Picture this: a massive Tyrannosaurus rex, all seven tons of predatory muscle, cautiously wading into an ancient river. It sounds almost absurd, doesn’t it? Yet the question of whether dinosaurs could swim has captivated paleontologists for decades. While we often imagine these magnificent creatures stomping across dry land, the reality is far more nuanced and fascinating. Recent discoveries have shattered many assumptions about dinosaur capabilities, revealing that some were surprisingly adept swimmers while others would have sunk like stones.

The Physics of Prehistoric Swimming

When we think about swimming dinosaurs, we first need to understand the basic physics involved. Body density plays a crucial role in determining whether any animal can float or swim effectively. Dinosaurs with hollow bones, like many theropods, had a significant advantage in the water compared to their solid-boned relatives.

The relationship between body mass and buoyancy created interesting challenges for different dinosaur species. Larger dinosaurs faced greater difficulties due to their massive weight, while smaller, lighter species could potentially navigate water with greater ease. Air-filled bones, similar to those found in modern birds, would have acted like natural life preservers for certain dinosaur groups.

Spinosaurus: The Undisputed Aquatic Champion

Among all dinosaurs, Spinosaurus stands out as the most convincing swimmer. This massive predator possessed a paddle-like tail, webbed feet, and dense bones that helped it stay submerged while hunting. Its elongated snout, filled with conical teeth, was perfectly designed for catching fish in ancient rivers.

Recent fossil evidence has revealed that Spinosaurus spent considerable time in water, making it the first known semi-aquatic dinosaur. Its nostrils were positioned high on its skull, allowing it to breathe while mostly submerged. The distinctive sail on its back may have even served as a dorsal fin, providing stability while swimming through prehistoric waterways.

Duckbilled Dinosaurs and Their Aquatic Adaptations

Hadrosaurs, commonly known as duck-billed dinosaurs, possessed several features that suggest they were comfortable in water. Their webbed fingers and paddle-like tails would have been excellent for propulsion through rivers and lakes. These herbivores likely used water as both a food source and escape route from predators.

The flat, broad bills of hadrosaurs were perfectly suited for filtering aquatic vegetation, much like modern waterfowl. Their ability to walk on both two and four legs gave them versatility when transitioning between land and water environments. Fossil trackways have even been found showing hadrosaurs entering and exiting ancient water bodies.

Theropods: Surprisingly Capable Swimmers

Many theropod dinosaurs, despite their fearsome reputations, were likely decent swimmers. Their hollow bones provided natural buoyancy, while their powerful leg muscles could generate sufficient thrust for propulsion. Smaller theropods like Compsognathus probably swam with relative ease, using their long tails for steering.

Even larger theropods like Allosaurus and Carnotaurus may have been capable swimmers when necessary. Their streamlined bodies and muscular tails would have helped them navigate water, though they likely preferred to stay on dry land. Swimming would have been particularly useful for crossing rivers or pursuing prey into aquatic environments.

Sauropods: The Floating Giants

The enormous sauropods present one of the most intriguing cases in dinosaur swimming discussions. These massive herbivores, weighing up to 80 tons, were once thought to be too heavy for terrestrial life. Early paleontologists actually believed they lived primarily in water to support their tremendous weight.

Modern research suggests that while sauropods could likely float due to their size and air-filled bones, they were probably poor swimmers. Their massive bodies and relatively small limbs would have made coordinated swimming movements extremely difficult. However, they could have waded through shallow water and possibly floated across deeper sections when necessary.

