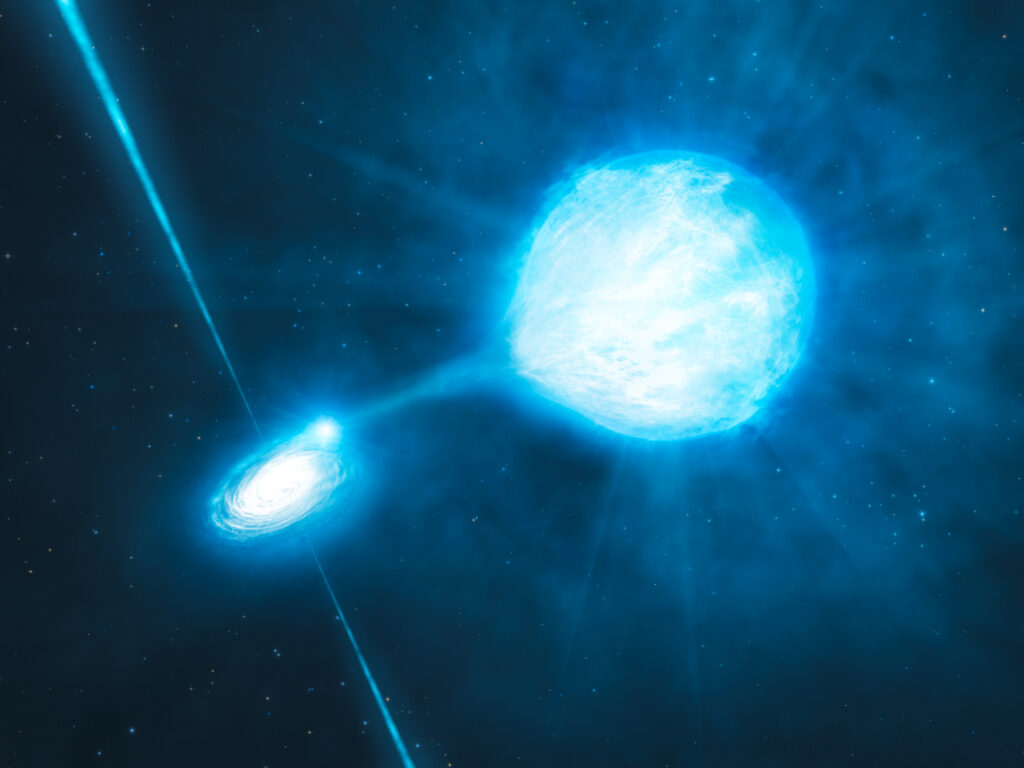

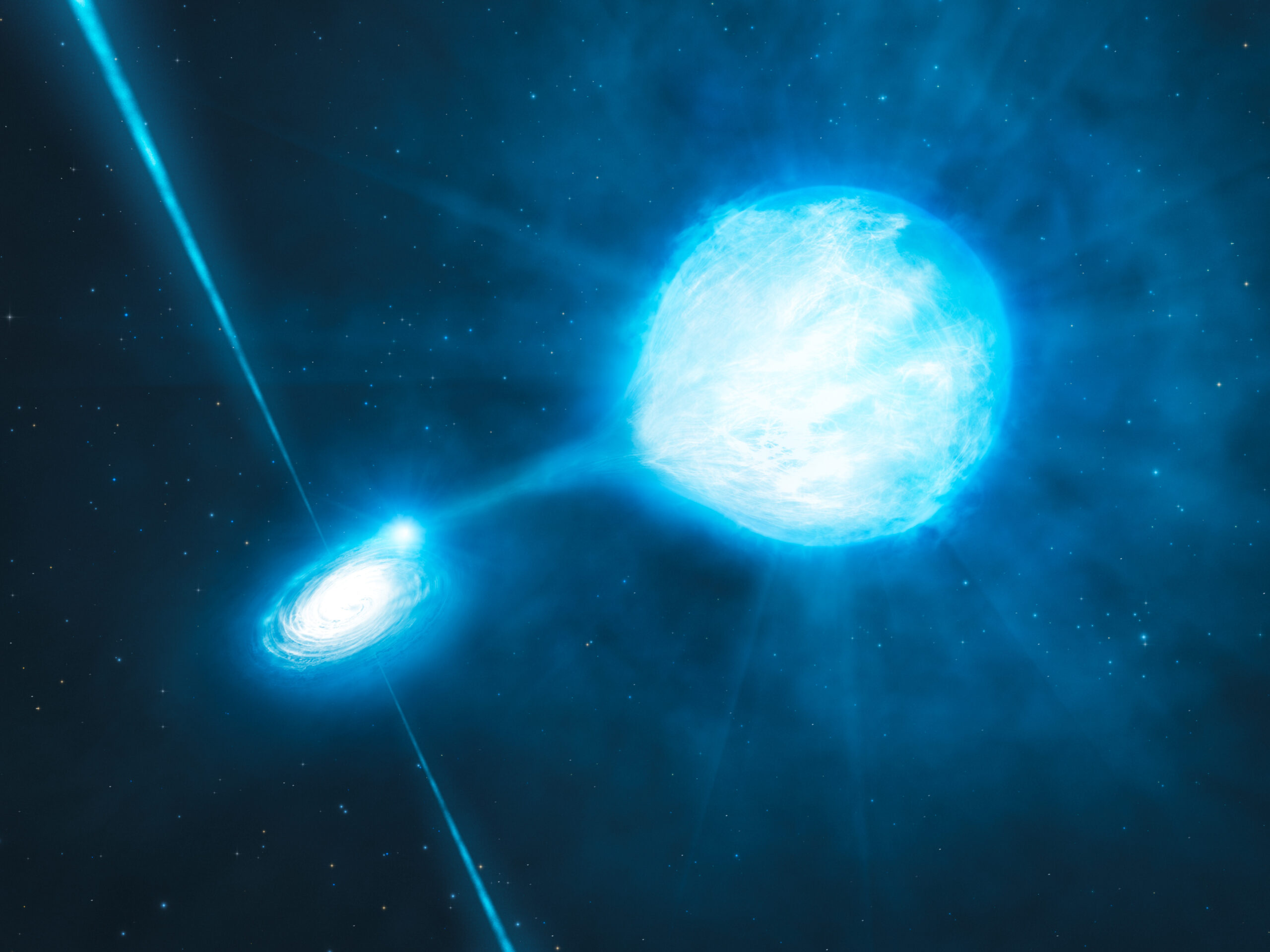

Astronomers revealed how a supermassive black hole sustains low-level activity through stellar winds in the absence of dense gas clouds.

Unveiling a Black Hole’s Unusual Diet

Unveiling a Black Hole’s Unusual Diet (Image Credits: Upload.wikimedia.org)

The supermassive black hole at the center of M60-UCD1, an ultracompact dwarf galaxy, presented researchers with a puzzle. This black hole, weighing 20 million solar masses, emitted X-rays indicative of accretion, yet the galaxy lacked substantial gas reservoirs or inflows typically required for such feeding. Instead, simulations demonstrated that winds from nearby aging stars provided the necessary material.

M60-UCD1, considered a stripped remnant of a larger galactic nucleus, hosted a dense nuclear star cluster rich in asymptotic giant branch stars. These stars shed mass through powerful winds, creating a steady supply for the black hole. Over five million years, this process formed a cold gas disk of about 1,000 solar masses within roughly 10 parsecs of the black hole.

Advanced Simulations Capture the Process

Researchers employed three-dimensional hydrodynamical simulations to model the dynamics. They tracked winds from approximately 1,500 asymptotic giant branch stars feeding the black hole’s gravitational sphere of influence. The models accounted for ram pressure from the surrounding intracluster medium, which stripped some material and moderated the flow.

Within the inner 10,000 gravitational radii, the gas disk evolved into a hot corona reaching temperatures between 10 million and 1 billion Kelvin. This corona dominated the X-ray output. The predicted accretion rate reached about 10^{-5} solar masses per year, with ram pressure reducing it by a factor of two.

