Edmontonia, a remarkable armored dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous period, roamed the landscapes of what is now North America approximately 76 to 65 million years ago. This formidable herbivore belonged to the nodosaurid family, a group of heavily armored dinosaurs that relied on passive defense rather than active combat. With its distinctive array of spikes, scutes, and armored plates, Edmontonia represents one of nature’s most impressive defensive adaptations. Its fossil remains, discovered primarily in Alberta, Canada, and the western United States, have provided paleontologists with valuable insights into the diversity of armored dinosaurs and their evolutionary strategies for survival in ecosystems dominated by fearsome predators like Tyrannosaurus rex.

Discovery and Naming of Edmontonia

The first fossils of Edmontonia were discovered in the early 20th century in the Edmonton Formation of Alberta, Canada, which ultimately inspired the dinosaur’s name. The genus was formally named and described by paleontologist Charles Mortram Sternberg in 1928, based on a well-preserved skeleton. The type species, Edmontonia longiceps, translates roughly to “long-headed Edmonton creature,” referencing both its geographic origin and one of its distinctive features.

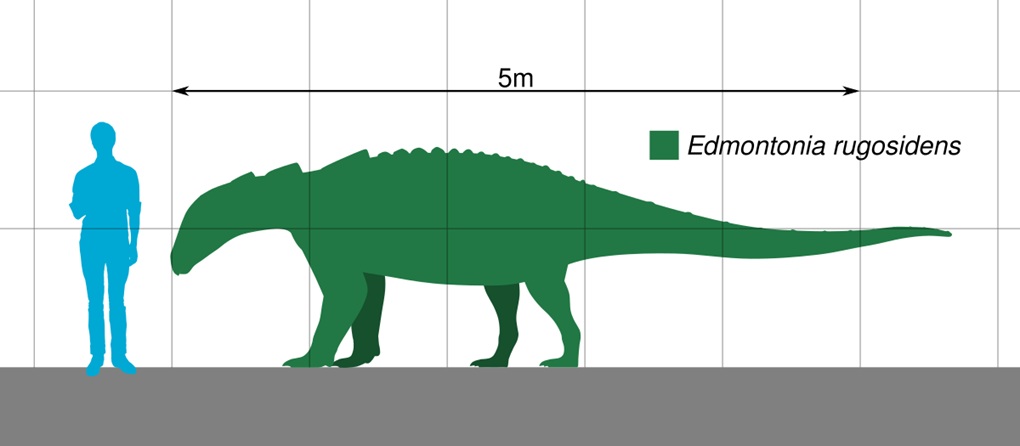

A second species, Edmontonia rugosidens, was identified later and is distinguished by slight variations in its armor pattern and skull structure. Throughout the decades following its initial discovery, additional specimens have been unearthed across western North America, providing scientists with a more complete understanding of this armored dinosaur’s anatomy and helping to distinguish it from related nodosaurids.

Physical Characteristics and Size

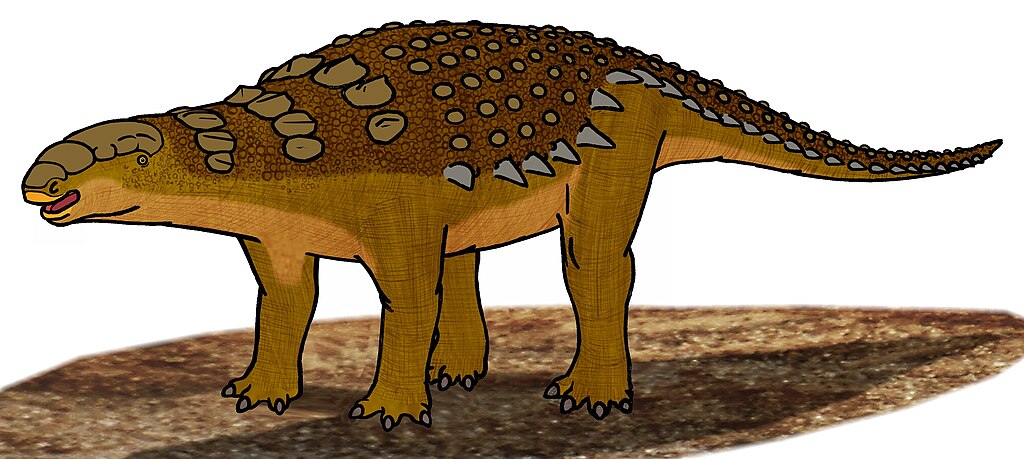

Edmontonia was a medium-sized nodosaurid that typically measured about 6 to 7 meters (20 to 23 feet) in length and stood approximately 2 meters (6.5 feet) tall at the shoulder. Despite its relatively modest dimensions compared to giants like Brachiosaurus, this armored dinosaur was quite hefty, with weight estimates ranging from 3 to 4 tons. Its body was low-slung and tank-like, with short, sturdy limbs positioned beneath a wide torso.