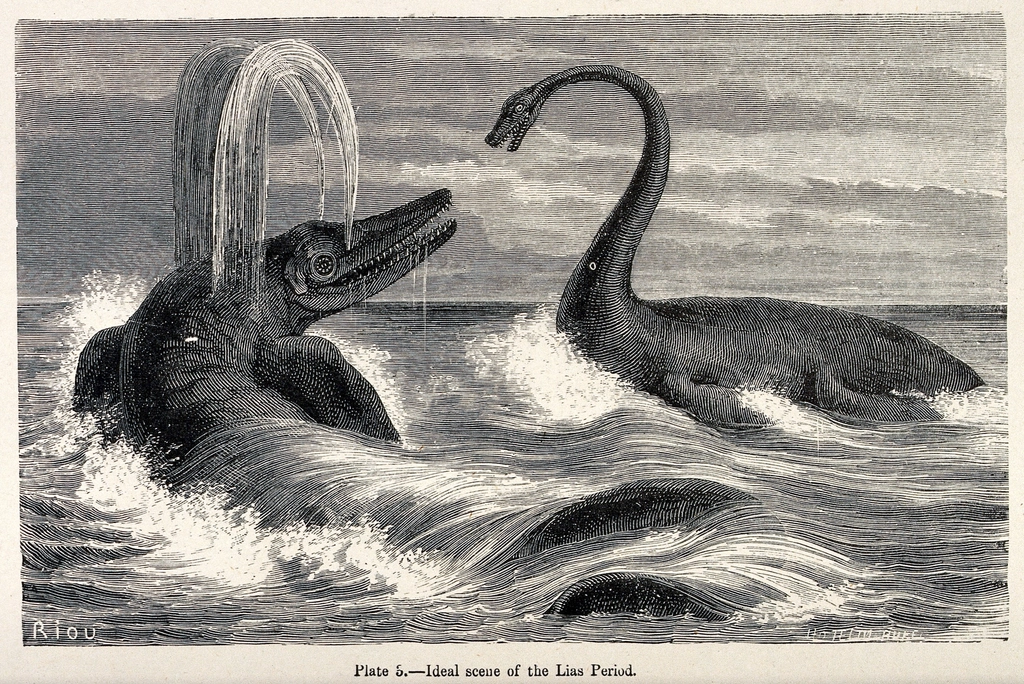

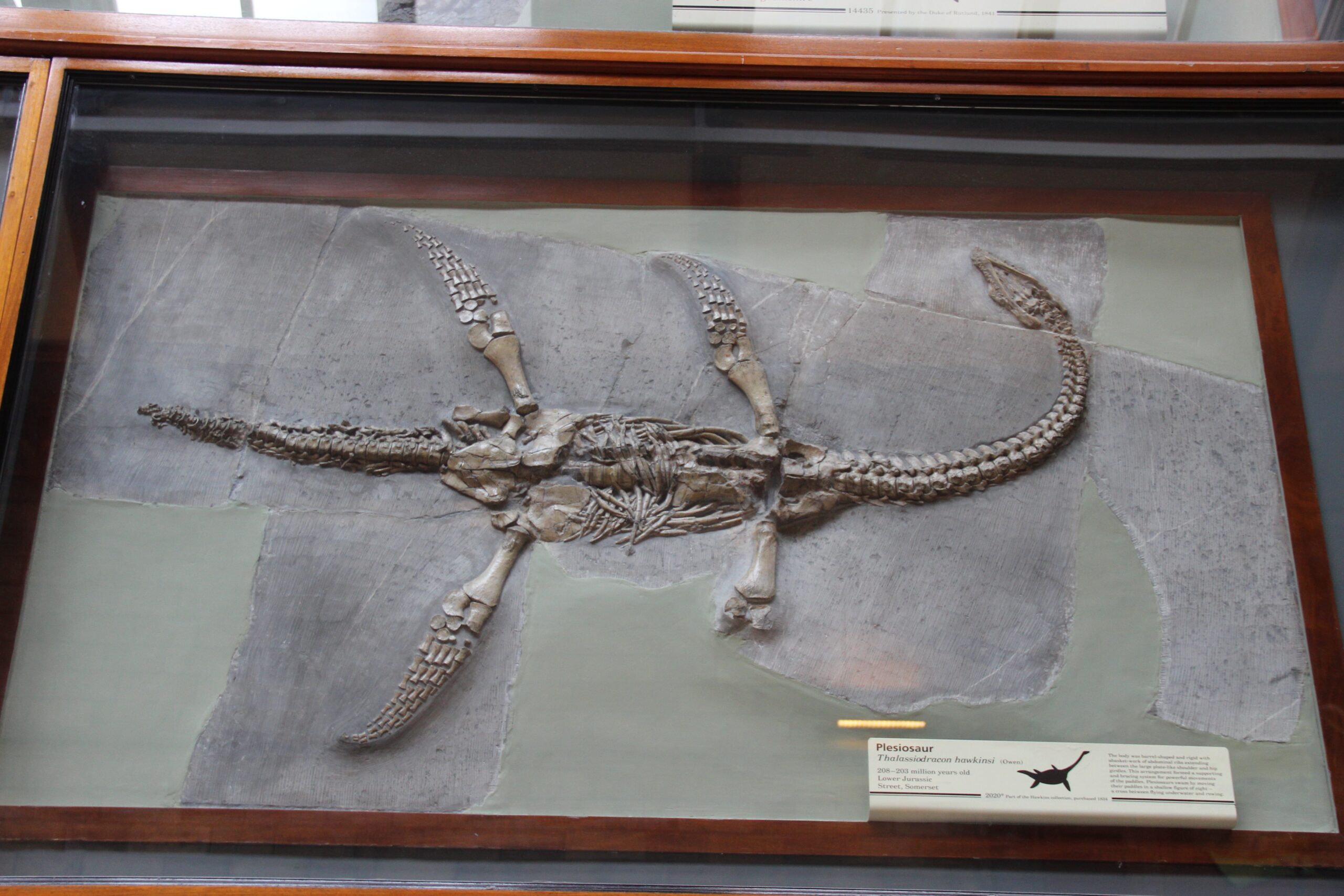

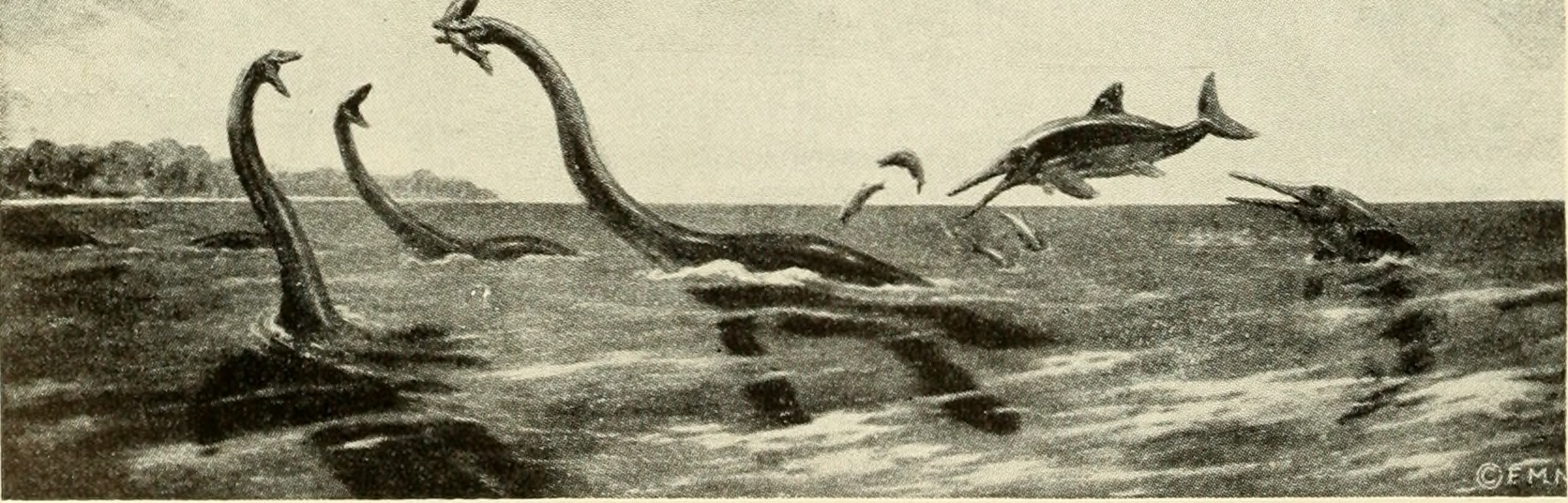

Plesiosaurs: The Marine Specialists

While technically not dinosaurs, plesiosaurs lived during the same time period and represent the pinnacle of aquatic adaptation among prehistoric reptiles. These marine reptiles had four large flippers and streamlined bodies perfectly designed for life in the ocean. Their swimming style resembled that of modern sea turtles, using powerful strokes to propel themselves through the water.

Long-necked plesiosaurs like Elasmosaurus were specialized fish hunters, using their extended necks to strike at prey with lightning speed. Short-necked varieties like Liopleurodon were apex predators, capable of taking down even large marine