- Stellar wind input from old stars in nuclear cluster.

- Cold disk formation: ~1,000 M⊕ within 10 pc.

- Accretion rate: ~10-5 M⊕/yr.

- X-ray luminosity: ~7 × 1037 erg/s.

- Corona temperature: 107–109 K.

Aligning Theory with Telescope Data

The simulated X-ray luminosity of roughly 7 × 10^{37} erg per second matched observations from the Chandra X-ray Observatory. This consistency supported the wind-fed model over alternatives like tidal disruption events or binary companions. The study also addressed H-alpha emissions potentially linked to the accretion disk.

Ram pressure effects proved crucial, as they prevented excessive buildup and kept accretion rates low. Without this, luminosities would exceed detected levels. The findings explained why similar ultracompact dwarfs show faint X-ray sources without bright active galactic nuclei.

Implications for Distant Black Holes

This mechanism offered a new explanation for low-luminosity accretion in environments starved of gas. Ultracompact dwarfs, often relics of stripped galaxies, might commonly host wind-fed black holes. The research highlighted how ambient pressures regulate growth, providing a template for other systems.

Future observations could test predictions, such as disk temperatures and emission spectra. The model extended to LINER galaxies, where stellar winds might power weak nuclear activity.

Key Takeaways:

- Wind-fed accretion sustains SMBHs in gas-poor dwarfs like M60-UCD1.

- Simulations predict observed X-ray levels precisely.

- Ram pressure balances inflow, preventing overfeeding.

These insights reshaped understanding of black hole nutrition in dense clusters, showing survival hinges on stellar exhalations. What mechanisms do you think dominate black hole growth in the early universe? Tell us in the comments.