For generations, our perception of dinosaurs has been shaped by illustrations, museum displays, and films depicting these ancient creatures lumbering about with their tails dragging behind them. This image became so ingrained in popular culture that it was rarely questioned. However, modern paleontology has dramatically transformed our understanding of how dinosaurs carried themselves, particularly regarding tail posture. The transition from the image of tail-dragging dinosaurs to the more dynamic, tail-aloft dinosaurs we recognize today represents one of the most significant shifts in paleontological thinking. This evolution in our understanding offers fascinating insights into how scientific knowledge develops and how we continually refine our picture of prehistoric life.

The Origins of the Tail-Dragging Dinosaur Image

The notion that dinosaurs dragged their tails originated in the early days of paleontology during the 19th century. Early paleontologists like Richard Owen and Gideon Mantell, working with fragmentary fossils and limited comparative anatomy knowledge, made assumptions based on living reptiles like crocodiles and lizards. These scientists envisioned dinosaurs as essentially oversized lizards, adopting similar postures with sprawling limbs and ground-hugging tails. This interpretation was further cemented by influential paleoartists like Charles R. Knight and Zdeněk Burian, whose dramatic illustrations depicted dinosaurs as ponderous, tail-dragging beasts. Their artwork adorned museum walls and textbooks, effectively establishing this posture as the definitive dinosaur stance in the public imagination for over a century.

Evidence Against Tail-Dragging in the Fossil Record

Contrary to the tail-dragging hypothesis, the fossil record has always contained evidence suggesting a different reality. One of the most compelling pieces of evidence comes from dinosaur trackways, which rarely show tail drag marks despite preserving detailed foot impressions. If dinosaurs habitually dragged their tails, we would expect to see continuous furrows between footprints, yet such marks are notably absent in the vast majority of trackways. Additionally, the structure of tail vertebrae in many dinosaur species reveals specialized features that would have made the tail relatively rigid and held horizontally. The presence of ossified tendons that run along the vertebrae in many dinosaur tails would have created a semi-rigid structure that functioned more as a counterbalance than a drag-behind appendage. These anatomical features strongly indicate that tail-dragging was not the norm among dinosaurs.

The Biomechanical Revolution in Dinosaur Studies

The shift in our understanding of dinosaur posture gained significant momentum in the 1960s and 1970s with the work of paleontologists like John Ostrom and Robert Bakker, who championed a more active, dynamic view of dinosaurs. Through detailed biomechanical analysis, these scientists demonstrated that dinosaurs were not simply oversized reptiles but represented a distinct and highly successful group with unique adaptations. They calculated center of mass, examined muscle attachment sites, and analyzed joint mobility to show that most dinosaurs would have held their tails horizontally as counterbalances to their forward body weight. This biomechanical approach revealed that tail-dragging would have been energetically inefficient and inconsistent with the physical capabilities of these animals. The elevated tail posture also aligned with evidence suggesting that many dinosaurs were active, warm-blooded animals rather than the sluggish, cold-blooded creatures previously imagined.