reptiles. Their success in aquatic environments shows what was possible when reptiles fully committed to life in the water.

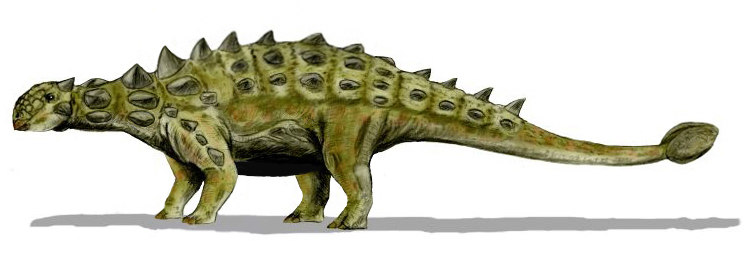

Armored Dinosaurs: Sinking Like Stones

Ankylosaurs and their heavily armored relatives faced significant challenges in aquatic environments. Their thick bony armor, while excellent protection against predators, made them incredibly dense and prone to sinking. These living tanks were built for terrestrial combat, not aquatic adventures.

The club-tailed ankylosaurs would have been particularly disadvantaged in water, as their massive tail weapons would have acted like anchors. Their short, stubby legs were designed for stability on land, not for swimming propulsion. Any ankylosaur that found itself in deep water would likely have faced a dire situation.

