William Buckland stands as one of the most fascinating figures in the early history of paleontology and geology. As both an ordained Anglican priest and a pioneering scientist, Buckland navigated the challenging intellectual waters of early 19th century England where new scientific discoveries increasingly challenged traditional biblical interpretations. His remarkable career reflected a determined effort to harmonize the emerging evidence of ancient extinct creatures with religious belief, particularly as the first dinosaur fossils were being scientifically described. Through eccentric personal habits, groundbreaking scientific work, and theological creativity, Buckland embodied the complex relationship between science and religion during a transformative period in both fields.

Early Life and Education: The Foundations of a Scientific Mind

Born in 1784 in Axminster, Devon, William Buckland grew up in a world still largely understood through the lens of biblical accounts. The son of a clergyman, Buckland showed an early interest in natural history, collecting fossils and geological specimens during his childhood wanderings through the countryside. He received his early education at Winchester College before attending Corpus Christi College, Oxford, where he was awarded a scholarship. Buckland excelled in his studies, eventually becoming a Fellow of Corpus Christi in 1808, further cementing his position within the academic establishment. His dual dedication to religious faith and scientific inquiry was apparent even in these formative years, as he pursued ordination in the Church of England in 1809 while simultaneously developing his geological expertise. These early experiences established the intellectual foundation for his lifelong attempt to reconcile biblical accounts with scientific evidence.

The Oxford Years: Building an Academic Career

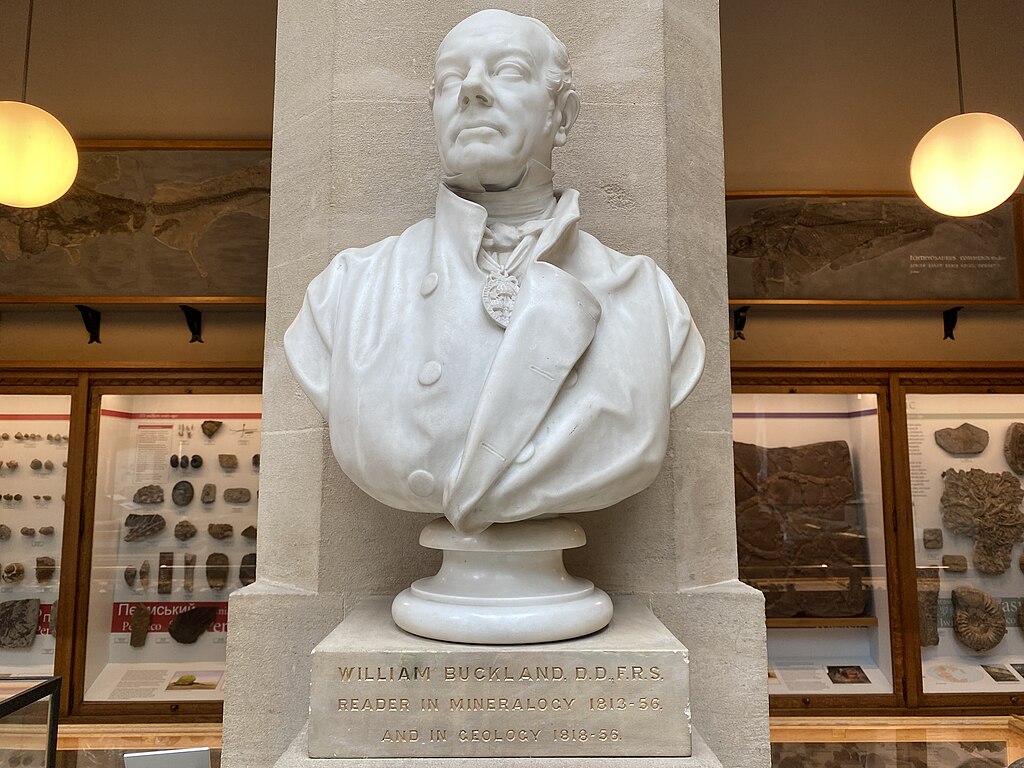

Buckland’s appointment as Oxford’s first Reader in Geology in 1819 marked a significant turning point in both his career and the scientific establishment of the time. This position gave him an influential platform from which to develop and share his geological theories with generations of students. Oxford during this period was still deeply traditional, with theological considerations informing much of academic inquiry. Buckland’s lectures quickly became renowned for their engaging style, practical demonstrations, and his infectious enthusiasm for the subject matter. He would often bring specimens to class, encouraging students to handle and examine fossils directly rather than simply listening to theoretical discussions. During these years, Buckland also assembled an impressive collection of geological and paleontological specimens that formed the foundation of Oxford’s geological museum. His academic reputation grew rapidly, leading to his election to the Royal Society in 1818, an honor that recognized his growing contributions to natural science despite his clerical background.

