In the dense forests of the Late Jurassic period, approximately 150 million years ago, a small but formidable predator scurried through the underbrush, hunting insects and small vertebrates with remarkable agility. Compsognathus, whose name aptly translates to “elegant jaw,” may have stood no taller than a modern chicken, but this diminutive dinosaur has made an outsized impact on our understanding of dinosaur evolution, behavior, and the emergence of birds. Despite its modest stature—reaching only about two feet in length and weighing roughly five to seven pounds—Compsognathus represents a fascinating chapter in Earth’s prehistoric narrative, offering paleontologists crucial insights into the diversity of theropod dinosaurs during the Jurassic period.

Discovery and Historical Significance

Compsognathus has the distinction of being one of the first small theropod dinosaurs ever discovered, with the initial specimen found in the Solnhofen limestone deposits of Germany in the 1850s. Dr. Joseph Oberndorfer made the groundbreaking discovery, and the fossil was formally described by Johann A. Wagner in 1859, during the early days of paleontology when dinosaur science was still in its infancy. This timing proved significant, as the discovery of Compsognathus came just two years after Charles Darwin published “On the Origin of Species.” The remarkably preserved small dinosaur, with features reminiscent of both reptiles and birds, became a crucial piece of evidence in the emerging scientific debate about evolution and the relationship between dinosaurs and modern birds. Thomas Henry Huxley, a vocal supporter of Darwin, frequently referenced Compsognathus in his arguments for evolutionary theory, noting its similarities to the recently discovered Archaeopteryx from the same limestone formations.

Fossil Record and Preservation

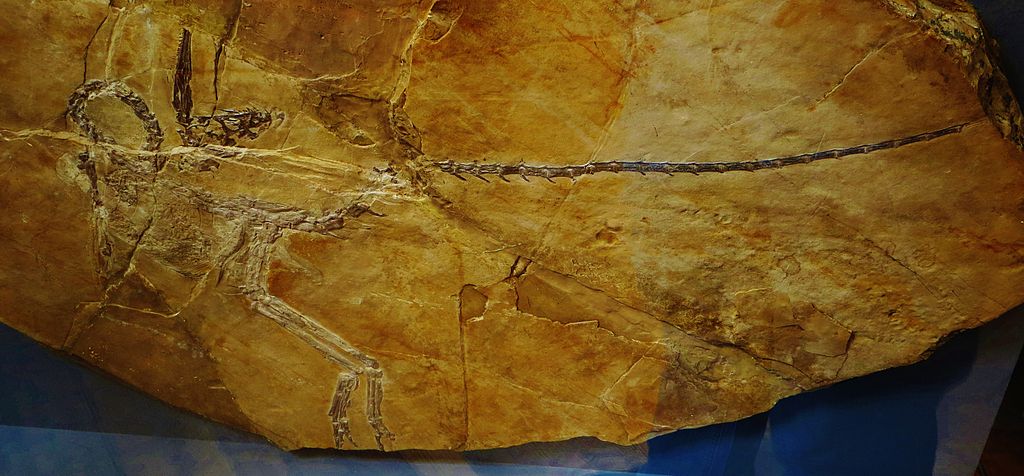

The fossil record of Compsognathus is exceptionally rare, with only two nearly complete specimens discovered to date—one from Germany and another from France. The remarkable preservation quality of these specimens owes to the fine-grained limestone deposits of the Solnhofen and Canjuers formations, which once formed the bottom of shallow lagoons where oxygen-poor conditions prevented significant decomposition. These Lagerstätten deposits preserved even delicate features like soft tissue impressions and minute bone structures, allowing paleontologists to study Compsognathus in extraordinary detail. The French specimen, discovered in the 1970s, is slightly larger than its German counterpart and provided additional anatomical information that was not apparent in the original fossil. Remarkably, both specimens were preserved with the remains of their last meals intact in their abdominal cavities, offering rare direct evidence of this dinosaur’s diet and hunting behavior.

