When you wander through the halls of a natural history museum, marveling at towering Tyrannosaurus rex skeletons or the impressive wingspan of a Quetzalcoatlus, have you ever wondered what you’re looking at? Are these the actual fossilized remains of creatures that lived millions of years ago, or something else entirely? The answer is more complex—and fascinating—than most visitors realize. Museum dinosaur displays are scientific recreations that combine art, paleontology, and materials science to bring prehistoric creatures to life. Let’s uncover what museum dinosaur exhibits are made of, how they’re created, and why distinguishing between original fossils and replicas matters in both scientific and educational contexts.

The Rarity of Original Fossils

Genuine dinosaur fossils are exceedingly rare and precious scientific specimens. When an animal died millions of years ago, the conditions had to be just right for fossilization to occur—the remains needed to be buried quickly in sediment that lacked oxygen and contained the right minerals. Even then, only the hardest parts of the organism, typically bones and teeth, had a chance of becoming fossilized. Complete or nearly complete dinosaur skeletons are extraordinary treasures in the paleontological world. The famous T. rex specimen nicknamed “Sue” at Chicago’s Field Museum is estimated to be about 90% complete—an exceptional case that represents the exception rather than the rule. Most dinosaur species are known from much more fragmentary remains, often just a handful of bones representing less than 20% of the complete skeleton.

The Weight and Fragility Problem

Original fossilized dinosaur bones present significant practical challenges for museum display. These specimens are typically extremely heavy, having undergone mineralization where the original organic material was replaced by mineral, making complete skeletons difficult to mount safely. A single fossil vertebra from a large sauropod might weigh hundreds of pounds, with a complete skeleton potentially weighing several tons. Additionally, fossils remain surprisingly fragile despite their stone-like nature. They can crack, chip, or break entirely under their weight when removed from the surrounding rock matrix that supported them for millions of years. The valuable scientific information contained in these specimens is too precious to risk in public displays, especially considering that most fossils are one-of-a-kind records of extinct species that cannot be replaced if damaged. These practical considerations drive museums to seek alternative display solutions that protect the original material while still educating the public.

