When you think of the most dangerous dinosaurs, your mind probably drifts toward massive predators with razor-sharp teeth or claws capable of slicing through bone. Yet some of history’s most formidable weapons weren’t found in jaws or talons, but in powerful legs that could deliver devastating kicks. Picture this: a 46-foot-long giant weighing as much as an elephant, capable of launching a lethal strike that could send a predatory raptor flying through the air. This isn’t science fiction – this was the reality of one extraordinary dinosaur that lived over 100 million years ago.

The ancient world was filled with creatures that developed unique ways to survive, and among them stood dinosaurs whose hind limbs became their most fearsome weapons. So let’s explore the fascinating biomechanics behind these prehistoric powerhouses and discover which dinosaur truly earned the title of having in Earth’s history.

Meet Brontomerus: The Thunder Thighs Champion

Brontomerus (from Greek bronte meaning “thunder”, and merós meaning “thigh”) is a genus of camarasauromorph sauropod which lived during the early Cretaceous (Aptian or Albian age, approximately 110 million years ago). It was named in 2011 and the type species is Brontomerus mcintoshi. This remarkable dinosaur literally translates to “thunder thighs” in Greek, and honestly, no name could be more fitting.

It is most remarkable for its unusual hipbones, which would have supported the largest thigh muscles, proportionally, of any known sauropod. This unique ilium would have given it the largest leg muscles of any sauropod dinosaur. The adult specimen is thought to have weighed around six tonnes, and probably measured around 14 meters (46 ft) in length. The juvenile specimen had about a third of this length, and probably weighed around 200 kilograms and measured 4.5 meters (15 ft) in length.