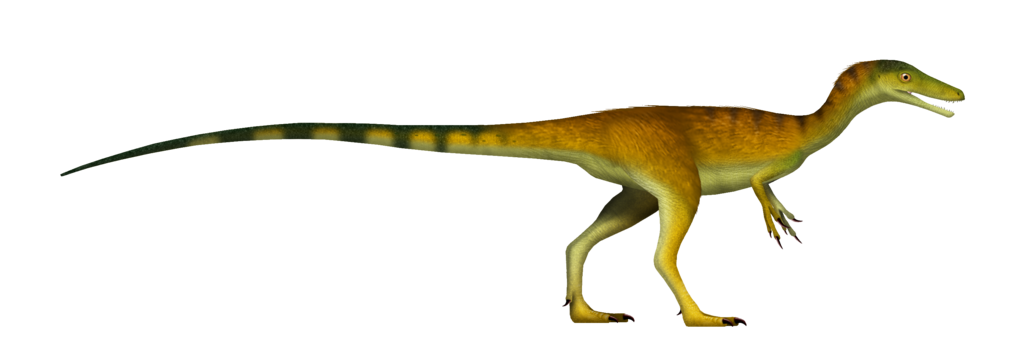

Anatomical Features and Physical Characteristics

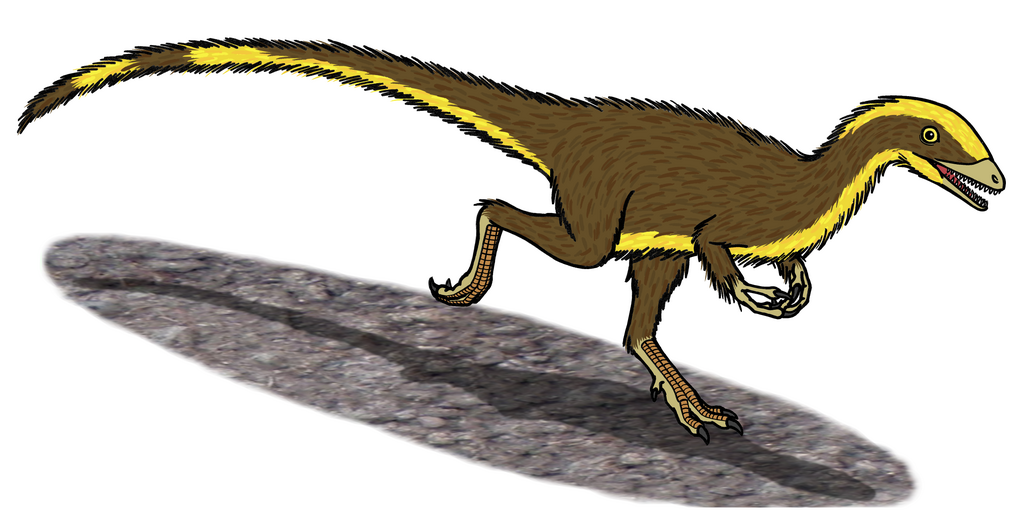

Compsognathus possessed a slender, lightweight skeleton perfectly adapted for agile movement and quick bursts of speed. Its body was streamlined, with a long, stiffened tail that would have provided balance and stability during rapid changes of direction when pursuing prey. The skull of Compsognathus was relatively small but featured rows of sharp, serrated teeth ideal for gripping and slicing through the flesh of small prey animals. Unlike many larger theropods, Compsognathus had proportionally longer hindlimbs compared to its forelimbs, suggesting it was an accomplished runner that primarily moved on its powerful back legs. Each hand possessed three fingers tipped with sharp claws, while the feet featured three primary weight-bearing toes, a characteristic hallmark of theropod dinosaurs. The lightweight construction of its skeleton included hollow bones with air sacs, a feature shared with modern birds, which would have reduced overall body weight while maintaining structural strength.

Phylogenetic Position and Evolutionary Significance

Compsognathus occupies a critical position in dinosaur phylogeny as a member of the Compsognathidae family, a group of small, primitive theropods closely related to the ancestry of birds. Initially, some scientists considered Compsognathus a direct ancestor to birds due to its small size and certain skeletal features, though modern cladistic analyses have refined this understanding. Today, paleontologists place Compsognathus within the larger clade of coelurosaurs, the diverse group of theropods that includes both tyrannosaurs and the direct ancestors of birds. Its position in the evolutionary tree makes Compsognathus important for understanding the sequence of anatomical changes that occurred as certain dinosaur lineages evolved toward bird-like features. Though not in the direct line to birds, Compsognathus demonstrates an early stage in the evolution of features that would later become modified in avian dinosaurs, including its lightweight skeleton, relatively large brain, and potentially even primitive integumentary structures (though direct evidence for feathers in Compsognathus remains controversial).

