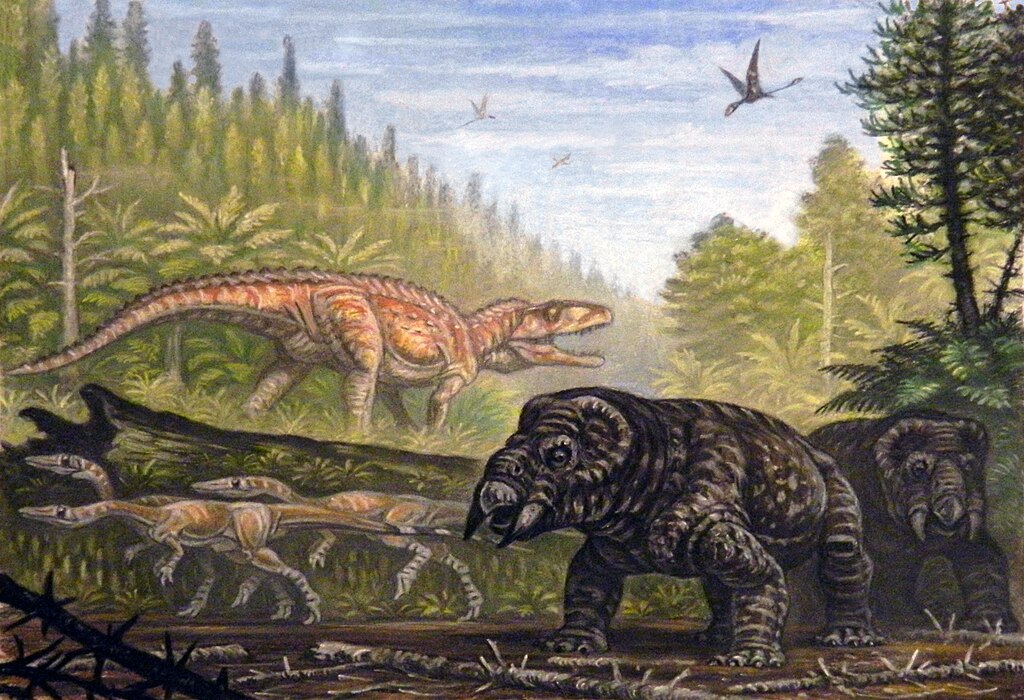

When we think of territorial animals today, wolves patrolling their hunting grounds or lions defending their pride lands immediately come to mind. These modern predators have clear territorial behaviors that we can observe and study. But what about the massive reptiles that ruled Earth millions of years ago? Did dinosaurs, those fascinating creatures from the Mesozoic Era, establish and defend territories like their mammalian counterparts do today? This question has intrigued paleontologists for decades as they piece together the behavioral patterns of animals that vanished 66 million years ago. Through fossil evidence, comparisons with modern relatives, and cutting-edge research techniques, scientists have begun to unravel this mystery, painting an increasingly detailed picture of dinosaur social behavior.

The Challenge of Studying Prehistoric Behavior

Studying the territorial behaviors of animals that went extinct 66 million years ago presents unique challenges for paleontologists. Unlike modern wildlife biologists who can directly observe animal behavior, scientists studying dinosaurs must rely on indirect evidence preserved in the fossil record. Fossils can tell us about an animal’s anatomy, diet, and sometimes cause of death, but behaviors like territoriality leave subtler traces. Scientists must look for clues such as fossil distribution patterns, evidence of combat injuries, anatomical features suited for display or combat, and nesting sites. Additionally, researchers often turn to living dinosaur descendants—birds—and their closest living relatives, crocodilians, to make educated inferences about possible behavioral patterns. This detective work requires cross-disciplinary approaches combining paleontology, ecology, zoology, and comparative anatomy to build reasonable hypotheses about dinosaur social structures.

Evidence from Fossil Distributions

One compelling line of evidence for dinosaur territoriality comes from the distribution patterns of fossil remains. In certain fossil-rich locations, paleontologists have discovered that specific species appear consistently within defined geographical boundaries. For example, studies of Late Cretaceous formations in North America show that certain hadrosaur (duck-billed dinosaur) species maintained discrete ranges that rarely overlapped with closely related species. This pattern suggests these herbivores may have maintained specific territories or home ranges. Similarly, research in the Morrison Formation has revealed that different sauropod species occupied distinct ecological niches within the same general area, potentially indicating territorial separation. These distribution patterns, while not definitive proof of active territorial defense, suggest that different dinosaur populations maintained separate ranges similar to how modern territorial species distribute themselves across landscapes.

