For millions of years, dinosaurs ruled Earth as the dominant land animals, evolving diverse adaptations to thrive in various environments. When we picture dinosaurs, we typically imagine them roaming across vast plains, dense forests, or swampy landscapes. However, as paleontologists continue making groundbreaking discoveries, questions arise about whether some dinosaur species might have utilized subterranean environments, especially during periods of extreme climate stress. This fascinating hypothesis challenges our traditional understanding of dinosaur behavior and survival strategies while opening new avenues for research into how these remarkable creatures might have endured environmental challenges that eventually culminated in the mass extinction event 66 million years ago.

The Underground Survival Hypothesis

The concept that dinosaurs might have ventured underground during harsh climate conditions stems from paleontological evidence and ecological parallels with modern animals. Today, many species—from desert rodents to wombats—create elaborate burrow systems to escape extreme temperatures, predators, and other environmental stressors. These underground retreats provide stable microclimates that can differ significantly from surface conditions. For dinosaurs facing dramatic climate shifts, including periods of extreme heat, cold, or the aftermath of the Chicxulub asteroid impact, underground habitats could theoretically have offered temporary refuge from unsurvivable surface conditions. This hypothesis doesn’t suggest dinosaurs lived their entire lives underground but rather that some species might have utilized subterranean spaces as survival shelters during environmental crises.

