You’re probably picturing massive sea monsters from prehistoric times lurking in the darkest corners of our oceans. The idea sounds like something straight out of science fiction, yet given how little we know about the deep sea, you might wonder if it’s entirely impossible. What secrets could be hiding in the trenches that plunge deeper than Mount Everest is tall?

Scientists keep discovering life where they least expect it, and these findings constantly challenge what we thought we knew about survival in extreme environments. Let’s dive into this fascinating mystery and see what the evidence really tells us.

The Vastness of the Unexplored Deep Sea

Humans have explored just 0.001 percent of the deep seafloor below 656 feet, an area roughly the size of Rhode Island out of an ocean covering most of our planet. Think about that for a moment. Roughly four fifths of the global hadal zone remains a mystery, representing one of Earth’s last true frontiers. The ocean trenches are among the least accessible places on our planet.

Ocean trenches remain one of the most elusive and little-known marine habitats, and until the 1950s, many oceanographers thought these trenches were unchanging environments nearly devoid of life. Even today, most research relies on limited seafloor samples and photographic expeditions rather than direct observation. The deep sea remains largely unexplored, and this ignorance leaves room for possibilities you might not expect.

Ancient Marine Reptiles: Giants That Ruled Prehistoric Seas

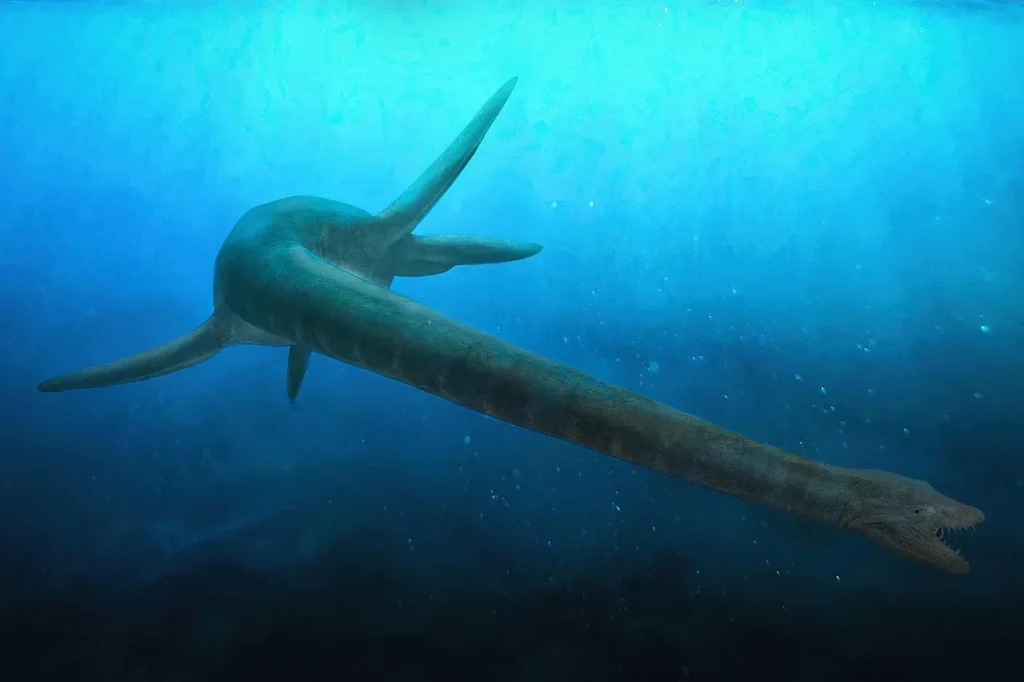

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period about 203 million years ago, becoming especially common during the Jurassic Period and thriving until their disappearance due to the extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous Period about 66 million years ago. These weren’t small creatures either. Some species reached lengths of up to seventeen meters, making them apex predators that dominated their marine environments. Their distinctive long necks and powerful flippers made them perfectly adapted hunters.

Mosasaurs are considered the Great Marine Reptiles of the Cretaceous, though other great marine reptiles that predated them included dolphin-like ichthyosaurs, long-necked plesiosaurs, and short-necked pliosaurs. Mosasaurs were gigantic marine lizards that grew as large as whales and became the biggest predators of the Cretaceous oceans in just 25 million years. Think of them as the ocean’s ultimate predatory machines, perfectly designed for their watery realm.

The Coelacanth Lesson: Extinct Until It Wasn’t

Here’s where things get interesting. Coelacanths were believed to have become extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period, until a specimen was found off the east coast of South Africa on December 22, 1938. This fish had supposedly been gone for more than 60 million years. Its discovery makes the coelacanth the best-known example of a Lazarus taxon, an evolutionary line that seems to have disappeared from the fossil record only to reappear.

Coelacanths were once thought to have gone extinct approximately 65 million years ago during the great extinction in which the dinosaurs disappeared, until a live specimen was caught in a fishing trawl in 1938. The scientific community was absolutely stunned. If a large fish could hide from humanity for millions of years, what else might be lurking undetected? It was believed to have vanished along with the dinosaurs, but only two species have been confirmed since: Latimeria chalumnae in the western Indian Ocean and Latimeria menadoensis in Indonesian waters.

