Deep in the heart of Argentine Patagonia, where the wind never stops howling and the landscape stretches endlessly like a forgotten canvas, lies one of the world’s most remarkable windows into prehistoric life. The Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio in Trelew doesn’t just house dinosaur bones – it guards the secrets of giants that once thundered across these very plains millions of years ago. This isn’t your typical museum experience where you shuffle past glass cases and read placards. Here, you’re standing face-to-face with creatures so massive they’d make a blue whale look like a goldfish, in the very region where their fossilized remains emerged from ancient rock formations.

The Birthplace of Patagonian Paleontology

Trelew might seem like an unlikely place for one of South America’s most important paleontological museums, but this Welsh-settled town in Chubut Province sits at the epicenter of what scientists call a “dinosaur goldmine.” The Feruglio Museum, named after Italian geologist Egidio Feruglio who first mapped Patagonia’s geological treasures in the 1920s, opened its doors in 1990 with a mission that seemed almost impossible: to showcase the incredible diversity of life that once flourished in this now-barren landscape.

What makes this location so special isn’t just the museum itself, but the surrounding badlands where paleontologists continue to unearth new species almost every field season. The Chubut River valley has yielded more complete dinosaur skeletons than almost anywhere else on Earth, with rock formations dating back over 100 million years. When you walk through Trelew’s quiet streets today, you’re literally walking above one of the richest fossil beds ever discovered.

Argentinosaurus: The Titan That Redefined Gigantism

Standing before the reconstructed skeleton of Argentinosaurus huinculensis in the Feruglio Museum is like meeting your worst nightmare and greatest dream simultaneously. This creature, discovered in nearby Neuquén Province in 1987, weighs in at an estimated 70 tons and stretches over 100 feet from nose to tail – longer than three school buses lined up end to end. The sheer scale becomes overwhelming when you realize that this gentle giant munched on ferns and conifers all day, every day, consuming up to 880 pounds of vegetation daily just to fuel its massive frame.

