When you think about fossils, you might picture a massive dinosaur skeleton standing in a museum, or perhaps a trilobite preserved in limestone. Though what you’re really looking at are the end results of an incredibly rare and unlikely chain of events that transforms living tissue into stone. Fossilization is a very rare process, and of all the organisms that have lived on Earth, only a tiny percentage of them ever become fossils. To see why, imagine an antelope that dies on the African plain. Most of its body is quickly eaten by scavengers, and the remaining flesh is soon eaten by insects and bacteria, leaving behind only scattered bones. As the years go by, the bones are scattered and fragmented into small pieces, eventually turning into dust and returning their nutrients to the soil. As a result, it would be rare for any of the antelope’s remains to actually be preserved as a fossil.

The story behind each fossil reveals a perfect storm of conditions that had to align just right. Most creatures that die simply return their nutrients to the ecosystem, never leaving a trace of their existence. Yet occasionally, nature creates the ideal circumstances for death to become immortal, preserving organisms for millions of years. Let’s dive into the precise requirements that trigger this extraordinary transformation from bone to stone.

The Death Prerequisites: Hard Parts Give You a Fighting Chance

Your chances of becoming a fossil dramatically improve if you possess hard parts. Fossilization is a physical-chemical process that typically requires three conditions; 1) possession of hard parts, 2) escape from immediate destruction, and 3) the right geochemical conditions in the sediment. Think of hard parts as your fossil insurance policy.

The fossil halls of natural history museums are primarily made up of displays of bones and shells, reflecting the fact that the fossil record is comprised mostly of the mineralized hard parts of organisms. The minerals that make up bones and shells and other hard parts are usually highly resistant to biological decay and physical weathering: they break down at a much slower rate than soft tissues, which often provide food and nutrients to predators, scavengers, and decomposers. Because they are already made of geologically resistant minerals, hard parts have a much higher likelihood of making it to the burial stage of the fossilization process.

Because mammal teeth are much more resistant than other bones, A large portion of the mammal fossil record consists of teeth. Meanwhile, soft-bodied creatures like jellyfish, worms, and slugs have virtually no representation in the fossil record. There is virtually no fossil record of jellyfish, worms, or slugs. Insects, which are by far the most common land animals, are only rarely found as fossils.

Racing Against Decay: The Critical First Hours After Death

Immediately after death an organism experiences necrolysis (death breakup), which is the decay and breakup up of the organism. The primary agents of destruction are biological, mechanical and chemical. You have precious little time before the forces of destruction take over completely.

In all environments, scavengers quickly eat and destroy carcasses. In the process, hard parts are broken up and scattered. In subaquious conditions, boring algae or sponges, worms, bryozoans and bacteria efficiently continue the destruction, unless the organism ends up in anoxic waters or sediments. On land, termites, ants, beetles, worms, fungi, and bacteria also destroy organisms in a short time.

To become fossilized, organisms must be rapidly buried, preferably in a fine sediment with geochemical conditions that favor the exchange of minerals between the sediment and organic components of the organism, and that exchange of minerals is possible because of dissolved minerals in flowing water. If those conditions occur, fossilization must necessarily be a rapid process of a few hours to a few months if it is to occur before decay destroys any record of the organism.

Burial Speed: When Minutes Matter More Than Millennia

The key to fossil formation is thus rapid burial in a medium capable of preventing or retarding complete decay. Think of burial as hitting the pause button on decomposition. The faster you get buried, the better your preservation odds become.

The organism must be quickly covered by sediment after death to protect it from scavengers and decay. The preservation of an intact skeleton with the bones in the relative positions they had in life requires a remarkable circumstances, such as burial in volcanic ash, burial in aeolian sand due to the sudden slumping of a sand dune, burial in a mudslide, burial by a turbidity current, and so forth.

Catastrophic events often create the best fossilization conditions. Mudslides, volcanic eruptions, sudden sandstorm burials, or underwater turbidity currents can instantly entomb organisms. Actually, it is likely that an event of sudden burial killed the animal and started the mineralization processes.

The Geochemical Goldilocks Zone: Getting the Water Chemistry Just Right

Therefore, the third condition for fossilization to occur is the existence of the right geochemical conditions in the sediment for remineralization to occur. The type of chemical conditions depends on the environment in which the organisms were buried. Different conditions and environments may yield different types of preservation, variation in abundance, or a complete lack of fossils.

