When we think of the Mesozoic Era, most of us imagine a world dominated by towering dinosaurs, with our mammalian ancestors scurrying underfoot, hiding in the shadows. This traditional narrative portrays early mammals as small, timid creatures that posed no threat to their reptilian counterparts. However, recent paleontological discoveries in North America have begun to challenge this conventional wisdom, suggesting a more complex relationship between early mammals and dinosaurs. Fossil evidence increasingly indicates that some mammals may have been more aggressive than previously thought, potentially even hunting smaller dinosaurs. This fascinating possibility reshapes our understanding of prehistoric ecosystems and the evolutionary dynamics that unfolded millions of years ago.

The Traditional View of Early Mammals

For decades, the scientific consensus portrayed early mammals as diminutive creatures, rarely exceeding the size of modern shrews or mice. These small, primarily nocturnal animals were thought to have survived in the dinosaur-dominated world by exploiting ecological niches that larger reptiles couldn’t access. Most paleontologists believed early mammals fed primarily on insects, seeds, and occasionally small vertebrates like lizards or amphibians. Their small size and presumed nocturnal habits were considered adaptations that helped them avoid predation by dinosaurs rather than compete with them directly. This narrative fit neatly with the fossil record available at the time, which consisted mainly of teeth and jaw fragments indicating small body sizes and insectivorous diets.

Redefining Mesozoic Mammals: New Discoveries

The discovery of remarkably complete mammal fossils from the Mesozoic Era has significantly altered our understanding of early mammalian ecology. Spectacular finds in North American formations, particularly in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, the Kaiparowits Formation of Utah, and the Dinosaur Park Formation in Alberta, have revealed mammals with more diverse morphologies than previously recognized. Some of these mammals, like Repenomamus from Asia (though not North American), were substantially larger than traditionally thought possible for Mesozoic mammals, reaching the size of modern badgers. These discoveries have forced paleontologists to reconsider the ecological roles these animals might have played. Complete skeletons, rather than isolated teeth, have revealed adaptations for various lifestyles, including some features suggesting predatory behavior that could have made certain dinosaurs potential prey.

The Fossil Evidence for Mammal-Dinosaur Conflict

Several key fossil discoveries provide tantalizing evidence for direct interactions between mammals and dinosaurs. Perhaps most compelling are the stomach contents of certain mammal fossils, which occasionally include dinosaur remains. One famous example comes from China, where a Repenomamus specimen was found with the remains of a young Psittacosaurus dinosaur in its abdominal region. While this specific example isn’t from North America, similar evidence has begun to emerge from North American formations. Tooth marks on small dinosaur bones that match the dental patterns of contemporary mammals provide indirect evidence of predation. Additionally, coprolites (fossilized feces) attributed to mammals sometimes contain dinosaur bone fragments, suggesting that at least some mammals included dinosaurs in their diet, even if only as scavenged remains rather than hunted prey.

