Think you know pterosaurs? Those winged reptiles that soared alongside the dinosaurs have been hiding secrets for millions of years. We’re learning that their story was far more complex than anyone imagined. New fossils emerging from sites across the globe are changing everything we thought we understood about these ancient flyers. From their dietary habits to their brain structures, pterosaurs are proving they were remarkably varied creatures that adapted to countless ecological niches.

Let’s be real, the fossil record has been playing tricks on us. We’ve only been seeing the tip of the iceberg when it comes to pterosaur diversity. Recent breakthroughs are revealing that these creatures weren’t just one-trick ponies dominating the skies. They were incredibly specialized, filling roles we never suspected.

A Late Triassic Game Changer From Arizona

Paleontologists excavating a bonebed in Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona recently unearthed the fossilized remains of North America’s oldest known pterosaur, which lived 209 million years ago during the Late Triassic period. This tiny creature was small enough to perch on your shoulder, yet it’s telling us huge things about pterosaur origins.

The new species Eotephradactylus mcintireae means ‘ash-winged dawn goddess’ and references the site’s copious volcanic ash and the animals’ position near the base of the pterosaur evolutionary tree. What’s fascinating is how early these animals were experimenting with flight. This discovery pushes back our understanding of when pterosaurs were diversifying across different continents.

Brain Evolution Was Surprisingly Different From Birds

Here’s where things get wild. A new study published in Current Biology showed that the oldest known pterosaurs lived approximately 220 million years ago and were already animals capable of powered flight. Researchers used high-resolution imaging to reconstruct brain shapes from more than three dozen species, comparing pterosaurs with their relatives and early dinosaurs.

The findings show that enlarged brains seen in modern birds and presumably in their prehistoric ancestors were not the driver of pterosaurs’ ability to achieve flight, and pterosaurs evolved flight early on with a smaller brain similar to true non-flying dinosaurs. They essentially built their own flight computers from scratch, following a completely different evolutionary pathway than birds. That’s pretty remarkable when you think about it.

The Filter Feeders Nobody Expected

Bakiribu waridza is the first filter-feeding pterosaur from the tropics, and it lived in the tropical latitudes of the supercontinent Gondwana during the Early Cretaceous, approximately 113 million years ago. This Brazilian discovery changes our understanding of how pterosaurs fed across different environments.

Bakiribu exhibits extremely elongated jaws and dense, brush-like tooth rows, similar to Pterodaustro but distinct in tooth cross-section and spacing. Even more incredible, the fossils were found inside a regurgitalite, basically ancient vomit from a predator that couldn’t digest the pterosaur bones. Bakiribu adds to growing evidence that the Araripe Basin serves as a critical window into Early Cretaceous biodiversity.

Herbivorous Pterosaurs Shattered Long-Held Assumptions

Nobody saw this coming. Paleontologists found 320 phytoliths, microscopic rigid bodies made of mineral deposits that form inside plant cells, inside the fossilized stomach of Sinopterus atavismus. This marks the first confirmed evidence of plant-eating behavior in pterosaurs.

This discovery marks both the first phytolith extraction from any pterosaur and the second documented pterosaur specimen containing gastroliths. The stomach stones would have helped grind tough plant material. Honestly, it’s hard to say for sure how many other pterosaurs might have been munching on plants, but this single specimen opens up entirely new possibilities about their dietary flexibility.

Scotland’s Middle Jurassic Treasure Trove

A well-preserved fossil uncovered on the Isle of Skye has been revealed as Ceoptera evansae, with an estimated wingspan of 1.6 metres, and would have soared through the Jurassic skies over 165 million years ago. This discovery is filling in crucial gaps during a period when pterosaur fossils are frustratingly rare.

The Middle Jurassic has always been a mystery. Specimens like Dearc and Ceoptera suggest that the Jurassic was much richer in pterosaurs than previously known. These Scottish fossils are proving that pterosaurs were far more diverse during this period than the sparse fossil record suggested. We’re finally getting a clearer picture of how advanced pterosaurs evolved.

Mongolia’s Desert Yields Dual Azhdarchid Species

Palaeontologists have described two new species of azhdarchid pterosaurs from Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, with researchers identifying azhdarchid pterosaur fossils consisting of bones from the neck. These discoveries are particularly significant because pterosaur remains are exceptionally rare in Mongolian deposits.