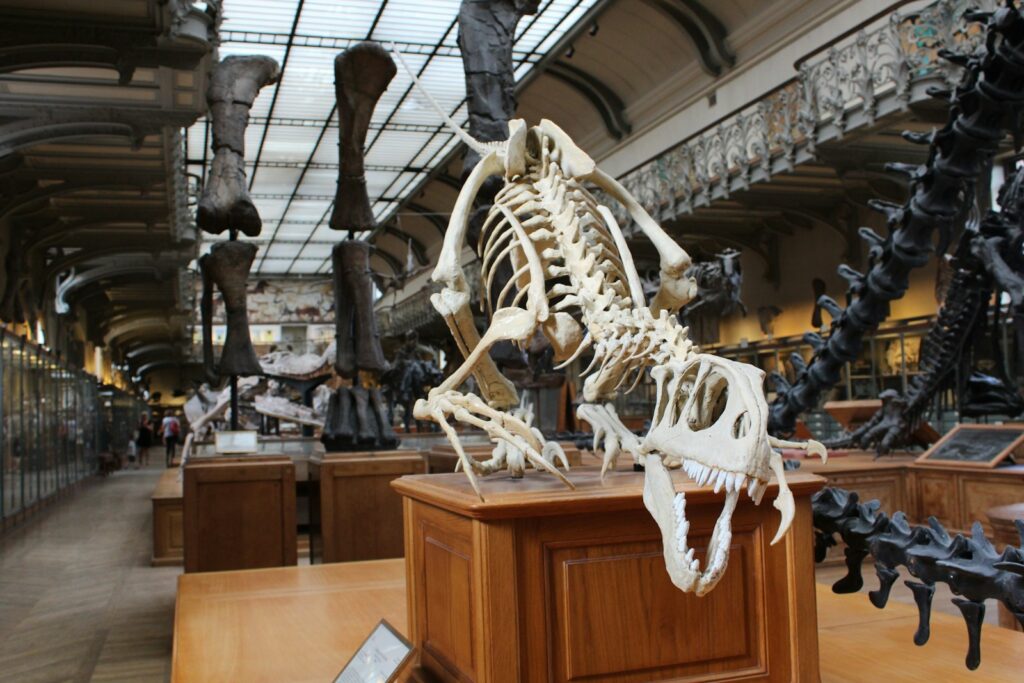

The Art of Fossil Casting

Fossil casting is a sophisticated process that creates faithful replicas of original specimens. It begins with making a mold of the original fossil using silicone rubber or similar flexible materials that capture even microscopic details of the bone surface. These molds are then filled with materials like fiberglass resin, urethane, or epoxy—lightweight alternatives that mimic the appearance of real fossils. Skilled museum preparators and artists meticulously paint the casts to match the coloration and texture of the original specimens, often adding subtle details like weathering patterns or mineral staining seen in the originals. The greatest advantage of casts is that they can be mounted in dynamic, lifelike poses that would be impossible with fragile, heavy original material. This process allows museums worldwide to display copies of significant specimens while the originals remain safely in research collections, available for scientific study but protected from the potential damage of long-term display.

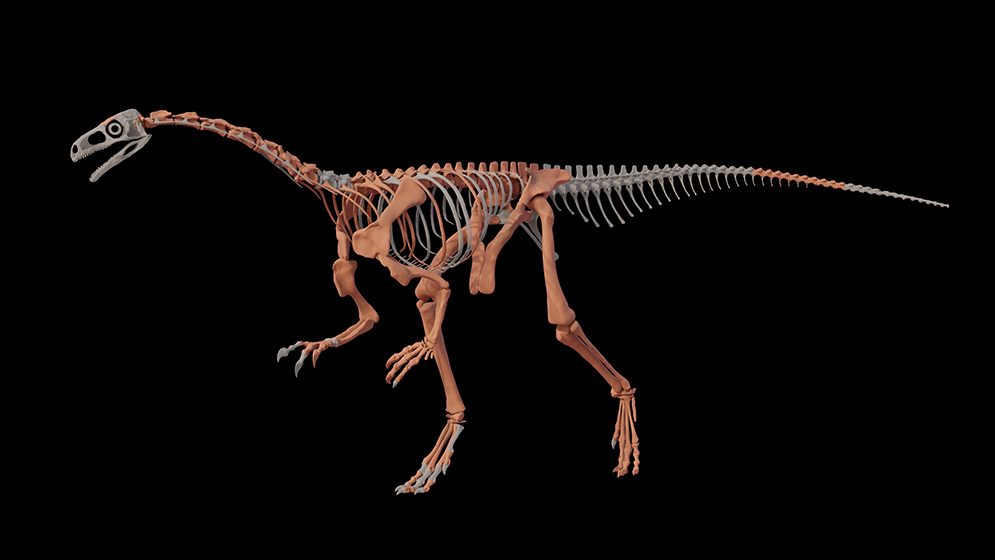

Composite Skeletons: Filling in the Gaps

Very few dinosaur skeletons are discovered with all bones intact and present, which presents a significant challenge for museum displays. To create complete-looking specimens, paleontologists and exhibit designers often create composite skeletons. This involves combining casts of bones from multiple individuals of the same species to create a single, complete-looking display. When certain bones remain undiscovered for a species, museums employ different strategies to fill these gaps. They might create mirror-image copies of bones from the opposite side of the body (if those exist), scale appropriately-shaped bones from closely related species, or sculpt entirely new bones based on scientific inference about the animal’s anatomy. These educated reconstructions are based on comparative anatomy with related species and our understanding of functional morphology—how skeletal features relate to movement and biological function. While this practice helps create more complete and visually impressive displays, good museums indicate which parts of a skeleton are original, which are casts, and which are speculative reconstructions.

3D Printing: The New Frontier

The advent of 3D printing technology has revolutionized the creation of museum displays over the past decade. This technology allows for the digital scanning of original fossils at extremely high resolution, capturing details as small as a fraction of a millimeter. These digital models can then be manipulated, scaled, and printed in various materials ranging from lightweight plastics to more dense resins that better mimic the weight and feel of actual fossils. The advantages of 3D printing for museums are numerous—digital models can be easily shared between institutions, allowing rare specimens to be replicated around the world for both display and research purposes. Damaged or fragmented fossils can be digitally repaired or completed based on scientific inference. Perhaps most importantly, 3D printing allows museums to experiment with different postures and configurations without risking original material, testing hypotheses about how these animals might have moved and carried themselves in life. Museums like the Smithsonian Institution have embraced this technology to create entire skeletal displays that would have been impossible using traditional methods.