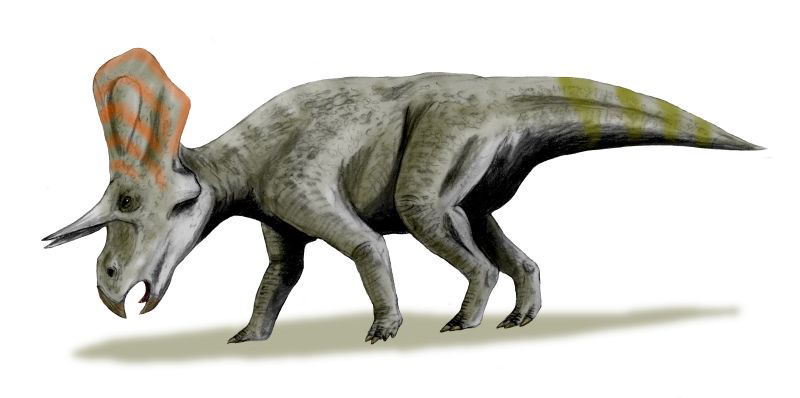

Ceratopsians: Questionable Swimmers

Horned dinosaurs like Triceratops and Styracosaurus were probably poor swimmers due to their massive, heavy skulls and compact bodies. Their enormous frills and horns, while impressive display features, would have created significant drag in water. These herbivores were built for land-based confrontations, not aquatic escapes.

However, some smaller ceratopsians might have been capable of basic swimming when absolutely necessary. Their powerful leg muscles could have provided some propulsion, though their overall body design was far from optimal for aquatic locomotion. River crossings would have been challenging and potentially dangerous endeavors for these heavily-built herbivores.