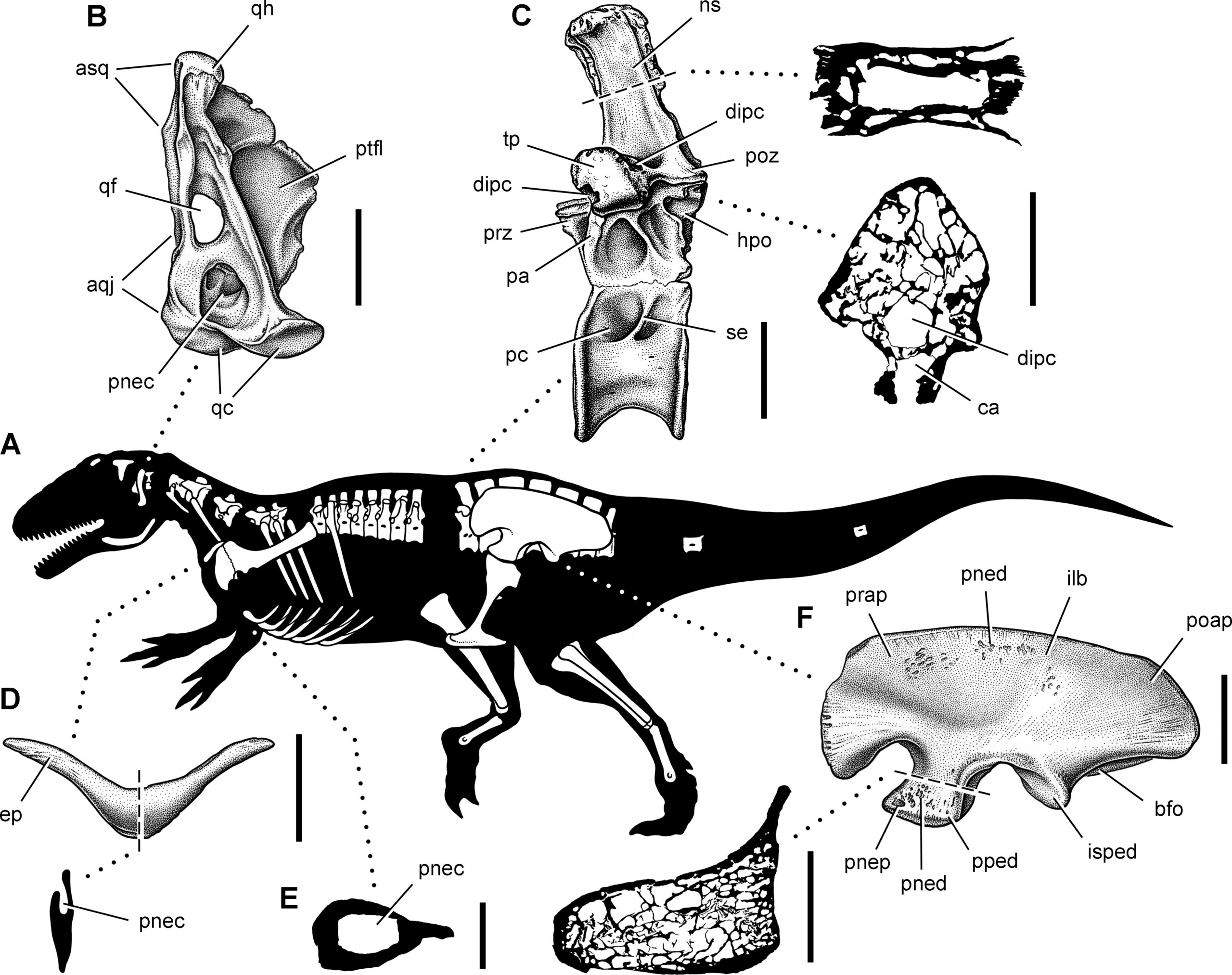

What’s truly mind-boggling about Argentinosaurus isn’t just its size, but how it managed to support such incredible weight on four legs. The museum’s interactive displays show how its backbone contained hollow chambers, similar to bird bones, that reduced weight without sacrificing strength. Scientists estimate that when this titan walked, each footstep would have registered on primitive seismographs from miles away.

Giganotosaurus: The Predator That Ruled Before T-Rex

If Argentinosaurus was the gentle giant of Patagonia, then Giganotosaurus carolinii was its absolute nightmare. This apex predator, first discovered in 1993 just a few hours’ drive from Trelew, makes Tyrannosaurus rex look like a house cat in comparison. At 43 feet long and weighing up to 8 tons, Giganotosaurus possessed a skull longer than a bathtub and serrated teeth designed for slicing through thick hide and bone.

The museum’s Giganotosaurus exhibit doesn’t just display static bones – it brings this monster to life through cutting-edge technology that shows how it hunted. Unlike the bone-crushing bite of T-rex, Giganotosaurus used a slashing technique, inflicting deep wounds that would cause massive blood loss in prey. The interactive display lets visitors experience the difference between these hunting strategies, and it’s genuinely terrifying to imagine being chased by either predator.

The Carnotaurus Revolution: Argentina’s Horned Devil

Perhaps no dinosaur discovery has captured imaginations quite like Carnotaurus sastrei, the “meat-eating bull” that stalked Patagonian plains 72 million years ago. Found in 1984 in the Chubut Province, this bizarre predator sported two devil-like horns above its eyes and arms so reduced they made T-rex’s look muscular. The Feruglio Museum’s Carnotaurus display reveals something that paleontologists are still trying to understand: how did a predator with virtually useless arms become such an effective hunter?

The answer lies in pure speed and specialized hunting tactics. Carnotaurus could reach speeds of up to 35 mph, making it one of the fastest large predators that ever lived. Its lightweight build and powerful legs turned it into a prehistoric cheetah, capable of running down prey across the open plains. The museum’s motion-capture technology shows visitors exactly how this horned devil moved, and it’s both beautiful and terrifying to watch.