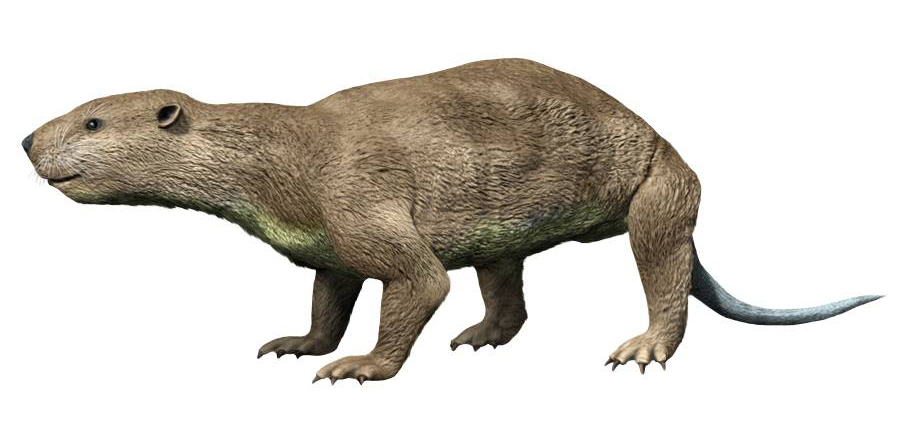

Multituberculates: The Successful Mammalian Order

Among the most successful mammalian groups in Late Cretaceous North America were the multituberculates, rodent-like mammals with distinctive molars bearing multiple cusps or “tubercles.” These creatures thrived for over 100 million years, making them one of the most successful mammal lineages in Earth’s history. Recent research suggests that some multituberculates grew considerably larger than previously thought, with certain species potentially reaching the size of modern beavers. Their complex dentition indicates adaptability in diet, potentially including plant material, insects, and possibly small vertebrates. Some multituberculate species show adaptations suggesting they were active predators, with powerful jaws and specialized teeth that could have been used to dispatch prey, potentially including hatchling or juvenile dinosaurs. Their long evolutionary success suggests they were skilled at exploiting resources in dinosaur-dominated ecosystems.

Metatherians and Eutherians: Ancestors of Modern Mammals

The Late Cretaceous period in North America witnessed the diversification of two mammalian groups that would eventually give rise to modern mammals: metatherians (marsupial ancestors) and eutherians (placental mammal ancestors). Fossil evidence from formations like Hell Creek reveals that these groups included some species with carnivorous adaptations. Their teeth show features associated with slicing meat, and some specimens had proportionally larger bodies than previously recognized for Mesozoic mammals. Deltatheridium, a metatherian found in North America, possessed dental characteristics suggesting it was an active predator capable of tackling prey larger than insects. These mammals were likely opportunistic predators that could have occasionally preyed on small dinosaurs, particularly vulnerable hatchlings, when the opportunity presented itself. Their ability to adapt to various prey types may have contributed to their survival through the end-Cretaceous extinction event.

