The history of paleontology has been marked by many fascinating milestones, but few have captured the public imagination quite like the first life-sized dinosaur models. In the mid-19th century, when dinosaur fossils were still a relatively new discovery, scientists and artists collaborated on an ambitious project that would forever change how humans visualized prehistoric life. The creation of the first complete dinosaur sculptures at Crystal Palace Park in London represented a groundbreaking moment where science and art converged to bring extinct creatures back to life in three dimensions. These revolutionary models not only attracted enormous crowds but also helped establish dinosaurs as cultural icons that continue to fascinate us today.

The Dawn of Dinosaur Discovery

During the early 19th century, paleontology was emerging as a scientific discipline with remarkable fossil discoveries capturing public attention. The term “dinosaur” itself wasn’t coined until 1842 by anatomist Richard Owen, who used it to describe these “fearfully great lizards” that had once roamed the Earth. Before this period, the scattered fossil bones found throughout Europe had been attributed to dragons, giants, or victims of the biblical flood. The scientific community was just beginning to piece together the evidence of an ancient world populated by creatures unlike any living today. These early discoveries, primarily in England, consisted of fragmentary remains that required considerable scientific interpretation to understand how these animals might have appeared in life, setting the stage for the ambitious three-dimensional reconstructions that would follow.

Richard Owen: The Scientific Visionary

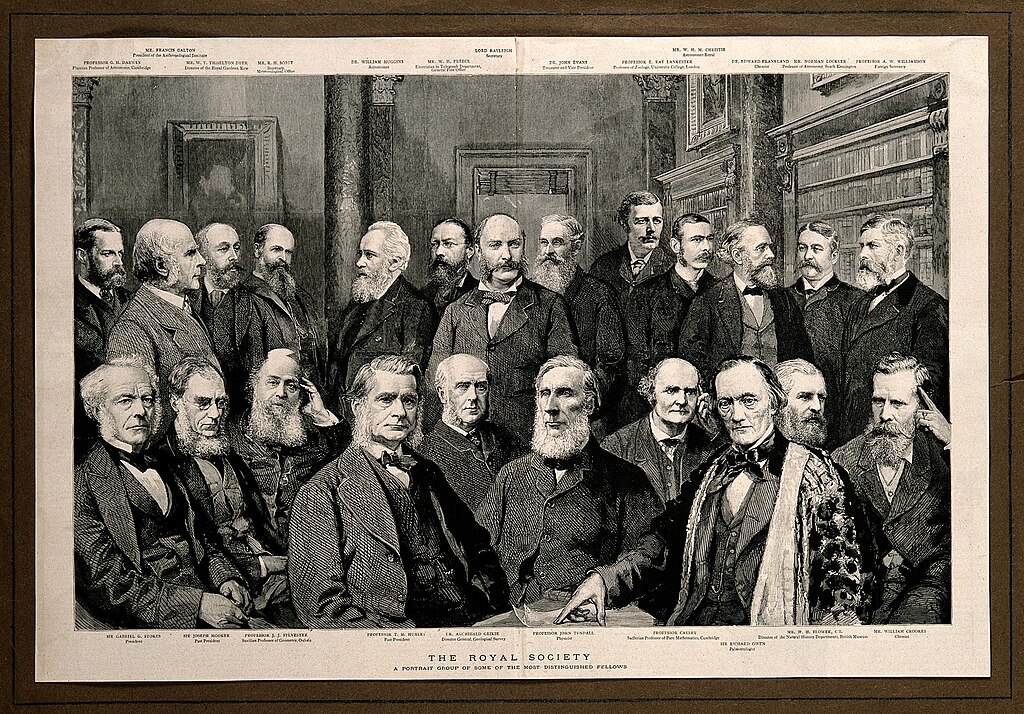

Sir Richard Owen stands as one of the most influential figures in early dinosaur science, though his legacy remains complicated by scientific rivalries and controversies. As Superintendent of the Natural History Department of the British Museum, Owen possessed both the scientific credentials and the institutional power to shape public understanding of dinosaurs. Despite his brilliance, Owen had a reputation for claiming others’ discoveries as his own and fiercely opposing Darwin’s theory of evolution. When the Crystal Palace Park project began seeking scientific expertise for their prehistoric display, Owen seized the opportunity to bring his vision of dinosaurs to life. He provided detailed specifications for the models based on the limited fossil evidence available, conceptualizing dinosaurs as massive, lizard-like creatures—an interpretation that, while inaccurate by modern standards, represented the cutting edge of paleontological knowledge in the 1850s.

