When dinosaurs roamed the Earth, North America was home to some of the most magnificent creatures that ever lived. Among them was Alamosaurus sanjuanensis, a colossal sauropod that holds the distinction of being one of the last dinosaurs to inhabit the continent before the mass extinction event 66 million years ago. This towering herbivore, with its long neck and whip-like tail, represents an important chapter in our understanding of dinosaur evolution and extinction. As we uncover more fossils and apply new technologies to studying this remarkable animal, we continue to gain insights into the final days of the dinosaur era in North America.

Discovery and Naming: Unearthing a Giant

Alamosaurus was first discovered in 1922 by Charles Whitney Gilmore, a paleontologist working in the Ojo Alamo Formation of New Mexico. The genus name “Alamosaurus” refers to the Ojo Alamo sandstone where the initial specimens were found, rather than the Alamo in Texas or the famous battle site, as is sometimes mistakenly believed. The species name “sanjuanensis” acknowledges San Juan County, New Mexico, where these first fossils were unearthed. Interestingly, the initial discovery consisted only of a shoulder blade, some vertebrae, and a partial pelvis—a modest beginning for what would later be recognized as one of North America’s largest dinosaurs. Despite being discovered a century ago, new Alamosaurus material continues to be found, gradually filling in our understanding of this magnificent creature.

