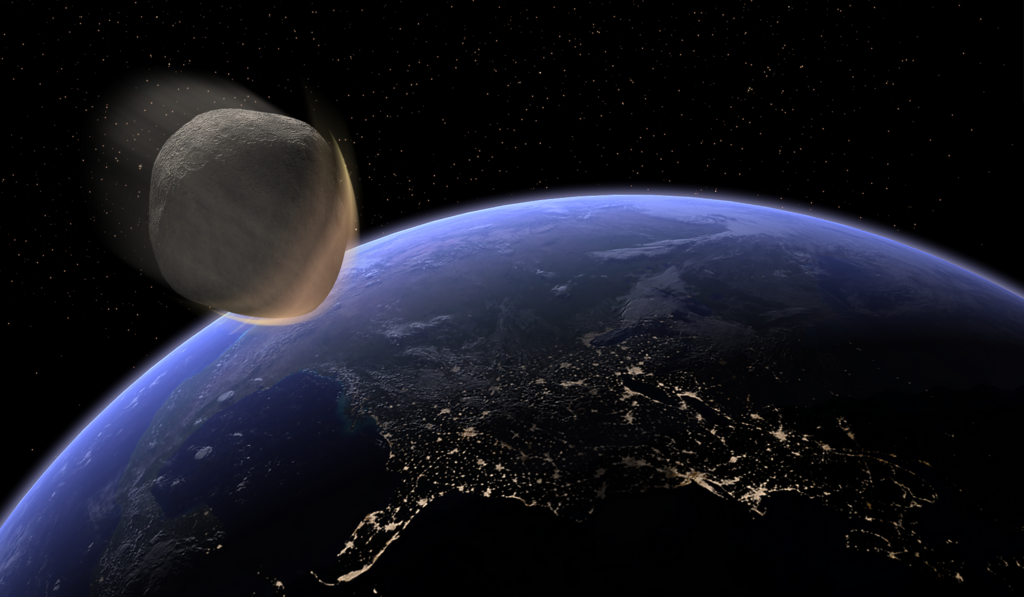

When the asteroid struck Earth 66 million years ago, it marked the end of the non-avian dinosaurs but opened evolutionary pathways for survivors. Among these survivors, birds—the direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs—would diversify into countless forms. Some of these evolutionary experiments produced giants like the terror birds (Phorusrhacids) that dominated South American landscapes for millions of years. These formidable predators raise fascinating questions about evolutionary succession: could these and other extinct bird lineages be considered the true ecological successors to dinosaurs? This article explores the biological, ecological, and evolutionary connections between extinct predatory birds and their dinosaurian ancestors, examining how the dinosaur legacy continued long after the K-Pg extinction event.

The Dinosaur-Bird Connection: A Brief History

The relationship between dinosaurs and birds represents one of paleontology’s greatest revelations. Since the discovery of Archaeopteryx in 1861, evidence has mounted showing that birds are not merely related to dinosaurs—they are dinosaurs, specifically descended from small, feathered theropods. Numerous fossil discoveries from China’s Liaoning Province have revealed the presence of feathers on many non-avian dinosaurs, blurring the once-clear line between the groups. Modern phylogenetic analyses consistently place birds within the maniraptoran theropods, alongside velociraptor and other dromaeosaurids. Birds are essentially the only dinosaur lineage that survived the K-Pg extinction event, making them living dinosaurs in the most literal taxonomic sense. This evolutionary heritage provided birds with adaptations—from air sacs to rapid growth rates—that would later enable some lineages to evolve into impressive predators like terror birds.

Terror Birds: The Giants of the Cenozoic

The Phorusrhacids, commonly known as terror birds, emerged in South America during the Paleocene and diversified into apex predators that ruled for over 60 million years. The largest species, like Titanis and Kelenken, stood up to 3 meters (10 feet) tall with massive, axe-like beaks designed for delivering killing blows to prey. Unlike modern predatory birds that use talons as their primary weapons, terror birds were flightless and relied on powerful legs for running down prey and their enormous skulls for dispatching victims. Their reign coincided with a period when South America existed as an island continent, allowing these avian predators to fill ecological niches that might otherwise have been occupied by mammalian carnivores. While anatomically birds, terror birds evolved a body plan and predatory lifestyle reminiscent of the theropod dinosaurs that preceded them, suggesting a form of ecological succession that bridged the Mesozoic and Cenozoic eras.

