Have you ever wondered who first set foot on American soil, and when exactly that happened? The story has changed more dramatically than you might think. What archaeologists confidently believed just decades ago has been turned completely on its head. New discoveries keep pushing back the timeline, revealing a far more complex and fascinating tale than the simple narrative we once thought we knew.

The truth is, scientists are still piecing together this ancient puzzle. Every new DNA sample, every ancient artifact pulled from the earth, every bone fragment analyzed adds another layer to our understanding. The journey of how humans first reached the Americas isn’t just about dates and migration routes. It’s about survival, adaptation, and the incredible resilience of people who ventured into completely unknown territory during one of the harshest climate periods in Earth’s history.

The Beringia Gateway: A Lost Continent Beneath the Waves

During the Last Glacial Maximum, when ice sheets covered massive areas of North America between roughly 26,000 and 19,000 years ago, a vast land bridge connected northeastern Siberia to western Alaska. Imagine a landscape nearly as large as Australia stretching across what is now the Bering Strait. This enormous bridge extended from Canada’s Mackenzie River all the way to Russia’s Verkhoyansk Mountains, creating a region scientists now call Beringia.

What’s truly remarkable is just how recently we’ve learned when this bridge actually appeared. Scientists once thought the Bering Land Bridge emerged around 70,000 years ago, but new data shows sea levels only became low enough for the land bridge to appear around 35,700 years ago. This finding is shocking because it shortens the window of time that humans could have first crossed into North America. The land stayed exposed until roughly 11,000 years ago when warming temperatures caused the ice sheets to melt and sea levels to rise again, swallowing Beringia beneath the waves forever.

The Genetic Trail: DNA Tells an Unexpected Story

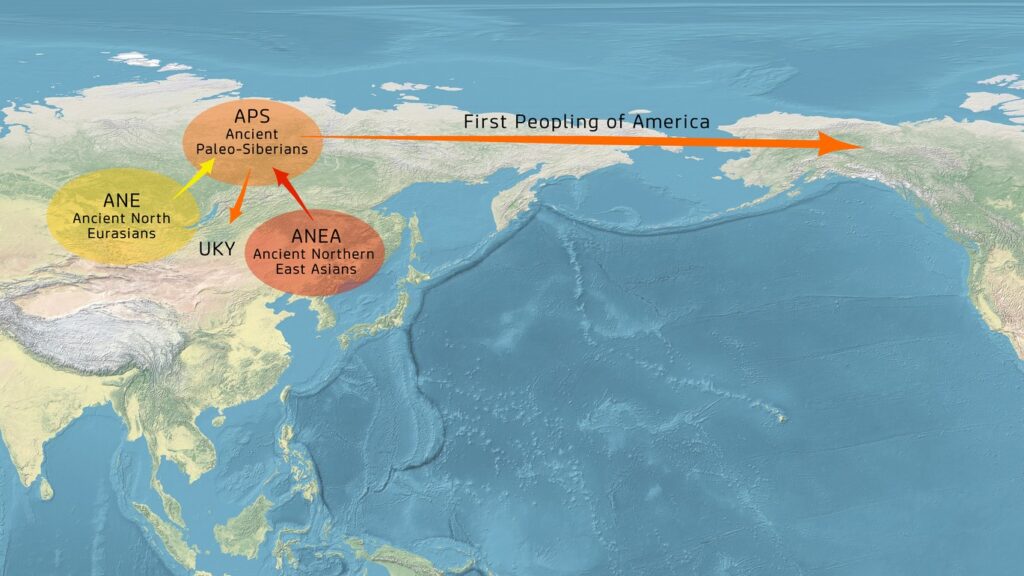

The ancient ancestors of the first Americans left Siberia between 24,000 and 21,000 years ago, confirmed by comparing DNA of Paleo-Americans with DNA of Paleo-Siberians to pinpoint the moment when those two human populations diverged. Think about the scale of what geneticists are doing here. They’re examining mind-bogglingly huge amounts of data, looking for subtle differences in ancient genomes that reveal when populations split apart.

Here’s where it gets really interesting. Genetic studies suggest that the first people to arrive in the Americas descend from an ancestral group of Ancient North Siberians and East Asians that mingled around 20,000 to 23,000 years ago. These weren’t just simple hunter-gatherers wandering aimlessly. Around 20,000 years ago, a group of Asians migrated into Beringia and remained isolated there for thousands of years, during which they evolved the founding lineages seen across the Americas, before migrating out between roughly 17,000 and 16,000 years ago. This period of isolation is known as the Beringian standstill, and it fundamentally shaped who would become the first Americans.

Coastal Voyagers: The Pacific Highway Theory

Most researchers today think the first inhabitants came by sea, whereas archaeologists once thought that the earliest arrivals wandered into the continent through a gap in the ice age glaciers covering Canada. Let’s be real, this completely changes our understanding of these ancient people’s capabilities. Maritime explorers are believed to have voyaged by boat out of Beringia around 16,000 years ago and quickly moved down the Pacific coast, reaching Chile by at least 14,500 years ago.

