You probably never imagined that some of the world’s most distinguished could be completely duped by fake fossils. Throughout history, fossil hoaxes have not only embarrassed brilliant minds but have also derailed entire fields of research for decades. These elaborate deceptions range from simple pranks gone too far to sophisticated forgeries that fooled entire institutions.

Think you can spot a fake fossil from a mile away? Think again. Some of these fraudulent specimens were so convincing that they shaped scientific understanding for generations, while others were so outrageous that you might wonder how anyone believed them in the first place. Let’s explore the most notorious fossil hoaxes that left red-faced and reshaped our approach to paleontology.

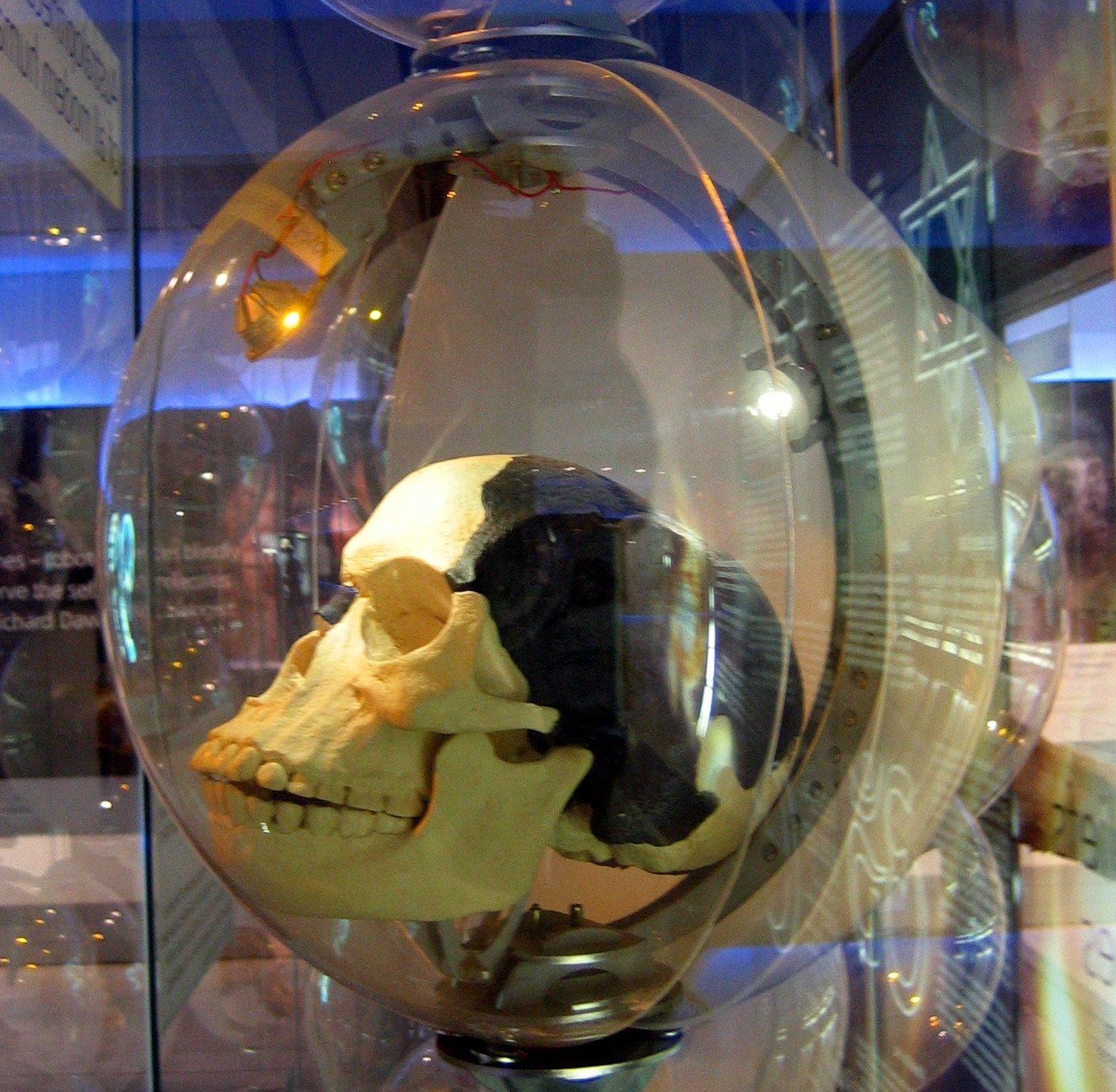

Piltdown Man: The Missing Link That Never Was