The “Dinosaur Renaissance” and Changing Perceptions

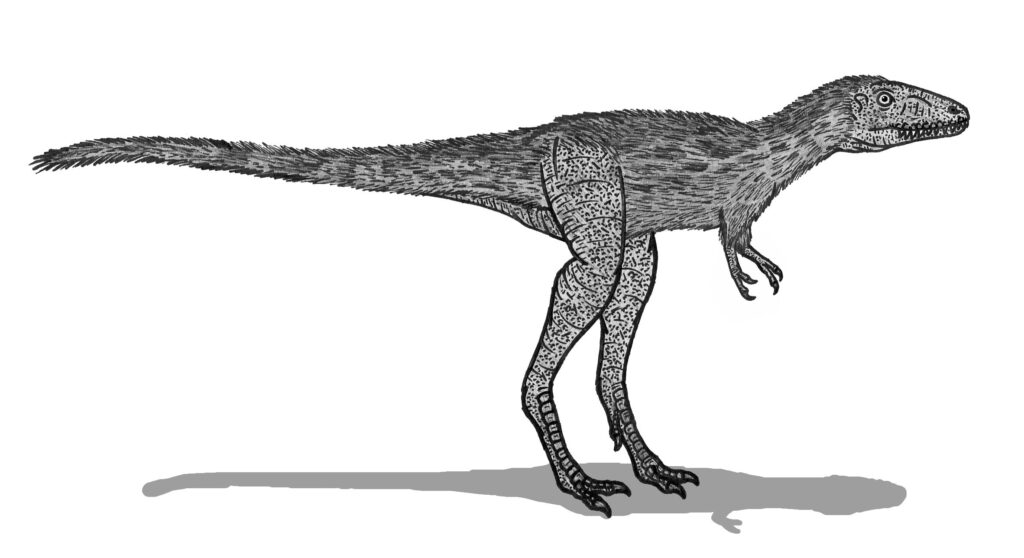

The dramatic shift in how we visualize dinosaurs, including tail posture, was part of a broader scientific revolution often referred to as the “Dinosaur Renaissance.” This period, spanning roughly from the late 1960s through the 1980s, completely transformed our understanding of dinosaur biology, behavior, and appearance. Led by paleontologists like John Ostrom, who discovered the remarkably bird-like Deinonychus, scientists began reconsidering virtually every aspect of dinosaur life. The image of dinosaurs evolved from slow, plodding reptiles to active, possibly warm-blooded animals that held their bodies and tails off the ground. This revolution wasn’t just about tail posture—it encompassed questions about metabolism, social behavior, parental care, and the evolutionary relationship between dinosaurs and birds. The horizontal tail became symbolic of this broader shift toward seeing dinosaurs as sophisticated, successful animals rather than evolutionary dead ends.

Why Tails Were Held Aloft: Form and Function

Dinosaur tails served multiple crucial functions that would have been compromised by dragging. For bipedal dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus and Velociraptor, the tail acted as a dynamic counterbalance to the head and torso, enabling efficient bipedal locomotion. The substantial mass of muscle and bone in these tails created a counterweight that balanced the front-heavy body around the hip joint, much like a tightrope walker’s pole. For quadrupedal dinosaurs such as Diplodocus and Stegosaurus, the tail similarly helped distribute body weight and may have served additional purposes. Some species had specialized tail weapons like the thagomizer spikes of Stegosaurus or the club of Ankylosaurus, which would have been most effective when held off the ground. Additionally, tails may have played roles in social display, species recognition, and possibly even thermoregulation in some dinosaur groups. None of these functions would be well-served by a tail that dragged along the ground.

Tail Adaptations Across Different Dinosaur Groups

Dinosaur tails exhibited remarkable diversity, reflecting the varied ecological roles these animals played. Theropods—the bipedal, primarily carnivorous dinosaurs including Tyrannosaurus and the ancestors of birds—typically had relatively stiff tails reinforced with bony projections called zygapophyses that limited flexibility and created an effective counterbalance. Sauropods, the massive long-necked herbivores, possessed incredibly long, whip-like tails that may have been used for defense or social signaling. Some sauropod tails featured specialized vertebrae that could potentially create a whip-crack effect when moved rapidly. Ornithischians, the “bird-hipped” dinosaurs including Stegosaurus and Triceratops, often had tails adapted for specific defensive purposes. The ceratopsians generally had shorter tails while thyreophoran dinosaurs like ankylosaurs developed elaborate tail clubs or spikes. In each case, the tail adaptations reflected specific evolutionary pressures and functions that required an elevated, not dragging, posture.

Exceptions to the Rule: When Tails Might Have Touched Ground

While the evidence overwhelmingly indicates that most dinosaurs held their tails aloft during normal locomotion, there were likely situations when tails did contact the ground. During rest periods, some dinosaurs might have lowered their tails to the ground to conserve energy, much as many modern birds do when not in motion. Certain species with particularly massive or lengthy tails, like some of the larger sauropods, might have allowed the distal portions of their tails to touch the ground occasionally. Some tail drag marks have been found in the fossil record, though they appear to be relatively rare and may represent unusual circumstances such as injured animals, unusual substrates, or specific behaviors rather than normal locomotion. Young or juvenile dinosaurs might also have had different tail postures compared to adults as their musculature and balance developed. These exceptions, however, only highlight the rule that habitual tail-dragging was not the norm for most dinosaur species.