The skull of Edmontonia was elongated and somewhat triangular when viewed from above, featuring a narrow snout that widened toward the rear. Like other nodosaurids, it had a relatively small brain case but possessed keen senses of smell and hearing, crucial adaptations for detecting approaching predators in its prehistoric environment. The overall body shape of Edmontonia reflected its specialized lifestyle as a slow-moving herbivore that relied on armor rather than speed for protection.

Defensive Armor and Weaponry

The most striking feature of Edmontonia was undoubtedly its elaborate defensive armor, which covered nearly the entire dorsal surface of its body from neck to tail. This armor consisted of hundreds of bony plates called osteoderms embedded in the skin, forming a natural chainmail that protected vital organs from predator attacks. Unlike its ankylosaur relatives, Edmontonia lacked a tail club but compensated with large, sharp shoulder spikes that projected outward and slightly forward from each shoulder.

These impressive spikes, some reaching over 30 centimeters (12 inches) in length, would have presented a formidable deterrent to any predator considering an attack from the side or front. The arrangement of armor also included smaller spines and knobs along the flanks and specialized, flattened plates that created a continuous protective shield over the neck and back. This defensive system made Edmontonia one of the most well-protected herbivores of its time, capable of withstanding attacks from even the largest theropod predators.

Taxonomic Classification and Relatives

Edmontonia belongs to the family Nodosauridae, which together with the Ankylosauridae makes up the larger group Ankylosauria—the armored dinosaurs. Nodosaurids are distinguished from ankylosaurids by their lack of tail clubs and somewhat narrower bodies. Close relatives of Edmontonia include other nodosaurids such as Panoplosaurus, Sauropelta, and Borealopelta, with which it shares many anatomical features. The nodosaurid family first appeared in the Middle Jurassic period and survived until the end of the Cretaceous, making them a remarkably successful group with a duration of over 100 million years.

Within this family tree, Edmontonia represents one of the more derived (advanced) forms, displaying specialized adaptations that evolved over millions of years of natural selection. Recent phylogenetic analyses suggest that Edmontonia shared a common ancestor with Panoplosaurus, with both genera representing a specialized North American branch of the nodosaurid family that thrived during the Late Cretaceous period.

Habitat and Geographic Distribution

Edmontonia fossils have been discovered primarily in western North America, with significant finds in the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, as well as in the western United States, particularly Montana and Wyoming. During the Late Cretaceous period, these regions were part of an ancient landmass known as Laramidia, which was separated from eastern North America by the Western Interior Seaway, a vast inland sea. The environment Edmontonia inhabited was a coastal plain characterized by river systems, forests, and open woodlands with a seasonal climate that was warmer and more humid than today’s.

This diverse landscape provided abundant vegetation for herbivores like Edmontonia to feed upon. Different species and specimens of Edmontonia have been found in slightly different geological formations, suggesting that this genus existed across various microhabitats and survived through several million years of ecological changes before the mass extinction event that ended the Mesozoic era.

Diet and Feeding Habits

As a nodosaurid dinosaur, Edmontonia was an obligate herbivore with a diet consisting primarily of low-growing vegetation. Its narrow snout and leaf-shaped teeth were specialized for selective feeding rather than the bulk grazing seen in some other herbivorous dinosaurs. The teeth of Edmontonia were relatively small and featured a simple design suited for slicing through fibrous plant material, which was then processed in its large gut. Analysis of fossil teeth and jaw mechanics suggests that Edmontonia likely fed on ferns, cycads, conifers, and early flowering plants that made up the understory of Late Cretaceous forests.

Some paleontologists have proposed that the low-slung posture and narrow snout allowed these dinosaurs to selectively browse on particular plants or plant parts, possibly targeting more nutritious items like fruits, seeds, or young shoots. Digestive efficiency would have been crucial for Edmontonia, as the high-fiber, relatively low-nutrient plant material of the Cretaceous required extended processing times to extract sufficient energy.

