Picture walking through a North American prairie and encountering a woolly mammoth munching on grass beside the highway, or spotting a saber-toothed cat stalking through a suburban park. Sounds like science fiction, right? Yet roughly about a dozen millennia ago, these creatures weren’t fictional characters at all. They roamed freely across the continent alongside dozens of other massive species that have since vanished. The extinction event was massive, mysterious, and has left scientists debating for centuries.

What caused these giants to disappear remains hotly contested, with theories ranging from climate shifts to human hunting. Yet there’s an equally fascinating question that often gets overlooked: what would the world look like if they’d simply…stayed? The ecological ripples from such a scenario would transform everything from the landscapes we know to the very air we breathe. Let’s explore this alternate reality.

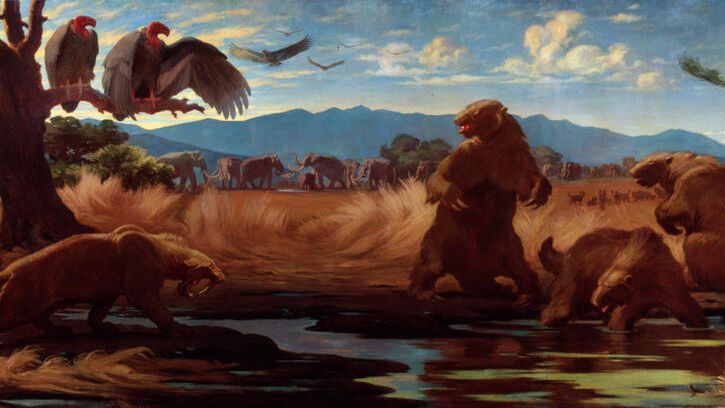

Mammoths as Landscape Architects

Woolly mammoths, standing twelve feet tall at the shoulders and weighing six to eight tons, used their colossal fifteen-foot curved tusks to dig under the snow for food and defend themselves against predators. These weren’t just oversized elephants wandering aimlessly. They were ecosystem engineers of the highest order, physically reshaping their environment with every meal and migration.

If mammoths had survived, vast stretches of North America would maintain the open grassland steppes they preferred. Think about it: modern elephants in Africa push over trees, create water holes, and maintain savannah landscapes through their daily activities. Mammoths would’ve done the same across temperate regions. Forests that currently dominate many northern areas might instead be patchy mosaics of woodland and prairie, offering dramatically different habitat structures. The Ice Age landscape wasn’t meant to disappear entirely.

The Saber-Toothed Predator Web

Smilodon hunted large herbivores such as bison and camels in North America, and it remained successful even when encountering new prey taxa in South America. These iconic predators with their massive canine teeth weren’t solitary movie monsters. They likely hunted in coordinated groups, taking down prey far larger than themselves.

With saber-toothed cats still prowling the continent, you’d see a completely different balance in predator-prey dynamics. Modern apex predators like wolves and mountain lions would face stiff competition from these specialized hunters. Prey species such as elk, deer, and surviving bison would develop different anti-predator behaviors. Herding patterns might be tighter, migration routes more calculated. The tension between predator and prey would create landscapes shaped by fear ecology, where herbivores avoid certain areas entirely, allowing vegetation to flourish in predator-heavy zones. It’s a bit unsettling to imagine, honestly.

Ground Sloths and Forest Dynamics

The giant ground sloths of the late Pleistocene were bear-sized herbivores that stood twelve feet on their hind legs and weighed up to three thousand pounds. These weren’t your typical tree-hanging sloths. Ground sloths were massive terrestrial browsers that shaped plant communities through their feeding habits.

Surviving ground sloths would maintain entirely different forest structures throughout the Americas. Their browsing would prevent certain tree species from dominating, while their seed dispersal would spread others far and wide. Some plants alive today still bear thorns and chemical defenses that evolved specifically against megafaunal browsers. Without ground sloths, these defenses became pointless evolutionary baggage. If the sloths had persisted, these plants would retain their competitive advantages, fundamentally altering which species dominate various ecosystems. Certain fruits with thick rinds or large seeds might be far more common, as they evolved to be dispersed by these giants.

Grassland Ecosystems Under Mega-Herbivore Pressure

Enhanced plant productivity and megafauna that could graze around the clock could grow larger during the summer, and with nutritious plant growth, the megafauna also would have been able to consume enough in the summer to put on reserves. The relationship between massive grazers and grasslands was symbiotic in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

Multiple species of mega-herbivores grazing simultaneously would create incredible habitat diversity. You’d find closely cropped areas beside tall grass meadows, trampled wallows next to undisturbed patches. This patchwork creates microhabitats for countless smaller species. Modern bison create similar effects on a smaller scale, but imagine that multiplied across mammoths, ancient horses, camels, and various other large grazers. Bird diversity would likely skyrocket in these heterogeneous landscapes. Small mammal communities would be richer. Grasslands would be resilient, productive ecosystems rather than the simplified agricultural monocultures we see today.