Water flowing in the sediment surrounding buried organisms allows dissolved minerals to seep through bones, shells, wood or other hard parts and replace them with minerals. The chemistry has to be perfectly balanced. Too acidic and your remains dissolve completely. Too alkaline and mineralization won’t occur properly.

Surrounding water must be saturated with carbonates in order to avoid dissolution of carbonate skeletal remains. Ideal conditions for carbonate preservation are normally found in marine shelf sediments, with a high biomass of organisms that could potentially fossilize. In fresh water, concentrations of calcium carbonate vary considerably, and so preservation in these environments is not as predictable. Carbonate preservation in freshwaters may be referred to as a transient state, because even minor changes in water chemistry, temperature, or pressure may be sufficient to destroy all preservation present at that time.

Location Matters: The Best Places to Die for Eternity

Marine animals living in shallow waters are the most likely to be preserved, especially if fine sediments like mud or sand cover them. Terrestrial organisms are not as likely to be preserved as those from marine habitats. Marine environments consistently offer better preservation conditions than terrestrial ones.

The remains of organisms are typically only fossilized in depositional environments where sedimentation – and therefore burial – is frequent. Examples of common depositional environments are lakes, river deltas, and ocean basins. Organisms that live in these types of environments – or are transported to these types of environments soon after death – are much more likely to be preserved as fossils than organisms that live elsewhere. In general, organisms that live in or near depositional environments have much better fossil records than organisms that live far from such habitats.

The remains of terrestrial faunas and floras are normally encountered in lacustrine, swamp, and fluvial-alluvial deposits because water is almost absolutely necessary for fossilization. Water serves as the essential transport medium for the minerals that eventually replace organic material.

Permineralization: Nature’s Stone-Making Process

Permineralization is a type of fossilization that happens when minerals transported by water fill in all the open spaces of an organism or organic tissue. Permineralization is a type of fossilization that happens when minerals transported by water fill in all the open spaces of an organism or organic tissue. Within these spaces, mineral deposits form internal casts. This process occurs when water carrying minerals from the ground, lakes, or oceans seep into the cells of organic tissue to eventually form a cast of crystals.

The most common method of fossilization is called permineralization, or petrification. After an organism’s soft tissues decay in sediment, the hard parts – particularly the bones – are left behind. Water seeps into the remains, and minerals dissolved in the water seep into the spaces within the remains, where they form crystals. These crystallized minerals cause the remains to harden along with the encasing sedimentary rock.

Permineralized fossils preserve the original cell structure, which can help scientists study an organism at the cellular level. These three-dimensional fossils create permanent molds of internal structures. The mineralization process helps prevent tissue compaction, distorting organs’ actual size. Most dinosaur bones are permineralized.

Replacement: When Minerals Play Body Double

Replacement, the second process involved in petrifaction, occurs when water containing dissolved minerals dissolves the original solid material of an organism, which is then replaced by minerals. This can take place extremely slowly, replicating the microscopic structure of the organism. The slower the rate of the process, the better defined the microscopic structure will be. The minerals commonly involved in replacement are calcite, silica, pyrite, and hematite.

Often both can occur but permineralization can leave original material in the fossil while replacement does not. Often both can occur but permineralization can leave original material in the fossil while replacement does not. Replacement can happen after permineralization, in which case most of the structure gets preserved (but not material) even though replacement occurs.

In some cases, the original shell or bone dissolves away and is replaced by a different mineral. For example, shells that were originally calcite may be replaced by dolomite, quartz, or pyrite. In some cases, the original shell or bone dissolves away and is replaced by a different mineral. For example, shells that were originally calcite may be replaced by dolomite, quartz, or pyrite. Think of a sponge, in permineralization the sponge gets filled in with stuff, in replacement the sponge slowly dissolves but gets replaced by something else dissolved in the water as it leaves charges behind.

Anoxic Conditions: Death by Suffocation Can Mean Life as a Fossil

The best fossilization occurs when there is rapid burial and anoxic conditions to prevent scavenging, no reworking by currents, and diagentic alteration which preserves a fossil rather than destroy it. Oxygen becomes the enemy of preservation when you’re trying to fossilize.