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins: The Artistic Pioneer

The task of transforming Owen’s scientific concepts into three-dimensional reality fell to Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, a sculptor and natural history artist with a talent for anatomical precision. Hawkins had previously illustrated zoological works and taught sculpture at the Government School of Design, making him uniquely qualified for this unprecedented project. Working from Owen’s scientific guidance and the fossil evidence available, Hawkins established a studio at Crystal Palace Park where he built enormous models with brick foundations, iron frameworks, and concrete exteriors. His workshop became a destination in itself, with visitors eager to witness the creation process of these prehistoric monsters. Hawkins approached his work with scientific seriousness, studying modern reptiles and elephants to better understand how these extinct animals might have appeared and moved, though his final creations reflected the limited understanding of dinosaur posture and appearance of the time.

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs: A Monumental Undertaking

The dinosaur models created for Crystal Palace Park represented the most ambitious scientific reconstruction project of the Victorian era. Constructed between 1852 and 1854, the display featured not only dinosaurs but a comprehensive collection of prehistoric creatures arranged in chronological order according to geological time periods. The most famous models included the Iguanodon, Megalosaurus, and Hylaeosaurus—the three dinosaur genera known to science at that time. The massive scale of the project was unprecedented; the Iguanodon models stood about 30 feet long, with some requiring interior rooms large enough to host dinner parties during their construction. Each model required tons of clay, iron, and brick, costing around £13,700 in total—equivalent to millions in today’s currency. Despite the enormous expense and technical challenges, Hawkins completed the project in just over two years, creating what would become the world’s first dinosaur theme park.

The Grand Unveiling: A Victorian Sensation

On December 31, 1853, a remarkable event took place that would go down in the annals of both scientific and cultural history—a dinner party held inside the partially completed Iguanodon model. Owen hosted this unusual celebration for twenty-one distinguished scientists and guests, using the occasion to promote his vision of dinosaurs and cement his position as Britain’s leading paleontologist. The formal dinner featured multiple courses, flowing wine, and scientific speeches, all while seated within the concrete ribcage of the model dinosaur. This spectacle generated enormous publicity in newspapers across Britain, building anticipation for the public unveiling of the completed prehistoric park. When Crystal Palace Park officially opened to the public in 1854, with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert in attendance, the dinosaur models instantly became the park’s main attraction, drawing visitors from across Britain and beyond who had never before had the opportunity to visualize these extinct creatures in three dimensions.

Victorian Public Response: Awe, Wonder, and Controversy

The public reaction to the Crystal Palace dinosaurs was overwhelming, triggering what historians now recognize as the first major dinosaur craze in history. Visitors flocked to the park by the thousands, many traveling long distances specifically to see the prehistoric monsters that newspapers had been describing with breathless excitement. Contemporary accounts describe children staring in wide-eyed wonder, adults questioning whether such creatures could truly have existed, and families posing for photographs with the models in the background. The display democratized scientific knowledge, bringing paleontology out of academic circles and into popular culture. Not all reactions were positive, however, as some religious conservatives objected to the implications of extinct species that predated biblical creation accounts. Scientific debates also emerged, with some paleontologists questioning Owen’s anatomical interpretations, foreshadowing the ongoing revisions that would characterize dinosaur science in the decades to come.

Scientific Accuracy: Brilliant Insights and Glaring Errors

Viewed through the lens of modern paleontology, the Crystal Palace dinosaurs represent a fascinating mixture of scientific achievement and misinterpretation. Working with extremely limited fossil material—often just a few teeth and bone fragments—Owen and Hawkins made remarkable deductions about these animals’ general size and form. The Iguanodon was correctly identified as a large herbivore, though it was portrayed as a heavy quadrupedal creature similar to a rhino rather than the partly bipedal animal we now know it to be. The most glaring error involved the placement of the Iguanodon’s thumb spike, which Owen mistakenly believed belonged on the animal’s nose like a rhinoceros horn. The dinosaurs were also portrayed with sprawling limbs like modern reptiles rather than the more upright stance that later evidence would reveal. Despite these inaccuracies, the models represented the best scientific knowledge of their time and established a tradition of updating dinosaur representations as new evidence emerged—a process that continues in museums and media today.

International Influence: Spreading Dinosaur Mania

The impact of the Crystal Palace dinosaurs quickly spread beyond British shores, inspiring similar exhibits in museums and expositions worldwide. International visitors to London returned home with vivid descriptions and illustrations of the models, sparking interest in prehistoric life across Europe and North America. The famous French illustrator Édouard Riou created widely reproduced images of the Crystal Palace display that introduced countless people to dinosaurs who could never visit London personally. American museums began commissioning their own dinosaur models, though none matched the scale of Hawkins’ originals until decades later. When Hawkins himself traveled to America in 1868 to create similar models for Central Park in New York, his partially completed work was unfortunately destroyed in a political dispute, making the Crystal Palace dinosaurs even more significant as the only surviving examples of his groundbreaking prehistoric reconstructions.