Mixed Media Displays

Modern museum dinosaur exhibits frequently employ a strategic mix of original fossils and reproductions to balance scientific authenticity with educational impact. In these mixed displays, museums often place a few select original fossils, typically smaller, more stable specimens like teeth, claws, or smaller bones, in protective cases near the mounted skeleton. These original specimens allow visitors to see actual fossilized material, while the complete skeleton (usually made of casts) provides the dramatic visual impact that helps people understand the animal’s overall form and size. This approach offers the best of both worlds: the authenticity of real fossil material and the comprehensive educational value of complete skeletal mounts. The American Museum of Natural History in New York employs this technique in many of its dinosaur halls, where visitors can compare actual fossil material with the reconstructed skeletons. These mixed media displays represent a thoughtful compromise between preservation concerns and educational objectives.

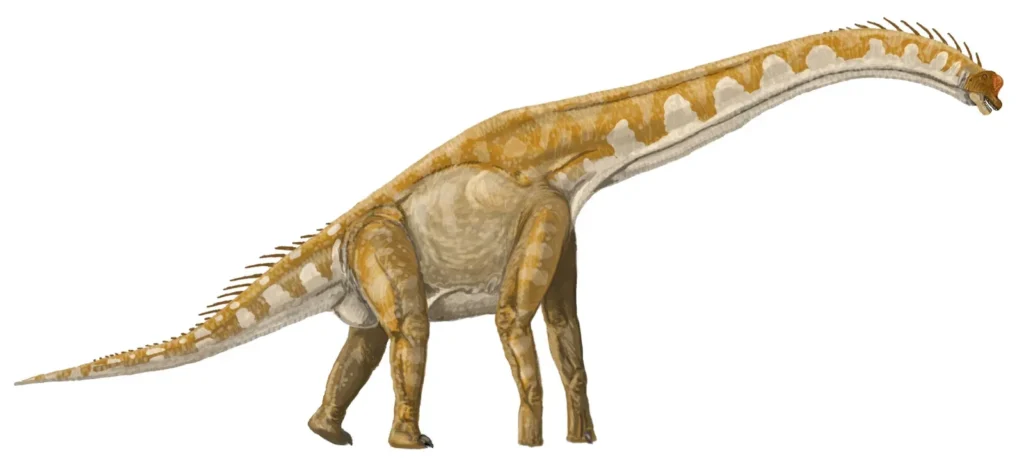

The Skin Game: Beyond Bones

Creating lifelike reconstructions that go beyond bare skeletons involves even more speculative scientific work and artistic interpretation. When museums display fleshed-out models of dinosaurs with skin, muscles, and other soft tissues, these reconstructions are based on multiple lines of evidence. Rare skin impressions and soft tissue preservation provide some direct evidence of external appearance for a few species. Comparative anatomy with living relatives (primarily birds and crocodilians) offers clues about muscle attachment points and likely body contours. The positioning of bones and joints suggests how muscles and other soft tissues might have been arranged. Scientific disciplines like biomechanics help researchers understand how these animals moved and functioned, informing how their muscles would have been structured. Despite these scientific approaches, significant artistic interpretation remains necessary, particularly regarding details like skin color, texture, and patterns, where direct evidence is often lacking. These full-bodied reconstructions represent our best current understanding of how these animals appeared in life, but they should be understood as scientific hypotheses visualized through art rather than definitive representations.

The Ethical Dimension: Transparency in Displays

Ethical museum practice demands clear communication about what visitors are viewing in dinosaur exhibits. Responsible institutions make efforts to indicate which elements are original fossils and which are reproductions through informational signage, different coloration of replica materials, or other visual cues. This transparency serves both scientific integrity and educational honesty. When museums fail to clearly distinguish between original material and reproductions, they risk misleading visitors about the nature of the scientific evidence for these extinct animals. There’s also an important ethical dimension regarding the source of original fossils in museum collections. In recent decades, museums have become increasingly concerned with ensuring that specimens were collected legally and ethically, with proper permissions from landowners and governments. The fossil trade has unfortunately seen significant issues with poaching and illegal collection, particularly in countries with rich fossil resources but limited means to protect them. Leading museums now work to ensure their collections, even when acquired in the past, have proper provenance and were collected with appropriate scientific protocols.

