The Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County houses one of the most impressive dinosaur collections in the world. Its renowned Dinosaur Hall, reimagined and reopened in 2011 after extensive renovations, spans two vast gallery spaces totaling 14,000 square feet. This paleontological paradise showcases more than 300 real fossils, 20 complete dinosaur skeletons, and numerous interactive exhibits that bring the Mesozoic Era to vibrant life. The hall represents not just a display of ancient bones but a carefully crafted scientific narrative about evolution, adaptation, and the dynamic nature of life on Earth. Visitors of all ages find themselves transported back millions of years, walking among giants that once ruled our planet, while learning about cutting-edge paleontological discoveries and techniques.

The Dramatic Entrance: Meeting the T. rex Trio

Visitors entering the Dinosaur Hall are immediately greeted by one of its most spectacular displays: three Tyrannosaurus rex specimens arranged in a growth sequence. This remarkable exhibit features a baby, juvenile, and adult T. rex positioned in lifelike poses that suggest movement and interaction. The adult specimen, known as Thomas, is one of the most complete T. rex skeletons ever discovered, with approximately 85% of its original bones intact. The growth series dramatically illustrates how these fearsome predators developed from relatively small juveniles into massive adults, gaining about five pounds per day during their peak growth years. Perhaps most fascinating is how the exhibit reveals changes in bone structure and proportions throughout the life cycle, showing that young T. rex individuals were more lightly built and likely faster than their massive adult counterparts.

The Mamenchisaurus: A Neck Above the Rest

Dominating the central space of the hall is the awe-inspiring Mamenchisaurus, a sauropod dinosaur known for having the longest neck of any known dinosaur. The specimen on display stretches an impressive 68 feet from head to tail, with its neck alone accounting for nearly half that length. This remarkable adaptation allowed Mamenchisaurus to reach high vegetation without moving its massive body, conserving energy while feeding efficiently in the Jurassic forests of what is now China. The museum’s specimen is mounted in a dynamic pose with its neck extended upward, demonstrating how these creatures might have accessed food sources unavailable to other herbivores. Visitors can walk directly underneath this gentle giant, gaining a unique perspective on its scale and anatomical features that paleontologists have studied to understand how such an elongated neck could function without collapsing under its weight.

The Allosaurus Growth Series: Life and Death in the Jurassic

One of the most scientifically significant exhibits in the hall features multiple Allosaurus specimens that tell a compelling story of life, injury, and death in the Jurassic period. The centerpiece is a nearly complete adult Allosaurus with clear evidence of numerous injuries and infections that it survived, including broken ribs, a damaged shoulder blade, and infected jaw bones. Paleontologists have nicknamed this resilient individual “Big Al,” and its fossils provide valuable insights into dinosaur healing processes and immune responses. Alongside this battle-scarred veteran are younger Allosaurus specimens that help scientists understand growth patterns in these predatory dinosaurs. The exhibit includes detailed explanations of how researchers can determine the age of dinosaurs by examining growth rings in their bones, similar to the way tree rings record annual growth. This collection represents one of the most comprehensive growth series for any large theropod dinosaur in any museum worldwide.

The Triceratops Discovery: From Field to Museum

The museum’s magnificent Triceratops display tells the compelling story of paleontological fieldwork and museum preparation. This specimen, affectionately named “Hank,” was discovered in Montana in 2010 and includes about 70% of the original skeleton, making it one of the most complete Triceratops ever found. What makes this exhibit particularly special is its presentation, which shows portions of the fossil exactly as they were discovered in the field, still partially embedded in the original matrix rock. Adjacent sections display fully prepared bones, creating a before-and-after effect that educates visitors about the painstaking process of fossil extraction and preparation. Interactive screens accompany the exhibit, featuring time-lapse videos of the actual excavation and laboratory work, allowing visitors to appreciate the years of careful scientific work required to bring a dinosaur from discovery to display. The specimen’s famous three-horned skull, measuring over seven feet in length, demonstrates why Triceratops remains one of the most recognizable dinosaurs in popular culture.