Pterosaurs: Masters of Multiple Elements

Flying reptiles like pterosaurs had unique advantages when it came to interacting with water. Many species were excellent divers, plunging from great heights to catch fish in ancient seas and lakes. Their lightweight, hollow bones made them naturally buoyant, while their wing membranes could potentially serve as makeshift paddles.

Some pterosaurs, like Pteranodon, likely spent considerable time skimming over water surfaces, snatching fish with their long beaks. Others may have been capable of swimming underwater for short periods, using their wings to propel themselves through the water. Their versatility across air, land, and water made them incredibly successful prehistoric creatures.

Evidence from Fossil Trackways

Fossil trackways provide some of the most compelling evidence for dinosaur swimming behavior. In several locations around the world, paleontologists have discovered tracks that appear to show dinosaurs entering water and beginning to swim. These “swim tracks” show only the tips of claws touching the bottom, suggesting the animals were floating and using their feet for minor propulsion.

The most famous swim tracks come from Texas, where theropod dinosaurs appear to have been swimming across an ancient lake. These trackways show a dramatic change from normal walking gaits to swimming strokes, providing direct evidence of aquatic behavior. Similar tracks have been found in Spain, Australia, and other locations, building a strong case for dinosaur swimming abilities.

Bone Density and Buoyancy Factors

The density of dinosaur bones played a crucial role in their swimming abilities. Species with hollow, air-filled bones had significant advantages in water, as these acted like natural flotation devices. Dense, solid bones, while providing strength and support on land, made swimming much more challenging.

Recent studies have examined the bone density of various dinosaur species to better understand their potential swimming capabilities. Spinosaurus, for example, had unusually dense bones that helped it stay submerged while hunting, contrary to what might be expected. This adaptation shows how different species evolved unique solutions to aquatic challenges.

Tail Morphology and Swimming Efficiency

The shape and structure of dinosaur tails provide important clues about their swimming abilities. Long, laterally compressed tails were ideal for aquatic propulsion, working like natural rudders and propellers. Species with deep, paddle-like tails were almost certainly capable swimmers.

Dinosaurs with club-tailed or heavily armored tails would have faced significant challenges in water. These specialized tail structures, while effective for defense or display, created drag and made swimming nearly impossible. The tail’s function on land often determined whether a dinosaur could effectively navigate aquatic environments.

Modern Comparisons and Behavioral Insights

Studying modern animals provides valuable insights into how dinosaurs might have behaved in water. Large herbivorous mammals like elephants and rhinos are surprisingly good swimmers, despite their massive size. Similarly, many modern birds demonstrate that hollow bones and efficient body design can enable effective swimming.

Crocodiles and other modern reptiles show us how prehistoric creatures might have moved through water. Their powerful tails and streamlined bodies provide excellent models for understanding dinosaur swimming mechanics. Even large predators like tigers and bears are capable swimmers when necessary, suggesting that many theropods could have managed aquatic locomotion.

The Verdict on Prehistoric Swimming

The evidence clearly shows that many dinosaurs were capable swimmers, though their abilities varied dramatically by species and body type. Spinosaurus stands out as the most accomplished aquatic dinosaur, while heavily armored species like ankylosaurs would have struggled in water. Most theropods and many herbivores likely possessed basic swimming abilities that could be used when necessary.

The diversity of dinosaur swimming capabilities reflects the incredible adaptability of these prehistoric creatures. From the fish-hunting Spinosaurus to the river-crossing hadrosaurs, dinosaurs found ways to interact with aquatic environments throughout their evolutionary history. This aquatic versatility may have been one of the keys to their success for over 160 million years.

Understanding dinosaur swimming abilities gives us a more complete picture of these remarkable creatures and their ancient world. Water wasn’t just an obstacle to be avoided—it was another environment to be conquered and utilized. What other surprises about dinosaur behavior might future discoveries reveal?