Historical Evolution of Museum Displays

The presentation of dinosaur skeletons in museums has undergone dramatic changes over the past century, reflecting evolving scientific understanding and exhibition techniques. Early dinosaur mounts from the late 19th and early 20th centuries often featured original fossils arranged in what we now know were anatomically incorrect postures—Diplodocus and other sauropods dragging their tails, Tyrannosaurus standing upright like a tripod. These early displays typically used heavy steel frameworks that often damaged the original fossils as metal bolts and rods were drilled directly into the specimens. By the mid-20th century, museums began using more fossil casts while better protecting original specimens, but many outdated poses remained. The “Dinosaur Renaissance” of the 1970s and 1980s dramatically changed scientific understanding of dinosaurs as active, dynamic animals rather than slow, lumbering reptiles. This scientific revolution prompted museums worldwide to redesign their exhibits with more accurate, active poses—tails held aloft, bodies balanced horizontally rather than vertically. Modern mounting techniques use minimally invasive supports, often custom-designed around digital scans of the bones to provide support without damaging specimens, representing a significant improvement in both scientific accuracy and conservation practices.

Research Collections vs. Display Specimens

Many visitors don’t realize that the dinosaur skeletons they see on display represent just a small fraction of a museum’s total fossil collection. Major natural history museums typically house vast research collections that remain behind the scenes, accessible primarily to scientists and researchers rather than the general public. These research collections contain the majority of a museum’s original fossil material, carefully preserved in climate-controlled environments and organized for scientific study rather than public display. The Field Museum in Chicago, for example, maintains a collection of over 500,000 fossil specimens, while only a small percentage are on public display at any given time. These behind-the-scenes collections serve as crucial scientific archives—repositories of evidence about extinct life forms that researchers from around the world can access to conduct studies on evolution, paleobiology, ancient ecosystems, and climate change. Museums balance their dual missions of public education (through displays) and scientific research (through these collections) by utilizing reproductions for much of their public-facing exhibits while preserving original material in conditions optimized for long-term conservation and research accessibility.