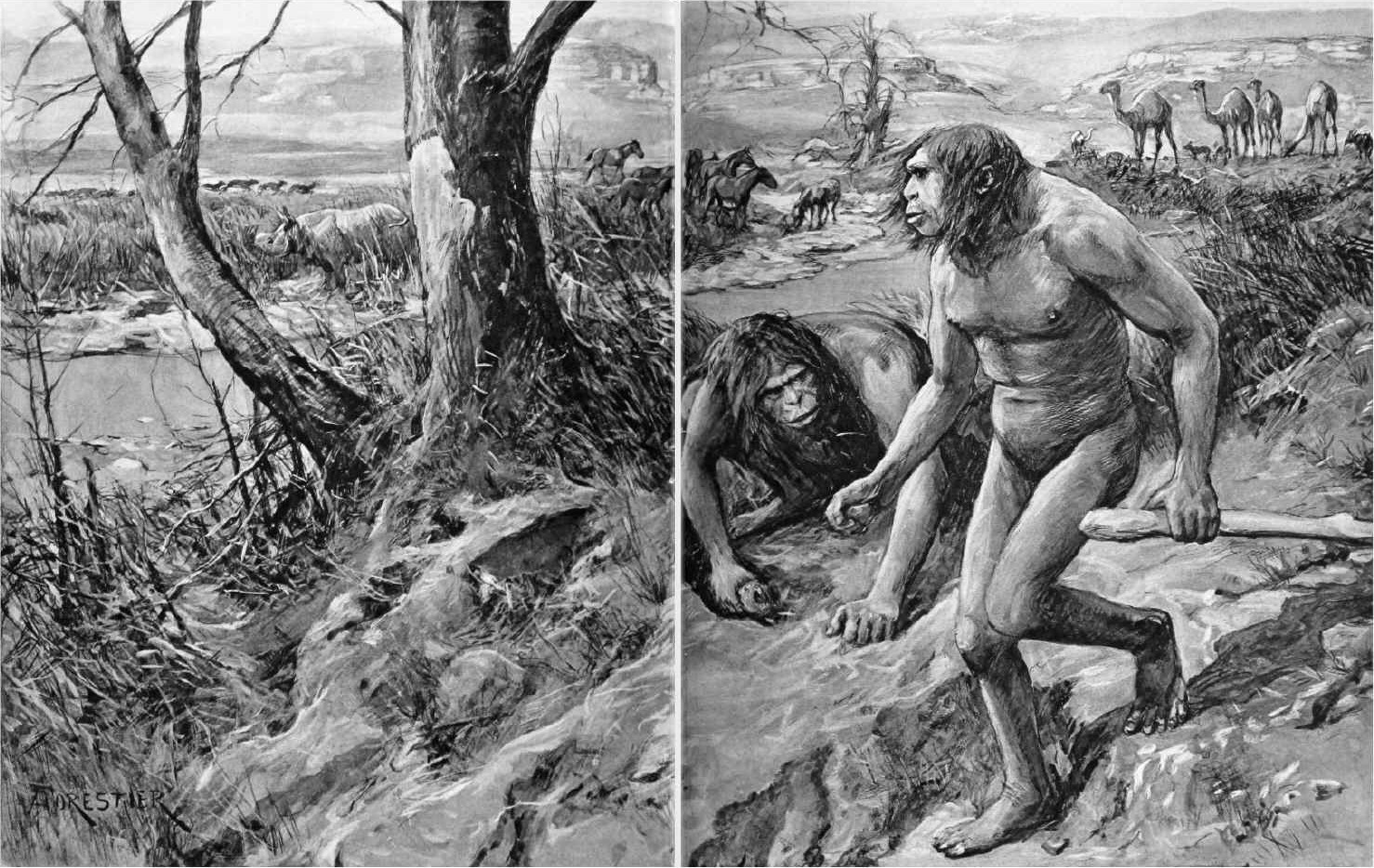

In 1912, British amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson wrote to London’s Natural History Museum claiming to have discovered the missing evolutionary link between apes and humans in a fossil he had dug up in Piltdown, Sussex. This discovery seemed perfectly timed, arriving when the scientific community was desperately searching for evidence to support Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Piltdown Man was an exciting transition: its cranium was shaped like a modern human, while its jaws and teeth were shaped like a modern orangutan … because that’s exactly what they were! The scientific community embraced this “discovery” with open arms, especially British who had felt left out of important fossil finds happening elsewhere in Europe.