Movement and Locomotion

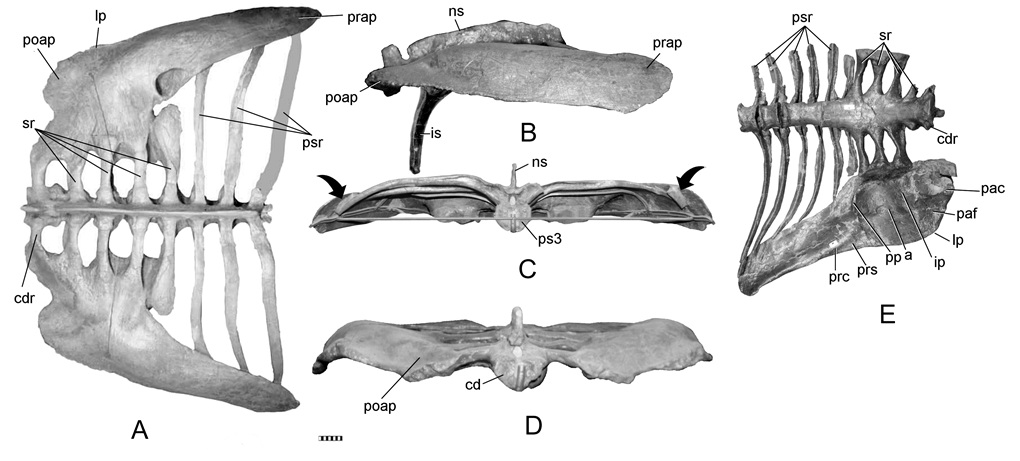

The locomotion of Edmontonia was characterized by a slow, deliberate gait resulting from its heavy armor and quadrupedal stance. Its limbs were positioned more directly under the body than in earlier dinosaurs, providing better support for its considerable weight. Skeletal analysis reveals that Edmontonia had relatively short but powerful limbs with broad feet that would have distributed its weight effectively over soft ground. The shoulder girdle and hip structure were robust, anchoring strong muscles that powered its movements despite the burden of heavy armor.

Studies of limb proportions and joint articulation suggest that Edmontonia was capable of sustained walking at slow speeds but probably couldn’t move quickly or maneuver rapidly when threatened. Instead of fleeing from predators, Edmontonia would have relied on its defensive armor and intimidating shoulder spikes, potentially adopting a stationary defensive posture when confronted by threats. This locomotor strategy reflects an evolutionary trade-off, sacrificing speed and agility for the protection offered by heavy armor.

Social Behavior and Lifestyle

While direct evidence of social behavior in extinct animals is difficult to establish conclusively, paleontologists can make reasonable inferences based on fossil evidence and comparisons with modern animals. In the case of Edmontonia, the discovery of multiple individuals in certain fossil beds suggests that these armored dinosaurs may have occasionally gathered in small groups, possibly for protection or while exploiting abundant food resources. However, there’s no compelling evidence for complex social structures or herding behavior as seen in some other dinosaur groups.

The lifestyle of Edmontonia was likely that of a solitary or loosely gregarious animal that spent most of its time foraging for plants across its woodland habitat. Given its formidable defensive capabilities, adult Edmontonia would have had few natural predators to fear, potentially allowing for a relatively unhurried existence focused on meeting its considerable nutritional needs. The lack of obvious sexual dimorphism in discovered specimens makes it difficult to determine whether males and females had different social roles or behaviors.