Discovering the First Dinosaur: The Megalosaurus Breakthrough

Buckland’s most celebrated scientific contribution came in 1824 when he described the first dinosaur ever named in scientific literature. After examining large fossilized bones found in the Stonesfield quarry near Oxford, Buckland realized he was looking at the remains of a massive extinct reptile unlike any known living creature. He named this beast Megalosaurus, meaning “great lizard,” and presented his findings to the Geological Society of London in a landmark paper. This description predated the actual coining of the term “dinosaur” by Richard Owen by nearly two decades, but Buckland’s work was foundational to the emerging understanding of these prehistoric creatures. The Megalosaurus discovery posed significant theological challenges, as it clearly represented an animal that had gone extinct long before human history began. Buckland initially suggested the creature had perished during Noah’s flood, an early attempt to fit this new evidence into biblical chronology. His careful anatomical descriptions of the fossil remains demonstrated his scientific rigor, even as he struggled with the theological implications of creatures that existed in what he came to recognize as “deep time.”

Theoretical Challenges: Catastrophism vs. Uniformitarianism

Buckland emerged as a leading proponent of catastrophism, a geological theory that attributed Earth’s features to violent, sudden events rather than gradual processes. This framework initially seemed compatible with biblical accounts, particularly Noah’s flood, which Buckland initially embraced as the final catastrophe in Earth’s history. His 1823 book “Reliquiae Diluvianae” (Relics of the Flood) argued that geological evidence supported the historical reality of this biblical deluge. However, as more evidence accumulated, Buckland’s thinking evolved considerably. He found himself increasingly at odds with the uniformitarian views championed by Charles Lyell, who argued that slow, gradual processes over immense time periods shaped Earth’s features. The tension between these competing geological theories reflected deeper questions about Earth’s age and the literal interpretation of Genesis. By the 1830s, Buckland had modified his catastrophism to acknowledge multiple floods and catastrophes throughout Earth’s history, effectively extending his timeline beyond biblical chronology. This theoretical shift demonstrated Buckland’s intellectual flexibility and his willingness to adjust his thinking as new evidence emerged, even when it challenged his initial religious interpretations.

The Bridgewater Treatises: Arguing for Divine Design

In 1836, Buckland published his contribution to the prestigious Bridgewater Treatises, a series of books commissioned to demonstrate “the Power, Wisdom, and Goodness of God as manifested in the Creation.” His volume, titled “Geology and Mineralogy Considered with Reference to Natural Theology,” represented his most comprehensive attempt to reconcile his scientific findings with his faith. Throughout this influential work, Buckland argued that geological discoveries revealed God’s design and purpose rather than contradicting scripture. He proposed that the fossil record demonstrated divine planning, with each successive creation showing increasing complexity and perfection. Buckland suggested that apparent extinctions and catastrophes were part of God’s grand plan for Earth’s development, preparing the planet for human habitation. The treatise received mixed reviews, with some religious authorities appreciating his defense of faith while some scientific colleagues found his theological interpretations strained. Despite these criticisms, the Bridgewater Treatise represented Buckland’s most sophisticated attempt to build an intellectual bridge between geology and theology, arguing that properly understood, both revealed complementary aspects of divine truth.

Eccentric Personality: The Omnivorous Professor

Buckland’s personal eccentricities have become almost as famous as his scientific contributions, particularly his determination to taste virtually every animal species he encountered. This unusual habit earned him membership in the “Glutton Club” at Oxford, where adventurous diners sampled exotic meats. Buckland’s palate experienced everything from mice to bluebottles, and he famously claimed to have eaten his way through the entire animal kingdom. Perhaps most notoriously, when presented with the preserved heart of King Louis XIV of France, Buckland immediately consumed it, later remarking that it was among the most distasteful things he had ever eaten. His home reportedly contained an extraordinary menagerie of animals including jackals, eagles, and monkeys, which roamed freely to the consternation of visitors. These eccentric behaviors were not merely colorful quirks but reflected Buckland’s hands-on approach to natural history – he believed in experiencing nature directly rather than merely studying it academically. His unconventional methods and personality made him a legendary figure in scientific circles and contributed to his effectiveness as a public communicator of science.