Fossil Lake is thought to have been density stratified like an estuary. Heavier (more dense) salt water occupies the deepest sections of the lake and lighter (less dense) freshwater ‘floats’ above (a remnant of an evaporative phase when the lake was young). This prevents freshwater scavengers from eating dead animals that fell to the bottom of the lake. Lake turnover (where anoxic waters at the bottom mix with oxygen rich water near the surface) did not occur, creating perpetual anoxic conditions along the bottom which discouraged scavengers.

Oxygen in the sediment allows decomposition to occur at a much faster rate, which decreases the quality of the preservation, but does not prevent it entirely. The organisms’ presence shows that oxygen was present, but at worst this “paused” the mineralisation process. Complete absence of oxygen isn’t always necessary, but reduced oxygen levels dramatically improve your fossilization chances.

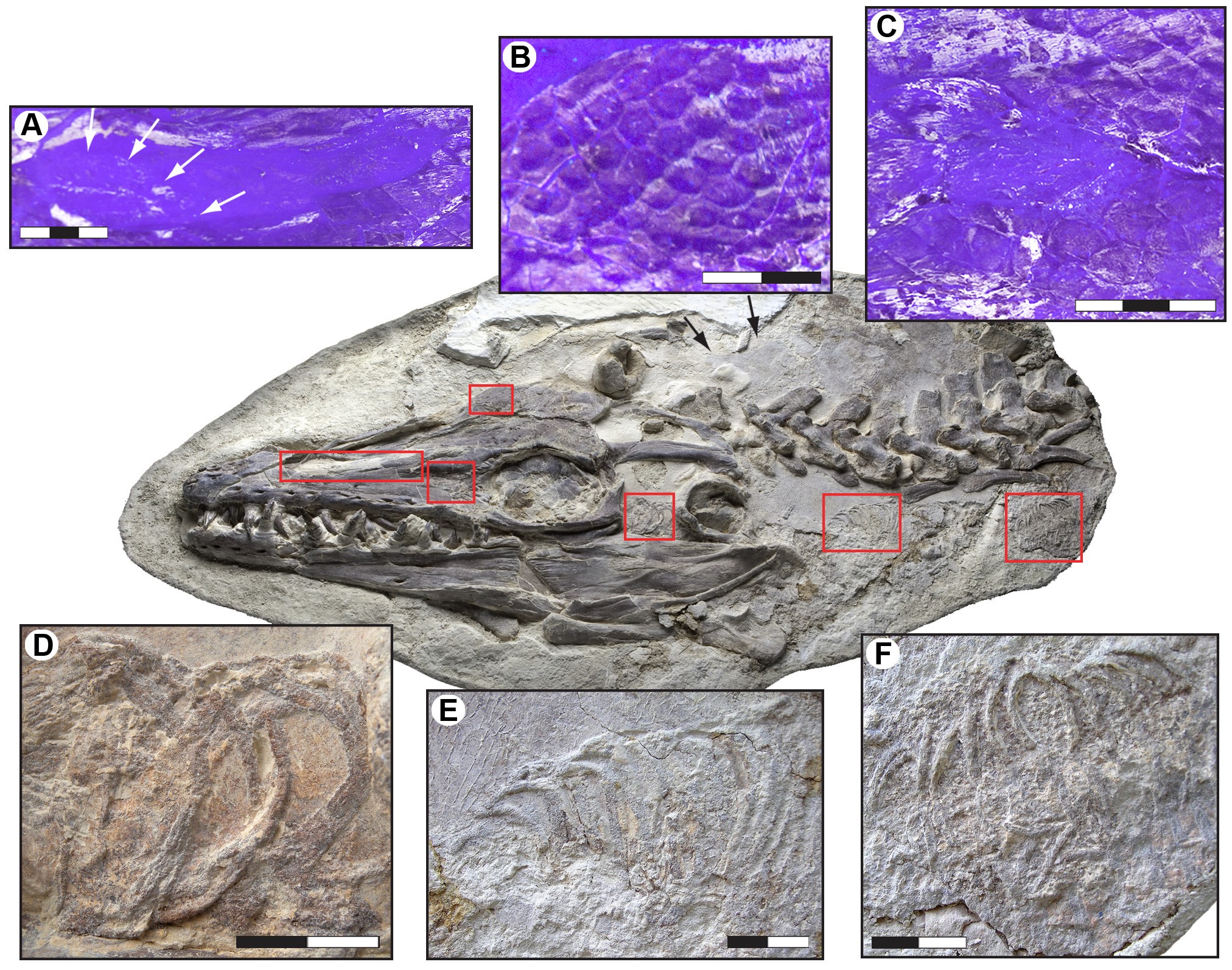

Exceptional Preservation: When Soft Tissues Beat the Odds

The mineralization of soft parts is even less common and is seen only in exceptionally rare chemical and biological conditions. Preservation of remains in amber or other substances is the rarest from of fossilization; this mechanism allows scientists to study the skin, hair, and organs of ancient creatures. Soft tissue preservation requires extraordinary circumstances.

It is famous for the exceptional preservation of the soft parts of its fossils. At 508 million years old (middle Cambrian), it is one of the earliest fossil beds containing soft-part imprints. The Burgess Shale demonstrates what’s possible when conditions align perfectly for soft tissue preservation.

Sulfur isotope evidence from sedimentary pyrites reveals that the exquisite fossilization of organic remains as carbonaceous compressions resulted from early inhibition of microbial activity in the sediments by means of oxidant deprivation. Low sulfate concentrations in the global ocean and low-oxygen bottom water conditions at the sites of deposition resulted in reduced oxidant availability. Thus microbes that usually decompose organic tissues relatively quickly were literally choked. These bed-capping cements resulted from the unusually high alkalinity of Cambrian oceans.

Special Preservation Modes: Nature’s Most Creative Solutions

Amber (soft tissues encased in hardened tree resin). Amber begins as tree resin, oozing from the bark to trap unwelcome invaders or seal wounds. Sometimes, a fly or spider finds itself ensnared. The resin hardens over time, fossilizing into amber – a gemstone of entrapment. What makes amber so remarkable is that it preserves not only the bodies but the moments.

In the Arctic permafrost, where temperatures remain below freezing year-round, mammoths and other Ice Age giants have been found with skin, hair, and internal organs intact. These are not fossils in the traditional sense – they are bodies preserved by cold, arrested in the act of decomposition.