Physical Characteristics: A True Titan

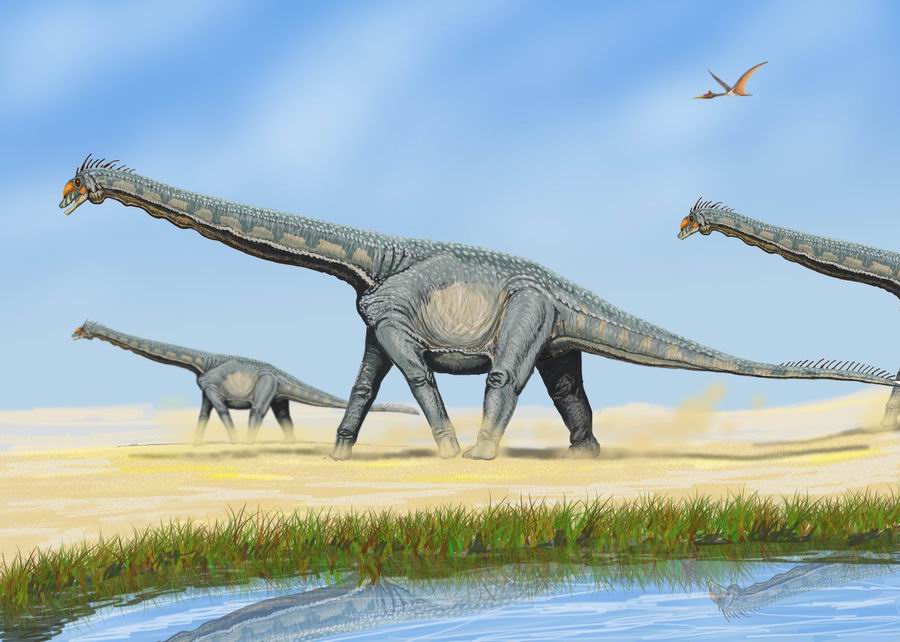

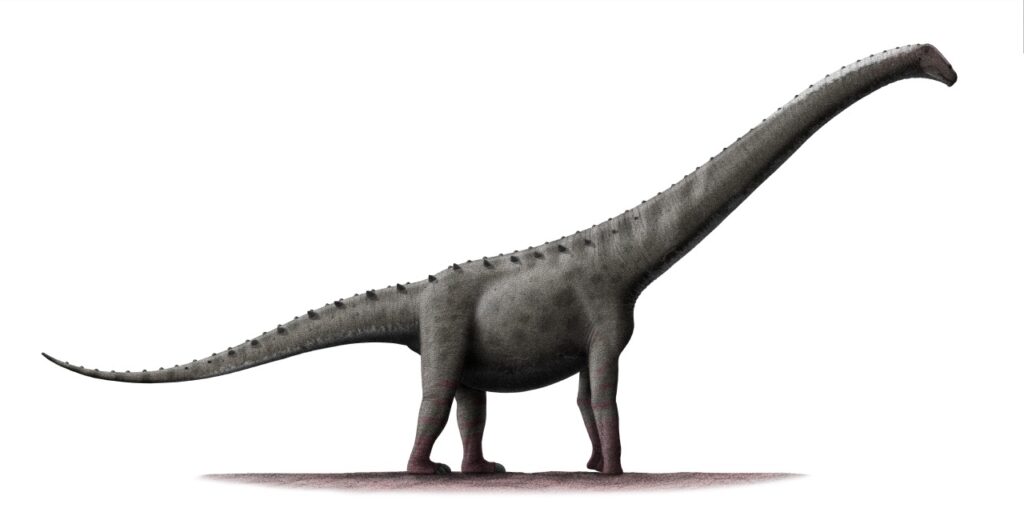

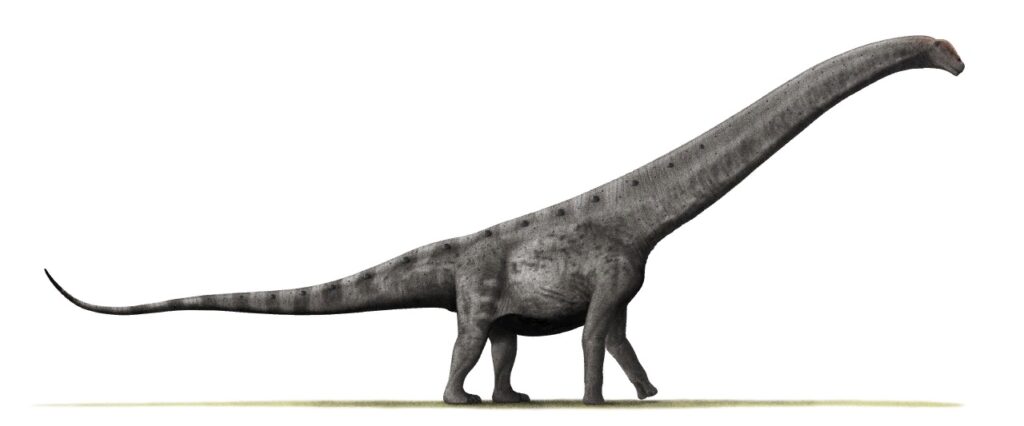

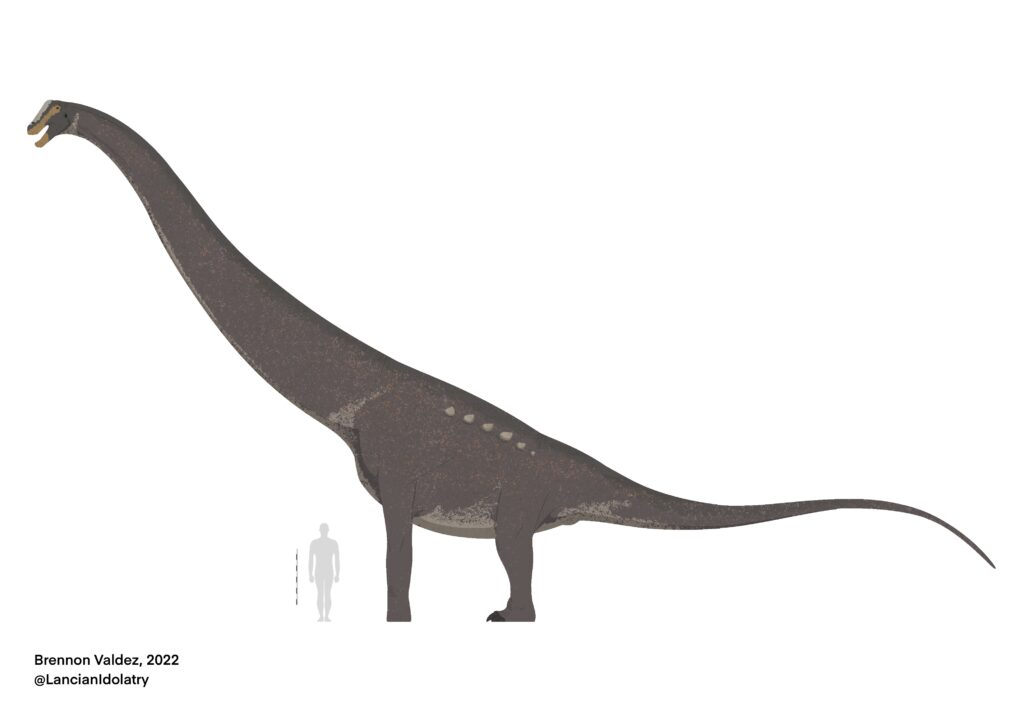

Alamosaurus was a titanosaur, belonging to a group of sauropods that dominated the Southern Hemisphere during the Late Cretaceous period. It had the classic sauropod body plan: a small head perched atop an extraordinarily long neck, a robust barrel-shaped body, thick columnar legs, and an elongated whip-like tail. Conservative estimates suggest adult Alamosaurus individuals reached lengths of 69-72 feet (21-22 meters) and may have weighed between 30-40 tons. Some researchers believe that particularly large specimens could have been even more massive, potentially reaching lengths of up to 98 feet (30 meters) and weighing as much as 80 tons. Unlike some of its titanosaur relatives, Alamosaurus appears to have lacked the bony armor plates (osteoderms) embedded in its skin that characterized many other titanosaurs.

Evolutionary History: A Southern Immigrant

One of the most fascinating aspects of Alamosaurus is its evolutionary relationship to other dinosaurs. Phylogenetic analyses consistently show that Alamosaurus was more closely related to South American titanosaurs than to earlier North American sauropods. This suggests that Alamosaurus or its immediate ancestors likely migrated from South America into North America during the Late Cretaceous period. This migration would have occurred when the two continents were connected by land bridges that periodically formed as sea levels fluctuated. The arrival of Alamosaurus in North America represents an important biogeographical event, as sauropods had been largely absent from the continent for several million years before its appearance. This “reconquista” of North America by titanosaurs offers important insights into dinosaur dispersal patterns and the dynamics of prehistoric ecosystems.

Habitat and Range: The Final Frontier

