Life on Earth started long before the giants we usually think about roamed the planet. Millions and even billions of years ago, creatures faced hostile conditions you can barely imagine. Scarce food, violent weather swings, and predators lurking in every shadow.

Survival back then required more than luck. It demanded clever tricks embedded directly into biology. These adaptations often seem almost alien when you first learn about them. Some of the wildest survival mechanisms emerged during Earth’s earliest chapters, shaping how life would evolve for eons to come. Let’s dive into seven of these fascinating evolutionary wonders.

The Amniotic Egg Revolution

Picture this: life needed to break free from water, yet embryos required a watery environment to develop, so the amniotic egg evolved with a sac containing the developing reptile in its watery world, a yolk sac providing nutrients, and a tough membrane covering that allowed gas exchange while preventing water loss. This breakthrough changed everything. Fish and amphibians remained tied to laying their eggs in water because they never developed adaptations to lay eggs on land, whereas reptiles, dinosaurs, birds, and mammals could all lay eggs on land thanks to these specialized sacs.

Think about how radical this was. Suddenly, entire continents became accessible nurseries. Animals no longer needed to huddle near ponds or streams just to reproduce. The evolution of amphibians marked the first vertebrates venturing onto land, transitioning from water to terrestrial habitats around three hundred fifty million years ago. The amniotic egg essentially turned land into a viable home for countless species that followed. Without it, you wouldn’t see the diversity of reptiles, birds, or even mammals that eventually led to us.

Hyperthermophile Energy Systems

Here’s something that might surprise you. All life forms are powered by proton concentration differences across cells’ membranes, suggesting that earliest living cells harvested energy similarly and that life arose in an environment where proton gradients were the most accessible power source. Recent studies trace the origin of life back to deep-sea hydrothermal vents, which are porous geological structures produced by chemical reactions between solid rock and water, where alkaline fluids from Earth’s crust flow toward more acidic ocean water, creating natural proton concentration differences remarkably similar to those powering all living cells.

The position of hyperthermophiles in the phylogenetic tree provides evidence that the last common ancestor was a hyperthermophile, and these organisms are known to survive deep-freezing at negative one hundred forty degrees Celsius, meaning they could have survived temperatures associated with transfer to other planets through cold space. Imagine organisms so resilient that extreme heat and cold barely faze them. This adaptation wasn’t just about surviving harsh conditions. It laid the foundation for how every cell on Earth would eventually generate power.

Trilobite Compound Eyes

The Cambrian period is characterized by rapid diversification of animal life, including early sponges, jellyfish, and arthropods like trilobites, which thrived for over three hundred million years before extinction. What made trilobites so successful for such an incredibly long stretch? Their eyes, for one thing. These ancient arthropods developed compound eyes that gave them a serious survival edge in prehistoric seas.

Trilobites measuring six to seven inches long were the largest animals in early seas, with some being oval and smooth while others had goggle eyes and spiny shells made of several sections. Those “goggle eyes” were actually complex visual systems that could detect movement and light from multiple angles simultaneously. For a creature crawling along ancient ocean floors, this meant spotting both predators and prey with remarkable efficiency. Honestly, it’s hard to overstate how revolutionary good vision was in that era. While other creatures fumbled in murky waters, trilobites saw the world in ways that kept them dominant for hundreds of millions of years.