Sadly, the damage had already been done: The Piltdown man led many experts to pursue inaccurate ideas about evolution, with close to 250 papers on the forged fossil published before the fraud was found out. exposed the fraud using fluorine dating methods in 1953, determining that the jaw and canine tooth came from an orangutan. In 2016, an eight-year analysis named the hoax’s most likely perpetrator: Dawson himself.

Archaeoraptor: National Geographic’s Greatest Blunder

When a farmer in the late 1990s uncovered a dinosaur fossil in China’s Liaoning providence, they knew they had found a money-maker. The owner of a dinosaur museum in Utah purchased the fossil for $80,000. What happened next would become one of paleontology’s most embarrassing moments.

Dubbed the Archaeoraptor, the fossil was special because it was the first physical evidence of feathers on a dinosaur. National Geographic, however, took interest in the finding and a November 1999 story announced the fossil. The magazine had jumped the gun, bypassing the peer review process that had already rejected the findings.

The scientific community was already pretty skeptical and a CT scan of the bones soon revealed the fossil was a composite, meaning bones were taken from several creatures and glued together. In the end, National Geographic conducted an investigation and confirmed the fossil was indeed a fake. Archaeoraptor was soon dubbed the ‘Piltdown bird’ and the ‘Piltdown chicken’ by the press. For National Geographic – a bastion of publishing usually beyond reproach – this embarrassment would be one of the greatest blunders in its 125-year history.

Beringer’s Lying Stones: Academic Revenge Gone Wrong

In 1726, Beringer published a book illustrating some extraordinary ‘fossils’ reputedly found in the rocks close to Würzburg in southern Germany. However, very soon after its publication, Beringer realised that he had been tricked and that the specimens were fakes.

J. Ignace Roderique, a professor of geography, algebra and analysis at the university, Johann Georg von Eckhart, librarian to the university, and Baron von Hof, a local noble, decided to prank the professor as he was considered arrogant. Roderique had figures carved in limestone and had them planted through one of Beringer’s assistants. Christian Zanger, a 17-year-old the duo hired to polish and distribute the stones, later said they went to all this trouble “because Beringer was so arrogant and despised them all.”

Over six months, his assistants dug up and sold him an estimated 2,000 such carvings. The doctor was duped, and even published a book about the finds one year later, with 21 engraved plates. He took the hoaxers to court and won the case but his reputation was forever besmirched. The stones became known as “Lügensteine” or “lying stones,” earning their place as one of the most extensive fossil hoaxes in history.