Evolutionary Convergence With Their Dinosaurian Ancestors

When examining terror birds alongside their dinosaurian ancestors, striking parallels emerge that go beyond their shared evolutionary heritage. The body plan of large phorusrhacids converged remarkably with that of certain theropod dinosaurs, particularly the more lightly built carnivores like ornithomimids and some dromaeosaurids. Both groups evolved powerful hindlimbs for rapid locomotion, reduced forelimbs, and large skulls with powerful jaw musculature. Terror birds’ predatory behavior likely resembled that of many medium-sized theropods, using speed and powerful killing bites rather than talons or claws. This convergence wasn’t merely coincidental—it represented evolution repeatedly finding optimal solutions for terrestrial predation. The similarity was so pronounced that early terror bird fossils were occasionally misidentified as dinosaur remains, highlighting how these birds had readopted aspects of their ancestors’ body plan to solve similar ecological challenges in the post-dinosaur world.

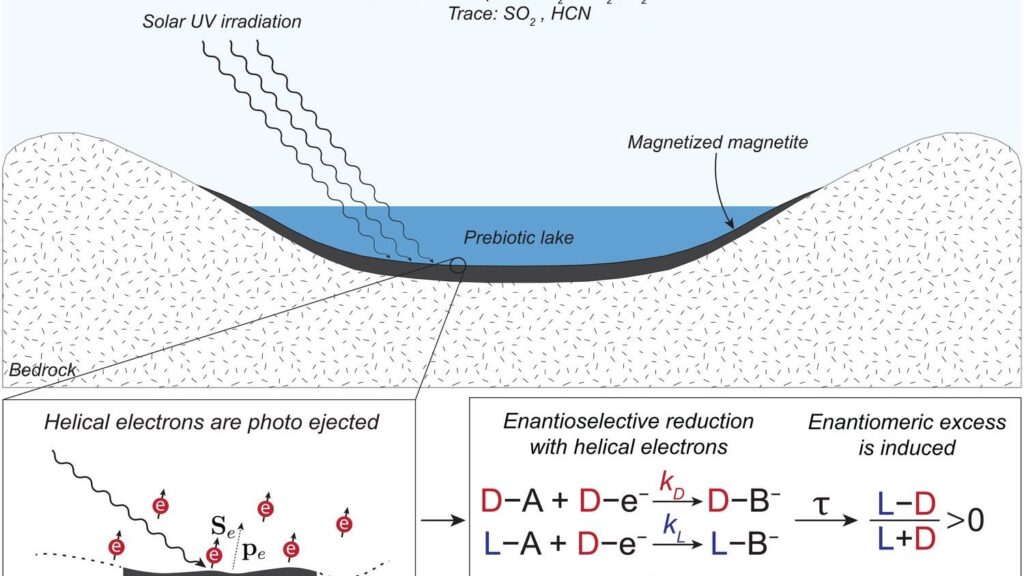

Ecological Succession After the K-Pg Extinction

The asteroid impact that ended the Mesozoic created ecological vacancies across the planet, particularly in predator niches formerly occupied by theropod dinosaurs. While mammals would eventually dominate many of these roles globally, South America’s isolation allowed birds to experiment with novel adaptations. Terror birds emerged as apex predators in this laboratory of evolution, filling niches reminiscent of those once occupied by medium to large theropods. They weren’t alone in this avian resurgence—other bird groups like the related bathornithids in North America and the unrelated gastornithids in Europe and North America also evolved into large flightless forms, suggesting a broader pattern of birds temporarily reclaiming dinosaurian ecological territory. This represents a fascinating case of ecological succession, where descendants of one group (theropod dinosaurs) re-evolved to fill niches similar to those of their ancestors after an extinction event, demonstrating the cyclical nature of evolutionary opportunity.