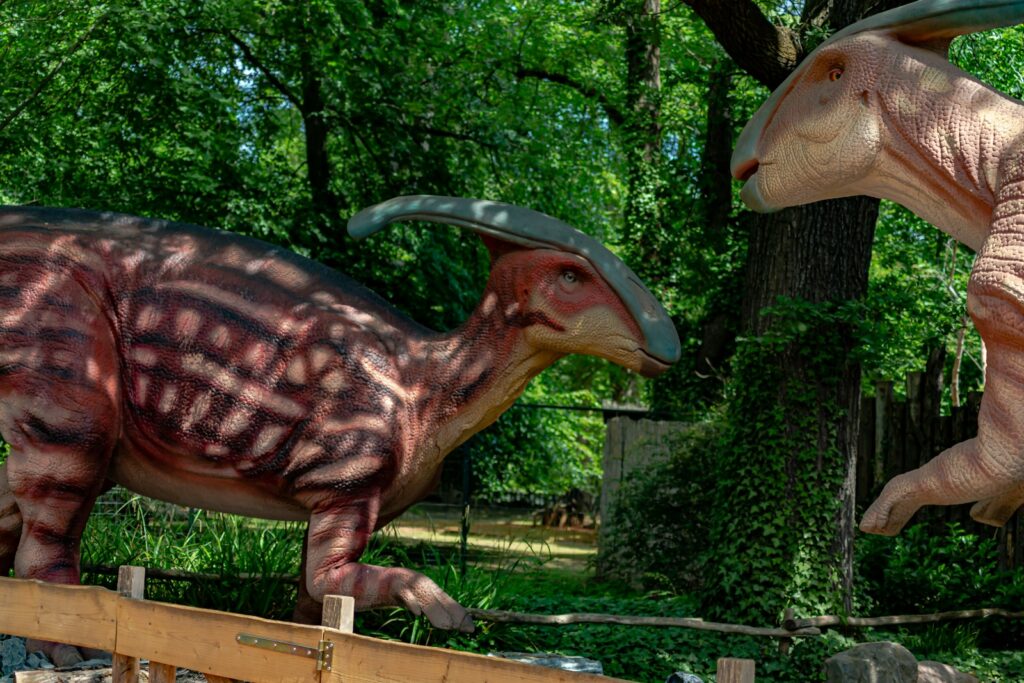

Small Dinosaurs as Potential Prey

When considering which dinosaurs might have been vulnerable to mammalian predation, the focus naturally falls on the smallest dinosaur species and juveniles of larger species. North America during the Late Cretaceous was home to numerous small dinosaur species, including diminutive ornithopods, primitive birds, and juvenile specimens of various dinosaur groups. Some of these animals were similar in size to modern lizards or small birds, making them potential prey for larger Mesozoic mammals. Particularly vulnerable would have been nesting sites, where eggs and newly hatched dinosaurs presented easy targets for opportunistic mammalian predators. Recent discoveries of dinosaur nesting grounds in formations like Two Medicine in Montana show evidence of predation, and while traditionally attributed to other dinosaurs, some of this predation may have come from mammals.

Specialized Hunting Adaptations in Mesozoic Mammals

Close examination of Mesozoic mammal fossils from North American formations reveals adaptations consistent with predatory behavior. Some species possessed enlarged canines and carnassial-like teeth for slicing through flesh, features associated with carnivorous diets in modern mammals. Limb proportions in certain specimens suggest the ability to pursue prey or climb, potentially to access nests. Cranial features indicating enhanced sensory capabilities, such as large brain cases with regions devoted to smell and hearing, would have aided in hunting activities, especially for nocturnal predators. Some North American mammals from the Late Cretaceous, like Didelphodon, had powerful jaws with bone-crushing capabilities that could have been used to overcome small vertebrate prey. These anatomical features collectively support the hypothesis that some mammals possessed the physical equipment necessary to hunt small dinosaurs.

The Ecological Context of Mammal-Dinosaur Interactions

Understanding the broader ecological context is crucial when evaluating the likelihood of mammals hunting dinosaurs. Late Cretaceous North America featured diverse ecosystems ranging from coastal plains to upland forests, creating numerous ecological niches where mammals and dinosaurs intersected. The prevalence of nocturnal adaptations in Mesozoic mammals suggests they may have been active when many dinosaurs were less active, providing hunting opportunities with reduced risk. Seasonal factors also likely played a role, as periods of dinosaur nesting would have created temporary abundance of vulnerable prey. Resource competition between mammals and small dinosaurs may have occasionally escalated to predation when opportunities arose. Evidence of coevolutionary adaptations, where both groups show features suggesting responses to pressure from the other, further supports the idea of meaningful ecological interactions between these animal groups.

Scientific Debates and Alternative Interpretations

The hypothesis that Mesozoic mammals hunted dinosaurs remains controversial within paleontological circles, with researchers offering various interpretations of the available evidence. Some scientists argue that apparent predation marks could represent scavenging behavior rather than active hunting, noting that many modern small carnivores are primarily scavengers when it comes to larger prey. Others question whether mammalian jaw strength and dental adaptations were sufficient for subduing even small dinosaurs, suggesting that evidence of dinosaur remains in mammal diets may represent exceptional rather than typical behavior. Taphonomic issues—processes affecting how organisms become fossilized—further complicate interpretations, as spatial association of mammal and dinosaur remains doesn’t necessarily indicate predation. The limited fossil record, representing only a tiny fraction of ancient life, means we must be cautious about generalizing from the few preserved instances of apparent interaction between these groups.