Alamosaurus fossils have been discovered primarily in the southwestern United States, with significant finds in New Mexico, Texas, and Utah. The environments these areas represented during the Late Cretaceous period (approximately 70-66 million years ago) were quite different from the arid landscapes we see today. Paleoenvironmental evidence suggests Alamosaurus inhabited subtropical coastal plains and river systems, environments rich in vegetation that could support the enormous appetites of these giants. The distribution of fossils indicates these dinosaurs may have preferred inland habitats slightly removed from the Western Interior Seaway, the large inland sea that divided North America during this time. Climate modeling of the Late Cretaceous suggests these regions would have experienced seasonal rainfall patterns with distinct wet and dry seasons, creating challenging conditions that Alamosaurus was well-adapted to navigate.

Diet and Feeding Habits: Consuming Mountains of Vegetation

As a titanosaur, Alamosaurus was an obligate herbivore with a voracious appetite necessary to sustain its enormous body. Its dental morphology consisted of pencil-shaped teeth well-suited for stripping foliage rather than chewing, indicating that, like other sauropods, it swallowed vegetation whole to be processed in its massive digestive system. Alamosaurus likely fed on a variety of plant materials available in its environment, including conifers, cycads, ferns, and early flowering plants that were becoming increasingly prevalent in the Late Cretaceous. Based on the height of a fully extended neck, adult Alamosaurus could have browsed vegetation at heights of up to 40 feet (12 meters), accessing food sources beyond the reach of most contemporary herbivores. The massive daily food intake of an adult Alamosaurus has been estimated at several hundred pounds of plant material, suggesting these animals would have significantly shaped the plant communities in their environments.

