The Iziko South African Museum stands as a testament to South Africa’s rich natural history, showcasing an impressive collection of ancient creatures that once roamed the Cape Town region and beyond. Located at the heart of Cape Town’s Company Gardens, this venerable institution has been enlightening visitors about South Africa’s prehistoric past since 1825, making it the country’s oldest museum. Its extensive paleontological exhibits transport visitors through time, from the earliest forms of life to the more recent prehistoric mammals that shaped the region’s unique biodiversity. The museum’s commitment to scientific accuracy, educational outreach, and cultural significance makes it an essential destination for anyone seeking to understand the complex tapestry of life that has evolved in this southernmost part of Africa over millions of years.

The Origins of Iziko South African Museum

The Iziko South African Museum’s journey began nearly two centuries ago, established in 1825 when Lord Charles Somerset, the then British governor of the Cape Colony, recognized the need for a repository of natural history specimens. Initially housed in a small building on the Parade, the museum started with a modest collection of zoological specimens and cultural artifacts gathered by explorers and scientists. As its collections expanded, the museum moved to its current neo-classical building in 1897, designed by architects Hubner and McKinley to properly showcase South Africa’s growing scientific treasures. The name “Iziko,” adopted in 1999, comes from the isiXhosa word meaning “hearth,” symbolizing the museum’s role as a cultural gathering place where knowledge is shared across generations. Throughout its existence, the museum has evolved from a colonial institution to a democratic one that seeks to represent all South Africans while maintaining its scientific rigor.