Dreadnoughtus: When Bigger Actually Meant Better

The Feruglio Museum’s crown jewel might be its Dreadnoughtus schrani exhibit, showcasing one of the most complete super-massive dinosaur skeletons ever found. Named after the early 20th-century battleships that “feared nothing,” this 85-foot-long titan weighed approximately 65 tons and represents the absolute pinnacle of dinosaur gigantism. What makes Dreadnoughtus special isn’t just its size, but the fact that scientists have recovered over 70% of its skeleton, giving us unprecedented insight into how these giants actually lived.

The museum’s detailed biomechanical analysis reveals that Dreadnoughtus was still growing when it died, meaning it could have become even larger. This discovery fundamentally changed how paleontologists think about dinosaur growth patterns and maximum body size. Standing next to this gentle giant’s reconstructed skeleton, visitors often report feeling emotionally overwhelmed – it’s impossible to comprehend that such creatures once walked the Earth.

The Mysterious World of Patagonian Sauropods

Beyond the famous giants, the Feruglio Museum showcases dozens of lesser-known but equally fascinating sauropods that called Patagonia home. Species like Puertasaurus reuili and Futalognkosaurus dukei demonstrate that South America was essentially a sauropod paradise during the Late Cretaceous period. These creatures evolved in isolation after the supercontinent Gondwana began breaking apart, leading to unique adaptations found nowhere else on Earth.

The museum’s comparative anatomy section reveals how different sauropod species occupied different ecological niches – some were low browsers, others reached high into ancient canopies, and still others specialized in aquatic plants. This diversity challenges the old stereotype of dinosaurs as simple, primitive creatures. Instead, they were sophisticated animals with complex behaviors and specialized feeding strategies that allowed multiple giant species to coexist in the same environment.

Predator-Prey Dynamics in Ancient Patagonia

One of the most compelling aspects of the Feruglio Museum’s exhibits is how they illustrate the complex predator-prey relationships that existed in Cretaceous Patagonia. The famous “dueling dinosaurs” display shows evidence of actual combat between predators and their massive prey, including bite marks on sauropod bones that match the teeth of contemporary carnivores. These interactions weren’t just theoretical – they were daily life-and-death struggles that shaped the evolution of both hunters and hunted.

The museum’s ecosystem dioramas reveal that even the largest sauropods weren’t safe from predation. Pack-hunting abelisaurids like Mapusaurus roseae could potentially take down even adult titanosaurs through coordinated attacks. This dynamic created an evolutionary arms race where prey animals grew larger and more heavily armored, while predators became faster and more deadly. The evidence for this ancient warfare is written in the bones themselves.

Revolutionary Fossilization Techniques in Patagonian Badlands

What makes the Feruglio Museum’s collection so exceptional isn’t just what was found, but how it was preserved. The unique geological conditions of Patagonia created nearly perfect fossilization environments, with rapid burial in fine sediments that captured incredible detail. Some specimens retain impressions of skin texture, while others show evidence of internal organs and even stomach contents.

The museum’s laboratory viewing area lets visitors watch paleontologists preparing new specimens using techniques that would have been impossible just decades ago. CT scanning reveals internal bone structure without damaging fossils, while chemical analysis of preserved organic compounds provides insights into dinosaur metabolism and diet. These advances mean that every fossil tells a more complete story than ever before.

The Egg Mountain Discovery: Nesting Behaviors of Giants

Perhaps the most emotionally moving exhibit in the Feruglio Museum is the titanosaur nesting site discovered in nearby Auca Mahuevo. This extraordinary find revealed not just fossilized eggs, but evidence of sophisticated nesting behaviors among the largest animals that ever lived. The discovery of embryonic skin impressions inside some eggs provided the first direct evidence of what baby sauropods looked like, and the results were surprisingly delicate and bird-like.

The nesting site evidence suggests that these giants returned to the same areas year after year to lay their eggs, creating enormous rookeries that may have contained thousands of nests. Parent dinosaurs apparently covered their eggs with vegetation, much like modern crocodiles, creating warm, humid incubation environments. This level of parental care among creatures weighing dozens of tons challenges every assumption about dinosaur intelligence and social behavior.