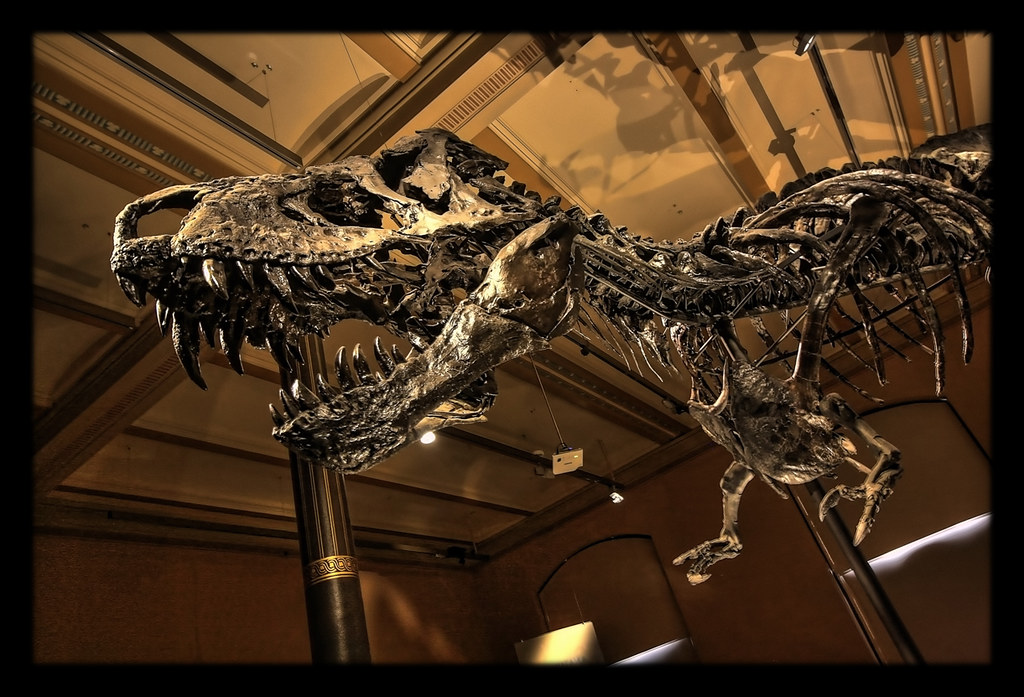

Famous Originals: The Exceptions to the Rule

While most dinosaur displays feature reproductions, some famous specimens buck this trend and showcase substantial original fossil material. Perhaps the most famous is “Sue,” the Tyrannosaurus rex at Chicago’s Field Museum, which represents one of the most complete T. rex skeletons ever discovered, at roughly 90% complete. The original fossils of Sue’s skeleton were deemed sturdy enough for public display, though even in this exceptional case, the actual skull was too heavy and valuable to mount with the skeleton—a precisely made cast is used in the display while the original skull is exhibited separately in a special case. Berlin’s Museum für Naturkunde houses the original skeleton of Brachiosaurus brancai (now classified as Giraffatitan), the tallest mounted dinosaur skeleton in the world that includes substantial original material. London’s Natural History Museum displays the original skeleton of Diplodocus carnegii (nicknamed “Dippy”) that has become an iconic symbol of the institution since its installation in 1905, though it occasionally tours as a cast replica while the original is preserved. These exceptional displays of original material offer visitors rare opportunities to stand in the presence of actual fossilized remains of these ancient creatures, though they represent exceptions rather than the standard practice in museum exhibitions.

The Educational Value of Replicas

Far from being “fake” dinosaurs, high-quality fossil replicas serve crucial educational and scientific purposes. Accurate casts democratize access to important specimens by allowing multiple museums around the world to display copies of significant fossils that would otherwise be viewable only in a single location. This wider distribution of replicas means more people can learn from and be inspired by these discoveries without the environmental impact of excessive travel. From an educational perspective, complete skeletal mounts made from lightweight casts can be positioned in more scientifically accurate, dynamic poses that help visitors better understand how these animals moved and behaved in life. Additionally, casts can be handled for educational programs in ways that would be impossible with fragile original specimens, allowing students and visitors to engage in tactile learning experiences. Leading paleontologists recognize that well-made casts play a vital role in both public education and scientific research, particularly for comparative studies where having multiple specimens available for side-by-side examination can reveal subtle but significant variations between individuals or species.

The Future of Museum Dinosaurs

The future of dinosaur exhibits will likely be shaped by continuing technological advances in both paleontology and display techniques. Emerging technologies like CT scanning are already allowing paleontologists to examine the internal structures of fossils without damaging them, revealing previously hidden details about brain cases, sinus cavities, and other internal features. This data is increasingly being incorporated into more anatomically accurate replicas. Augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) technologies are beginning to supplement physical displays, allowing visitors to see digital reconstructions of how dinosaurs might have appeared with soft tissues, or how they might have moved through ancient environments. Some museums are experimenting with robotics and animatronics to create moving displays that demonstrate current theories about dinosaur locomotion and behavior. Despite these technological advances, physical specimens—whether original or replica—will likely remain central to museum experiences, as there’s simply no substitute for standing next to a life-sized Tyrannosaurus skeleton and physically experiencing its scale and presence. The most effective future exhibits will likely combine traditional specimens with digital enhancements, creating multi-sensory educational experiences that engage visitors while accurately representing our ever-evolving scientific understanding of these fascinating prehistoric creatures.

Conclusion

The dinosaur skeletons that capture our imagination in museum halls represent a sophisticated blend of science, art, and practical exhibition techniques. While most displays feature relatively few original fossils, the casts, composites, and reconstructions we see are far from mere props—they are scientifically rigorous representations created with extraordinary attention to detail. The use of reproductions allows museums to fulfill their dual missions of preserving irreplaceable fossil specimens for scientific research while also creating educational exhibits that inspire wonder and curiosity about Earth’s prehistoric past. By understanding what we’re looking at when we visit these exhibits, we can better appreciate both the ancient animals themselves and the remarkable scientific detective work that brings them back to life for modern audiences. Whether made of original fossil material or the highest quality replicas, museum dinosaurs continue to serve as ambassadors from the deep past, connecting us to a world that existed long before humans walked the Earth.