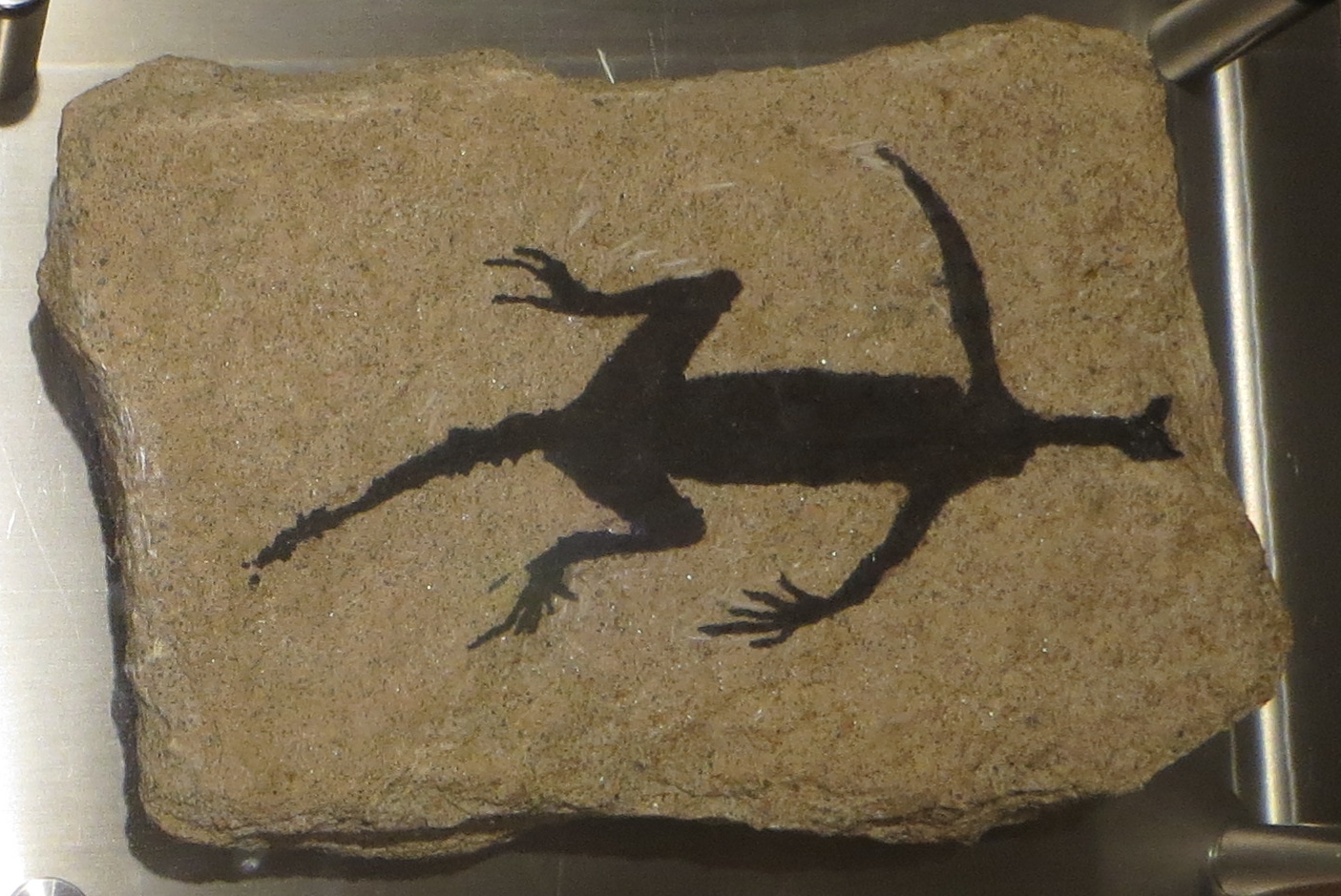

Tridentinosaurus Antiquus: The Painted Reptile

A 280-million-year-old fossil known as Tridentinosaurus antiquus, unearthed in the Italian Alps in 1931, has been revealed to be partially a forgery. For nearly a century, this specimen was celebrated as crucial evidence for understanding early reptile evolution.

New analysis has found, however, that the fossil is actually black paint on a carved piece of stone surrounding a few fossilized bones. “The peculiar preservation of Tridentinosaurus had puzzled experts for decades. Now, it all makes sense. What it was described as carbonized skin, is just paint,” paper co-author Evelyn Kustatscher said.

Researchers analyzed the black material under a microscope and found that its texture and composition did not match that of genuine fossilized soft tissues and was painted on top of the rock. Ultraviolet light photography found that the entire specimen had been coated in some type of varnish. The fossil is not a complete fake, though. The bones of the hindlimbs are genuine, though poorly preserved. This case demonstrates how modern analytical techniques can finally solve decades-old mysteries.

The Cardiff Giant: America’s Greatest Giant Hoax

In 1868, tobacco dealer and science enthusiast George Hull decided that an elaborate hoax would be the best way to discredit a then popular Christian notion that giant humans once roamed the planet. George Hull ordered the gypsum statue to be carved in 1868, moving it slowly between artisans before bringing it to upstate New York. There it was “discovered” in 1869 and became something of an attraction.

Of course, the victims of the hoax weren’t , but the general public dropping a couple quarters to see what they thought was a genuine giant. Still, the Cardiff Giant attracted significant attention from amateur archaeologists and curious who initially debated its authenticity.

Hull himself really just wanted to prove that religious people would buy anything that fit into a Biblical narrative, marking the Cardiff Giant as not just a hoax, but a rather mean-spirited one. The ten-foot tall “petrified man” became a traveling attraction, demonstrating how financial motives could drive elaborate archaeological deceptions.

Nebraska Man: When a Pig’s Tooth Rewrote Human Evolution

There was no deliberate hoax behind Nebraska Man, but there was no Nebraska Man, either. The fossil was that of a wild pig called a peccary. Nebraska Man is another notable hoax that emerged from a single tooth discovery in 1922. The tooth was initially thought to belong to an early human ancestor.

Harold Cook, the rancher who found it, simply believed it to be a higher primate. The press spun it out of control until it was practically a Nebraska caveman. The find caused excitement, leading to significant media coverage and illustrations of the reconstructed figure. Later investigations revealed that the tooth belonged to a pig, rendering the entire claim invalid.

