When you look out over American forests, grasslands, or deserts today, you’re essentially viewing a world that’s been profoundly reshaped by absence. The landscape you see is not what it used to be. It’s hard to imagine that roughly ten thousand years ago, North America was home to creatures that would make today’s grizzlies and bison look modest by comparison. Giant ground sloths taller than a pickup truck. Mastodons the size of elephants. Massive beavers weighing as much as a black bear. These weren’t just inhabitants of the land; they were its architects.

When these prehistoric giants disappeared at the end of the last Ice Age, they left behind a landscape that continues to bear the marks of their absence. The ecosystems we walk through today are fundamentally different because these animals are no longer here to shape them. Think about that for a moment. The very structure of American forests, the flow of rivers, even the types of plants that grow in your backyard have all been influenced by creatures that vanished when humans were still learning to farm. Let’s explore how these vanished architects left their fingerprints all over the modern American landscape.

Mammoths and Mastodons Kept Forests in Check

Mastodons were browsers that preferred tree branches and woody vegetation, and they didn’t just eat trees and shrubs – these beasts trampled down paths through woods and scraped their tusks against tree trunks, altering the landscape by stamping out young plants and hindering others’ growth. Picture this: a five-ton animal moving through a forest, knocking over saplings, stripping bark, and creating clearings wherever it went. These proboscideans not only ate vegetation and sprouting trees but actually knocked over trees and trampled the landscape, wreaking havoc on soils and vegetation, keeping it much more open and less forested.

When these herbivores dropped off the landscape, different plant communities emerged – mastodon herds occupied parkland-like landscapes with large open spaces and patches of forest, and when populations crashed, an entirely novel ecosystem emerged as broadleaved trees once kept in check claimed the landscape. Today’s dense northeastern forests? They’re a relatively recent development. Without these massive animals preventing tree growth, woodland spread aggressively. In Alaska and the Pacific Northwest particularly, the loss of mammoths and mastodons affected forests and grasslands and changed small mammal populations. The landscape became less diverse, less dynamic – essentially, less alive.

Ground Sloths Were Nature’s Gardeners and Seed Spreaders

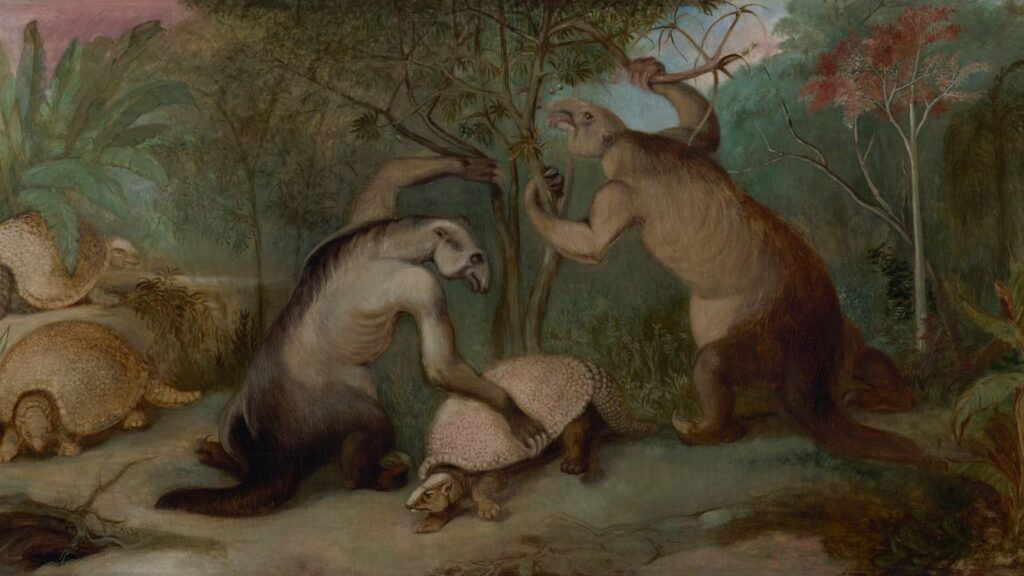

You might think of sloths as lazy tree-dwellers, but their prehistoric ancestors were anything except. Giant ground sloths had the ability to stand on their hind legs like bears and anteaters, and over one hundred species lived throughout North, Central, and South America, ranging from the formidable Megatherium americanum which towered nearly twelve feet tall and weighed up to four tons. These weren’t gentle leaf-munchers hanging from branches. They were powerful, transformative forces.