Diet and Hunting Behavior

Dietary evidence for Compsognathus comes directly from fossilized stomach contents, offering a rare window into the actual feeding habits of this diminutive predator. Both known specimens contain the remains of small prey animals in their abdominal cavities—the German specimen preserved with lizard remains, while the French specimen appears to have consumed either a small lizard or possibly a juvenile dinosaur. These preserved last meals confirm that Compsognathus was an active predator that hunted small vertebrates, not merely an insectivore as was once hypothesized based on its size. The structure of its jaws and teeth—sharp, curved, and serrated—were perfectly adapted for seizing and holding struggling prey before delivering killing bites. As a fast, agile hunter, Compsognathus likely employed a hunting strategy that involved quick bursts of speed to chase down small, swift prey in the dense Jurassic underbrush. Its large eyes positioned on the sides of its skull would have provided excellent vision for spotting movement, while its relatively large brain may have allowed for more complex hunting behaviors than seen in earlier theropods.

Habitat and Environmental Context

During the Late Jurassic period, the regions where Compsognathus fossils have been discovered were vastly different from the European continent we know today. Both the German and French localities represent what were once archipelagos—island environments surrounded by shallow, warm lagoons within a larger tropical sea. The climate was warmer and more humid than modern Europe, creating lush coastal forests where Compsognathus would have thrived alongside a diverse array of other Jurassic creatures. The Solnhofen limestone in particular preserves evidence of a complex ecosystem including flying pterosaurs, early birds like Archaeopteryx, various marine reptiles, fish, invertebrates, and a range of plant life. Compsognathus likely inhabited the forested regions of these islands, where the dense vegetation would have provided both cover for hunting and protection from larger predators. The isolated island environments may partially explain the small size of Compsognathus, as island ecosystems often favor the evolution of smaller body sizes in larger animals, a phenomenon known as island dwarfism.

Speed and Agility

Biomechanical studies of Compsognathus’s skeletal structure suggest it was built for speed and maneuverability, capable of reaching impressive velocities for its size. Scientists estimate that this dinosaur could have reached running speeds of approximately 40 kilometers per hour (25 mph), making it one of the faster small dinosaurs of its time. The lightweight construction of its skeleton, with hollow, pneumatic bones and a stiffened tail for balance, would have minimized weight while maximizing locomotive efficiency. Its proportionally long hindlimbs, with their digitigrade (toe-walking) posture and bird-like feet, were ideal for maintaining balance during rapid changes in direction when pursuing elusive prey through dense undergrowth. Muscle attachment points visible on fossil specimens indicate powerful leg muscles that would have provided the necessary force for quick acceleration, an essential adaptation for a predator specializing in catching fast-moving small prey. The agility of Compsognathus would have made it a formidable hunter in its ecological niche, able to outmaneuver the lizards and small mammals that formed its primary diet.

Social Behavior and Reproduction

The social behavior of Compsognathus remains largely speculative due to the limited fossil evidence, though certain inferences can be drawn from its anatomy and comparisons with related theropods. The relatively large brain size for its body suggests a level of behavioral complexity that might have included some form of social interaction, potentially including coordinated hunting or territorial behavior. Unlike some larger theropods that show evidence of pack hunting, Compsognathus was likely primarily solitary or operated in loose associations, given its small size and presumed hunting strategy focused on small prey that wouldn’t require group tactics. Regarding reproduction, no Compsognathus nests or eggs have been discovered, though the reproductive biology was likely similar to other small theropods, involving the laying of relatively small eggs in prepared ground nests. Parental care may have been present to some degree, as is suspected for many theropod dinosaurs based on comparisons with modern birds and crocodilians, the closest living relatives of dinosaurs. The growth rate was probably rapid, with juveniles reaching adult size within a few years, a pattern common among smaller dinosaur species.