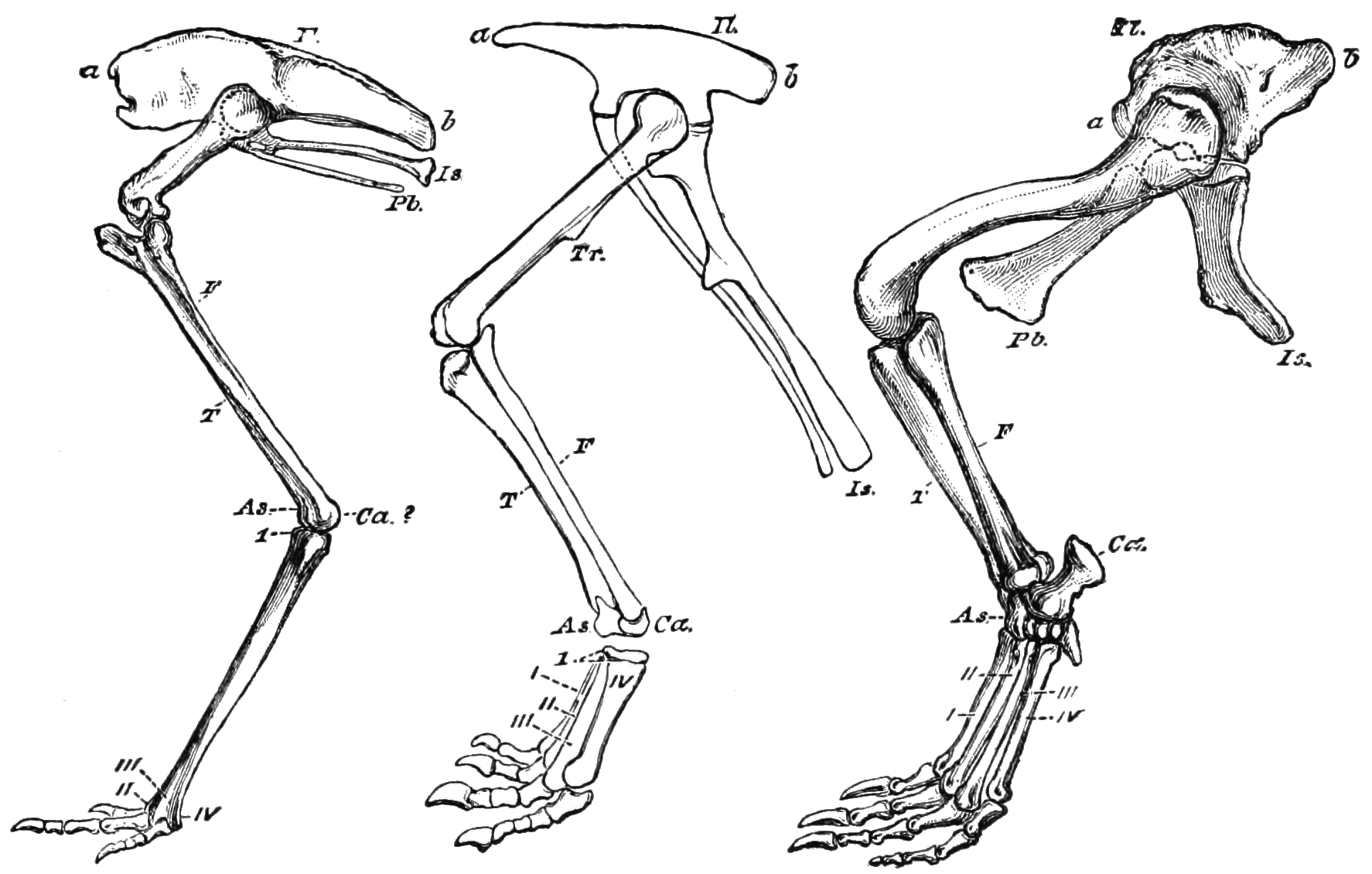

The Anatomy of Devastation

What made Brontomerus such a formidable kicker? The secret lies in its extraordinary hip structure. Its assignment to a new species is based on several noteworthy autapomorphies, including an oddly-shaped hipbone which would have permitted the attachment of unusually massive leg muscles. The ilium is unusual in being very deep and having a front part that is much larger than the part behind the hip socket.

Dr. Michael Taylor, one of the dinosaur’s describers, hypothesizes that the strong thigh muscles of Brontomerus were probably used for functions other than speed. He points out that for fast movement, the strong muscles would be oriented at the back of the leg to pull it along, but the actual positioning of the muscles indicates they were more likely used to deliver a kick. This is due to the apparent anchoring of large femoral protraction muscles, which would have been used to move the leg forward powerfully. Think of it like a massive biological sledgehammer – built not for speed, but for pure devastating impact.

The Science Behind the Power

The biomechanical evidence for Brontomerus’s kicking ability isn’t just speculation. each hind foot, the Utahraptor could deliver a death sentence to a dinosaur with one kick. Based on its size, by rotating its limbs and extending its claw, it could make a cut 5 to 6 feet long with one slice. Wait, that’s about a different dinosaur – let me focus on our thunder-thighed champion.

The 46-foot-long (14-meter-long) Brontomerus mcintoshi had an immense blade on its hipbones where strong muscles would have attached, according to a new study. “These things don’t happen by accident – this is something that’s clearly functional,” said study co-author Mathew Wedel. The team suspects the dinosaur – a type of sauropod, or plant-eating, four-legged lumberer – used its massive legs to either maneuver over hilly ground or deliver “good, hard” kicks to predators, said Wedel, assistant professor of anatomy at Western University of Health Sciences in Pomona, California.

Brontomerus – “thunder thighs” in Greek – may have even attacked like a modern-day chicken, relentlessly kicking and stomping pursuers to death, he added. Imagine encountering a chicken the size of a school bus with legs powerful enough to crush cars!

When Giants Kicked Back

The supposed kicks would have possibly been used for fighting over mates or in defense against predators, such as Utahraptor and Deinonychus. Brontomerus lived about 110 million years ago, during the Early Cretaceous Period, and probably had to contend with fierce “raptors” such as Deinonychus and Utahraptor. Picture this scenario: a pack of deadly raptors approaches what they assume is an easy target – a plant-eating sauropod.