Evidence shows Paramylodon harlani specialized in hard foods such as roots, tubers, or fungi, and its powerful forelimbs and claws made it a crucial forager of underground resources, bioturbating the soil and dispersing fungi and fruit seeds longer distances than otherwise possible. Think of them as nature’s tillers and planters combined. Giant ground sloths ate the sweet pulp of foot-long woody seed pods, and these multi-ton animals had such big gullets they didn’t chew much, so seeds passed through unharmed and ready to propagate. Plants like avocados and honey locusts evolved specifically to have their seeds dispersed by these giants. When the sloths vanished, these plants lost their primary distribution system. Some tree species today still produce fruits sized for mouths that no longer exist.

Grasslands Expanded Without Their Mega-Grazers

Large browsers like mammoths and mastodons ate small trees and shrubs, uprooting or breaking trees while trampling and churning soil, and other large herbivores like bison and moose kept shrubs in check, playing a key role in keeping forests from overrunning grasslands. The American prairies you imagine when you think of the Wild West? They looked dramatically different when megafauna roamed them. Open grasslands stretched further. The mix of vegetation was richer.

Studies point to the loss of mammoths, native horses and other large animals in Alaska and the Yukon as the reason a productive mix of forest and grassland turned into unproductive tundra that dominates the region today. It’s a sobering thought. What we consider natural wilderness – the Alaskan tundra – is actually a degraded version of what once existed. New species of grazers and ruminants that had high crowned teeth replaced those that couldn’t chew siliceous grasses, including woolly mammoths, rhinoceroses, camels, horses, deer, bison, and pronghorn. Honestly, the entire ecosystem was structured around these animals’ feeding habits.

Wetlands Transformed After Giant Beavers Vanished

About ten thousand years ago, giant beavers weighing as much as one hundred kilograms roamed North America, but research shows they ate submerged aquatic plants rather than wood. Unlike their modern descendants that build elaborate dam systems, the giant beaver was not an ecosystem engineer like the modern beaver – it was not cutting down trees or building giant lodges and dams, and this diet of aquatic plants made it highly dependent on wetland habitat.

When climate shifted and wetlands dried up, giant beavers couldn’t adapt. Modern beavers’ ability to build dams and lodges gave them a competitive advantage because they could alter the landscape to create suitable wetland habitat where required, which giant beavers couldn’t do. By destroying beaver ponds and wetlands through the fur trade, ecosystems became distorted – before sixteen hundred, nearly all the continent except desert sections stretched out as one great Beaverland, a lush wet world whose waterways were diffuse, messy, and incredibly dynamic. The loss of both giant and later many modern beavers fundamentally rewired North American hydrology.

Forest Composition Shifted Without Selective Browsers

Different megafauna species had different dining preferences, and this created a complex mosaic of plant communities. The loss of mammoths and mastodons coincides with a significant increase in deciduous woody tree species – their preferred food source – and analyzing ancient pollen revealed a pronounced increase in alder, ash, birch, and oak. The forests literally changed composition when their primary predators disappeared.

Unlike woolly mammoths, mastodons had shorter legs and were adapted to wooded environments, feeding on twigs, leaves, and branches. Each species maintained different types of vegetation through selective feeding. Mammoth and mastodon populations began dwindling when succeeding vegetation became closed forest with lesser amounts of spruce trees, grasses and sedges, and the last mammoths and mastodons bore signs of stress and competition for the same foods. The ecosystem essentially reorganized itself around the absence of these keystone species. What we consider “natural” forest today is actually just one phase in a continuing transformation.