Thomas the T. rex: A Scientific Treasure

The crown jewel of the museum’s collection is undoubtedly Thomas the T. rex, one of the ten most complete Tyrannosaurus rex specimens ever discovered. Excavated from the Hell Creek Formation in Montana, Thomas lived approximately 66-68 million years ago during the late Cretaceous period, just before the mass extinction event that wiped out non-avian dinosaurs. What makes Thomas particularly valuable to science is the exceptional preservation of certain rarely found elements, including gastralia (belly ribs) and a complete furcula (wishbone), which provide important clues about T. rex anatomy and its evolutionary relationship to birds. The specimen is mounted in an active, hunting pose with its massive skull turned slightly, jaws open to reveal its iconic serrated teeth that could crush bone with a bite force estimated at over 12,000 pounds per square inch. Museum scientists have conducted extensive research on Thomas, including detailed CT scans of the skull that have revealed previously unknown aspects of sensory abilities and brain structure in these apex predators.

Dinosaur Trackways: Footprints from the Past

Beyond skeletal remains, the Dinosaur Hall features remarkably preserved trackways that capture prehistoric moments frozen in time. These trace fossils include a series of sauropod footprints from the Morrison Formation, showing the walking pattern of these massive creatures as they moved across what was once a muddy shoreline. Each footprint measures over three feet in diameter and reveals details about the animal’s weight, speed, and even aspects of its soft tissue anatomy that aren’t preserved in bones. Alongside these are theropod tracks that demonstrate the distinctive three-toed footprint pattern that links dinosaurs to their modern bird descendants. The museum presents these trackways with interactive lighting that alternately highlights different sets of prints, helping visitors distinguish between multiple dinosaur species that traversed the same ancient landscape. Perhaps most captivating is a rare instance of predator-prey interaction preserved in stone – a series of tracks showing what appears to be a pursuit, with the spacing between footprints suddenly widening to indicate acceleration as one dinosaur fled from another.

The Preparation Lab: Science in Action

A distinctive feature of the Dinosaur Hall is its working paleontology preparation laboratory, where visitors can observe museum scientists and trained volunteers performing the delicate work of cleaning and preserving newly discovered fossils. This glass-enclosed lab space brings the behind-the-scenes work of the museum directly into public view, with specialists using tools ranging from dental picks and small pneumatic chisels to microscopes and chemical hardeners to carefully free fossils from surrounding rock. The lab is equipped with video screens and intercoms that allow visitors to ask questions directly to the preparators about their current projects and techniques. Scheduled demonstrations throughout the day showcase specific preparation challenges, such as how scientists safely remove the mineral matrix surrounding delicate fossils without damaging the specimen. This transparent approach to museum work helps visitors understand that paleontology is an active, ongoing science rather than a static collection of old bones, and many young visitors cite this exhibit as their inspiration for pursuing careers in paleontology or related sciences.

Interactive Learning Stations: Hands-On Paleontology

Throughout the Dinosaur Hall, carefully designed interactive stations transform visitors from passive observers into active participants in paleontological discovery. These hands-on exhibits include a fossil dig pit where younger visitors can uncover replica dinosaur bones buried in sand, learning excavation techniques used by real paleontologists in the field. Another popular station allows visitors to manipulate dinosaur joint replicas to understand how scientists determine how these animals moved and what range of motion was possible in different limbs. Touch screens offer virtual dissections of dinosaur anatomy, revealing internal structures and comparing them to modern animals to highlight evolutionary connections. Perhaps the most engaging interactive feature is the “Be a Paleontologist” station, where visitors can work through an actual case study of a fossil discovery, making scientific decisions at each step from identification to classification, experiencing firsthand how paleontologists conclude from incomplete evidence. These interactive elements are strategically placed throughout the hall, breaking up the viewing of static displays and catering to different learning styles while reinforcing key scientific concepts.