Comparison with Contemporary Dinosaurs

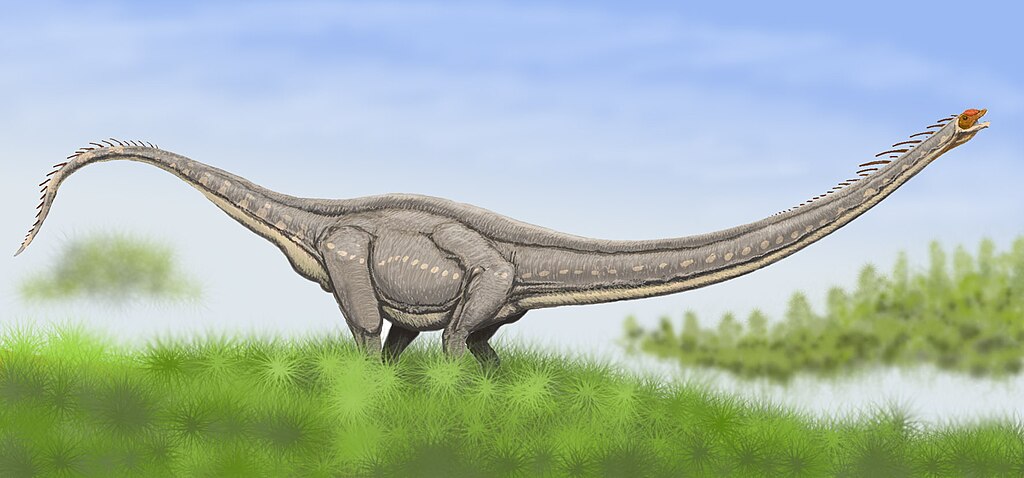

The Late Jurassic ecosystem where Compsognathus lived featured a remarkable diversity of dinosaur species, creating a complex network of ecological relationships. While giant sauropods like Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus dominated the landscape as massive herbivores, and large theropods like Allosaurus reigned as apex predators, Compsognathus occupied a distinct niche as a small, active predator of very small vertebrates. Contemporary small theropods included Ornitholestes and various dromaeosaurids, though these were generally larger than Compsognathus and likely targeted different prey. The earliest birds, such as Archaeopteryx, shared the Solnhofen environment with Compsognathus, and the similarities between these animals highlight the evolutionary connections between non-avian dinosaurs and birds. Interestingly, the small size of Compsognathus means it likely faced predation pressure itself from larger theropods and possibly even pterosaurs, positioning it as both predator and prey within the complex Jurassic food web. This ecological position may explain adaptations for speed and stealth that would have helped it both capture prey and avoid becoming prey itself.

Popular Culture Representations

Despite its diminutive size, Compsognathus has achieved notable fame in popular culture, particularly through its memorable appearances in the Jurassic Park and Jurassic World film franchises. In “The Lost World: Jurassic Park,” a pack of aggressive Compsognathus (affectionately dubbed “compys” in the film) was portrayed attacking a young girl and later a villainous character, creating a memorable if scientifically inaccurate depiction of pack-hunting behavior. This portrayal significantly raised the public profile of Compsognathus, though it exaggerated both the social behavior and the aggressiveness of these small dinosaurs. Beyond cinema, Compsognathus regularly appears in dinosaur books, museum exhibits, and educational materials, often used to illustrate the diversity of dinosaur sizes and to counter the common misconception that all dinosaurs were gigantic. The dinosaur has also featured in various video games, including entries in the Jurassic World Evolution series, where players can manage these small theropods in virtual dinosaur parks. These cultural representations, while not always scientifically accurate, have helped make Compsognathus one of the most recognizable small dinosaurs to the general public.