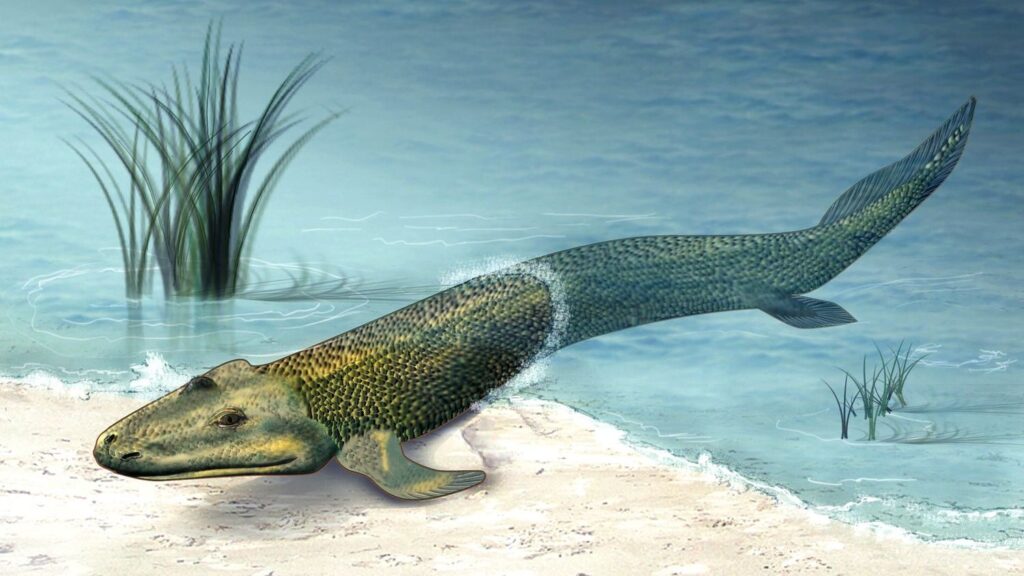

Tiktaalik’s Weight-Bearing Fins

Fossils from Arctic Canada suggest that Tiktaalik grew to lengths of three meters, and this huge size combined with large jaws full of needle-like teeth, a mobile neck, and eyes on top of its head suggests it was a predator specially adapted for hunting fish in shallows. Yet what really sets this creature apart is something underneath. Unlike most other fish, Tiktaalik had robust fins that could support its weight outside water, attached to highly mobile joints, and this combination allowed Tiktaalik and others of its kind to experiment with life on land.

This adaptation sounds simple, but it was transformative. Weight-bearing fins essentially served as proto-limbs. Where Tiktaalik falls on the vertebrate family tree is debated, but there’s no denying it lived during an important time in the evolution of four-limbed animals. Imagine a fish doing push-ups on a riverbank. That’s basically what Tiktaalik could manage, and from that humble beginning, all land vertebrates eventually emerged. Every time you take a step, you’re using a body plan that Tiktaalik helped pioneer.

Agnatha’s Primitive Teeth Structures

The oldest fossils of jawless fish, called the Agnatha, are about four hundred seventy million years old, and modern jawless lampreys and hagfish are most closely related to ancient Agnatha from the Ordovician period. These early fish didn’t have jaws like we think of them. Instead, they developed something creepier and surprisingly effective. Prehistoric Agnatha attached to larger animals through whorls of teeth and rasped the flesh of hosts, with lamprey teeth being horny, sharp structures without calcium derived from skin, and because the teeth contained enamel-like proteins, they’re considered precursors to modern teeth.

Think parasitic horror movie, but millions of years ago. These rasping, tooth-like structures weren’t as advanced as true teeth, yet they worked well enough to sustain these fish for millions of years. More advanced Agnatha that developed in later periods are important because they suggest when evolution of mineralized teeth, bone, body armor, eyes, and paired limbs occurred. It’s wild to think that your own teeth have evolutionary roots in these ancient, jawless parasites clinging to bigger fish.

RNA Self-Replication

Small RNAs can catalyze all the chemical groups and information transfers required for life, and RNA both expresses and maintains genetic information in modern organisms while its components are easily synthesized under early Earth conditions. This is where things get really primordial. Before DNA, before complex cells, there was RNA doing double duty as both information storage and catalyst. RNA replicase can both code and catalyze further RNA replication, meaning it is autocatalytic, and some catalytic RNAs can link smaller RNA sequences together, enabling self-replication, with natural selection favoring the proliferation of such autocatalytic sets.

Let’s be real: this is life at its most stripped-down and elegant. Self-assembly of RNA may occur spontaneously in hydrothermal vents, and a preliminary form of tRNA could have assembled into a replicator molecule, which when it began to replicate may have had all three mechanisms of Darwinian selection: heritability, variation, and differential reproduction. RNA essentially bootstrapped itself into existence, and from there, all the complexity of life followed. It’s one of those adaptations that feels almost like magic, even though it’s grounded in chemistry.

Proton Gradient Harnessing

The mechanism of ATP synthesis involves a closed membrane with ATP synthase enzyme embedded, where the energy to release strongly bound ATP originates in protons moving across the membrane, and in modern cells those proton movements are caused by pumping ions across the membrane to maintain an electrochemical gradient, though in first organisms the gradient could have been provided by the difference in chemical composition between flow from a hydrothermal vent and surrounding seawater. This adaptation is fundamental to every living cell today.

Studies suggest that in the earliest stages of life’s evolution, chemical reactions in primitive cells were likely driven by non-biological proton gradients, and cells later learned to produce their own gradients and escaped the vents to colonize the rest of the ocean and eventually the planet. What’s remarkable is how this ancient power source never got replaced. Life found something that worked billions of years ago and stuck with it. Every breath you take, every muscle you move, relies on proton gradients doing their thing at the cellular level. It’s a testament to how effective this early adaptation truly was.

Conclusion

These seven adaptations reveal something profound about life’s journey on Earth. From eggs that freed animals from water to molecular machines harnessing chemical gradients, evolution didn’t just stumble forward randomly. It crafted solutions so effective that many still underpin biology today. wasn’t just about survival. It was about innovation on a scale that’s hard to fully grasp.

What strikes you most about these ancient tricks? Honestly, I think it’s humbling to realize that the foundations of our own existence were laid billions of years ago by creatures we’d barely recognize. Did any of these surprise you as much as they surprised me?