The Hall’s Scientific Impact: Research Contributions

Beyond its role as a public exhibition space, the Dinosaur Hall functions as an active research center that has contributed significantly to paleontological knowledge. The museum’s vertebrate paleontology collection includes over 35 million specimens, many of which are studied by researchers from around the world. Several major scientific papers have resulted from work on the hall’s specimens, including groundbreaking research on dinosaur growth rates based on the Allosaurus and T. rex growth series on display. The museum’s paleontology department maintains active field programs that continue to discover new specimens, some of which are periodically added to the hall’s displays after study and preparation. The institution has pioneered new techniques in fossil preparation and conservation, developing methods now used by museums worldwide. Perhaps most significantly, the hall’s specimens have been instrumental in research exploring the dinosaur-bird transition, with several fossils showing feather impressions and other avian characteristics that help document this evolutionary connection. This dual function as both a public exhibition and a scientific research collection represents the museum’s commitment to advancing knowledge while making science accessible to everyone.

Ancient Ecosystems: Dinosaurs in Context

Rather than presenting dinosaurs as isolated specimens, the Dinosaur Hall places them within the context of their ancient ecosystems through detailed environmental reconstructions. These dioramas and informational displays help visitors understand what the world was like when dinosaurs roamed, featuring plants, insects, and smaller vertebrates that shared their habitats. One particularly effective display recreates a section of late Cretaceous forest with a T. rex moving through vegetation that existed during that period, including ancient relatives of ginkgo trees and cycads that survive today as “living fossils.” The exhibit explains how paleobotanists determine what plants existed in dinosaur environments by studying fossil pollen and plant remains found in the same rock layers as dinosaur bones. Climate information derived from geological evidence helps complete the picture, showing that many dinosaurs lived in environments quite different from their modern geographic locations. These contextual displays are crucial for understanding dinosaur adaptations, as features like crests, plates, and specialized teeth only make evolutionary sense when considered within the environment and ecological relationships for which they evolved.