Integumentary Covering and the Feather Debate

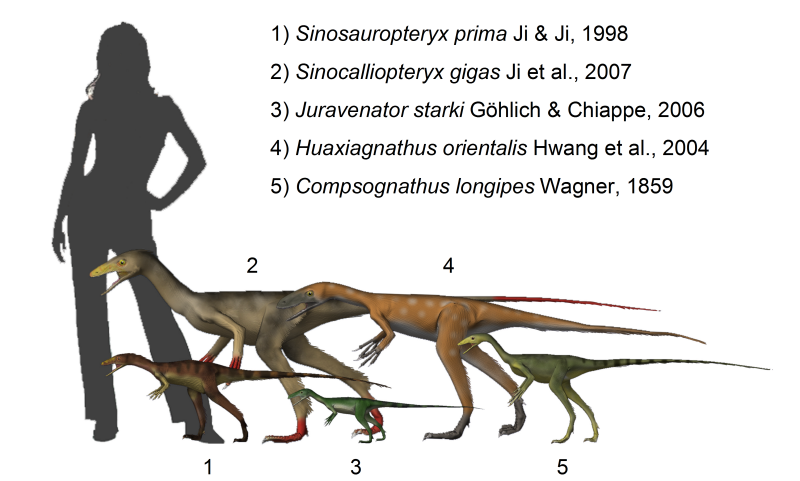

One of the most intriguing questions surrounding Compsognathus involves what covered its skin—scales, primitive feathers, or some combination of both. Despite the exceptional preservation of the known specimens, neither shows definitive evidence of integumentary structures beyond impressions once interpreted as scales. However, the discovery of feathered relatives of Compsognathus from Chinese deposits, particularly Sinosauropteryx, has prompted paleontologists to reconsider whether Compsognathus might have possessed some form of filamentous proto-feathers as well. Sinosauropteryx, a very close relative with remarkably similar anatomy, clearly shows preservation of simple, hair-like feather structures covering much of its body. The lack of such preservation in Compsognathus specimens may be due to taphonomic factors—the specific conditions of fossilization—rather than an actual absence of such structures in life. Current scientific consensus leans toward Compsognathus having at least some feather-like covering, particularly given its phylogenetic position among coelurosaurian theropods, a group now widely recognized as being predominantly feathered. If present, these structures would likely have served primarily for insulation rather than display or flight, helping this small dinosaur regulate its body temperature.

Thermoregulation and Metabolism

The question of Compsognathus’s metabolism has evolved considerably as our understanding of dinosaur physiology has advanced. While dinosaurs were once viewed as essentially cold-blooded reptiles, contemporary scientific evidence strongly supports that many dinosaurs, particularly theropods like Compsognathus, possessed elevated metabolic rates closer to those of modern birds than to reptiles. The lightweight, hollow bone structure of Compsognathus suggests an active lifestyle that would have required efficient oxygen delivery and energy production systems. Microscopic examination of bone tissue from related theropods shows growth patterns consistent with sustained high metabolic rates, unlike the stop-and-start growth seen in most reptiles. If Compsognathus did indeed possess feather-like integumentary structures as many scientists now believe, these would have provided crucial insulation to maintain body heat, further supporting an endothermic or at least partially endothermic metabolism. Such a metabolic strategy would have allowed Compsognathus to remain active even during cooler periods and would have supported the quick bursts of speed needed for its predatory lifestyle, though it would have required a proportionally higher food intake than a comparable cold-blooded animal.

Extinction and Legacy

The specific fate of Compsognathus as a genus remains unclear, though the species likely disappeared as part of broader ecological changes during the Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous transition. While not victims of the famous end-Cretaceous mass extinction that claimed the non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago, the compsognathids eventually gave way to other small theropod groups that radiated throughout the Cretaceous period. The ecological niche that Compsognathus occupied—small, fast-running predators of very small vertebrates—continued to be filled by various other dinosaur lineages, particularly the dromaeosaurids and troodontids, which evolved increasingly sophisticated adaptations for this hunting lifestyle. Though extinct for approximately 145 million years, Compsognathus has left an enduring scientific legacy as one of the first small theropods discovered, challenging early conceptions that all dinosaurs were gigantic behemoths. Its well-preserved fossils continue to provide valuable insights into dinosaur anatomy, ecology, and the evolutionary pathway toward birds. Modern paleontological techniques, including CT scanning and microscopic analysis, continue to extract new information from the original specimens, ensuring that Compsognathus remains relevant to scientific inquiry nearly 170 years after its initial discovery.

Recent Research and Continuing Discoveries

The scientific understanding of Compsognathus continues to evolve as new analytical techniques allow researchers to extract more information from existing specimens. Recent studies using advanced imaging technologies such as micro-CT scanning have revealed previously unobserved details of its cranial anatomy and brain case structure, providing new insights into its sensory capabilities and neurological development. Biomechanical modeling, employing computer simulations to analyze how its skeleton would have functioned in life, has refined our understanding of its movement patterns and speed capabilities. Additionally, comparative studies with newly discovered small theropods from China and elsewhere have helped clarify Compsognathus’s phylogenetic relationships and evolutionary significance. Geochemical analyses of bone tissue have provided clues about its growth rate and metabolic activity, supporting theories about warm-blooded physiology. While no new Compsognathus specimens have been discovered in recent decades, the reexamination of existing fossils with these cutting-edge techniques continues to yield fresh insights, demonstrating that even long-studied dinosaur specimens can reveal new secrets when subjected to emerging scientific methods.