Tyrannosaur Territories: The Case for Apex Predator Ranges

Tyrannosaurs, including the famous Tyrannosaurus rex, have provided some of the most compelling evidence for territorial behavior among dinosaurs. Recent studies analyzing the distribution of T. rex fossils suggest these apex predators may have maintained large individual territories spanning hundreds of square miles. Bite marks on tyrannosaur fossils indicating same-species conflict support the hypothesis that these massive predators engaged in territorial disputes. The facial bones of tyrannosaurs show evidence of healed injuries consistent with combat, suggesting confrontations that weren’t immediately fatal. Some paleontologists propose that tyrannosaurs, like modern large predators such as tigers, may have maintained exclusive hunting territories that they actively defended against rivals. This territorial behavior would have been ecologically logical, as each adult T. rex would require vast hunting grounds to sustain its massive body and high energy needs, creating evolutionary pressure to secure and defend resource-rich areas.

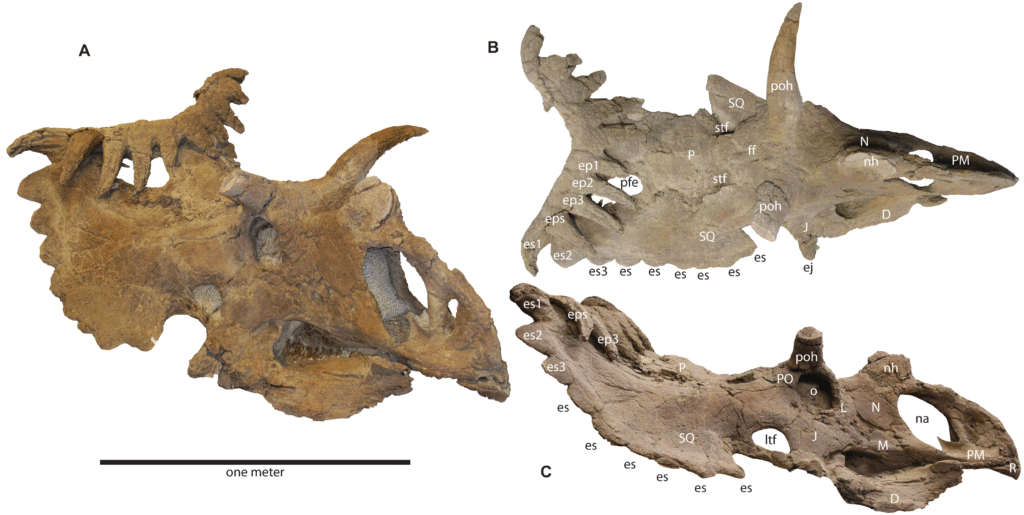

Ceratopsian Display Structures and Territorial Defense

Ceratopsians—the horned dinosaurs including Triceratops and Centrosaurus—possess some of the most elaborate cranial structures in the dinosaur world. Their distinctive frills and horns have long been interpreted as potential weapons for territorial defense. Modern research suggests these elaborate structures likely served multiple purposes, including species recognition, sexual display, and potentially territorial combat. Fossil evidence shows that many ceratopsian specimens bear injuries consistent with intraspecies combat, particularly wounds to the face and frill regions. The discovery of ceratopsian bonebeds, where multiple individuals of the same species died together, indicates these animals lived in herds or groups, which may have collectively defended territories against rival groups. The variation in frill and horn patterns between closely related species also suggests these features played important roles in visual communication and territorial displays, similar to how modern deer use their antlers both for combat and visual signaling.

Nesting Sites as Defended Territories

Perhaps the strongest evidence for dinosaur territoriality comes from nesting sites, which many species appear to have fiercely defended. Remarkable fossil discoveries have revealed that numerous dinosaur species, from small theropods to massive sauropods, returned to the same nesting grounds repeatedly over generations. The famous nesting colonies of Maiasaura in Montana show that these hadrosaurs returned to specific locations year after year to lay eggs and raise their young. Similarly, the nesting grounds of the theropod Troodon and the ceratopsian Protoceratops in Mongolia suggest these animals maintained exclusive breeding territories. In these nesting sites, the spacing between nests often follows predictable patterns that indicate territorial boundaries, similar to modern colonial nesting birds. The dedication to specific nesting locations suggests dinosaurs recognized and defended these areas as critical territories essential for reproductive success, representing a significant investment in territorial behavior.