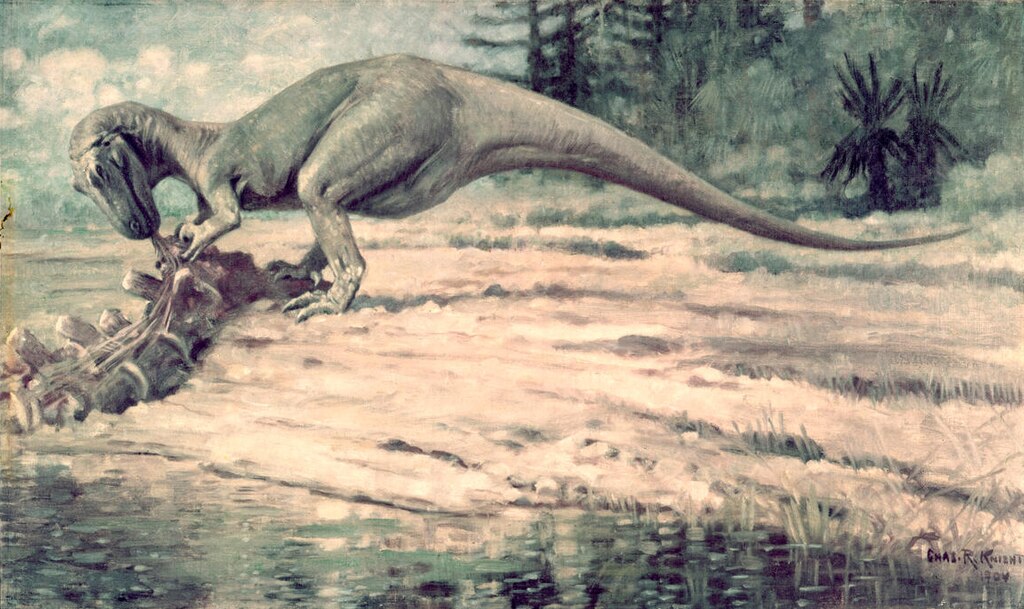

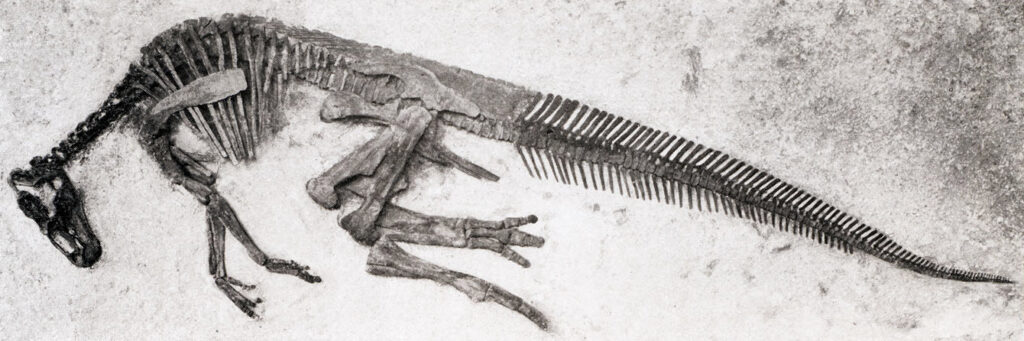

Fossil Evidence of Burrowing Dinosaurs

Remarkably, paleontologists have discovered compelling evidence that certain dinosaur species did indeed create and inhabit burrows. The most famous example comes from Montana, where researchers uncovered the remains of Oryctodromeus cubicularis, a small herbivorous dinosaur whose name means “digging runner of the lair.” Found within what appears to be an ancient burrow system, this 95-million-year-old dinosaur showed physical adaptations consistent with digging behavior, including robust shoulders and hips. Another notable discovery in Victoria, Australia, revealed burrows attributed to small polar dinosaurs that likely used underground shelters to survive the cold, dark winters of the Cretaceous polar regions. These findings demonstrate that burrowing behavior evolved independently in multiple dinosaur lineages, suggesting it offered significant survival advantages.

Anatomical Adaptations for Underground Life

For dinosaurs to effectively create and navigate underground spaces, they would need specific physical adaptations. Modern burrowing animals typically have strong forelimbs, robust shoulders, reinforced snouts, and compact bodies—features that facilitate digging and movement through confined spaces. When examining the fossil record, paleontologists have identified several dinosaur species with anatomical characteristics potentially suitable for digging activities. The aforementioned Oryctodromeus possessed a reinforced hip structure and powerful limbs that could have enabled efficient digging behavior. Similarly, certain ornithopod dinosaurs show adaptations that might have facilitated shallow burrowing or nest construction. However, it’s important to note that many large dinosaur species, particularly the massive sauropods and theropods, lacked the physical adaptations necessary for creating underground shelters and would have been physically incapable of subterranean living due to their size and body structure.

Climate Volatility During the Mesozoic Era

The Mesozoic Era, spanning approximately 252 to 66 million years ago, experienced significant climate fluctuations that could have driven adaptive behaviors in dinosaur populations. During this time, Earth underwent several warming and cooling periods, volcanic events, and regional environmental changes that would have stressed dinosaur communities. The Late Triassic extinction event, for instance, saw dramatic climate shifts linked to massive volcanic eruptions, while the Late Cretaceous featured cooling trends in some regions. These climate variations created selection pressures that favored adaptable species. Underground environments, with their more stable temperatures and humidity levels, would have provided crucial refuges during extreme weather events, seasonal temperature swings, or other environmental stressors. The thermal buffering provided by even shallow burrows could have been particularly valuable for smaller dinosaur species or juveniles with limited thermoregulatory capabilities.