Soil Structure and Nutrient Cycling Changed Dramatically

Let’s talk about something less glamorous but equally important: dirt. Large browsers like mammoths, mastodons and elephants uproot or break down trees while trampling and churning the soil, and other large herbivores change soil structure and nutrients as they feed, defecate and urinate. These animals were essentially walking fertilizer factories and plows combined. They moved nutrients across vast distances, mixed soil layers, and created disturbances that allowed different plant species to establish themselves.

Paramylodon harlani’s powerful forelimbs and claws made it crucial for bioturbating the soil and dispersing fungi, fruit seeds, and other living organisms longer distances than otherwise possible. When you remove tons of animal biomass constantly churning through vegetation and redistributing nutrients, you fundamentally alter how ecosystems process energy and materials. Mammut americanum altered the world through its habits, and such beasts were ecosystem engineers, as was true of many other herbivores that lived around the world until very recently. The soil beneath your feet has been processing nutrients differently for the past ten millennia.

Fire Regimes Shifted With Vegetation Changes

Here’s something you might not expect: prehistoric megafauna influenced wildfire patterns. Contemporary ecosystems exhibit increases in woody understory and tree-forming plants when megafauna, especially elephants, are removed, and the increase in combustible woody fuel promotes fires. Think about it logically. When large animals keep vegetation trimmed back and create open landscapes, there’s less fuel for fires to spread.

By restoring large herbivores, grazers may reduce fire frequency by eating flammable brush, which would lower greenhouse gas emissions, reduce aerosol levels in the atmosphere, and alter the planet’s albedo. The absence of megafauna created denser vegetation, which meant more intense fires when they did occur. Long-lasting changes appeared in local landscapes after the largest land animals disappeared, and studies point to mammoth and mastodon extinctions in the Pacific Northwest and northeastern United States seeming to have changed vegetation and decreased small mammal diversity. The entire fire ecology of North America adjusted to a new reality without these massive grazers and browsers maintaining vegetation structure.

Water Distribution and Flow Patterns Were Permanently Altered

Along thousands of streams lived beaver colony after colony, as many as three hundred dams per square mile creating wetlands, and as many as two hundred million beavers once lived in the continental United States, their dams making meadows out of forests and wetlands slowly capturing silt. The hydrological landscape of North America was fundamentally different. Water moved more slowly, was stored in more places, and supported vastly more diverse aquatic and wetland ecosystems.

As beavers disappeared, the landscape of North America changed dramatically, and as beavers got trapped out, dams broke down, ponds drained to the ocean, leaving behind rich organic matter and flat, treeless, fertile footprints. Rivers became channels instead of complexes. Wetlands dried up. Beavers can have a dramatic influence on landscape – by building dams they increase watershed resiliency, creating wetlands that store water, slow waterways, mitigate flooding during high flow and release water during low flow. Without the combination of giant beavers and later the massive reduction of modern beavers, North American hydrology was completely restructured. The very way water moves across the continent changed forever.

Conclusion: Living in a Ghost Landscape

You’re walking through what ecologists sometimes call a “ghost landscape” – an ecosystem haunted by the absence of species that once defined it. The forests are too dense, the grasslands too uniform, the rivers too channelized, and the soil chemistry fundamentally altered from what existed for hundreds of thousands of years. The extinction of great Ice Age beasts has created a world dramatically different than the one roamed by shaggy proboscideans and enormous sloths.

Understanding this history isn’t just academic nostalgia. Similar lasting changes could result from the extinction of large land animals today, particularly African elephants. What happened in prehistoric America serves as a warning about what happens when keystone megafauna disappear. The landscape around you tells a story of absence as much as presence – a story written in the spacing of trees, the flow of rivers, and even the types of fruits that fall uneaten to the ground.

Next time you hike through an American forest or drive across prairie lands, try to imagine it teeming with giants. Picture mammoths creating clearings, ground sloths dispersing seeds, and countless beavers engineering waterways. That’s the landscape as it evolved to function. What we have now? It’s just what’s left behind. What do you think – could we ever restore even a fraction of that lost dynamism?