Pack Hunters and Group Territories

Some dinosaurs appear to have maintained group territories similar to modern wolves or lions. The most compelling evidence comes from dromaeosaurids (the “raptor” dinosaurs) and certain theropods like Allosaurus. Multiple fossil sites have revealed groups of these predators preserved together, suggesting they lived and hunted in coordinated packs. The famous Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry contains numerous Allosaurus specimens of different ages, indicating potential pack behavior. Similarly, sites in Mongolia have revealed Velociraptor specimens in close proximity to each other. These social predators likely maintained group territories that they defended against rival packs, much like modern wolves. Group hunting territories would have provided significant advantages, allowing these dinosaurs to take down prey much larger than themselves through coordination. The social intelligence required for pack hunting and territorial defense suggests these dinosaurs possessed sophisticated behavioral capabilities previously underestimated by researchers.

Hadrosaur Herds and Home Ranges

The abundant fossil record of hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) provides significant insights into potential territorial behaviors among herbivorous dinosaurs. Fossil evidence clearly shows these dinosaurs lived in large herds that could number in the hundreds or even thousands. Modern research suggests these herds likely maintained expansive home ranges rather than strictly defended territories. Analysis of bone beds containing multiple hadrosaur species indicates they migrated seasonally across vast distances, following food resources in patterns similar to modern wildebeest or caribou. Their elaborate head crests, once thought to be primarily for territorial display, are now understood to have served multiple functions including sound production and species recognition. While hadrosaurs may not have defended exclusive territories like predatory dinosaurs, evidence suggests they maintained predictable home ranges to which they returned annually, particularly for breeding purposes, showing a form of site fidelity that represents a more fluid concept of territory than seen in modern territorial mammals.

Ankylosaur and Stegosaur Combat

The heavily armored ankylosaurs and spike-tailed stegosaurs present compelling cases for territorial defense behaviors. Both groups possessed formidable defensive weapons—ankylosaurs with their club-like tails and stegosaurs with their thagomizers (tail spikes)—that could inflict serious damage in combat. Fossil evidence shows injuries consistent with intraspecific fighting, suggesting these weapons weren’t used exclusively against predators but also against rivals, potentially in territorial disputes. Stegosaur thagomizers show wear patterns indicating they were actively used during the animal’s lifetime, not merely displayed as deterrents. Similarly, the tail clubs of ankylosaurs exhibit bone remodeling consistent with repeated impact stress. These armored dinosaurs likely engaged in ritualized combat to establish dominance and territorial rights, similar to how modern rhinoceros or elephant males contest territories. Their relatively slow movement speed and heavy armor suggest they would have defended fixed territories rather than ranging widely, making territorial behavior ecologically advantageous for these distinctive herbivores.

Dinosaur Display Structures and Territorial Signaling

Many dinosaurs possessed elaborate anatomical features that likely served as visual signals for territorial communication. From the sail-backed Spinosaurus to the crest-headed Parasaurolophus, these distinctive structures would have made individuals instantly recognizable at a distance. Modern research suggests these features served multiple purposes, including species recognition, sexual selection, and territorial signaling. The hollow crest of Parasaurolophus, for example, could produce resonant sounds potentially used to announce territorial presence across long distances. Similarly, the elaborate frills of ceratopsians like Styracosaurus may have functioned as visual displays to ward off territorial competitors before physical confrontation became necessary. Even the bright feather displays now known to have adorned many theropod dinosaurs likely served similar signaling purposes. These visual and acoustic signaling adaptations mirror those seen in modern territorial animals like peacocks or howler monkeys, suggesting dinosaurs engaged in complex territorial communication using their specialized anatomical features.