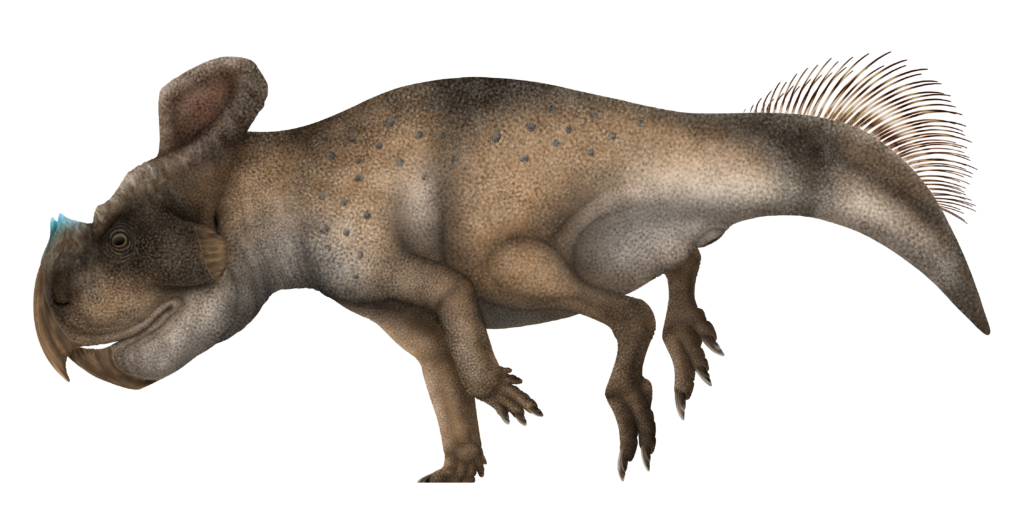

Size Constraints and Underground Possibilities

One significant limitation to the underground dinosaur hypothesis relates to the sheer size of many dinosaur species. Creating burrows large enough to accommodate medium to large dinosaurs would present enormous engineering challenges even with optimal soil conditions. The largest known burrows from the fossil record could potentially shelter dog-sized animals, making them suitable only for the smallest dinosaur species or perhaps juveniles of larger species. Consequently, if underground sheltering behaviors existed among dinosaurs, they were likely limited to smaller species weighing less than a few hundred pounds. Species like the chicken-sized Protoceratops, small dromaeosaurs, or juveniles of larger species would be the most plausible candidates for burrowing behavior. This size constraint means that while underground sheltering might have saved some dinosaur lineages during harsh climate events, it couldn’t have been a universal survival strategy across all dinosaur taxa.

Underground Nesting Behaviors

One particularly intriguing aspect of dinosaur biology that connects to potential underground activity involves nesting behaviors. Paleontologists have found extensive evidence that many dinosaur species buried their eggs, created elaborate nest structures, or utilized existing depressions in the ground for egg-laying purposes. The oviraptorid dinosaurs of Mongolia, for instance, arranged their eggs in circular patterns within shallow depressions, while some hadrosaurs appear to have created mounded nest structures using vegetation. These behaviors suggest dinosaurs recognized the benefits of moderating the temperature and humidity exposure of their eggs, a benefit that would extend to potential underground sheltering. The discovery of dinosaur nests in varied configurations demonstrates that many species actively manipulated their immediate environment to create favorable conditions for their offspring, a behavioral flexibility that could extend to seeking underground refuge during environmental stresses.

Geological Requirements for Dinosaur Burrows

For dinosaurs to create viable underground shelters, specific geological conditions would have been necessary. Ideal burrowing substrates include stable, cohesive soils that can support tunnel structures without immediate collapse, similar to the conditions favored by modern burrowing animals. During the Mesozoic Era, certain environments would have been particularly conducive to burrowing activities, including riverbanks, floodplains with stabilized soils, and forested areas with extensive root networks providing structural reinforcement. Areas with extremely rocky substrates, loose sand, or waterlogged conditions would have been prohibitive for burrow construction. The geology of formations where potential dinosaur burrows have been discovered typically features fine-grained sedimentary deposits that would have facilitated digging activities while providing the structural integrity necessary to prevent burrow collapse. These geological requirements would have limited potential burrowing sites, making underground sheltering a geographically restricted strategy even for appropriately sized dinosaur species.

Comparisons to Modern Burrowing Animals

Examining contemporary burrowing animals provides valuable insights into how dinosaurs might have utilized underground spaces. Modern burrowers like prairie dogs, wombats, and gopher tortoises create complex tunnel systems that serve multiple functions, including temperature regulation, predator avoidance, and water conservation. These burrows can be remarkably sophisticated, featuring specialized chambers for sleeping, food storage, and waste. Temperature measurements from active burrows show they can remain 10-20°F cooler than surface temperatures during summer heat and significantly warmer during winter cold. For dinosaurs facing similar environmental challenges, comparable benefits would have made burrowing behaviors highly advantageous. Additionally, modern burrowing animals typically exhibit social behaviors coordinated around their underground habitat, s—suggesting that if dinosaurs did utilize burrows, it might have influenced their social structures and community organizations in ways not readily apparent from skeletal remains alone.

