While names like Mary Anning and Roy Chapman Andrews might ring familiar bells in the halls of paleontological fame, countless other dedicated scientists have worked tirelessly behind the scenes, revolutionizing our understanding of prehistoric life. These unsung heroes of paleontology have excavated crucial fossils, developed innovative methodologies, and challenged prevailing theories, yet they rarely receive proper recognition in popular culture. Their discoveries form the foundation of what we understand about dinosaurs today, from their appearance and behavior to their evolutionary relationships. Let’s unearth the stories of seven remarkable paleontologists whose contributions deserve far greater acknowledgment in the annals of scientific history.

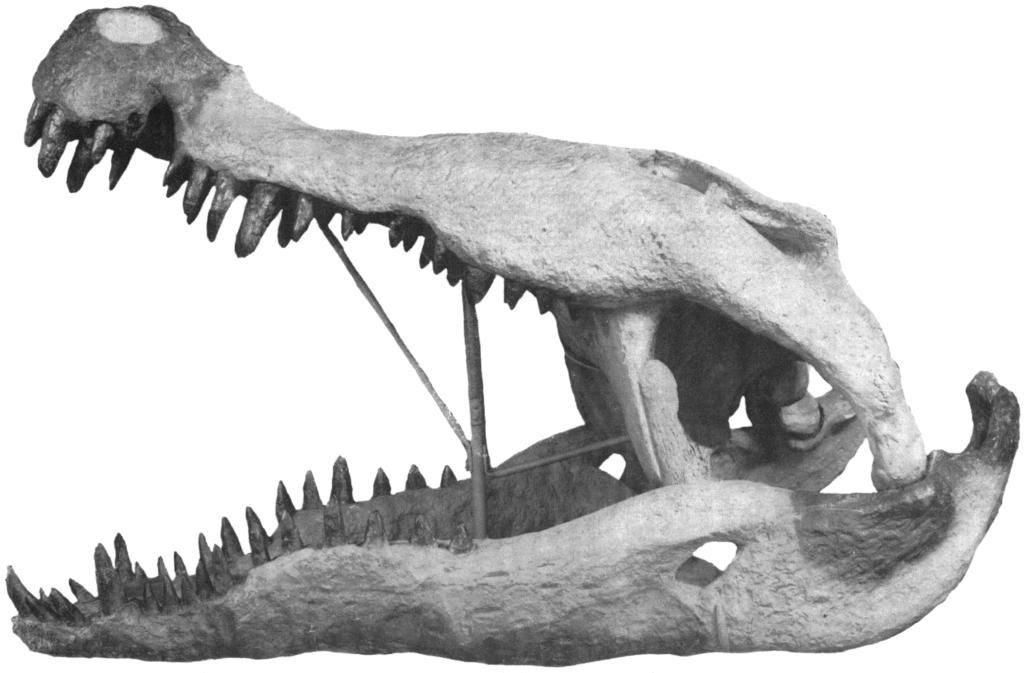

Barnum Brown: The First Fossil Hunter Who Found T. Rex

While paleontology enthusiasts might recognize Barnum Brown’s name, the general public remains largely unaware of the man who discovered the most iconic dinosaur of all time. Born in 1873 in Kansas, Brown spent over 60 years collecting for the American Museum of Natural History, becoming their most successful fossil hunter in history. His crowning achievement came in 1902 when he unearthed the first documented remains of Tyrannosaurus rex in Hell Creek, Montana, changing the face of paleontology and popular culture forever. Brown’s collecting techniques were revolutionary for his time, and he developed systematic approaches to excavation that are still used today. What makes his relative obscurity particularly surprising is that he discovered dozens of other important dinosaur species while often working in his signature formal attire—complete with a fedora—even in the harshest field conditions.

Franz Nopcsa: The Baron Who Pioneered Dinosaur Physiology

Baron Franz Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvás represents one of the most colorful and tragic figures in paleontological history, whose contributions remain criminally underappreciated. Born to Hungarian nobility in Transylvania in 1877, Nopcsa’s scientific journey began when his sister discovered dinosaur bones on the family estate. Despite no formal training, he became one of the first scientists to suggest that dinosaurs might have been warm-blooded. He displayed complex social behaviors—ideas considered radical at the time but largely accepted today. Nopcsa pioneered studies on dinosaur growth rates, sexual dimorphism, and island dwarfism long before these became mainstream research areas. His work on Romanian dinosaurs revealed the phenomenon of “insular dwarfism,” where species evolved smaller sizes on islands due to the limited resources available. Beyond paleontology, Nopcsa worked as a spy during World War I, attempted to become the king of Albania, and ultimately died by suicide in 1933 after losing his family fortune, leaving behind groundbreaking research that was decades ahead of its time.