Dromornithids: Australia’s Thunder Birds

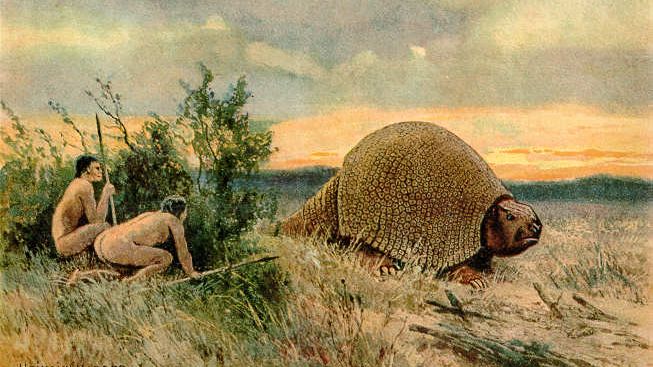

Australia produced its own lineage of giant birds known as dromornithids or “thunder birds,” with the largest genus Dromornis standing up to 3 meters tall and weighing an estimated 500 kg. Unlike the predatory terror birds, most dromornithids were likely herbivores or omnivores, using their massive beaks to process tough plant material or occasionally small prey. These birds evolved in isolation on the Australian continent from the Paleocene to the Pleistocene, thriving for over 60 million years. Their ecological role differed from terror birds, more closely resembling giant herbivorous dinosaurs like ornithopods in their niche, albeit on a smaller scale. Dromornithids demonstrate how birds diversified to fill multiple dinosaurian niches after the extinction event, not just predatory ones. Their eventual extinction, which coincided with human arrival in Australia, marked the end of another experiment in avian gigantism that had succeeded dinosaurs in isolated ecosystems.

Elephant Birds: Madagascar’s Giant Grazers

Madagascar’s elephant birds (Aepyornithidae) represent another remarkable case of avian gigantism that emerged in the Cenozoic era. These massive ratites produced the largest birds known to have existed, with Vorombe titan reaching heights of over 3 meters and weights exceeding 730 kg—heavier than many small dinosaurs. Like the dromornithids, elephant birds were primarily herbivorous, using their massive beaks to browse vegetation in Madagascar’s diverse ecosystems. They survived until remarkably recent times, with the last specimens disappearing only around 1,000 years ago following human colonization of Madagascar. While not predators like terror birds, elephant birds demonstrate how birds could evolve body sizes approaching those of smaller dinosaurs when ecological conditions permitted. Their existence on an isolated island—free from mammalian competitors and predators—allowed this experiment in avian gigantism to proceed, creating a unique ecological succession where birds rather than mammals became the dominant large-bodied herbivores.

Ecological Niche Replacement Versus True Succession

When considering whether terror birds and other extinct avian giants constituted true dinosaur successors, we must distinguish between simple niche replacement and evolutionary succession. Terror birds, despite their size and predatory lifestyle, hunted differently than most theropod dinosaurs, relying on powerful downward strikes from their beaks rather than grasping with clawed hands. Similarly, elephant birds and dromornithids processed vegetation differently than ornithopods or sauropods had done. These differences highlight that while birds filled some dinosaurian niches, they did so with modified anatomies and behaviors specific to their avian heritage. True succession implies not just occupying similar ecological roles but doing so as direct evolutionary descendants. By this definition, terror birds and other giant extinct birds represent both ecological replacements and true successors—they filled niches left vacant by extinct dinosaurs while themselves being surviving dinosaur descendants that had adapted to new Cenozoic conditions.

The Missing Giants: Why Birds Never Reached Dinosaur Sizes

Despite producing some impressive giants, birds never approached the size of the largest dinosaurs, with even the heaviest elephant birds weighing less than a tenth of medium-sized sauropods. Several factors likely constrained avian gigantism compared to their dinosaurian ancestors. The avian respiratory system, while highly efficient, works best with hollow, lightweight bones that limit maximum body size due to structural constraints. Flight adaptations, even in lineages that later became flightless, imparted developmental limitations on size increase. Additionally, birds have higher metabolic rates than most reptiles, requiring greater food intake relative to body size. The Cenozoic world also presented different selective pressures, with mammals providing competition that hadn’t existed during the Mesozoic. Perhaps most significantly, the compressed evolutionary timeframe—birds had only 66 million years compared to the 165+ million years non-avian dinosaurs had to evolve gigantism—limited how large birds could become before most giant lineages went extinct.

