Have you ever looked up at a crystal clear night and felt a sense of awe at the infinite expanse above you? You might wonder if people centuries ago had the same feeling or if they saw something more than just twinkling lights. Think about it. Without telescopes, computers, or satellites, our ancestors managed to track celestial movements with startling precision. Ancient North American civilizations weren’t just stargazers passing time around campfires. They were skilled astronomers who wove the movements of the cosmos into every aspect of their lives.

From predicting seasonal changes to marking significant ceremonies, the sky became their calendar, their compass, and their connection to the divine. Let’s be real, the depth of their astronomical knowledge challenges everything you thought you knew about ancient peoples and their capabilities. So, let’s dive in.

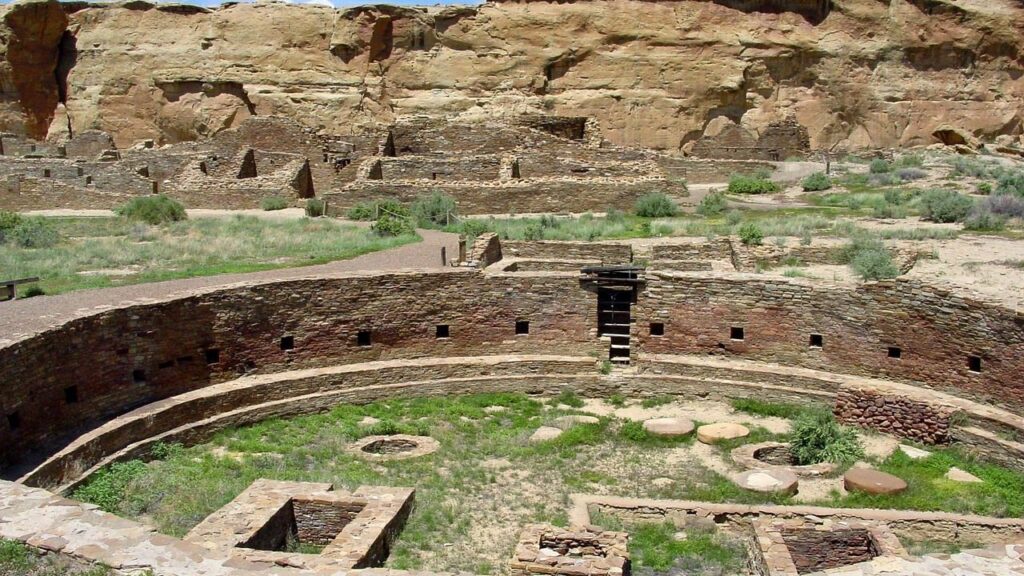

The Cosmic Calendar Carved in Stone

Imagine standing in Chaco Canyon on a summer morning roughly a thousand years ago. You’d watch as the Ancestral Pueblo people carved petroglyphs and painted pictographs to follow the cycle of the sun, moon, and stars, along with equinoxes and solstices. These weren’t just pretty pictures etched onto rock surfaces. They were functional astronomical tools that helped entire communities synchronize their lives with celestial rhythms.

A petroglyph at Chaco Culture National Historical Park may represent a total solar eclipse that took place on July 11, 1097, showing a filled circle with squiggly lines extending around its edge and a small filled circle to the upper left, possibly illustrating the sun in total eclipse and the planet Venus. Here’s the thing. These ancient astronomers documented events with such accuracy that modern researchers can still identify specific celestial occurrences from their stone records. The precision required to track and record such fleeting moments demands years, if not generations, of dedicated observation.

Architectural Marvels Aligned With the Heavens

Research by the Solstice Project has shown that twelve of the Chacoans’ major buildings, eight in Chaco Canyon and the four largest outlying structures, are oriented to the solar and lunar cycles. Think about the level of planning that requires. You’re not just putting up a building. You’re embedding astronomical knowledge into every wall, every doorway, every ceremonial space.

Seven buildings in Chaco Canyon have alignments with the maximum and minimum risings and settings of the Moon, and no other culture in the world is known to build structures in alignment with this long cycle. Let that sink in for a moment. The lunar standstill cycle takes roughly nineteen years to complete, and these builders designed structures to capture those extreme positions on the horizon. This wasn’t accidental placement. It was sophisticated engineering combined with deep astronomical understanding that took lifetimes to perfect.

The Sun Dagger: A Celestial Clock of Precision

High atop Fajada Butte sits one of the most remarkable ancient astronomical devices ever discovered. Three stone slabs positioned just so create shafts of light that interact with a spiral petroglyph carved into the cliff face. The arrangement had a streak of light bisecting the spiral during the summer solstice, and on the equinox, not one but two light shafts would flank the edges of the spiral.