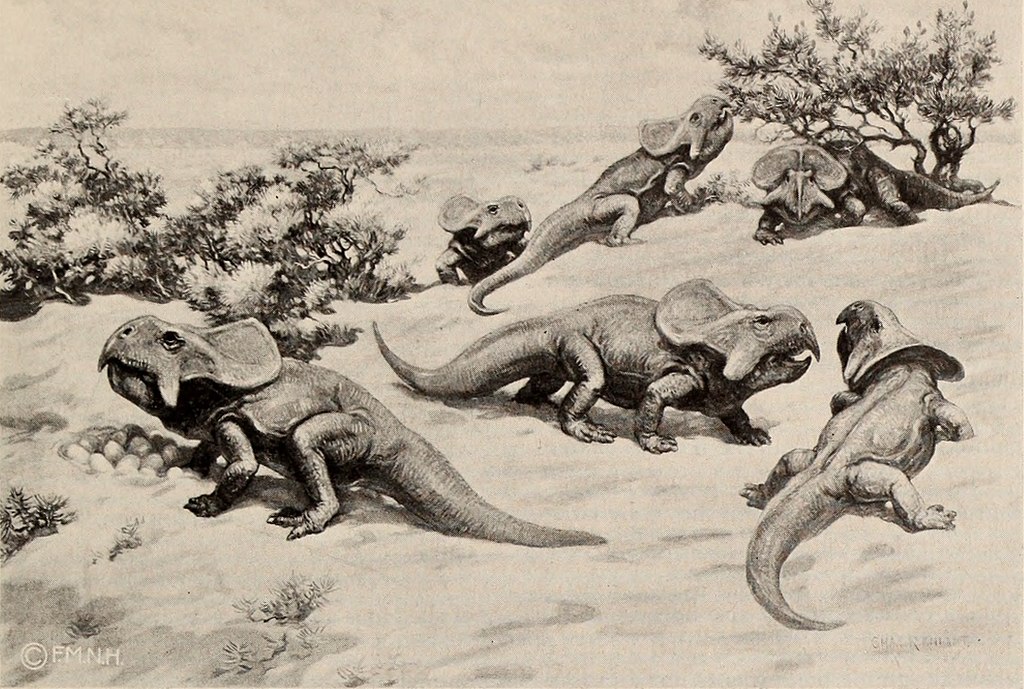

The Boonstra Dioramas: Windows to the Prehistoric Karoo

Among the museum’s most celebrated exhibitions are the Boonstra Dioramas, named after renowned paleontologist Lieuwe Dirk Boonstra, who dedicated his career to uncovering the ancient creatures of the Karoo Basin. These meticulously crafted three-dimensional scenes recreate the Permian landscape of approximately 250-260 million years ago, depicting therapsids—mammal-like reptiles that preceded dinosaurs—in their natural habitats. Visitors can marvel at the predatory Gorgonopsians with their saber-like canines, the herbivorous Pareiasaurus with its heavily armored body, and the Diictodon, a small burrowing therapsid that survived in vast numbers. Each diorama combines scientific accuracy with artistic vision, based on fossil evidence collected during decades of fieldwork in the Karoo region. The attention to detail extends to the recreated ancient vegetation and geological features, providing a comprehensive glimpse into a world that existed long before humans walked the Earth.

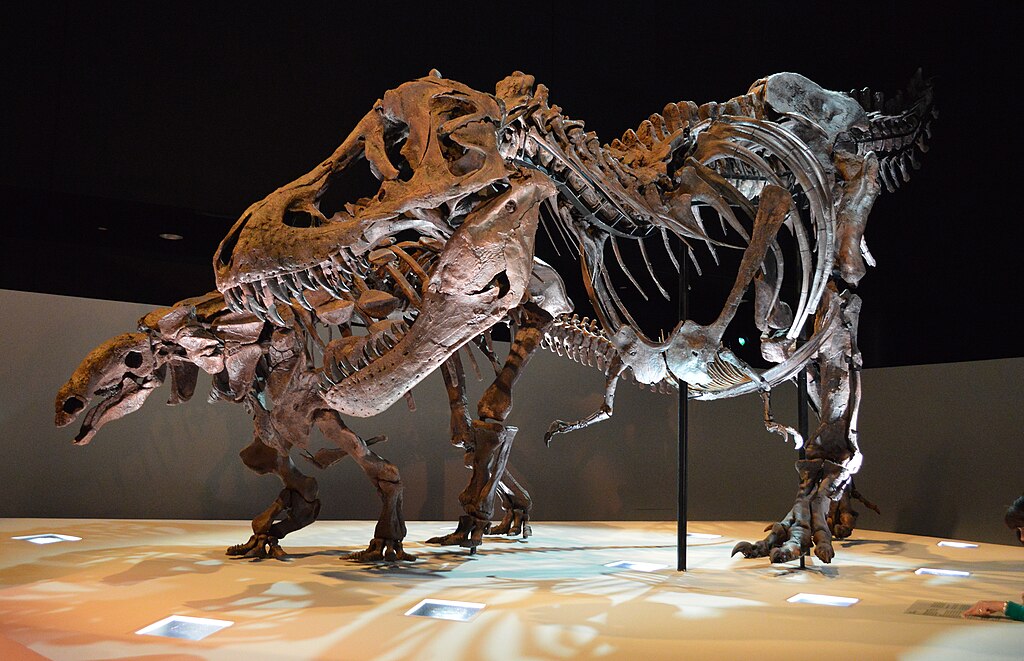

Dinosaurs of the Cape: The Mesozoic Gallery

The Mesozoic Gallery at Iziko takes visitors on a journey through the Age of Dinosaurs, showcasing the remarkable prehistoric creatures that once inhabited the Cape region during the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous periods. The centerpiece of this exhibition is the Massospondylus skeleton, a long-necked prosauropod dinosaur from the Early Jurassic period (approximately 200 million years ago) whose fossils were found in abundance throughout the Cape and neighboring regions. Visitors can also examine the fossils of Heterodontosaurus tucki, a small, nimble dinosaur with specialized teeth that suggest a varied diet, discovered in the Eastern Cape. The gallery presents not just the fossils themselves but contextualizes them within the changing landscapes and climates of Mesozoic southern Africa, explaining how these animals evolved and adapted over millions of years. Interactive displays demonstrate how paleontologists piece together evidence from fossilized bones, footprints, and eggs to understand dinosaur behavior, growth, and ecological relationships.