When we recognised the weird shape of the hip, we wondered what its significance might be, but we concluded that kicking was the most likely. The kick would probably have been used when two males fought over a female, but given that the mechanics were all in place it would be bizarre if it wasn’t also used in predator defense. These weren’t just defensive kicks – they were calculated strikes that could potentially be fatal to attackers.

The Raptor Contenders

While Brontomerus holds the crown for sheer kicking power, the raptor family deserves serious consideration for their specialized leg weaponry. It was also suggested that lighter dromaeosaurids such as Velociraptor and Deinonychus relied on their hand claws to handle prey and retain balance while kicking it; in contrast to this, the heavily built Utahraptor may have been able to deliver kicks without the risk of losing balance, freeing the hands and using them to dispatch prey.

Utahraptor’s large sickle-shaped toe claw measured up to 8 inches long, so a kick from this dinosaur could instantly tear a creature open. Additionally, the thickness of the tibia indicates that the animal possessed a significant leg force in order to kill prey. It is the largest known member of the family Dromaeosauridae, measuring about 6–7 metres (20–23 ft) long and typically weighing around 1,500 kilograms (3,300 lb).

Biomechanical Analysis of Raptor Kicks

Modern scientific analysis has revealed fascinating details about raptor kicking abilities. The effectiveness of the enlarged pedal digit II ungual as a disemboweling implement has been challenged by recent experiments using a hydraulic reconstruction of a dromaeosaurid hind limb (Manning et al., 2006). In 2005, Manning and colleagues ran tests on a robotic replica that precisely matched the anatomy of Deinonychus and Velociraptor, and used hydraulic rams to make the robot strike a pig carcass. In these tests, the talons made only shallow punctures and could not cut or slash. The authors suggested that the talons would have been more effective in climbing than in dealing killing blows.

A different study by Peter Bishop modeled the forces produced by raptors’ feet and claws in various positions and leg postures (2019). He found the force produced from the claw tip was actually quite small. Both of these studies concluded the claws were used more for grasping and pinning smaller prey. However, the sheer mass and muscular power behind these kicks shouldn’t be underestimated.

The Raptor Prey Restraint Model

In 2011, Denver Fowler and colleagues suggested a new method by which Deinonychus and other dromaeosaurs may have captured and restrained prey. This model, known as the “raptor prey restraint” (RPR) model of predation, proposes that Deinonychus killed its prey in a manner very similar to extant accipitrid birds of prey: by leaping onto its quarry, pinning it under its body weight, and gripping it tightly with the large, sickle-shaped claws.

Their feathered forelimbs were not used to help grasp prey, but would instead flap to maintain stability while pinning down prey. This feeding style is remarkably similar to birds of prey, where they pin down smaller prey with their claws, flap to maintain control, and feed with their beaks. Yet even if raptors didn’t deliver slashing kicks, their ability to pin and kick simultaneously would have been terrifying for any prey caught in their grasp.

Utahraptor’s Heavyweight Championship

Among all raptors, Utahraptor deserves special recognition for its kicking prowess. Its robust physical build, characterized by strong legs and a sickle claw on each foot, suggests that it used power and precision to subdue animals significantly larger than itself. Like other raptors, the Utahraptor could use those hand claws to grasp prey and kick them, but some evidence suggests that they could balance well enough to kick prey without grasping and then finish them with bites.

Equipped with massive sickle-shaped claws on each hind foot and robust limbs, Utahraptor was built for power and speed. These features enabled it to ambush prey with bursts of speed, eventually overpowering them with strength. Utahraptor’s large size, up to 6 meters long, did not hinder its agility, allowing it to dominate its ecological niche effectively. This combination of size, power, and specialized weaponry made Utahraptor a formidable kicker in its own right.