Technological Advancements Revealing New Evidence

Modern technological approaches have revolutionized our ability to detect and interpret evidence of mammal-dinosaur interactions. Micro-CT scanning allows researchers to examine the internal structure of fossils without damaging them, revealing hidden details of tooth wear patterns and stomach contents that may indicate predatory behavior. Isotopic analysis of teeth provides insights into ancient food webs by tracking the flow of carbon and nitrogen through ecosystems, potentially revealing trophic relationships between mammals and dinosaurs. New microscopy techniques have enabled identification of tooth marks on bones with unprecedented precision, allowing researchers to attribute marks to specific animal groups with greater confidence. Ancient DNA and molecular studies, while still limited for Mesozoic specimens, offer tantalizing possibilities for understanding predator-prey relationships in the distant past. These technological advances continue to uncover evidence that would have been impossible to detect using traditional paleontological methods.

Geographic Variations in Mammal-Dinosaur Interactions

Evidence for mammal predation on dinosaurs appears to vary geographically across North America, suggesting that ecological relationships differed based on regional conditions. The Hell Creek Formation of Montana and the Dakotas has yielded some of the most compelling evidence for mammalian carnivory, including specimens of Didelphodon with adaptations suggesting predatory behavior. The Lance Formation of Wyoming shows different patterns of mammal diversity, with species showing more specialized dentition potentially related to different dietary niches. Coastal formations like those in New Jersey present evidence of marine-influenced ecosystems where mammals and dinosaurs interacted differently than in inland habitats. High-latitude fossil sites in Alaska reveal mammal communities adapted to more seasonal conditions, potentially with different predatory strategies than their southern counterparts. These geographic variations remind us that mammal-dinosaur interactions were not uniform but shaped by local environmental conditions and evolutionary histories.

Implications for Understanding Evolutionary Dynamics

The possibility that mammals hunted dinosaurs has profound implications for our understanding of evolutionary dynamics during the Mesozoic Era. Traditional narratives portraying mammals as ecologically suppressed by dinosaurs until after the end-Cretaceous extinction event may require significant revision if mammals were actively influencing dinosaur populations through predation. Evidence of predatory relationships suggests a more complex interplay of selective pressures, with mammals potentially driving evolutionary adaptations in small dinosaurs, such as improved parental care or defensive features. The evolutionary arms race between predator and prey may have accelerated diversification in both groups, contributing to the remarkable diversity of both mammals and dinosaurs by the Late Cretaceous. Recognizing mammals as active participants rather than passive bystanders in Mesozoic ecosystems enriches our understanding of the evolutionary forces that shaped both groups and ultimately influenced which lineages survived the end-Cretaceous extinction event.

Future Research Directions

Paleontologists continue to pursue multiple avenues of research to better understand potential mammal-dinosaur predatory relationships. Targeted excavations in formations known for preserving exceptional specimens are ongoing, with researchers specifically looking for evidence of direct interactions such as stomach contents or bite marks. Comparative studies of modern predator-prey relationships provide models for interpreting ancient evidence, particularly regarding size differentials between predators and their prey. Biomechanical analyses using computer modeling help assess the predatory capabilities of Mesozoic mammals by estimating bite forces and predicting how their teeth and jaws would have functioned. Investigation of nesting sites remains a priority, as these locations would have been prime targets for mammalian predation. Integration of multiple lines of evidence from paleontology, ecology, and evolutionary biology promises to provide a more comprehensive picture of these ancient interactions, potentially revealing that mammals played a more significant role in Mesozoic food webs than traditionally recognized.

Conclusion

The emerging evidence suggesting that some Mesozoic mammals may have hunted dinosaurs challenges our long-held perceptions of prehistoric ecosystems. While the idea remains controversial and requires further research, fossil discoveries from North American formations provide tantalizing clues that mammals were not merely passive inhabitants of dinosaur-dominated landscapes but active participants capable of influencing dinosaur populations. From specialized dental adaptations to stomach contents containing dinosaur remains, multiple lines of evidence hint at a more complex relationship between these animal groups. As paleontological techniques continue to advance, we may uncover more definitive evidence of these ancient predator-prey relationships. What becomes increasingly clear is that the Mesozoic world was not simply a “dinosaur era” where mammals waited in the wings, but a complex ecosystem where diverse animals interacted in sophisticated ways, each shaping the evolutionary trajectory of the other.