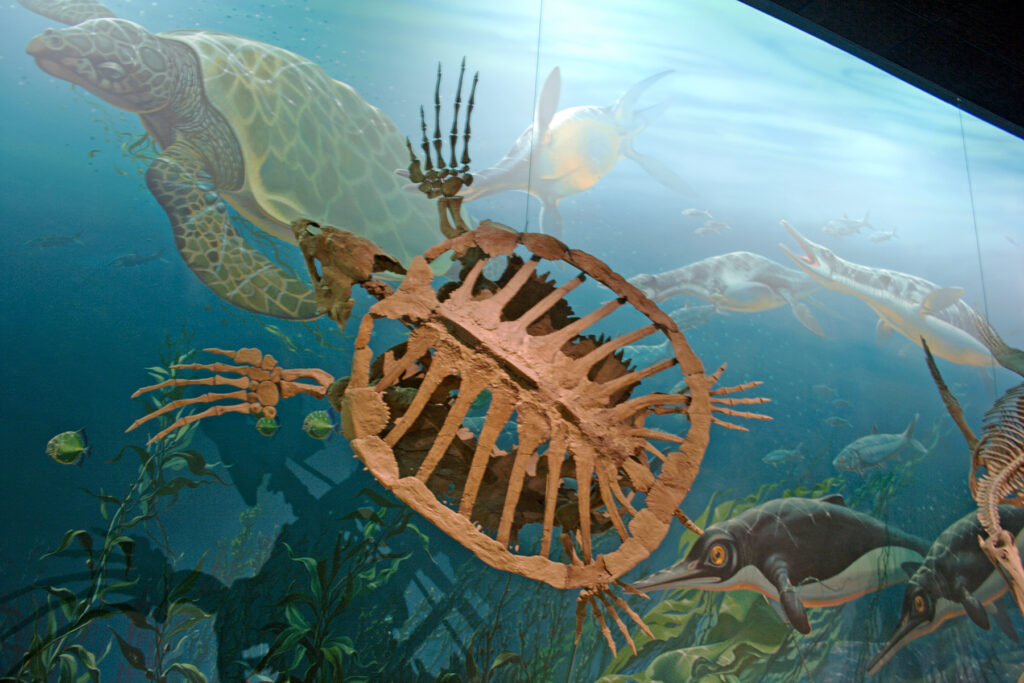

Marine Giants: Prehistoric Ocean Life

The marine paleontology section of the museum showcases the diverse and often massive creatures that swam in the ancient oceans surrounding what is now Cape Town. A suspended skeleton of a massive Plesiosaur dominates the ceiling space, its long neck and paddle-like limbs demonstrating perfect adaptation to marine life during the Mesozoic Era. Nearby displays feature the remains of mosasaurs, fearsome marine reptiles with powerful jaws that were the apex predators of the Late Cretaceous seas. The collection also includes remarkably preserved fossil specimens of ancient fish, including coelacanths (once thought extinct until discovered living off the South African coast in 1938) and various prehistoric sharks whose massive teeth suggest creatures far larger than today’s great whites. Detailed models recreate these extinct marine ecosystems, showing how these creatures interacted in the prehistoric oceans. The exhibition also traces the evolutionary connections between these ancient marine reptiles and today’s ocean fauna, highlighting both dramatic changes and surprising continuities.