Growth and Development: From Egg to Giant

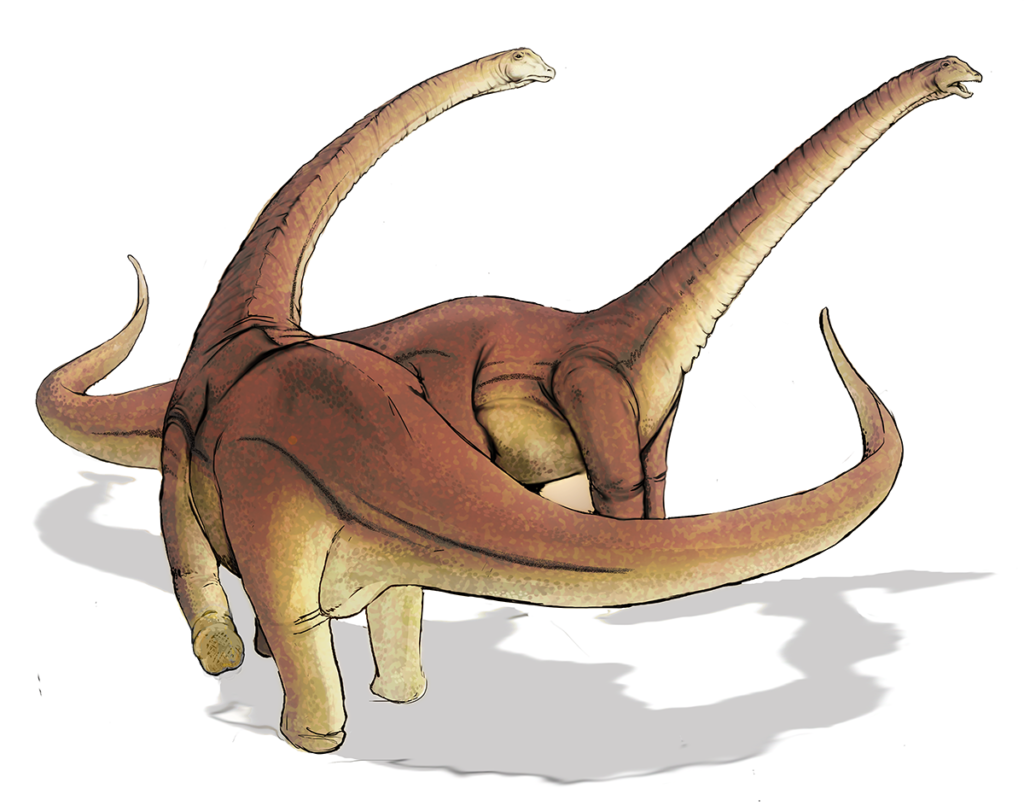

The life cycle of Alamosaurus, from hatching to reaching full adult size, represents one of the most dramatic growth trajectories in the animal kingdom. Though no definitive Alamosaurus eggs have been identified, related titanosaurs laid spherical eggs roughly 6-8 inches (15-20 cm) in diameter, often in large communal nesting grounds. Histological studies of Alamosaurus bones show growth rings similar to those seen in trees, indicating rapid growth during early life that gradually slowed as the animals approached maturity. Scientists estimate that Alamosaurus may have reached sexual maturity before attaining full size, perhaps at around 20-30 years of age. Based on comparisons with better-studied titanosaurs, Alamosaurus likely had a life span of 70-100 years, making these animals not only among the largest but also among the longest-lived creatures of their time.

Contemporaries: Sharing the Landscape with T. rex

Alamosaurus shared its Late Cretaceous habitats with some of the most iconic dinosaurs known to science, most notably Tyrannosaurus rex. This creates the tantalizing scenario of North America’s largest predator potentially hunting its largest herbivore. Other notable contemporaries included ceratopsians like Triceratops, hadrosaurs such as Edmontosaurus, and smaller theropods like Dromaeosaurus. Paleontologists have debated whether adult Alamosaurus would have been vulnerable to predation by even the largest Tyrannosaurus individuals, with most concluding that only juvenile or weakened Alamosaurus would have been practical prey targets. The ecosystem Alamosaurus inhabited was rich and complex, with numerous herbivores utilizing different feeding strategies to partition resources, and a hierarchy of predators maintaining population balances. Fossil evidence suggests that Alamosaurus was relatively common in its environment, indicating it was a successful and well-adapted species despite the challenging and changing conditions of the terminal Cretaceous.