Nutrient Cycling on a Continental Scale

Megafauna play a significant role in the lateral transport of mineral nutrients in an ecosystem, tending to translocate them from areas of high to those of lower abundance through their movement between consumption and elimination. In South America’s Amazon Basin, such lateral diffusion was reduced over ninety-eight percent following the megafaunal extinctions that occurred roughly twelve thousand five hundred years ago.

With megafauna still roaming, nutrients would flow across the landscape in ways impossible in their absence. These animals eat in one location and defecate in another, often miles away. This transports phosphorus, nitrogen, and other essential elements from nutrient-rich areas to nutrient-poor zones. Rivers would carry different chemical signatures. Soil fertility patterns would be more evenly distributed. Agricultural productivity might actually be higher in certain regions due to this natural fertilization system. The Amazon, as one example, would function quite differently with giant ground sloths and other mega-herbivores still redistributing nutrients from the Andes across the basin.

Methane Emissions and Climate Impacts

After early humans migrated to the Americas about thirteen thousand years ago, their hunting led to megafaunal extinction, decreasing methane production by about nine point six million tons per year, and the absence of megafaunal methane emissions may have contributed to abrupt climatic cooling. Large herbivores are walking methane factories due to their digestive processes.

If megafauna persisted, atmospheric methane levels would be measurably higher. This sounds concerning in our current climate crisis context, yet the relationship is complex. Higher methane might have prevented certain cooling events in the past, maintaining different temperature regimes. Some models suggest this could have delayed the onset of the next glacial period. The climate you experience would genuinely be different, potentially warmer by a degree or two globally. It’s wild to think that extinct animals might still be influencing our weather patterns through their absence.

Fire Regimes and Vegetation Structure

Megafauna removal can trigger changes in vegetation structure and species composition, reductions in environmental heterogeneity, and increases in fire frequency and intensity, with ecosystems most prone to shift being those simultaneously impacted by both climate change and defaunation. Large herbivores are nature’s lawn mowers and their absence fundamentally changes fire behavior.

With megafauna grazing constantly, fuel loads for fires would be dramatically reduced across vast areas. Less accumulated plant matter means fewer intense wildfires. You’d see more frequent but smaller fires that maintain grasslands without destroying forests. Many plant species that currently dominate fire-prone regions might be rare or absent. The West Coast fire seasons that devastate communities in our timeline might be far less severe. Indigenous peoples recognized this relationship and managed landscapes partially through controlled burns, but megafaunal grazing would have provided an additional, constant pressure against catastrophic fire buildup.

Human Civilization in a Megafauna-Rich World

Here’s where things get really intriguing. In North America, thirty-two genera of large mammals vanished during an interval of about two thousand years, centered on eleven thousand years ago. If they hadn’t, human development would’ve taken radically different paths.

Agriculture might have emerged differently, or perhaps not at all in certain regions where megafauna remained dominant. Domestication of these giants could have occurred, similar to how elephants were tamed in Asia. Imagine mammoths pulling plows or transporting goods. Cities would be designed with megafauna corridors and barriers. Certain technologies might have developed faster, others slower. Conservation efforts would be normalized from the start, rather than being a modern concept. The cultural mythology and art of civilizations would be saturated with these creatures in living memory rather than as distant fossils. Transportation networks would route around seasonal migration paths. Honestly, every aspect of how human societies organized themselves spatially and economically would be transformed by the continued presence of these massive animals.

The Ecological Complexity We Lost

The comparative lack of megafauna in modern ecosystems has reduced high-order interactions among surviving species, reducing ecological complexity, and this depauperate, post-megafaunal ecological state has been associated with diminished ecological resilience to stressors. We live in a fundamentally simplified world.

Ecosystems with their full complement of megafauna would exhibit resilience we can barely imagine. The complex web of interactions between apex predators, mega-herbivores, smaller predators, prey species, plant communities, and microorganisms would create systems that could absorb shocks and disturbances without collapsing. Modern conservation biology is attempting to restore some of these interactions through rewilding projects, reintroducing species like bison and wolves. These efforts show promising results, yet they’re recovering a fraction of what was lost. A world where the extinctions never happened would have maintained this complexity uninterrupted for the past ten millennia, with ecosystems fine-tuned by eons of coevolution rather than scrambling to adapt to sudden absences.

The absence of these giants leaves us with diminished ecosystems functioning below their potential. Their return through de-extinction technologies or careful rewilding might help us glimpse what we’ve been missing. What would you think about sharing your world with mammoths?