Decline and Neglect: The Forgotten Dinosaurs

Despite their initial popularity, the Crystal Palace dinosaurs eventually fell into a period of neglect that threatened their survival. As paleontological knowledge advanced rapidly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the models came to be viewed as scientifically obsolete rather than historically significant. The concrete sculptures suffered damage from weather exposure and vegetation growth, with little funding allocated for their maintenance. During World War II, the park suffered bomb damage that further threatened the prehistoric display. The once-crowded park became less frequented in the post-war period, and by the 1960s, the dinosaur models stood in a state of disrepair, their paint peeling and structures cracking. This period of neglect nearly resulted in the loss of these historic sculptures, as few recognized their cultural and historical importance beyond their outdated scientific value.

Preservation and Heritage Status: Saving the First Dinosaurs

The fortunes of the Crystal Palace dinosaurs began to change in the latter half of the 20th century as historians of science recognized their unique significance in cultural and scientific history. In 1973, the models were listed as Grade II historic structures by the British government, providing them with protected status. A major restoration project followed in the 1990s, repairing structural damage and repainting the sculptures based on historical records of their original appearance. In 2002, the models were upgraded to Grade I listed status—the highest level of protection for historic structures in the UK, placing them in the same category as Buckingham Palace and the Houses of Parliament. This recognition acknowledged not just their artistic and historical value but their significance as artifacts of scientific history that document how scientific understanding evolves over time. Today, the Friends of Crystal Palace Dinosaurs charity works to ensure the ongoing preservation of these remarkable Victorian treasures for future generations.

Modern Visitors: A New Appreciation

Contemporary visitors to Crystal Palace Park experience these historic models with a perspective very different from Victorian audiences. Modern guests arrive with prior knowledge of dinosaurs from films, books, and museum displays, allowing them to appreciate both the historical significance of the models and the ways scientific understanding has evolved since their creation. School groups regularly visit the site as part of lessons on both paleontology and the history of science, learning how scientific knowledge is constructed and revised over time. Photography enthusiasts capture the surreal juxtaposition of Victorian dinosaurs against the modern London skyline, while families continue the tradition of picnicking beside the prehistoric lake. Unlike their Victorian predecessors, who viewed the models as cutting-edge science, today’s visitors appreciate them as beautiful artifacts that tell the story of humanity’s evolving relationship with the prehistoric past—a journey of discovery that continues with each new fossil find.

Legacy and Cultural Impact: Dinosaurs Enter Popular Culture

The Crystal Palace dinosaurs represent the crucial moment when dinosaurs transitioned from obscure scientific specimens to popular cultural icons. The models established visual conventions for depicting prehistoric life that influenced generations of artists, writers, and filmmakers. Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Lost World,” early stop-motion dinosaur films, and even aspects of “Jurassic Park” owe a debt to the imaginative precedent set by Hawkins and Owen. The Crystal Palace display also established the dinosaur park as a form of educational entertainment, a concept that would later evolve into attractions like Disney’s Dinosaur World and countless museum exhibits worldwide. Perhaps most importantly, the models democratized paleontological knowledge, bringing an understanding of Earth’s ancient past to ordinary people regardless of their educational background. This popularization of science helped create an enduring public fascination with dinosaurs that continues to inspire young people to pursue careers in paleontology and related sciences today.

The Enduring Fascination: Why the First Models Still Matter

In an age when digital technology can render photorealistic dinosaurs for films and video games, the crude concrete models at Crystal Palace might seem like mere curiosities. Yet their enduring appeal speaks to something profound about how humans connect with the distant past. The Crystal Palace dinosaurs represent not just outdated science but a pivotal moment in our relationship with prehistoric life—the first time humans could walk beside life-sized representations of extinct animals and imagine a world before human existence. The models capture the Victorian era’s confidence in scientific progress and its fascination with natural history, providing a window into how past generations understood their relationship to Earth’s history. Unlike modern digital dinosaurs that vanish when screens go dark, these physical sculptures have weathered nearly 170 years of British history, becoming part of the landscape both literally and culturally. They stand as monuments not only to extinct creatures but to humanity’s enduring desire to understand and visualize the unimaginably distant past.

The Crystal Palace dinosaurs remain among the most significant artifacts in the history of paleontological science and public education. From their spectacular unveiling to Victorian crowds through periods of scientific revision, neglect, and ultimate recognition as cultural treasures, they trace the evolution of our understanding of prehistoric life. While scientifically outdated, they reveal something more valuable than anatomical accuracy—they document the human journey of discovery itself. As the first attempt to visualize extinct animals in three dimensions for public education, they established dinosaurs as cultural icons and made prehistoric life accessible to ordinary people. Today, as children continue to gaze up at these historical monuments with the same wonder their Victorian predecessors felt, the Crystal Palace dinosaurs remind us that science is not merely a collection of facts but a constantly evolving process of imagination, evidence, and revision—a human story as fascinating as the prehistoric beasts themselves.