Defensive Adaptations: Size as a Shield

Unlike many dinosaurs that evolved horns, armor, or offensive weapons to deter predators, Alamosaurus relied primarily on its enormous size as its main defensive strategy. At 30-80 tons, an adult Alamosaurus would have been simply too massive for even the largest Tyrannosaurus to tackle safely. Beyond sheer size, Alamosaurus possessed a powerful whip-like tail that could potentially deliver devastating blows to would-be attackers. Computer modeling suggests the tip of such tails could reach supersonic speeds, creating a distinctive cracking sound similar to a bullwhip while delivering significant force. Social behavior may have provided additional protection, with some paleontologists suggesting Alamosaurus might have traveled in loose herds, particularly during breeding seasons or migrations. Young Alamosaurus, being more vulnerable to predation, may have benefited from protection within these groups until they reached sizes that deterred predators.

Locomotion and Posture: How Giants Moved

Moving a body as massive as that of Alamosaurus presented significant biomechanical challenges that shaped the animal’s anatomy and behavior. Like other titanosaurs, Alamosaurus had columnar limbs with reduced flexibility, providing the structural support necessary to bear its tremendous weight. Trackway evidence from related sauropods suggests these animals moved with slow, deliberate strides at walking speeds of perhaps 3-5 miles per hour. The wide-gauge stance characteristic of titanosaurs, with limbs positioned more laterally than those of earlier sauropods, provided greater stability at the cost of reducing maximum speed. Reconstructions of Alamosaurus vertebrae indicate a relatively straight neck posture rather than the swooping, swan-like curve often depicted in older illustrations. This straight-neck posture would have been more energy-efficient and biomechanically sound for supporting the weight of the head and neck, though it would limit vertical reaching ability somewhat compared to more flexible-necked sauropods.

Remarkable Fossil Discoveries: Big Bones Tell Tales

While initially known from fragmentary remains, subsequent Alamosaurus discoveries have yielded increasingly complete specimens that have dramatically improved our understanding of this dinosaur. A particularly significant find occurred in the Big Bend region of Texas in the 1990s, where paleontologists uncovered a partial skeleton including multiple vertebrae, ribs, and limb bones from an exceptionally large individual. In 2002, another important discovery in New Mexico produced a nearly complete sacrum (the vertebrae that connect to the pelvis) and hip bones that helped clarify the dimensions of adult Alamosaurus. Perhaps most exciting was the 2010-2012 excavation of juvenile Alamosaurus remains from the North Horn Formation of Utah, providing unprecedented insights into the growth patterns of these animals. The scarcity of skull material remains a significant limitation in Alamosaurus research, with cranial features largely inferred from related titanosaurs rather than from direct evidence.

Extinction Context: Last Days of the Dinosaurs

Alamosaurus holds particular scientific significance as one of the last non-avian dinosaurs to exist before the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event that wiped out approximately 75% of all species on Earth 66 million years ago. Fossils of Alamosaurus have been found in rock layers dating to within a million years of this catastrophic event, suggesting these enormous herbivores were present right up until the end of the Cretaceous. The extinction of Alamosaurus coincided with the impact of a massive asteroid or comet at what is now the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, an event that triggered global climate disruption. The disappearance of such a successful and specialized lineage highlights the indiscriminate nature of this extinction event, which affected even well-adapted species. Interestingly, some of Alamosaurus’ titanosaur relatives in South America seem to have been similarly successful right up to the extinction boundary, suggesting these animals were thriving rather than declining when disaster struck.