How Modern Birds Inform Our Understanding

Modern birds, as the living descendants of theropod dinosaurs, provide valuable insights into dinosaur posture and movement. Birds typically hold their reduced tails off the ground, using them for balance, steering during flight, and display. While modern birds have much shorter tails than their dinosaur ancestors, the fundamental biomechanical principles remain similar. The caudofemoralis muscle, which connects the tail to the thigh in birds and was much larger in non-avian dinosaurs, plays a crucial role in locomotion and necessitates an elevated tail position. Studies of ground-dwelling birds like ostriches and emus, which rely more on their legs than wings, show how these animals use their tails for balance during running—a function that would have been even more important for their dinosaur ancestors. The continuous evolutionary line from dinosaurs to birds strongly supports the interpretation that non-avian dinosaurs, especially theropods, held their tails horizontally rather than dragging them.

Famous Tail-Draggers in Popular Culture

Despite scientific evidence to the contrary, the image of tail-dragging dinosaurs persisted stubbornly in popular culture throughout much of the 20th century. The 1933 film “King Kong” featured dinosaurs with dragging tails, establishing a visual precedent that influenced generations of monster movies. The 1940 Disney film “Fantasia,” while groundbreaking in many ways, depicted dinosaurs including Tyrannosaurus and Stegosaurus with their tails sweeping the ground. Even the original “Jurassic Park” film from 1993, though revolutionary in many aspects of dinosaur portrayal, included some scenes where dinosaur tails touched the ground more than modern paleontology would suggest. Children’s books, toys, and museum displays continued to perpetuate the tail-dragging image well into the late 20th century, demonstrating the lag time between scientific understanding and popular representation. These cultural depictions, while scientifically outdated, remain important artifacts in the history of how we have visualized prehistoric life.

The Role of Computer Modeling in Posture Studies

Modern technology has revolutionized how paleontologists study dinosaur posture, particularly through sophisticated computer modeling techniques. Using CT scans of fossils, scientists can create detailed digital models of dinosaur skeletons, complete with accurate joint surfaces and proportions. These digital models allow researchers to test range of motion, calculate center of mass, and simulate different postures to determine which configurations would have been physically possible and biomechanically efficient. Software programs can model muscle systems based on attachment points visible on fossils and comparisons with living relatives, providing insights into how dinosaurs moved and balanced. Some studies even incorporate finite element analysis, a technique borrowed from engineering, to test how different tail postures would have affected stress distribution throughout the skeleton during various activities. These computational approaches have consistently supported the tail-aloft hypothesis while providing increasingly detailed understanding of the specific mechanics involved for different dinosaur species.