Exploring Caves: Kirkdale and Beyond

Buckland’s investigation of Yorkshire’s Kirkdale Cave in 1821 represented a turning point in his understanding of Earth’s history and prehistoric life. Upon entering the limestone cave, he discovered an extraordinary collection of fossilized bones from hyenas, elephants, rhinoceroses, and other animals not native to contemporary Britain. Buckland meticulously documented the site, noting that many bones showed evidence of gnawing and concluding that the cave had served as a hyena den before being sealed and preserved. This evidence challenged the prevailing notion that such exotic animals had been swept to Britain by the biblical flood. Instead, Buckland recognized that these creatures had actually lived in Britain during a period when the climate was much warmer. His Kirkdale Cave work earned him the prestigious Copley Medal from the Royal Society and established new standards for cave investigation. Following this success, Buckland systematically explored numerous other caves throughout Britain and Europe, developing the field that would eventually become paleontology. His cave investigations gradually convinced him that Earth had experienced multiple periods of creation and extinction long before human history began, further complicating his attempts to reconcile geology with Genesis.

Buckland and Ice Age Theory: Expanding Earth’s Timeline

Buckland made a significant contribution to the emerging understanding of Earth’s glacial past, though he initially resisted the concept. When Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz proposed that massive ice sheets had once covered much of Europe and North America, Buckland was skeptical, having previously attributed geological features like erratics and striations to Noah’s flood. However, in a remarkable display of scientific open-mindedness, Buckland agreed to accompany Agassiz to the Scottish Highlands in 1840 to examine the evidence firsthand. The expedition proved transformative, as Buckland observed glacial markings that unmistakably matched those found in the Alps. Convinced by direct observation, Buckland promptly changed his position and became one of the most influential early advocates for ice age theory in Britain. This scientific conversion further expanded his conception of Earth’s history and increasingly distanced his geological understanding from straightforward biblical chronology. Buckland’s embrace of ice age theory demonstrated both his intellectual integrity and the ongoing challenge of reconciling emerging scientific evidence with his religious commitments.

Theological Evolution: Adapting Faith to Fossil Evidence

Throughout his career, Buckland’s theological interpretations evolved considerably as he grappled with mounting geological evidence. He initially adhered to the “gap theory,” which proposed that an indeterminate time period existed between the first two verses of Genesis, potentially accommodating millions of years of Earth history before the biblical six days of creation. As more evidence accumulated, Buckland gradually shifted toward the “day-age” interpretation, suggesting that each “day” in Genesis represented an extensive geological epoch rather than a literal 24-hour period. By the 1840s, he had largely abandoned attempts to correlate specific geological events with particular biblical passages, instead advocating a more allegorical reading of Genesis. Buckland increasingly emphasized that God operated through natural laws rather than constant supernatural intervention, a position that anticipated later theistic evolutionary thinking. Despite these theological adjustments, Buckland remained committed to the fundamental compatibility of science and faith, insisting that proper understanding of both would ultimately reveal their harmony. His theological journey reflected the broader intellectual challenges faced by religious scientists as geological timescales expanded dramatically during the early nineteenth century.

The Dean of Westminster: Balancing Church and Science

Buckland’s ecclesiastical career reached its apex in 1845 when Prime Minister Robert Peel appointed him Dean of Westminster, one of the most prestigious positions in the Church of England. This appointment reflected both his religious standing and his scientific achievements, demonstrating that the Victorian establishment could still accommodate figures who straddled both worlds. As Dean, Buckland supervised Westminster Abbey, a responsibility that included caring for the final resting place of many of Britain’s greatest scientists, including Isaac Newton. Buckland used this influential position to continue advocating for scientific education and research within religious contexts, arguing that scientific inquiry constituted a form of devotion to God’s creation. Despite his administrative duties, he maintained his scientific interests, frequently using the Abbey as a platform for public lectures on geology and paleontology. Buckland’s dual role exemplified the complex relationship between science and religion in Victorian Britain, where the institutional separation between these domains remained incomplete. His ability to navigate both worlds with credibility demonstrated that the “conflict thesis” between science and religion oversimplifies the historical reality of figures who genuinely inhabited both realms.