Advanced Imaging Technology Reveals Hidden Secrets

The Feruglio Museum leads the world in applying cutting-edge technology to paleontological research. Their CT scanning facility has revealed internal structures in dinosaur bones that were previously invisible, including evidence of air sacs similar to those found in modern birds. This discovery revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur respiration and metabolism, showing that these giants were far more efficient than previously imagined.

Laser scanning technology allows researchers to create perfect digital models of fossils, enabling detailed analysis without risking damage to irreplaceable specimens. The museum’s virtual reality experiences let visitors walk alongside these ancient giants, experiencing their size and movement in ways that static displays simply cannot convey. These technological advances mean that each visit to the museum offers new discoveries and perspectives.

Climate Change and Dinosaur Evolution in Patagonia

The Feruglio Museum’s climate exhibits reveal how dramatically different Patagonia was during the age of dinosaurs. Instead of today’s cold, windswept plains, the region enjoyed a warm, humid climate with lush forests and extensive river systems. This tropical paradise supported the massive plant growth necessary to feed dozen of giant herbivores, creating one of the most productive ecosystems in Earth’s history.

As global temperatures began cooling toward the end of the Cretaceous period, the museum’s exhibits show how dinosaur communities responded to environmental pressure. Some species migrated to more favorable climates, others adapted to new food sources, and many simply went extinct. This ancient climate story offers sobering parallels to modern environmental challenges and demonstrates how even the most successful species can be vulnerable to rapid change.

The Ongoing Excavation Projects

What makes the Feruglio Museum truly special is that it’s not just displaying old discoveries – it’s actively involved in finding new ones. The museum sponsors multiple excavation projects throughout Patagonia, with new species being discovered and described on a regular basis. Recent finds include a new species of giant carnivore and several previously unknown titanosaur species, each adding pieces to our understanding of this ancient ecosystem.

The museum’s field work program allows visitors to participate in actual excavations, providing hands-on experience with paleontological techniques. These programs have led to significant discoveries by amateur paleontologists, proving that important scientific work doesn’t require advanced degrees. The thrill of uncovering a fossil that hasn’t seen daylight for 100 million years is something that changes people’s relationship with natural history forever.

Conservation and Future Research

The Feruglio Museum faces the ongoing challenge of preserving irreplaceable fossils while making them accessible to researchers and the public. Their conservation laboratory uses state-of-the-art techniques to stabilize fragile specimens, often working with materials that are millions of years old but as delicate as tissue paper. This work ensures that future generations will be able to study these incredible creatures.

Looking toward the future, the museum’s research programs focus on understanding dinosaur behavior, social structures, and ecological relationships. New analytical techniques promise to reveal even more secrets locked within ancient bones, potentially answering questions about dinosaur intelligence, communication, and family structures. Each new discovery adds another piece to the puzzle of how these magnificent creatures lived and thrived in ancient Patagonia.

A Living Laboratory of Ancient Life

The Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio represents more than just a collection of old bones – it’s a living laboratory where the ancient past comes alive through scientific research and public education. The giants of Patagonia tell a story of life’s incredible diversity and resilience, showing us that our planet has supported creatures beyond our wildest imagination. These dinosaurs ruled the Earth for over 160 million years, making our own species’ brief existence seem like a fleeting moment in comparison.

As climate change and habitat destruction threaten modern ecosystems, the lessons from Patagonia’s ancient giants become increasingly relevant. Their story reminds us that even the most successful species can face extinction when environmental conditions change too rapidly. The Feruglio Museum stands as both a testament to life’s incredible potential and a warning about our responsibility to protect the natural world that remains.

Walking through the museum’s halls, surrounded by the bones of creatures that dominated the Earth for millions of years, leaves visitors with a profound sense of wonder and humility. What secrets might still be buried in Patagonia’s badlands, waiting for the next generation of paleontologists to uncover?