The Role of Competition with Mammals

The rise of mammalian predators played a crucial role in the evolutionary history of giant flightless birds. Terror birds thrived primarily in South America during its island phase, when the continent lacked large mammalian carnivores. Their decline coincided with the Great American Interchange following the formation of the Panama land bridge, which allowed North American predators like saber-toothed cats and bears to move south. Similar patterns occurred elsewhere—gastornithids declined as mammalian predators diversified in Europe and North America, while dromornithids persisted in Australia until mammals became more dominant. This competitive relationship highlights a key difference between non-avian dinosaurs and their avian descendants: dinosaurs evolved in ecosystems where they were the dominant large vertebrates, while most giant birds evolved in temporary ecological vacancies before mammalian competition intensified. The exceptions—like elephant birds on Madagascar—demonstrate that in the absence of mammalian competitors, birds could maintain dinosaurian successor roles for much longer periods.

The Island Rule and Avian Gigantism

Many of the most spectacular giant birds evolved on islands or isolated continents, following a pattern known as the “island rule,” where certain animals tend toward larger sizes in insular environments. Terror birds dominated South America during its island phase, elephant birds evolved on Madagascar, dromornithids on Australia, and moas in New Zealand. This pattern suggests that avian gigantism—and thus the most dinosaur-like ecological succession—occurred primarily where birds faced reduced competition from mammals. Islands often lack large predators, allowing prey species to evolve larger sizes, and simultaneously permitting birds to evolve into predator or large herbivore roles that might otherwise be filled by mammals. The island rule effectively created evolutionary laboratories where birds could more fully explore size increases and ecological roles reminiscent of non-avian dinosaurs. This pattern further supports the view that birds represented true dinosaurian successors, but primarily in contexts where mammalian competition was limited.

Modern Analogues: Are Cassowaries Living Terror Birds?

Among living birds, the cassowary most closely resembles terror birds in its ecological role and physical capabilities. Standing up to 2 meters tall and weighing up to 60 kg, the cassowary possesses a bony casque on its head, powerful legs with dagger-like claws, and a formidable disposition that has earned it a reputation as one of the world’s most dangerous birds. Cassowaries have been documented killing humans with slashing kicks capable of disemboweling predators, a hunting method quite different from the head-striking terror birds but equally effective. These birds evolved in New Guinea and northern Australia, regions where large mammalian predators were historically limited. While much smaller than terror birds, cassowaries demonstrate how modern birds can still occupy predator-like niches in certain ecosystems, representing a diluted but still-present echo of the dinosaurian legacy. Their continued existence suggests that the succession from dinosaurs to predatory birds never completely ended, but persists in modified form in limited ecological contexts.

The Evolutionary Legacy: Birds as Living Dinosaurs

The question of whether terror birds and other extinct avian giants were dinosaur successors ultimately depends on perspective. From a cladistic viewpoint, all birds—from hummingbirds to terror birds to ostriches—are dinosaurs by definition, making them not merely successors but actual surviving members of the dinosaur clade. Their DNA carries the legacy of 230+ million years of dinosaur evolution, modified but unbroken. From an ecological perspective, terror birds and their kin temporarily reclaimed some niches that had been occupied by their non-avian dinosaur ancestors, representing true ecological succession in certain environments. The gradual replacement of these giant birds by mammals doesn’t diminish this accomplishment but highlights the dynamic nature of evolutionary succession. Perhaps most significantly, the story of terror birds and other giant extinct birds demonstrates evolution’s cyclical nature—how descendants can re-evolve characteristics reminiscent of their ancestors when ecological opportunities arise, creating temporal rhymes in Earth’s biological history.

Conclusion: Successors, Continuations, or Something In Between?

Terror birds and other extinct avian giants represented a fascinating evolutionary experiment in which dinosaur descendants temporarily reclaimed ecological territory once held by their ancestors. They were simultaneously dinosaurian successors and continuations—filling similar niches while themselves being surviving dinosaur descendants. Their ultimate decline in the face of mammalian competition doesn’t diminish their evolutionary significance but illustrates the contingent nature of succession in the aftermath of mass extinctions. The world after the asteroid impact represented not a complete transition from dinosaur to mammal dominance, but a complex mosaic where dinosaur descendants in the form of birds continued to play important roles, sometimes dominant ones in certain ecosystems. While mammals ultimately claimed most large-bodied terrestrial niches, the terror birds, elephant birds, and their kin remind us that evolution’s path is rarely straightforward. They stand as testimony to the resilience and adaptability of the dinosaur lineage, which continues today in the form of more than 10,000 bird species worldwide—dinosaurs that still dominate the skies even as their giant ground-dwelling ancestors have passed into extinction.