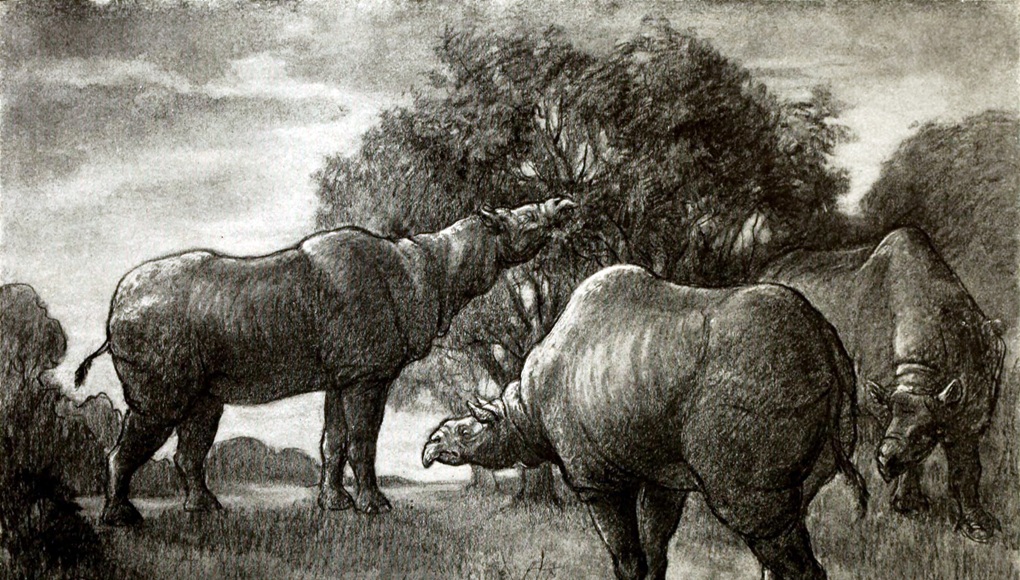

The Mega-Mammals of the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene gallery at Iziko South African Museum presents an astonishing array of giant mammals that roamed South Africa during the last ice age, approximately 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago. Visitors stand in awe before the reconstructed skeleton of the African giant buffalo (Pelorovis antiquus), which dwarfed modern Cape buffalo with its massive frame and spectacular curved horns spanning nearly two meters. The exhibition also features the remains of Sivatherium, a giraffid with moose-like antlers and the stature of a modern elephant, alongside fossils of giant hartebeest and prehistoric elephants with tusks significantly larger than their modern descendants. Particularly fascinating is the display on South Africa’s extinct giant baboon, Dinopithecus ingens, which stood nearly as tall as a modern human and weighed three times as much as today’s chacma baboons. Through careful curation, the museum illustrates how these mega-mammals adapted to changing climatic conditions during the Pleistocene, and explores the complex factors, including human hunting and habitat change, that may have contributed to their extinction.

The Taung Child: Humanity’s Ancient Relative

The Taung Child exhibit represents one of the most significant paleontological discoveries in South African history and a pivotal finding in understanding human evolution. This fossilized skull of a young Australopithecus africanus, discovered in 1924 in Taung, North West Province, forever changed our understanding of human origins by providing evidence that early hominids evolved in Africa. The museum’s display includes a cast of the original fossil (now housed at the University of the Witwatersrand) alongside detailed explanations of its anatomical features, including the brain case, dental development, and spinal cord position, which suggest bipedal locomotion. Interactive displays trace Professor Raymond Dart’s groundbreaking analysis of the skull and the initial skepticism his African origin theory faced from a scientific community previously convinced that human evolution occurred in Asia or Europe. The exhibit places the Taung Child within the broader context of hominin evolution, connecting it to other significant South African fossil sites like Sterkfontein and Kromdraai, which together form part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site known as the Cradle of Humankind.

Paleontological Fieldwork: Behind the Exhibits

The “Behind the Scenes” section of the museum offers visitors a fascinating glimpse into the painstaking process of paleontological fieldwork that brings ancient creatures from underground to exhibition halls. Through photographs, equipment displays, and video footage, visitors learn about the challenging conditions facing fossil hunters in the Karoo Basin, where summer temperatures regularly exceed 40°C (104°F) and winter nights drop below freezing. The exhibit demonstrates the careful excavation techniques employed to extract fragile fossils from rock matrices without damage, using specialized tools ranging from pneumatic drills to fine dental picks. Particularly impressive is the recreation of a field laboratory where visitors can observe the delicate preparation process, as technicians use air abrasion tools to remove stone from fossilized bone millimeter by millimeter. The museum highlights the contributions of not only renowned scientists but also the skilled local fossil preparators, many from rural communities near excavation sites, whose expertise and patience transform rough field specimens into scientifically valuable museum pieces through months or even years of meticulous work.