The K-Pg Extinction Event and Underground Survival

The Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction event approximately 66 million years ago eliminated approximately 75% of species on Earth, including all non-avian dinosaurs. This catastrophic event, triggered by a massive asteroid impact, created conditions hostile to life across the planet, including blazing wildfires, acid rain, and a prolonged “impact winter” as atmospheric dust blocked sunlight. In this apocalyptic scenario, underground environments would have offered some protection from the immediate effects of the impact. However, the extended period of ecosystem collapse that followed would have decimated food sources even for burrowing dinosaurs. Interestingly, many creatures that did survive the extinction event—including mammals, certain reptiles, and amphibians—possessed burrowing capabilities or utilized underground shelters. This survival pattern suggests that while underground habitats provided some protection during the initial catastrophe, long-term survival depended on additional factors, including dietary flexibility, small body size, and metabolic adaptations that most dinosaur species lacked.

Technological Challenges in Identifying Ancient Burrows

Identifying and confirming dinosaur burrows in the fossil record presents significant technical challenges for paleontologists. Unlike bones, which mineralize and preserve relatively well, burrow structures can be difficult to distinguish from other geological features without specific preservation conditions. The most convincing evidence comes from cases where animal remains are found within burrow-like structures or where distinctive scratch marks and construction patterns match known burrowing behaviors. Advanced imaging technologies, including ground-penetrating radar and CT scanning, have improved researchers’ abilities to identify potential burrow structures and examine them non-destructively. Experimental archaeology, where scientists study the burrowing behaviors and resulting structures created by modern animals, also helps establish criteria for identifying ancient burrows. Despite these advances, the fossil record of burrowing behavior remains sparse compared to skeletal evidence, meaning our understanding of dinosaur underground activities is still evolving as new technologies and discoveries emerge.

Regional Variations in Burrowing Evidence

Evidence suggesting dinosaur burrowing behaviors shows interesting geographical patterns that may reflect regional environmental pressures. The most compelling discoveries of dinosaur burrows come from higher latitude environments that would have experienced more extreme seasonal temperature variations. In Montana and Alberta, fossils of small dinosaurs found in burrow-like structures suggest these animals used underground spaces to survive harsh winters. Similarly, polar dinosaurs from Australia appear to have utilized burrows to endure long periods of darkness and cold during winter months. These regional patterns suggest that underground sheltering behaviors may have evolved most prominently in areas where seasonal climate stresses created the strongest selective pressures for such adaptations. Conversely, tropical and subtropical dinosaur communities, which experienced more stable year-round conditions, show less evidence of burrowing behaviors. This geographical distribution of evidence supports the hypothesis that burrowing was an adaptive response to specific environmental challenges rather than a universal dinosaur behavior.

Future Research Directions

The question of whether dinosaurs utilized underground environments during climate shifts remains an active and evolving area of paleontological research. Several promising research directions could yield further insights into this fascinating possibility. Targeted excavations in formations representing periods of known climate stress might reveal more examples of dinosaur burrows or evidence of subterranean activity. Advanced geochemical analysis of dinosaur remains, particularly examining isotopes that serve as temperature proxies, could help identify species that experienced less temperature variation than their surface-dwelling counterparts—a potential signature of underground living. Computer modeling of dinosaur thermophysiology about underground microclimates could quantify the potential survival advantages of burrowing behaviors during extreme climate events. Additionally, comprehensive comparative studies of bone microstructure between known burrowing animals and candidate dinosaur species might reveal previously unrecognized adaptations for digging behavior. As these research approaches develop, our understanding of dinosaur behavioral adaptations to environmental stress will undoubtedly expand.

Conclusion: A Nuanced Picture of Dinosaur Survival Strategies

The evidence suggests that while complete underground living was not feasible for most dinosaur species, certain smaller dinosaurs did indeed utilize burrows and underground spaces as part of their survival strategies, particularly in regions with seasonal climate extremes. Rather than a simple yes or no answer, the question of underground dinosaur activity reveals a complex spectrum of behaviors adapted to specific environmental challenges and physiological constraints. This nuanced understanding enriches our appreciation of dinosaur adaptability and ecological roles. It also serves as a reminder that these remarkable animals possessed sophisticated behavioral repertoires that extended beyond the popular representations often depicted in media. As paleontologists continue investigating the traces of dinosaur behavior preserved in the fossil record, the full story of how these creatures responded to environmental challenges, including potential underground sheltering during climate shifts, will continue to unfold, deepening our understanding of Earth’s most magnificent prehistoric inhabitants.