100 or more times the volume of a chicken egg. In 2018, scientists CT-scanned Elephant bird skulls and noticed that their optic lobes were very small, similar to those of the nocturnal kiwi bird, leading scientists to believe that they were truly gentle giants.

Titanis Walleri – The Terror Bird That Crossed Continents

Titanis walleri, one of the larger species, is known from Texas and Florida in North America, making the phorusrhacids the only known large South American predator to migrate north in the Great American Interchange that followed the formation of the Isthmus of Panama land bridge. This terror bird didn’t just stay in South America – it decided to take its show on the road.

These top predators could be either the size of a dog or grow up to nine feet tall, with researchers suggesting this fossil belonged to a previously unknown species that could’ve grown from 5 to 20 percent bigger than other terror birds. The discovery of Titanis proved that terror birds weren’t content to limit their reign of terror to just one continent.

Stirton’s Thunderbird – Australia’s Prehistoric Heavyweight

Gigantic and native to prehistoric Australia, the Stirton’s Thunderbird, Dromornis stirtoni, dwarfs modern Australian fauna, even making modern kangaroos and emus look small, as the gigantic, massive-billed bird was intensely muscular, with a diet that is still up for debate among paleontologists. Australia has always been known for its unique wildlife, but this bird took uniqueness to a whole new level.

Standing taller than modern ostriches and built like a feathered tank, Stirton’s Thunderbird roamed the Australian landscape millions of years ago. Its massive bill and muscular build suggest it could handle just about any food source it encountered, making it one of the most formidable birds in prehistoric Australia’s already impressive lineup of dangerous creatures.

Giant Prehistoric Penguins – The Armored Swimmers

Ponderously sized prehistoric penguins were an intimidating reality in the history of ancient avians, with the archaic penguin species Crossvallia waiparensis being unearthed in New Zealand at a height of five feet, three inches and a weight of 176 pounds, identified as evidence of penguins attaining simply enormous sizes shortly into their evolutionary history. These weren’t the cute, waddling penguins we know today.

Named after the Quechua words for ’emperor’ and ‘water’, Inkayacu is a giant penguin that lived in what is now Peru during the Late Eocene around 35 million years ago, with a nearly complete skeleton found in 2008 on the Pacific coast of Ica, Peru, nicknamed ‘Pedro’. Imagine encountering a penguin that stood as tall as an average adult human, with a spear-like bill designed for catching fish in prehistoric oceans.

Conclusion

These prehistoric birds paint a picture of a world where the sky really was the limit for avian evolution. From the bone-crushing terror birds of South America to the gentle giant elephant birds of Madagascar, each species adapted to fill unique ecological roles that no longer exist today. Most of them disappeared before humans arrived in the Americas, likely driven to extinction by competition with large carnivorous mammals, such as dogs, cats and bears, which migrated south from North America.

Their legacy lives on in the fossil record and in our imagination, reminding us that our planet once hosted creatures that seem almost too incredible to believe. These feathered monsters prove that sometimes reality is far more amazing than any fantasy we could dream up. What do you think about these incredible prehistoric birds? Tell us in the comments.