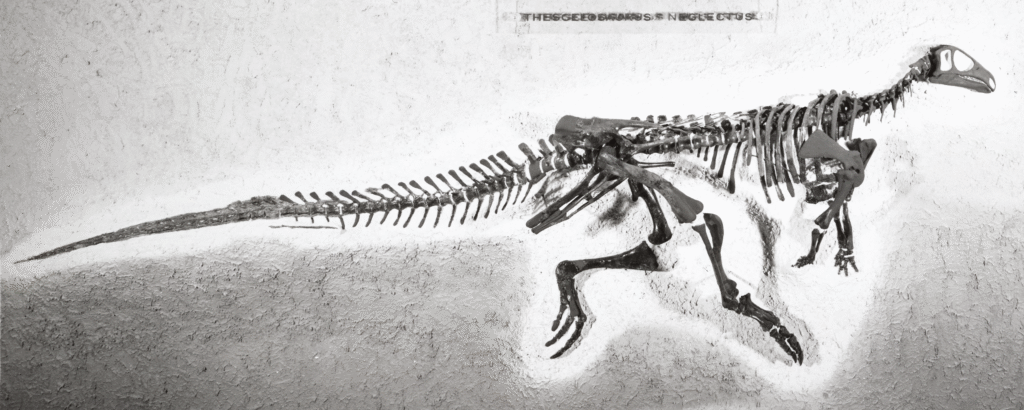

Evolution of Museum Displays: From Dragging to Dynamic

Museum displays of dinosaur skeletons offer a visible chronicle of how scientific understanding of dinosaur posture has evolved over time. Early mounted skeletons from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such as the famous Diplodocus carnegii installations funded by Andrew Carnegie, typically showed dinosaurs in a sprawling, tail-dragging pose. As understanding advanced, museums began updating their displays, often dramatically. The American Museum of Natural History’s renovation of its dinosaur halls in the 1990s featured newly posed skeletons with horizontal tails and more dynamic postures. London’s Natural History Museum similarly transformed its iconic Diplodocus display, “Dippy,” from a tail-dragger to a more active pose before eventually replacing it with a blue whale skeleton. These museum renovations not only reflect scientific progress but also serve as powerful educational tools, allowing the public to literally see how our understanding has changed. Modern museums now routinely display dinosaurs in active poses with elevated tails, sometimes even showing movement or behavior, reflecting the current scientific consensus.

Persistence of the Tail-Dragging Myth

Despite decades of scientific evidence supporting elevated tail postures, the image of tail-dragging dinosaurs continues to persist in some contexts. This persistence illustrates the challenge of updating deeply entrenched public perceptions about prehistoric life. Outdated dinosaur illustrations continue to be reproduced in some educational materials, particularly those with limited budgets for new artwork. Some toy manufacturers still produce dinosaur figures with dragging tails, either due to manufacturing constraints or adherence to traditional designs. The power of nostalgia also plays a role, as adults may unconsciously prefer dinosaur representations that match what they grew up with. Cultural inertia means that scientific understanding often takes decades to fully permeate popular awareness. This lag between scientific consensus and public perception serves as a fascinating case study in how scientific knowledge is communicated and how visual representations can sometimes impede rather than advance accurate understanding of the natural world.

Implications for Our Understanding of Dinosaur Behavior

The shift from viewing dinosaurs as tail-draggers to recognizing them as animals with dynamically balanced tails has profound implications for how we understand their behavior and capabilities. With properly balanced, horizontal tails, many dinosaurs would have been capable of much greater speed and agility than previously thought. Theropod dinosaurs like Velociraptor, freed from the drag and instability of a ground-trailing tail, emerge as nimble, efficient predators capable of quick direction changes and sustained pursuit. Social behaviors also take on new dimensions when we recognize dinosaurs as more active creatures; elevated tails could have served as visual signals during courtship displays or territorial confrontations. Parental care becomes more plausible in the context of more agile, energetic animals. Even feeding strategies must be reconsidered—bipedal dinosaurs with horizontal tails could maintain better balance while tackling prey or reaching for high vegetation. The tail-aloft perspective has cascading effects throughout our reconstruction of dinosaur lives, contributing to the modern view of these animals as dynamic, successful organisms rather than evolutionary oddities.

Lessons from the Tail-Dragging Paradigm Shift

The transition from viewing dinosaurs as tail-draggers to understanding them as tail-lifters offers valuable lessons about the nature of scientific progress. This shift reminds us that science is self-correcting, with new evidence and analysis constantly refining or sometimes completely overturning previous conceptions. The persistence of the tail-dragging image despite contrary evidence demonstrates how initial scientific interpretations, especially when widely visualized, can become entrenched and difficult to dislodge from both scientific and public thinking. This case highlights the importance of questioning assumptions, particularly when they’re based on limited evidence or inappropriate analogies to modern animals. It also illustrates how multiple lines of evidence—from fossil trackways to biomechanical analysis to comparative anatomy—converge to provide more accurate understanding. Perhaps most importantly, the tail-dragging story demonstrates the vital importance of updating public-facing science communication, as outdated images can perpetuate misconceptions for generations. This paradigm shift stands as a powerful example of how scientific understanding evolves and improves over time.

Conclusion

The notion that dinosaurs dragged their tails represents one of paleontology’s most persistent and widely corrected misconceptions. From the fossil evidence of trackways lacking tail marks to the biomechanical impossibility of efficient movement with a dragging tail, multiple lines of evidence have thoroughly debunked this once-common depiction. Modern understanding recognizes dinosaur tails as dynamic structures held aloft to serve crucial functions in balance, locomotion, defense, and possibly communication. This transformation in our perception of dinosaur posture exemplifies the self-correcting nature of science and reminds us that our understanding of prehistoric life continues to evolve. As we move forward, we can expect further refinements in how we envision dinosaurs, but the tail-dragging dinosaur has been firmly relegated to the history of science rather than the history of dinosaurs themselves.