Tilly Edinger: The Refugee Who Founded Paleoneurology

Johanna Gabrielle Ottilie “Tilly” Edinger created an entire scientific discipline that fundamentally changed how we understand dinosaur brains and behavior, yet remains virtually unknown outside specialist circles. Born to a prominent Jewish family in Germany in 1897, Edinger pioneered the field of paleoneurology—the study of fossil brains through endocasts (natural molds of brain cavities). Her 1929 book “Die fossilen Gehirne” (Fossil Brains) established this entirely new branch of paleontology. As the Nazi regime rose to power, Edinger, who was already deaf from a childhood illness, fled Germany in 1939 and eventually settled at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. Despite these immense personal challenges, she continued her groundbreaking work studying the evolution of brain structures across various prehistoric animals, including dinosaurs. Her research provided the first scientific understanding of dinosaur brain anatomy and intelligence, directly influencing how these creatures are portrayed in museums and popular media today. Edinger’s methodology and observations remain fundamental to modern paleontological research on dinosaur cognition and behavior.

Roland T. Bird: The High School Dropout Who Tracked Dinosaur Footprints

Roland T. Bird never received formal scientific training, yet his contributions to understanding dinosaur behavior through ichnology (the study of tracks and traces) remain unparalleled. After dropping out of high school, Bird became fascinated with fossils while working various jobs across America during the Great Depression. His life changed when he saw dinosaur footprints for sale in a New Mexico trading post and reported them to the American Museum of Natural History, leading to his hiring as a field collector. Bird’s most significant discovery came in the 1940s along the Paluxy River in Texas, where he documented extensive sauropod and theropod trackways that provided the first concrete evidence of herding behavior in dinosaurs. His meticulous excavation of these tracks, which included building dams to divert the river and developing new techniques for removing and preserving fragile impressions, set new standards for ichnological research. Bird’s observations challenged existing views about dinosaur behavior and locomotion, particularly the notion that sauropods were too heavy to walk on land and needed water to support their massive weight—a misconception that persisted until his revolutionary fieldwork.

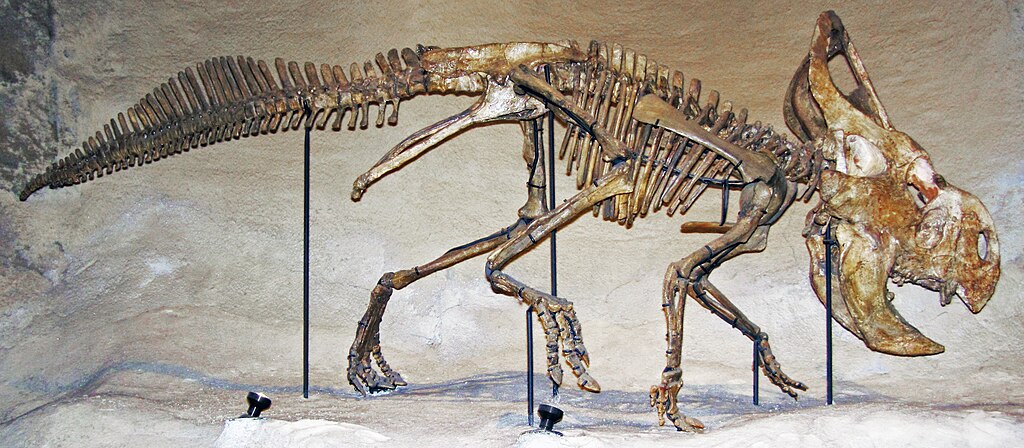

Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska: The Scientist Who Braved the Gobi Desert

The extraordinary career of Polish paleontologist Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska dramatically expanded our understanding of the Mesozoic world, yet her name remains unfamiliar to most dinosaur enthusiasts. Beginning in 1963, she led a series of groundbreaking Polish-Mongolian expeditions into the Gobi Desert that recovered some of the most important dinosaur and early mammal fossils ever found. Perhaps her most famous discovery was the fighting dinosaurs—a Velociraptor and Protoceratops preserved in combat, which provided unprecedented evidence of predator-prey interactions in the fossil record. Beyond dinosaurs, Kielan-Jaworowska revolutionized our understanding of Mesozoic mammals, demonstrating that they were far more diverse and complex than previously thought. Her research challenged the long-held belief that mammals during the dinosaur era were all small, primitive creatures, showing instead that they had already developed sophisticated adaptations and occupied various ecological niches. Working during the Cold War era and facing both political restrictions and harsh field conditions, her scientific achievements are all the more remarkable for the obstacles she overcame to advance paleontological knowledge.