Fossil Formation: How Ancient Creatures Are Preserved

The taphonomy exhibit at Iziko South African Museum unravels the extraordinary process by which living organisms become preserved as fossils—a rare occurrence requiring specific conditions. Through clear diagrams and actual examples, visitors learn that most fossils form when organisms are quickly buried in sediment, protected from scavengers and decomposition, while minerals gradually replace organic materials in a process called permineralization. The exhibit showcases different types of preservation found in South African fossils, from the exquisitely detailed therapsid skeletons of the Karoo where even tiny ear bones remain intact, to trace fossils like footprints preserved in ancient mudstone. A particularly striking display demonstrates how the Karoo Basin’s unique geological history—alternating between floodplains, deltas, and dry periods—created ideal conditions for fossil formation over hundreds of millions of years. Interactive elements allow visitors to touch different types of fossilized materials and observe under microscopes the minute cellular structures sometimes preserved in the fossilization process, offering a tangible connection to creatures that lived hundreds of millions of years ago.

Dating the Past: How Scientists Determine Fossil Age

The “Dating the Past” section of the museum provides a comprehensive exploration of the scientific methods paleontologists use to determine the age of fossil specimens. The exhibit explains relative dating techniques, where fossils are dated based on their position in rock layers (stratigraphy) and their relationship to other fossils of known age. Visitors learn about index fossils—distinctive species with wide geographic distribution but short geological timespan—that help scientists correlate rock layers across different regions. The display also covers absolute dating methods, including radiometric dating techniques like uranium-lead and potassium-argon dating, which measure the decay of radioactive isotopes to calculate precise ages for volcanic rocks associated with fossil-bearing layers. Through clear models and interactive displays, the museum demonstrates how these various dating methods have been applied to South African fossil sites, establishing that the Karoo Basin fossils span from 300 to 180 million years ago. Particularly fascinating is the explanation of magnetostratigraphy, which uses the Earth’s periodically reversing magnetic field as recorded in rocks to create a timeline that can be correlated worldwide, helping to place South African fossils in global context.

Evolutionary Transitions: From Reptiles to Mammals

The evolutionary transitions gallery presents one of the museum’s most scientifically significant collections: the therapsids that document the gradual evolution from reptile-like creatures to true mammals. Through a series of fossil skulls arranged chronologically, visitors can observe the progressive changes that occurred over tens of millions of years during the Permian and Triassic periods. The exhibition traces the development of key mammalian characteristics, including the repositioning of jaw joints, evolution of specialized teeth for different diets, development of a secondary palate for simultaneous eating and breathing, and changes in posture from sprawling to upright limbs. A highlight of the collection is the remarkably complete skeleton of Thrinaxodon liorhinus, a advanced cynodont therapsid with many mammal-like features, discovered in the Karoo Basin and representing one of the closest relatives to true mammals. The museum’s displays explain how these evolutionary changes allowed therapsids to occupy new ecological niches, develop more active lifestyles, and ultimately survive the end-Permian mass extinction that eliminated approximately 96% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrates, setting the stage for the mammalian dominance that would follow millions of years later.