The coexistence of Gobiazhdarcho and Tsogtopteryx in the same geological formation emphasises that azhdarchids occupied diverse ecological niches, with different body sizes suggesting varied foraging behaviours and diets. One species had a wingspan around three meters, while the other was much smaller. They were sharing the same airspace but hunting completely different prey.

Footprints Reveal Ground-Dwelling Giants

Fossilized footprints reveal a 160-million-year-old invasion as pterosaurs came down from the trees and onto the ground. This research is revolutionary because it links specific track types to the pterosaur groups that made them.

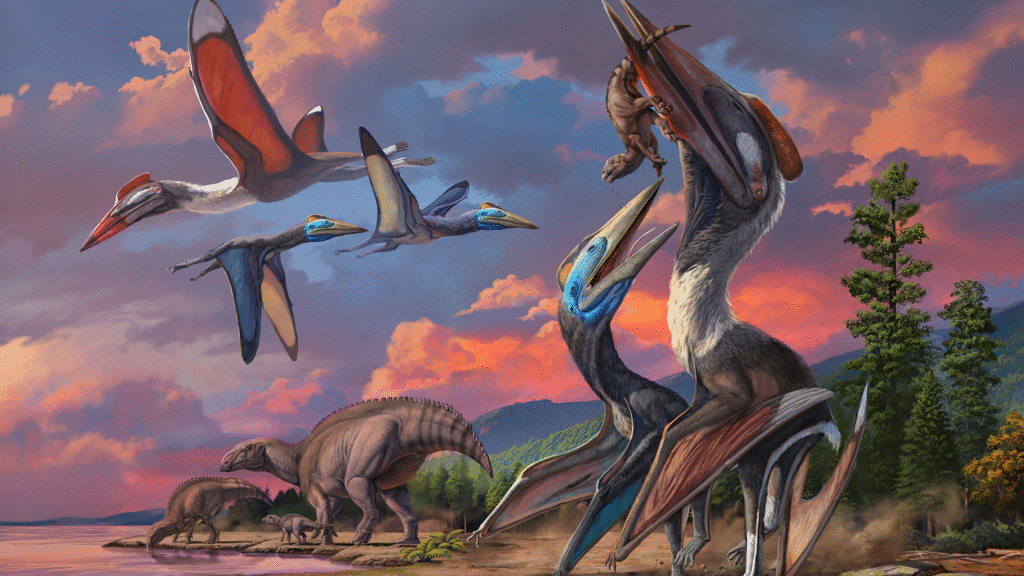

A group of pterosaurs called neoazhdarchians includes Quetzalcoatlus, with a 10 m wingspan, and their footprints have been found in coastal and inland areas around the world, supporting the idea that these long-legged creatures not only dominated the skies but were also frequent ground dwellers. They weren’t just aerial specialists. Some were walking around like modern herons or storks, stalking prey on the ground.

Baby Pterosaurs Died in Ancient Storms

The cause of death for two baby pterosaurs has been revealed in a post-mortem 150 million years in the making, showing how these flying reptiles were struck down by powerful storms that also created the ideal conditions to preserve them. These tiny fossils from Germany’s Solnhofen Limestones tell a tragic but scientifically valuable story.

Nicknamed Lucky and Lucky II, the two individuals belong to Pterodactylus with wingspans of less than 20 cm, and both show the same unusual injury: a clean, slanted fracture to the humerus. The storms that killed these vulnerable hatchlings also created perfect preservation conditions, explaining why most Solnhofen pterosaurs are juveniles while adults are rare.

Morocco’s Phosphate Mines Challenge Extinction Theories

Two Moroccan phosphate mines have yielded dozens of specimens from at least seven different pterosaur species in three different families, suggesting that pterosaurs remained competitive with birds at medium and large body sizes until the mass extinction. This completely contradicts the old idea that pterosaurs were declining before the asteroid impact.

Pterosaurs were actually increasing their functional diversity as the Mesozoic came to a close. Rather than being outcompeted by birds, they were thriving right up until the end. Pterosaurs remained dominant in all ecological niches for wingspans of 2 meters or more. The apparent decline we thought we saw was just a trick of the incomplete fossil record.

These discoveries are rewriting pterosaur history one fossil at a time. Every new specimen reveals adaptations we never predicted, from herbivory to specialized filter feeding to diverse brain evolution. The more we dig, the more we realize how little we actually knew about these magnificent creatures. What other surprises are still buried in the rocks, waiting to challenge everything we think we understand about life in the age of dinosaurs? The next groundbreaking discovery could be just one excavation away.