Thriving Life at Crushing Depths

A Chinese submersible discovered thousands of worms and mollusks nearly 10 kilometers below sea level in the Mariana Trench, with colonies observed at depths up to 9,533 meters, marking the deepest and most extensive chemosynthesis-based ecosystems known. You read that right: nearly six miles down, where the pressure would crush most things instantly. These creatures don’t rely on sunlight but instead live off chemicals like methane seeping through cracks in the seafloor.

In total darkness at the bottom of the world, these creatures live off chemicals such as methane through a process called chemosynthesis, with organisms relying on chemical energy produced by microbes rather than sunlight. The study found an unprecedented level of taxonomic novelty, with 89.4 percent of identified microbial species previously unreported. The hadal zone is far from the desolate wasteland scientists once imagined. It’s teeming with unexpected life forms.

Physical Barriers and Biological Limits

Let’s be real: there are massive problems with large marine reptiles surviving at extreme depths. Pressure at the bottom of the Challenger Deep is about 12,400 tons per square meter, and large ocean animals such as sharks and whales cannot live at this crushing depth. Ancient reptiles needed to breathe air at the surface, just like modern marine mammals do. Mosasaurs were reptiles, which means they had to surface to breathe air, like a sea turtle today.

Even the fish in deep trenches are gelatinous, with several species of bulb-headed snailfish dwelling at the bottom of the Mariana Trench having bodies compared to tissue paper. The creatures that survive down there have undergone extraordinary adaptations over millions of years. A plesiosaur or mosasaur built for surface hunting simply wouldn’t have the body structure to withstand those conditions. Their bones, their air-breathing lungs, their whole physiology evolved for different environments entirely.

Rare Deep-Sea Discoveries That Surprise Scientists

The first megamouth shark was captured on November 15, 1976, when it became entangled in a Navy ship’s sea anchor at about 165 meters depth, making it one of the more sensational discoveries in 20th-century ichthyology. This massive filter-feeding shark was completely unknown to science until fairly recently. Only 296 megamouth specimens had been caught or sighted as of March 2025, and they have been found in the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans.

Scientists discovered a new crustacean species in the Atacama Trench at 8,000 meters deep, revealing the Hadal zone as a potential haven for hidden marine life, with genomic testing confirming it as a new genus. New species keep appearing in places scientists never thought to look. The ocean clearly still holds secrets. What fascinates me is how these discoveries happen almost by accident, suggesting countless more organisms remain undetected.

Why Large Reptiles Are Unlikely in the Trenches

Food scarcity poses a monumental challenge. Without photosynthesis, marine communities in trenches rely primarily on marine snow, the continual fall of organic material from higher in the water column. Large predators require substantial energy and food sources to survive. Ancient marine reptiles were apex predators hunting fish, cephalopods, and other large prey. The deep trench ecosystems simply don’t support that kind of food web.

Temperature is another factor you can’t ignore. By 13,000 feet, the temperature hovers just below refrigerator temperature, and the water temperature is near freezing. Marine reptiles were likely more active in warmer waters where prey was abundant. Their metabolic needs would make survival in frigid, food-poor trenches nearly impossible. Honestly, the physics and biology just don’t add up for creatures designed to thrive in completely different conditions.

What Scientists Actually Find in the Abyss

Scientists discovered thriving communities of marine life including thousands of worms and mollusks nearly six miles beneath the surface, dominated by tube worms and clams surviving through chemosynthesis. The discovery by a Chinese-led research team at depths around 31,000 feet represents the deepest and most extensive communities of chemical-reaction-powered life forms known, with communities dominated by marine tubeworms and mollusks synthesizing energy using hydrogen sulfide and methane.

The hadal snailfish with delicate fins and translucent body roams the dark freezing waters, while giant shrimp-like creatures up to a foot long scavenge fallen debris, and transparent eels with fish-like heads hunt prey. These are the creatures adapted to the abyss: small, gelatinous, energy-efficient organisms. Not massive air-breathing reptiles from the age of dinosaurs. The evidence consistently points toward specialized deep-sea life forms, not relict populations of extinct surface dwellers.

The Verdict: Fascinating but Implausible

The romantic notion of plesiosaurs or mosasaurs hiding in ocean trenches captures our imagination precisely because the deep sea remains so mysterious. We’ve learned that unexpected life thrives in the most extreme environments on Earth. The coelacanth’s rediscovery proves that large creatures can evade detection for surprisingly long periods. Recent expeditions continue revealing bizarre new species that challenge our assumptions about what’s possible.

However, the biological requirements of large marine reptiles make their survival in deep trenches essentially impossible. They needed to breathe air regularly. They required abundant prey. They evolved for entirely different pressure, temperature, and food conditions. While the ocean certainly holds undiscovered species, they’re more likely to be specialized deep-sea organisms than refugees from the Mesozoic Era. The trenches are indeed full of life, just not the kind that roamed shallow Cretaceous seas.

What do you think? Would you hope to find a living plesiosaur in the depths, or do you find the creatures we’re actually discovering just as fascinating?