Speed Versus Power in Dinosaur Kicks

An interesting aspect of dinosaur kicking mechanics involves the trade-off between speed and raw power. Long, powerful hind limbs with specialized muscle attachments indicate strong propulsive capabilities, while their relatively short forelimbs kept their center of gravity optimized for running. However, unlike many modern predators that rely primarily on speed for hunting success, raptors combined moderate speed with exceptional agility, coordination, and lethal weaponry. Their hunting strategy likely emphasized quick acceleration, rapid direction changes, and precision attacks rather than prolonged high-speed pursuits, somewhat similar to how modern birds of prey like hawks and eagles hunt.

Ostrom stated that the “only reasonable conclusion” is that Deinonychus, while far from slow-moving, was not particularly fast compared to other dinosaurs, and certainly not as fast as modern flightless birds. Instead, these dinosaurs prioritized powerful, controlled movements that could deliver maximum impact during crucial moments of predation or defense.

The Four-Wheel Drive Theory

One fascinating theory about Brontomerus suggests its powerful leg muscles served multiple purposes beyond just kicking. Dr. Matthew Wedel, assistant professor of anatomy at the Western University of Health Sciences in Pomona, California, has stated that since it has been commonly been assumed that sauropods tend to prefer drier, upload areas, perhaps Brontomerus may have used its powerful leg muscles for traversing rough, hilly terrain. He described the theoretical use of such muscles in this terrain as “a sort of dinosaur four-wheel drive.”

In addition to powerful protraction muscles, the ilium of Brontomerus would have also anchored abductor muscles, which are muscles used for drawing the leg laterally away from the body. These muscles would have been necessary for creating abduction torque when standing, and could have theoretically aided in an occasional bipedal stance or even limited bipedal walking. This multi-functional approach to leg design shows how evolution can create structures that serve multiple survival purposes simultaneously.

Modern Comparisons and Force Calculations

To put dinosaur kicks in perspective, consider some modern comparisons. Zebras are known for having one of the most potent kicks. Their powerful hind legs can deliver a strike estimated at around 1,000-1,500 pounds per square inch (PSI), a force capable of breaking a crocodile’s jaw or killing a lion. Ostriches, the largest birds on Earth, are renowned for their powerful leg strikes. An ostrich kick can deliver a force of up to 1,500 PSI.

Now imagine scaling these forces up to dinosaur proportions. A creature like Brontomerus, weighing several tons with specialized kicking muscles, would have generated forces that dwarf anything we see in the modern world. Though exact calculations are difficult without complete fossil evidence, the sheer mass and muscle attachment points suggest forces that could easily exceed anything produced by contemporary animals.

The Verdict: Thunder Thighs Takes the Crown

After examining the evidence, Brontomerus mcintoshi emerges as the clear winner for in dinosaur history. Brontomerus literally means “thunder thighs” in Greek, and this particular dinosaur definitely earns the name. It had extremely strong back legs, allowing it to unleash devastating kicks on rivals or predators, as you can see in this absolutely incredible illustration.

The shape of the bone indicates that the animal would likely have had the largest leg muscles of any dinosaur in the sauropod family. This is reflected in the name Brontomerus, which literally means “thunder-thighs.” While raptors like Utahraptor possessed precision striking abilities with their sickle claws, the sheer biomechanical power behind Brontomerus’s kicks would have been unmatched.

“The best we can work out, it could project its leg forward very powerfully – in short, for kicking. We think the most likely reason this evolved was over competition for mates, with males fighting each other or just showing off to win affection of females. [But] it would be bizarre if it wasn’t also used in predator defense.”

The combination of massive size, specialized muscle attachments, and evolutionary pressure created the ultimate kicking machine in Brontomerus. No other dinosaur came close to matching the raw power that these thunder thighs could generate.

What do you think about these prehistoric powerhouses? Could you imagine encountering a creature capable of delivering kicks powerful enough to send modern vehicles flying? The ancient world was truly filled with wonders that continue to amaze us today.