Freezing, drying and encasement, such as in tar or resin, can create whole-body fossils that preserve bodily tissues. These fossils represent the organisms as they were when living, but these types of fossils are very rare. Each preservation mode offers unique insights into ancient life, though all remain exceptionally uncommon.

The Speed of Stone: Fossilization Happens Faster Than You Think

Contrary to what many people believe, permineralization may not take a long time. Given the right geochemical conditions during burial, permineralization can occur relatively rapidly under ideal conditions: typically ranging from months to years, depending on the size and nature of the original material. The transformation from bone to stone doesn’t require millions of years.

Scientists have reported fossilized embryos of echinoderms (sea urchins), which are extremely delicate structures. Experiments carried out to replicate those fossilized embryos show that fossilization happened in a very short span of time. Experiments show that mineralization of soft tissue of shrimp with calcium phosphate mediated by bacterial decomposition may start in a few days and increase in 4 to 8 weeks after death, possibly leading to fossilization. This is an example of fossilization involving mineral precipitation that occurs during the decay process caused by bacteria.

The key factor isn’t time itself, but rather the right chemical conditions occurring at the right moment. Once the proper geochemical environment exists, mineralization can proceed remarkably quickly. The fact that this fossil is preserved in its entirety and in articulation indicates that very little time passed between death, burial, and fossilization. Actually, it is likely that an event of sudden burial killed the animal and started the mineralization processes.

Fossilization emerges as one of nature’s most improbable achievements, requiring a perfect storm of conditions that rarely align. In conclusion, fossilization at least at the present time, is thought to be a very unlikely process and it is believed that only a very small fraction of organisms that lived in the past became fossils. The majority of these fossils were hard skeletal parts or wood. The fossil record represents not a comprehensive catalog of ancient life, but rather a precious collection of extraordinary preservation events.

Every fossil tells a story not just of the organism it preserves, but of the remarkable chain of circumstances that allowed its preservation. From the initial requirement of hard parts to the critical timing of burial, from the precise geochemical conditions to the rare instances of soft tissue preservation, fossilization demands perfection at every step. What fascinates you more about this process: the incredible rarity of the conditions required, or the fact that it can happen so quickly when everything aligns perfectly?