Later Life and Mental Decline

Buckland’s final years were marked by tragedy as his brilliant mind deteriorated due to what modern physicians believe was likely frontotemporal dementia. The symptoms began appearing in the early 1850s, progressively robbing him of his intellectual faculties and distinctive personality. His condition eventually reached the point where he could no longer perform his duties as Dean of Westminster, necessitating his retirement from public life. Buckland’s mental decline was particularly poignant given how much his identity had been defined by his intellectual curiosity and scientific acumen. His family, particularly his son Frank Buckland who followed in his father’s scientific footsteps, cared for him during this difficult period. Queen Victoria, recognizing his contributions to British science, granted a civil list pension to support him and his family. William Buckland died on August 14, 1856, at the age of 73, no longer able to engage with the scientific questions that had animated his life’s work. His intellectual legacy, however, continued through his publications and the many scientists he had influenced during his productive years.

Scientific Legacy: Foundations of Modern Paleontology

Buckland’s scientific contributions extended far beyond his famous dinosaur discovery, establishing fundamental approaches in paleontology that continue to influence the field today. He pioneered the study of coprolites (fossilized feces), recognizing their scientific value for understanding ancient diets and digestive systems. This focus on what many contemporaries considered distasteful material demonstrated Buckland’s dedication to following evidence wherever it led. His approach to fossil analysis emphasized paleoecology – understanding extinct creatures within their ancient environments rather than studying them in isolation. Buckland developed methods for reconstructing prehistoric foodwebs and ecological relationships based on fossil evidence, insights that remain central to paleontological practice. His Oxford lecture series introduced generations of students to geological thinking, with notable pupils including Charles Lyell and Roderick Murchison, who would themselves become influential geologists. Though subsequent researchers would revise many of Buckland’s specific conclusions, his methodological innovations – particularly his insistence on detailed observation, experimental approaches, and ecological context – helped transform natural history into modern scientific paleontology. His work bridged the gap between the earlier tradition of gentleman fossil collectors and the more rigorous scientific approach that would characterize later Victorian science.

The Modern View: Reassessing Buckland’s Reconciliation Project

Contemporary historians of science have increasingly recognized the complexity of Buckland’s position, moving beyond simplistic narratives that portray him as either compromising scientific integrity for religious reasons or abandoning faith for scientific truth. Modern scholarship emphasizes that Buckland genuinely believed in the ultimate compatibility of geological evidence and divine revelation, though his understanding of both evolved throughout his career. His project of reconciliation reflected the intellectual context of early Victorian Britain, where the boundaries between scientific and religious discourse remained fluid and permeable. Buckland’s work anticipated later approaches like theistic evolution that continue to offer frameworks for religious believers engaging with scientific evidence. Recent historical analysis has highlighted how Buckland’s religious commitments sometimes motivated rather than hindered his scientific investigations, as he sought to reveal divine wisdom through natural evidence. His career demonstrates that the relationship between science and religion has historically been more complex and nuanced than popular accounts of inherent conflict suggest. In an era of polarized discourse around science and religion, Buckland’s sincere efforts to bridge these domains offer a historically grounded perspective on their complex relationship.

William Buckland remains a captivating figure precisely because he embodied the intellectual tensions of a transitional era in Western thought. Neither fully modern in his scientific approach nor traditionally biblical in his theology, he navigated a middle path that sought to preserve religious meaning while acknowledging the expanding geological timeline and evolutionary evidence. Though his specific reconciliation strategies may seem outdated to contemporary readers, his fundamental commitment to both intellectual honesty and spiritual meaning continues to resonate. As modern societies continue to wrestle with questions about the relationship between scientific and religious ways of knowing, Buckland’s earnest efforts to integrate these domains remind us that such tensions have deep historical roots. The eccentric clergyman who tried to reconcile God and dinosaurs ultimately succeeded in neither completely harmonizing these worldviews nor completely separating them, but instead demonstrated the rich complexity of living at the intersection of faith and empirical discovery.