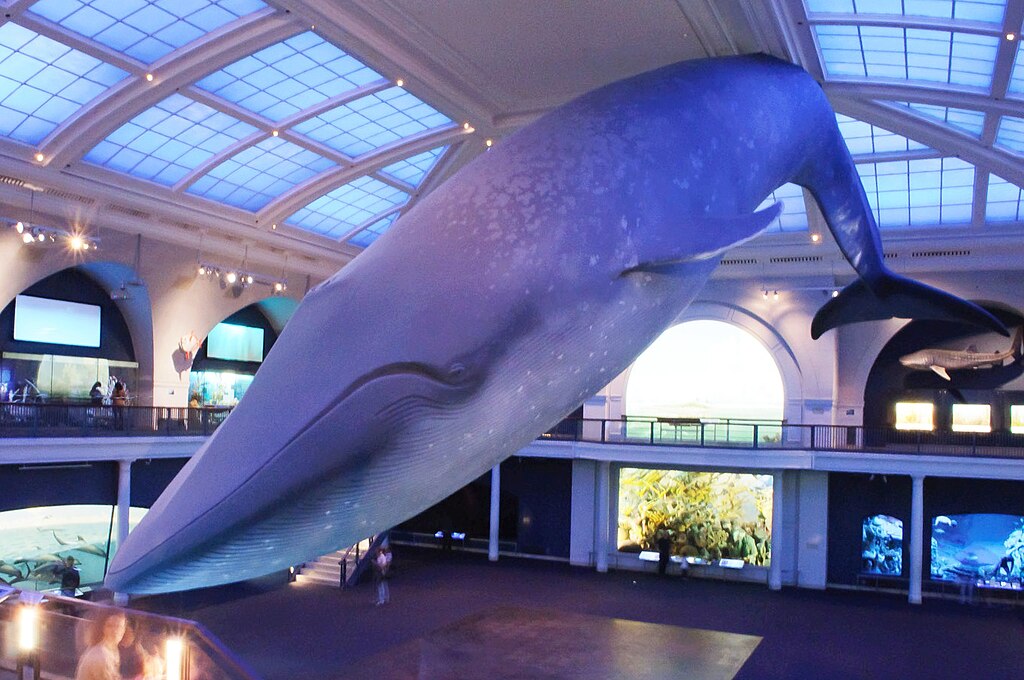

Beyond Dinosaurs: The Marine Reptile Gallery

Complementing the terrestrial dinosaur exhibits, the hall includes a spectacular section dedicated to the marine reptiles that dominated Earth’s oceans during the Mesozoic Era. This collection features several complete plesiosaur and mosasaur skeletons suspended from the ceiling as if swimming through ancient seas, including a 42-foot-long Tylosaurus (a type of mosasaur) discovered in Kansas when that region was covered by a vast inland sea. Unlike dinosaurs, these marine reptiles were not dinosaurs but rather distinct reptilian lineages that returned to aquatic environments, evolving flippers from limbs and developing streamlined bodies for efficient swimming. The exhibit highlights the convergent evolution between these ancient marine reptiles and modern marine mammals like whales and dolphins, which independently evolved similar body shapes in response to the hydrodynamic demands of marine life despite being separated by millions of years. Interactive displays allow visitors to explore the hunting strategies and sensory adaptations of these predators, including evidence that some species possessed specialized organs for detecting electrical fields generated by prey animals hidden in murky water or ocean floor sediments.

The Art of Dinosaur Reconstruction

An innovative aspect of the Dinosaur Hall is its transparent approach to showing visitors how paleontologists and artists collaborate to create accurate reconstructions of extinct animals. Throughout the exhibition, displays contrast what is directly known from fossils with what must be inferred through scientific reasoning and comparative anatomy. Skeletal mounts are accompanied by illustrations showing multiple possible interpretations of the living animal’s appearance, with explanations of the evidence supporting each version. One fascinating display shows the evolution of Tyrannosaurus rex reconstructions over the past century, from the upright, tail-dragging postures of early 20th-century museums to the more horizontal, dynamic poses supported by current scientific understanding. The exhibit also addresses ongoing scientific debates, such as whether certain dinosaurs had feathers or scales, presenting the evidence for different viewpoints rather than presenting a single “correct” answer. This approach gives visitors insight into the scientific process itself, showing that paleontology, like all sciences, constantly refines its understanding as new evidence emerges and analytical techniques improve.

The Future of Paleontology: New Technologies on Display

The Dinosaur Hall showcases cutting-edge technologies that are revolutionizing paleontological research and our understanding of prehistoric life. Interactive displays demonstrate how CT scanning and 3D printing allow scientists to study internal structures of fossils without damaging them, and to create perfect replicas for research and exhibition. Visitors can explore digital reconstructions of dinosaur brains based on endocasts (natural casts of brain cavities), which provide insights into sensory capabilities and behaviors of extinct species. The hall features examples of molecular paleontology, where advanced chemical techniques have allowed scientists to identify preserved proteins and pigment cells from dinosaur fossils, helping determine their actual coloration and providing biochemical evidence of their evolutionary relationship to birds. Perhaps most impressive is the visualization theater, where large-scale projections demonstrate how paleontologists use computer modeling to test hypotheses about dinosaur movement, calculating muscle forces and joint stress to determine how these animals moved and behaved. These technological exhibits not only educate about dinosaurs themselves but inspire younger visitors by showing the interdisciplinary nature of modern paleontology, which incorporates physics, chemistry, engineering, and computer science alongside traditional fossil study.

Conclusion

The Dinosaur Hall at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County stands as one of the premier paleontological exhibitions in the world, balancing scientific rigor with accessibility and wonder. Through its thoughtfully designed displays, interactive elements, and commitment to showcasing both established knowledge and ongoing research, the hall offers something meaningful for visitors of all ages and levels of scientific background. Beyond simply presenting impressive fossils, it tells the story of life’s evolution and adaptation across millions of years, connecting visitors to Earth’s deep history and the scientific methods that reveal it. As paleontology continues to advance with discoveries and technologies, the Dinosaur Hall evolves as well, ensuring that this remarkable space will continue to educate and inspire generations of future scientists and dinosaur enthusiasts for decades to come.