Ancient Cape Ecosystems: Reconstructing Past Environments

The paleoecology section of the museum offers a comprehensive reconstruction of Cape Town’s ancient ecosystems across different geological periods, based on meticulous analysis of fossil evidence. Detailed dioramas depict the lush Glossopteris forests of the Late Permian period, dominated by seed ferns and populated by a diverse array of therapsids, from small insectivores to large herbivores and their predators. Moving forward in time, visitors can explore the gradually changing Triassic landscapes where conifers began to replace seed ferns, and early dinosaurs competed with the remaining therapsids for ecological dominance. The exhibition employs cutting-edge paleobotanical evidence, including fossilized pollen, leaves, and wood, to accurately reconstruct ancient plant communities and climate conditions. Particularly innovative is the museum’s use of isotope analysis from fossil bones and teeth to determine ancient food webs and climate patterns, revealing that the Cape region experienced dramatic shifts from humid to arid conditions multiple times throughout its geological history. Interactive soil profile displays demonstrate how scientists analyze ancient soils (paleosols) for evidence of rainfall patterns, temperature ranges, and seasonal variations that affected the animals whose fossils now reside in the museum’s collection.

Mass Extinctions: When Life Nearly Ended

The mass extinction exhibit provides a sobering look at the five major extinction events that have dramatically altered life’s evolutionary trajectory, with particular focus on the End-Permian extinction (252 million years ago) that profoundly affected the creatures preserved in South Africa’s Karoo Basin. Through dramatic visual displays, visitors learn that this “Great Dying” eliminated an estimated 96% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species, making it the most severe extinction event in Earth’s history. The museum presents multiple lines of evidence for massive volcanic eruptions in what is now Siberia as the primary trigger, releasing enormous quantities of greenhouse gases that caused rapid global warming, ocean acidification, and widespread anoxic conditions. South African fossil beds provide some of the world’s best records of this catastrophic event, with clearly visible “extinction horizons” where diverse Permian fauna suddenly disappear from the fossil record. Particularly poignant is the display of Lystrosaurus, a tusked therapsid whose fossils dominate immediately after the extinction boundary, demonstrating how this hardy survivor exploited the ecological vacuum to become one of history’s most successful vertebrate species, comprising over 95% of land vertebrate fossils in early Triassic rocks before diversity gradually recovered.

Conservation and Modern Relevance: Learning from Ancient Life

The concluding section of the museum’s paleontological exhibition connects ancient extinctions to modern conservation challenges, drawing powerful parallels between past climate changes and current environmental concerns. Interactive displays compare the rate of species loss during prehistoric mass extinctions with current extinction rates, highlighting scientific estimates that suggest we may be entering a sixth mass extinction driven by human activities. The exhibition examines how studying the adaptive traits that allowed certain species to survive past extinction events can inform modern conservation strategies and climate resilience planning. Of particular relevance is the museum’s research on how ancient Cape fauna responded to climate fluctuations, providing potential insights into how modern African wildlife might adapt to current climate change. Digital interactive stations allow visitors to explore scenarios where lessons from paleontology are applied to contemporary conservation challenges in the Cape Floristic Region, one of the world’s biodiversity hotspots. The exhibit emphasizes that paleontology is not merely the study of ancient curiosities but a vital science that helps us understand ecosystem resilience, extinction vulnerability, and the long-term consequences of environmental change—lessons increasingly crucial as humanity faces unprecedented global challenges.

Conclusion: A Living Window to South Africa’s Ancient Past

The Iziko South African Museum stands as far more than a collection of ancient bones and fossils—it represents a dynamic narrative of life’s evolution in the Cape region across hundreds of millions of years. Through its world-class exhibitions, the museum connects visitors to creatures that once dominated landscapes now occupied by Cape Town’s urban sprawl and the surrounding wilderness areas. From the mammal-like reptiles of the Karoo to the early human ancestors of the Cradle of Humankind, these exhibits weave together the remarkable story of how life has evolved, adapted, and sometimes vanished throughout South Africa’s deep geological history. As both a scientific institution and a cultural treasure, the museum continues to play a vital role in education, research, and conservation, inviting each visitor to contemplate their own place in the ongoing story of life on Earth while gaining a profound appreciation for the ancient creatures that preceded us in this biologically remarkable corner of the African continent.