Dong Zhiming: The Father of Chinese Dinosaur Paleontology

Few Western dinosaur enthusiasts recognize the name Dong Zhiming, despite his discovery and naming of more dinosaur species than almost any other paleontologist in history. Born in 1937 and surviving the tumultuous Cultural Revolution in China, Dong persisted in his scientific pursuits when paleontology was considered a “bourgeois” field. Beginning serious fieldwork in the 1970s, he went on to discover or name over 20 new dinosaur genera, including the massive Mamenchisaurus with its extraordinarily long neck and the bizarre theropod Monolophosaurus. Dong’s work was crucial in establishing China as one of the world’s most important regions for dinosaur discoveries, particularly for understanding the evolution of birds from theropod dinosaurs. His comprehensive 1992 book “Dinosaurian Faunas of China” became the definitive reference on Chinese dinosaurs, introducing many previously unknown Asian species to Western science. Beyond his direct discoveries, Dong trained generations of Chinese paleontologists who continue making groundbreaking finds today, creating a lasting scientific legacy that has fundamentally altered our global understanding of dinosaur evolution and diversity.

Elizabeth “Betsy” Nicholls: The Researcher Who Rescued Marine Reptiles from Obscurity

While technically focusing on marine reptiles rather than dinosaurs, Elizabeth “Betsy” Nicholls’ work dramatically expanded our understanding of the Mesozoic ecosystem in which dinosaurs lived, providing crucial context for their evolution and dominance. As curator of marine reptiles at the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta, Canada, Nicholls led the excavation of the largest marine reptile ever discovered—a 75-foot ichthyosaur from British Columbia that took five field seasons to collect. This monumental specimen, named Shonisaurus sikanniensis, revolutionized scientific understanding of marine reptile size and ecology during the age of dinosaurs. Nicholls specialized in studying ichthyosaurs, dolphin-like marine reptiles that evolved from land animals returning to the sea, documenting their evolutionary adaptations across millions of years. Her meticulous research on the transition between Early and Middle Triassic marine ecosystems helped explain how marine reptiles diversified after the devastating Permian-Triassic extinction event, providing important insights into the recovery patterns that allowed dinosaurs to eventually dominate terrestrial environments. Nicholls’ work demonstrated that understanding dinosaurs requires examining the entire Mesozoic ecosystem, not just the terrestrial components.

The Critical Role of Museum Preparators in Dinosaur Science

While not individual paleontologists, the collective contributions of fossil preparators represent one of the most underappreciated aspects of dinosaur paleontology, deserving recognition. These skilled technicians transform rough field specimens into scientifically valuable fossils through painstaking laboratory work that can take thousands of hours per specimen. Historically, preparators like Adam Hermann at the American Museum of Natural History created the first mounted dinosaur skeletons that captured public imagination, while receiving virtually no credit for their artistic and technical innovations. In modern times, preparators have developed techniques like acid preparation and CT scanning that reveal previously inaccessible anatomical details, fundamentally changing scientific understanding of dinosaur biology. Many groundbreaking dinosaur discoveries would remain encased in stone without these specialists’ work, as even the most significant fossil find requires expert preparation before scientific study can begin. Despite their crucial role, preparators rarely appear as authors on scientific papers or receive public recognition, representing a systematic oversight in how we acknowledge contributions to paleontological knowledge.