Cultural Impact and Popular Representation

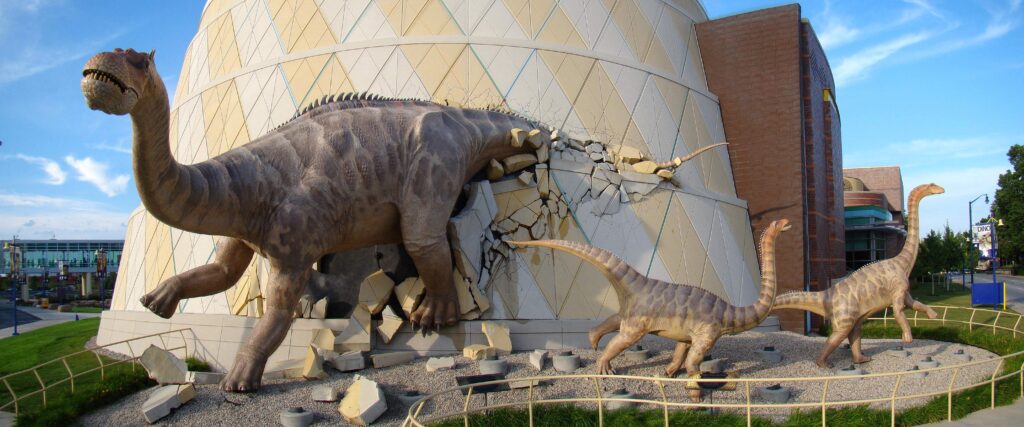

Despite being one of the largest and last dinosaurs in North America, Alamosaurus has received relatively little attention in popular culture compared to more famous dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex or Triceratops. The dinosaur has been featured in several museum exhibitions, most notably at the Perot Museum of Nature and Science in Dallas and the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science in Albuquerque, where impressive reconstructions help visitors appreciate the animal’s enormous scale. In scientific literature, Alamosaurus has become increasingly important as a representative of Late Cretaceous faunal exchange between North and South America. The dinosaur appears in various educational books and has been featured in some dinosaur documentaries, though rarely as the central focus. Paleontologists continue to advocate for greater recognition of Alamosaurus as an important part of North America’s prehistoric heritage and as a scientific window into the final chapter of non-avian dinosaur evolution on the continent.

Research Frontiers: What We’re Still Learning

Active research on Alamosaurus continues to yield new insights about this remarkable dinosaur. Recent technological approaches include CT scanning of fossils to examine internal structures, finite element analysis to understand biomechanical constraints, and improved phylogenetic methods to clarify evolutionary relationships. One current research direction involves isotope analysis of Alamosaurus teeth and bones to determine diet composition and migration patterns. Paleontologists are also investigating whether Alamosaurus, like some other titanosaurs, may have engaged in behaviors such as osteophagy (bone-eating) to obtain sufficient calcium for their massive skeletons. Questions about reproductive behavior remain largely unanswered, with ongoing debates about whether Alamosaurus attended to their nests and provided parental care like some modern reptiles. The scarcity of very young juvenile specimens represents a significant gap in our understanding of this animal’s life history, making the discovery of nursery sites a particularly important goal for future fieldwork.

Living Legacy: What Alamosaurus Teaches Us

The study of Alamosaurus offers valuable scientific lessons that extend far beyond dinosaur enthusiasts. As one of the largest land animals ever to walk North America, Alamosaurus provides insights into the upper limits of terrestrial body size and the adaptations necessary to support such massive proportions. The animal’s apparent success just before the mass extinction event challenges simplistic narratives about dinosaurs being in decline before the asteroid impact. From an ecological perspective, Alamosaurus demonstrates how large herbivores can function as ecosystem engineers, shaping plant communities and creating habitat modifications that benefit smaller organisms. The biogeographical story of Alamosaurus, with its South American origins, reminds us that continental connections and species migrations have profoundly influenced biodiversity patterns throughout Earth’s history. Perhaps most poignantly, Alamosaurus represents the culmination of 165 million years of sauropod evolution—a lineage that produced the largest land animals in Earth’s history before disappearing completely in a geological instant.

Conclusion

As paleontologists continue to uncover new Alamosaurus fossils and apply cutting-edge analytical techniques to existing specimens, our understanding of this magnificent dinosaur continues to evolve. What remains clear is that Alamosaurus represents an extraordinary final chapter in the story of North American dinosaurs—a testament to the remarkable adaptability and success of the dinosaur lineage right up until its sudden end. In the ancient environments of what would become the American Southwest, these gentle giants left their mark on the landscape and in the fossil record, providing us with an enduring window into a lost world where titans walked the Earth.