The evidence keeps mounting. Recent paleogenetic analyses suggest initial colonization from Beringia took place as early as 16,000 years ago via a deglaciated corridor along the North Pacific coast, with ice sheet conditions in southeastern Alaska culminating between 20,000 and 17,000 years ago, and productive marine and terrestrial ecosystems established almost immediately following deglaciation. These early mariners weren’t just surviving. They were thriving in coastal environments rich with fish, shellfish, seabirds, and marine mammals. One ancient fishhook found on Cedros Island, dating to roughly 11,500 years ago, is the oldest fishhook discovered in the Americas.

The Clovis Mystery: Not the First After All

For nearly a century, the Clovis people held the title of America’s first inhabitants. Western archaeologists discovered sharp-edged, leaf-shaped stone spear points near Clovis, New Mexico in the 1920s and 1930s, and the people who made them lived in North America between 13,000 and 12,700 years ago. Clovis points are distinctive projectile points with a fluted, lanceolate shape, sometimes exceeding 10 centimeters in length. These weren’t just weapons. They were multifunctional tools that represented sophisticated craftsmanship.

Yet the Clovis First theory has crumbled. In recent decades, several discoveries have revealed that humans first reached the Americas thousands of years before initially thought and probably didn’t get there by an inland route. Thanks to new archaeological discoveries and more precise dating techniques, we now know that the Clovis people wielding these tools weren’t the first Americans, as researchers have convincingly shown that pre-Clovis people arrived centuries before these tools appear at several sites in North and South America. It’s hard to say for sure, but it seems like the Clovis culture represents just one chapter in a much longer, more complex story.

Pre-Clovis Pioneers: Pushing Back the Timeline

Researchers from Oxford have shown that people were present in North America before, during and after the Last Glacial Maximum, with one site showing evidence that people were present more than 30,000 years ago, raising questions about who these people were and what their fate was. If this holds up under scrutiny, it means humans were exploring the Americas far earlier than anyone imagined possible. At Monte Verde in southern Chile, researchers found remains of an ancient camp dated at 12,500 years old, older than the Clovis cultures, with some remains appearing even older.

The variety of these discoveries is stunning. At Meadowcroft Rockshelter in Pennsylvania, researchers uncovered a stone point more than 12,000 years old unlike anything made by the Clovis people, and in deeper layers found remains of a fire pit and a stone tool dated to 16,000 years ago, making it the oldest tool yet discovered in North America. Fossilized human feces preserved in Oregon’s Paisley Caves, dating to around 14,000 years ago, provide direct evidence for the oldest known human presence in North America and insight into pre-Clovis people’s diet. Honestly, it’s amazing what scientists can learn from ancient poop.

Ancient DNA Revelations: Tracing Bloodlines Across Millennia

The remains of a young boy ceremonially buried some 12,600 years ago in Montana revealed the ancestry of the Clovis culture, and his genome sequence shows that today’s indigenous groups spanning North and South America are all descended from a single population that trekked across the Bering land bridge from Asia. This child, known as Anzick-1, became a crucial link in understanding ancient American ancestry. Anzick-1 is the only human burial directly associated with tools from the Clovis culture, and he has a close genetic relation to some modern Amerindian populations, primarily in Central and South America, and also shares DNA with the 24,000-year-old Mal’ta boy from central Siberia.

The genetic story isn’t simple. The Ancestral Native American lineage underwent several splits, suggesting these people settled in different areas of North America with limited gene flow between them, including one split between 21,000 and 16,000 years ago and a second around 15,700 years ago, when Northern Native Americans separated from Southern Native Americans. Groups that journeyed south of the ice sheets split into two groups, Southern Native Americans and Northern Native Americans, who went on to populate the continents. Every known living Indigenous individual south of Canada belongs to the Southern Native American lineage.

Looking Forward: Questions That Keep Scientists Awake at Night

Despite all these advances, major mysteries remain. There’s no archaeological or genetic evidence of a trans-Pacific migration, though there is a faint signal of shared ancestry between some South Americans and individuals in Australasia that doesn’t match what would be expected from a trans-Pacific migration. Some Amazonian Native Americans descend partly from a founding population that carried ancestry more closely related to indigenous Australians, New Guineans and Andaman Islanders than to any present-day Eurasians or Native Americans. How did this genetic signal get there? Nobody knows yet.

The story gets even more complex when we realize the journey wasn’t one-way. Ancient and modern genomes suggest that although the ancestors of today’s Native Americans came from Asia, the passage was not one way, as the Bering Sea region was a place of intercontinental connection where people routinely boated back and forth for thousands of years. Think about what that means. These weren’t people making a desperate one-time leap into the unknown. They maintained contact, traveled back, and created networks across vast distances we can barely imagine navigating today.

The pieces of this puzzle are slowly coming together, revealing a story far more intricate and impressive than the simple tale of hunters following mammoths across a land bridge. The first Americans were innovators, seafarers, survivors, and explorers who adapted to changing climates and diverse environments with remarkable skill. Their story is written in ancient bones, stone tools buried for millennia, and the DNA of people living today. Every new discovery adds another thread to this incredible tapestry of human achievement and perseverance. What do you think drove these ancient peoples to venture into such unknown territory? Tell us what surprises you most about their journey.