This case shows how innocent mistakes can snowball into major scientific embarrassments when combined with media hype and wishful thinking. This, in turn, caused the creationist community to seize on the fossil as evidence of flimsy evidence for a progression to humanity.

The Piltdown Fly: Baltic Amber Deception

In 1966, when famed German biologist Willi Hennig described what appeared to be a modern-day fly trapped in Baltic amber, it was taken as evidence that the common insect had survived relatively unchanged for 40 million years. The timing of this publication, coincidentally on April Fool’s Day, would later prove ironically appropriate.

It took nearly three decades before another scientist, Andrew Ross, re-examined the specimen and realized that while the Baltic amber was real, someone had actually split it, hollowed it out, inserted a fly they trapped in resin, and resealed the halves. The sophisticated nature of this deception required considerable skill and planning.

Following this discovery, it received the unflattering nickname “Piltdown fly” as a reference to the infamous Piltdown man. This case demonstrates how even apparently straightforward specimens can be expertly manipulated to fool for decades.

Mongolarachne Chaoyangensis: The Giant Spider That Wasn’t

This happened in the case of Mongolarachne chaoyangensis, a supposedly giant spider found in China. It turned out to be a poorly preserved crayfish after painting. The discovery had initially excited arachnologists who thought they had found evidence of prehistoric giant spiders.

Forgers can also use dark brown or black paint to change the appearance of poorly preserved specimens that otherwise would not be of interest to researchers or collectors. This technique of enhancement through paint has become increasingly common in the fossil trade, particularly with specimens from China where commercial fossil hunting is widespread.

The Mongolarachne case highlights how modern commercial fossil markets create incentives for deception, as sellers attempt to transform mundane specimens into valuable rarities. What began as scientific curiosity quickly transformed into commercial fraud when the potential value of the “spider” became apparent.

Chinese Fossil Fraud: The Industrial Scale Problem

The problem of faked fossils in China is serious and growing. It is exacerbated by the fact that most of the fossils are pulled from the ground by desperately poor farmers and then sold on to dealers and museums rather than being found by paleontologists on fossil digs. Many important dinosaur fossils were discovered in the area, and there was a market of collectors eager to pay top dollar. The fossil, however, wasn’t worth enough on its own.

Mark Norell later described as an ‘unfortunate chapter’ in modern paleontology would foreshadow a growing and serious problem of fraudulent fossils being produced on an industrial scale in China. The combination of economic desperation and high collector demand has created a perfect storm for fossil fraud.

Fossil forgeries are partly driven by a thriving collector’s market, says Gabriel-Philip Santos, the director of visitor engagement and education at the Alf Museum of Paleontology in Los Angeles, California. This economic motivation transforms what might once have been academic pranks into serious commercial enterprises. The scale and sophistication of modern Chinese fossil fraud represents a new chapter in paleontological deception.

The Psychological Appeal of Fossil Hoaxes

This is how the Piltdown man hoax worked so well; contemporary expected to see a simple, linear pattern of change and the faked jaw perfectly fitted into these expectations. However, fossil discoveries throughout the second half of the 20th century revealed that the human family tree is far more complex and branching.

often become victims of their own expectations and biases. This is a serious problem – counterfeited specimens can mislead palaeontologists into studying an ancient past that never existed. When a fossil appears to confirm existing theories or fill obvious gaps in the fossil record, researchers may be less inclined to scrutinize it thoroughly.

The stories behind these hoaxes reveal how excitement and deception can intertwine in the search for our ancient past. The desire to make groundbreaking discoveries can cloud scientific judgment, making even experienced researchers vulnerable to sophisticated deceptions. Understanding this human element helps explain how intelligent, careful can fall victim to elaborate frauds.

Conclusion

These fossil hoaxes serve as humbling reminders that science is a human endeavor, complete with all the ambition, rivalry, and occasional gullibility that comes with human nature. From academic revenge schemes to commercial fraud, the motivations behind these deceptions vary wildly, but their impact on scientific progress remains consistently devastating.

We might not be able to put an end to the making of fake fossils, but we are here and ready to unmask them and protect our marvellous fossil heritage. Modern analytical techniques, rigorous peer review, and healthy skepticism now form our best defense against future hoaxes. These stories remind us that extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence, and that the most convincing fake can sometimes be the most dangerous to scientific progress.

What fascinates you more about these cases – the audacity of the hoaxers or the vulnerability of even brilliant ? Share your thoughts in the comments below.