Insights from Modern Birds

As the direct descendants of dinosaurs, modern birds offer crucial insights into potential dinosaur territorial behaviors. Birds display some of the most elaborate territorial behaviors of any animal group, with complex displays, vocalizations, and defense strategies. Many bird species maintain breeding territories they defend vigorously against intruders, particularly during nesting season. The complex courtship displays of birds like sage grouse or birds of paradise likely had parallels in their dinosaur ancestors, particularly among theropods and other feathered dinosaurs. Research has revealed that the brain regions responsible for territorial behavior in modern birds have direct evolutionary connections to similar structures in dinosaur brains. The widespread territoriality among birds across vastly different ecological niches suggests this behavior likely had deep evolutionary roots in their dinosaur ancestors. By studying the territorial behaviors of ground-dwelling birds like ostriches and cassowaries, researchers can make particularly relevant comparisons to non-avian dinosaur behavior patterns.

Comparing Dinosaur Territories to Modern Reptiles

While birds provide one evolutionary perspective on dinosaur behavior, modern reptiles offer another valuable comparison. Many modern reptiles, including crocodilians, monitor lizards, and certain turtles, display territorial behaviors that may parallel those of their distant dinosaur relatives. Alligators and crocodiles, the closest living relatives to dinosaurs besides birds, maintain aquatic territories they defend aggressively, particularly during breeding season. Large monitor lizards establish and patrol territories, with Komodo dragons maintaining home ranges they defend against rivals. The territorial displays of these modern reptiles—including physical confrontations, chemical signaling, and visual displays—may reflect behavioral patterns present in their shared ancestors with dinosaurs. However, important differences exist; reptiles are ectothermic while dinosaurs were likely mesothermic or endothermic, giving dinosaurs potentially greater capacity for active territorial defense. By examining where reptile and bird territorial behaviors overlap, researchers can identify the most likely patterns of territorial behavior that would have existed in their dinosaur relatives.

The Role of Climate and Environment in Dinosaur Territories

The territorial behaviors of dinosaurs were likely heavily influenced by the environments they inhabited and the changing climatic conditions throughout the Mesozoic Era. During the 165 million years dinosaurs dominated Earth, they experienced dramatic climate shifts from the arid Triassic to the lush Jurassic and variable Cretaceous periods. These changing conditions would have altered resource availability and distribution, directly impacting territorial behaviors. In resource-rich environments, territories might have been smaller but more vigorously defended, while harsh environments might have necessitated larger territories or more nomadic lifestyles. The formation of the supercontinent Pangaea and its subsequent breakup created natural geographic boundaries that would have shaped dinosaur territories and potentially led to specialization and unique territorial behaviors in isolated populations. Seasonal variations would have likely influenced territorial behaviors as well, with dinosaurs potentially defending breeding territories during mating seasons but adopting more fluid range patterns during migration or when following food sources. This environmental context is crucial for understanding the ecological pressures that shaped dinosaur territorial strategies.

Future Research Directions

The study of dinosaur territorial behavior continues to evolve as new technologies and methodologies emerge. Advanced isotope analysis of fossil teeth and bones can now reveal migration patterns and habitat usage, providing insights into potential territorial ranges. CT scanning and 3D modeling allow researchers to examine combat injuries and stress patterns on bones that might indicate territorial conflicts. Sophisticated computer modeling can simulate dinosaur movements, sensory capabilities, and population dynamics to test hypotheses about territorial behaviors in virtual environments. Ongoing discoveries of new trackway sites may reveal patterns of movement consistent with territorial patrolling or boundary marking. Additionally, the continuing revolution in our understanding of dinosaur appearance, with new evidence of colors and patterns preserved in exceptionally well-preserved fossils, may provide insights into visual signaling related to territorial displays. As these research techniques advance, our picture of dinosaur territorial behavior will continue to become clearer, potentially revealing complex social structures and behaviors previously unimaginable.

In conclusion, while we may never have the definitive evidence that comes from direct observation, the accumulated fossil record provides compelling support for territorial behaviors among many dinosaur groups. From the predatory tyrannosaurs defending hunting grounds to ceratopsians engaging in ritual combat, and from colonial nesting sites to the pack hunting of dromaeosaurids, dinosaurs appear to have engaged in diverse territorial behaviors adapted to their ecological niches. These behaviors likely ranged from the strict territories of apex predators to the more fluid home ranges of migratory herbivores. By combining fossil evidence with insights from modern relatives and ecological principles, paleontologists continue to develop an increasingly nuanced understanding of how these magnificent animals interacted with each other and their environments. The territorial behaviors of dinosaurs represent just one fascinating aspect of their complex lives that continues to capture scientific and public imagination alike.