When the Moon reaches minimum extreme, its shadow falls in the center of the spiral where the sun dagger appears on the summer solstice, and when it’s at maximum extreme nearly a decade later, its shadow falls on the outer edge where the sun dagger appears at winter solstice, with the spiral having roughly nine and a half turns. The genius here lies not just in observing these cycles, but in creating a permanent marker that could teach future generations. You didn’t need to spend decades learning the patterns. The stone itself became the teacher.

Tracking Extraordinary Cosmic Events

Beyond the predictable cycles of sun and moon, ancient North Americans also documented rare and spectacular celestial phenomena. A pictograph shows the waning moon and an exploding star, visible during the day for over three weeks, with the hand possibly pointing to the horizon where the supernova rose an hour and forty five minutes before sunrise. This likely depicts the supernova of 1054, an event so bright it was recorded by observers across the world.

The Pueblo descendants of the Mesa Verde and Chaco people studied the sun and were able to predict eclipses and to track Halley’s Comet. Honestly, predicting eclipses without modern instruments demonstrates an understanding of celestial mechanics that rivals many later civilizations. In Plains Indian Winter Counts, Indigenous historians recorded comets and eclipses as events worthy of note. These weren’t just random observations. They were systematic records passed down through generations, each adding to the collective astronomical knowledge.

Medicine Wheels and Earthen Observatories

In North America, structures like medicine wheels, found primarily in the Rocky Mountain region, serve as ancient astronomical observatories, marking key solar events. These stone circles might look simple at first glance, yet their positioning reveals careful consideration of celestial alignments. Picture yourself as a member of one of these communities, watching the sunrise through specific stones to know exactly when to begin planting crops.

Earthen mounds in the Mississippi and Ohio river valleys showcase a connection to celestial patterns, with some aligning with the stars of the Big Dipper. At Cahokia, Missouri, where 120 earthen mounds formed a large village, a circle of cedar posts marked sunrise solstices and the equinox, a site archaeologists have nicknamed Woodhenge, after Stonehenge. The scale and ambition of these projects reveal societies with surplus resources, organized labor, and most importantly, a driving need to understand and mark cosmic time.

The Living Sky in Indigenous Cosmology

The indigenous North American people viewed the sun, the moon, and the stars as a way to integrate human behavior and nature, with celestial objects believed to reveal the fundamental order of the world. This wasn’t abstract philosophy. It was practical wisdom encoded in stories, ceremonies, and daily activities. The cosmos wasn’t something separate from earthly existence. It was intimately woven into every aspect of life.

The Skidi Pawnee arranged their villages in the pattern of the North Star, evening star, and morning star, and they arranged the posts of their earthen lodges in the same pattern, so each home repeated the cosmic arrangement. Imagine living in a dwelling where the very structure reminds you of your place in the universe. These civilizations felt a connection between stars, the sun and the moon, and the clouds in the sky, feeling kinship with everything they saw around them on some level. This holistic worldview created a different kind of science, one where observation and spirituality weren’t separate domains but complementary ways of understanding reality.

Methods of Observation and Knowledge Transfer

How did they do it without modern technology? Through careful observation, generational record keeping, pattern recognition and early mathematics. It sounds straightforward when you say it like that, but think about the dedication required. Generation after generation watching the same patch of sky, noting the same celestial events, refining predictions, and passing that knowledge forward.

Indigenous peoples around the world, including those in North America, Australia, and Polynesia, had complex oral traditions that recorded repeating sky phenomena, often linking eclipses to rituals, agricultural timing, or cosmic cycles, with their observational knowledge being profound and often encoded in myths, petroglyphs, and story cycles passed down for generations. The oral tradition served as their library, their textbook, their scientific journal all rolled into one. The astronomer Anna Sofaer called buildings at Chaco Canyon “cosmological expression through architecture,” noting that some Indigenous peoples could predict astronomical events with great precision. The evidence speaks for itself. These weren’t primitive societies stumbling through the dark. They were sophisticated cultures with systematic approaches to understanding the cosmos.

Conclusion: A Legacy Written in the Stars

So The archaeological and astronomical evidence provides a resounding answer. Yes, they absolutely could. From tracking the intricate dance of the lunar standstill cycle to marking solstices with architectural precision, from documenting supernovas to predicting eclipses, these cultures demonstrated astronomical capabilities that rival any civilization of their time.

Their observatories weren’t made of brass and glass, but of stone and earth and careful positioning. Their records weren’t written in journals, but carved in rock and woven into stories. Their understanding of the cosmos informed everything from agriculture to architecture, from navigation to spiritual practice. The sophistication of their astronomical knowledge challenges modern assumptions about the progression of scientific understanding.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect is how this knowledge was preserved and transmitted across generations without written language as we understand it. These civilizations created living traditions where the sky became both teacher and sacred text. What would it be like if you still looked at the night sky with that same blend of practical knowledge and spiritual reverence? How might your understanding of the universe change if you spent even a fraction of the time our ancestors did simply watching and learning from the heavens above?