How Amateur Collectors Advanced Professional Paleontology

The boundary between amateur and professional has often blurred throughout paleontological history, with numerous important dinosaur discoveries made by dedicated fossil enthusiasts who lacked formal credentials. The teenage Marion Brandvold’s discovery of Maiasaura nests in Montana provided the first definitive evidence of parental care in dinosaurs, revolutionizing scientific understanding of dinosaur behavior. Similarly, fossil hunter Stan Sacrison’s discovery of “Sue,” the most complete T. rex ever found, fundamentally advanced research on this iconic predator despite his lack of academic credentials. These contributions highlight paleontology’s unique position as a science where non-professionals continue making substantive discoveries. Throughout the discipline’s history, self-taught fossil hunters have often possessed superior field skills and local geological knowledge compared to their academically trained counterparts. The collaboration between amateur collectors and professional researchers has proven particularly fruitful in regions like the American West, where vast fossil-bearing exposures cannot be systematically explored by limited academic personnel alone. This collaborative tradition continues today, with many important specimens initially identified by amateur collectors before making their way to research institutions.

The Lasting Impact of Soviet-Era Paleontology

Political isolation during the Cold War created a parallel universe of dinosaur research in the Soviet Union that remained largely unknown to Western scientists for decades. Soviet paleontologists conducted extensive expeditions throughout Central Asia, particularly Mongolia, recovering thousands of specimens that formed entirely different interpretations of dinosaur evolution than those developing in North America. The innovative work of scientists like Ivan Efremov, who developed taphonomy (the study of how organisms decay and become fossilized) in the 1940s, took decades to be recognized in Western paleontology despite its fundamental importance. Similarly, Anatoly Rozhdestvensky’s extensive research on hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) provided crucial insights into their diversity and evolutionary relationships that complemented North American findings. Soviet paleontologists often worked with limited resources and under difficult political conditions, yet produced exceptional scientific research that eventually transformed global understanding of dinosaur paleobiology when East-West scientific exchanges increased after the 1980s. The incorporation of this previously isolated research into the worldwide scientific community significantly expanded the dataset available for understanding dinosaur evolution and filled crucial geographical gaps in the fossil record.

How New Technologies Are Uncovering Hidden Contributors

Modern digital archives and research tools are finally bringing recognition to previously overlooked paleontologists, particularly women and scientists from non-Western countries whose contributions were systematically minimized in traditional historical accounts. The digitization of field notes, correspondence, and institutional records has revealed that many discoveries attributed to famous paleontologists relied heavily on unacknowledged collaborators and assistants. For example, recent archival research has highlighted Annie Alexander’s crucial role in funding and conducting University of California paleontological expeditions in the early 1900s, despite her name rarely appearing in scientific publications. Similarly, digital access to international journals has brought attention to pioneering work by Japanese paleontologist Tadahiro Kan, who made significant discoveries in China and Mongolia before World War II that were subsequently overlooked in Western scientific literature. Social media and online paleontology communities have also created platforms for recognizing contemporary contributors who might otherwise remain unknown outside specialized academic circles. This technological democratization of historical research is gradually producing a more accurate and inclusive understanding of who built our knowledge of dinosaurs, revealing paleontology’s history to be far more diverse and collaborative than previously acknowledged.

The Future of Recognition in Paleontology

The paleontological community has begun implementing structural changes to ensure future contributors receive appropriate recognition regardless of their background or institutional affiliation. Many journals now require detailed author contribution statements that specifically acknowledge the work of field crews, preparators, and technical specialists who traditionally remained invisible in scientific publications. Museums are increasingly highlighting the full teams behind major discoveries in their exhibits, rather than attributing finds solely to expedition leaders. Educational initiatives like the Bearded Lady Project have documented the significant but often unrecognized contributions of women in paleontology through photography and film, challenging stereotypical portrayals of who conducts fossil research. Digital paleontology platforms now provide opportunities for wider participation in the scientific process, allowing citizen scientists to contribute meaningfully to research through activities like transcribing field notes or tagging images in massive fossil databases. These changes reflect a growing recognition that paleontology’s future depends on acknowledging its full human diversity and creating more inclusive pathways for participation in scientific discovery.

The Quiet Architects of Dino Science

The extraordinary individuals highlighted in this article represent just a fraction of the overlooked contributors to our dinosaur knowledge. Their stories remind us that scientific progress rarely stems from lone geniuses but emerges through the collective efforts of diverse individuals working across generations and geographical boundaries. The next time you marvel at a museum’s towering dinosaur skeleton or enjoy the latest paleontological discovery in the news, remember that behind these wonders stands a long line of dedicated scientists, many whose names you’ll never know, who, piece by piece, assembled our understanding of Earth’s magnificent prehistoric past. By acknowledging these unsung heroes, we gain not only a more accurate history of paleontology but also a deeper appreciation for the collaborative nature of scientific discovery itself.