Predator-Prey Relationships

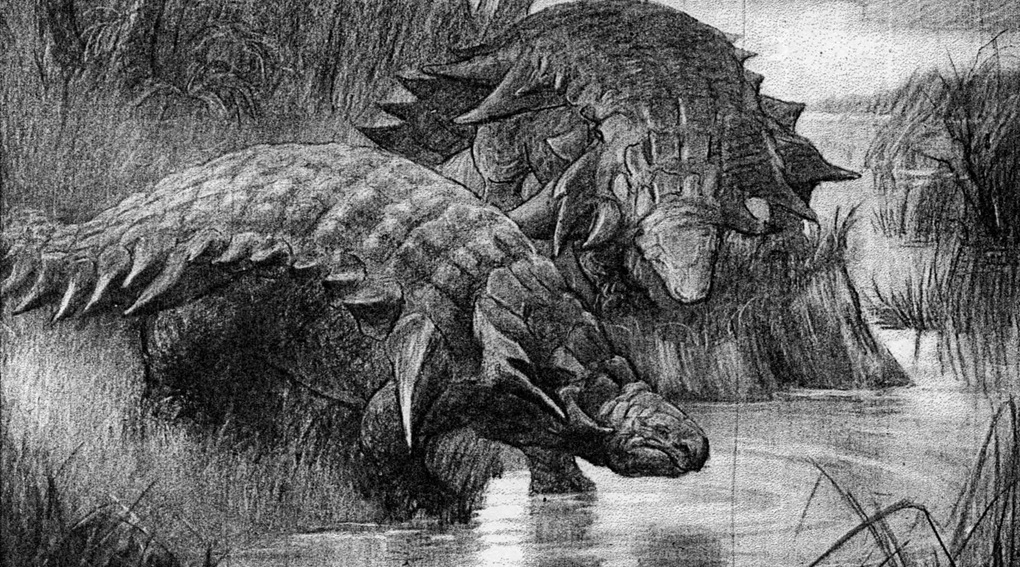

Despite its impressive array of defensive features, Edmontonia coexisted with some of the most fearsome predators in Earth’s history, including tyrannosaurs such as Albertosaurus and, later, Tyrannosaurus rex. These large theropods possessed powerful jaws capable of delivering crushing bites, but would have found the heavily armored Edmontonia a challenging target. When threatened, Edmontonia likely adopted a defensive stance, lowering its body to the ground and positioning itself to present its armored side and threatening shoulder spikes toward the attacker.

Young or sick individuals would have been more vulnerable to predation, but healthy adult Edmontonia probably enjoyed relative safety from all but the most determined predators. Intriguingly, some Edmontonia fossils show evidence of healed injuries, suggesting that these animals sometimes survived predatory attacks or other traumatic events. The evolutionary arms race between increasingly powerful predators and the enhanced defensive capabilities of animals like Edmontonia represents one of the classic examples of coevolution in the dinosaur ecosystem.

Growth and Development

The growth pattern of Edmontonia, like that of many dinosaurs, involved substantial changes from hatchling to adult. Young Edmontonia would have been more vulnerable than adults, lacking the fully developed armor that characterized mature individuals. Studies of bone microstructure in nodosaurids suggest that these dinosaurs experienced relatively rapid growth in their early years before slowing as they approached adult size. The development of the distinctive armor would have occurred progressively throughout youth, with the full complement of defensive plates and spikes only present in mature specimens.

Paleontologists estimate that Edmontonia may have reached sexual maturity before attaining full adult size, a pattern common in many reptiles. The growth rings observed in cross-sections of Edmontonia bones indicate seasonal variations in growth rate, suggesting that these dinosaurs’ development was influenced by environmental factors such as food availability throughout the year. Complete growth from hatchling to adult size likely took at least a decade, representing a substantial investment in development before reaching the relative safety afforded by full armor.

Scientific Significance and Major Discoveries

Edmontonia holds special significance in paleontology as one of the best-represented nodosaurid dinosaurs, with multiple specimens providing insights into the diversity and specialization of armored dinosaurs. One of the most important discoveries was the nearly complete specimen described by Sternberg in 1928, which established many of the defining characteristics of the genus. In recent decades, advanced techniques such as CT scanning and 3D modeling have allowed scientists to better understand the arrangement of armor and internal anatomy of Edmontonia without damaging precious fossils.

Particularly significant are studies comparing Edmontonia to the exceptionally preserved nodosaurid Borealopelta, which retained soft tissue impressions and skin, providing insights into how the armor of related dinosaurs like Edmontonia may have appeared in life. The continuing discovery of Edmontonia material helps scientists reconstruct the paleobiogeography of Late Cretaceous North America, showing how different dinosaur species were distributed across ancient landscapes and ecological niches.

Edmontonia in Popular Culture

While not as famous as dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus or Triceratops, Edmontonia has appeared in various educational programs, books, and exhibits focused on prehistoric life. Its distinctive appearance, with impressive shoulder spikes and extensive body armor, makes it a visually striking subject for paleoartists and museum displays. Edmontonia has been featured in several documentary series about dinosaurs, where its defensive capabilities are often highlighted as an example of evolutionary adaptation.

In museum settings, Edmontonia reconstructions demonstrate the diversity of dinosaur body plans and defensive strategies, offering visitors a glimpse of alternatives to the “horns and frills” defense made famous by ceratopsians. Several major natural history museums around the world display Edmontonia fossils or replicas, including the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Alberta, Canada, which houses significant specimens from the region where many Edmontonia fossils have been discovered. Though less frequently merchandised than some other dinosaurs, Edmontonia appears in educational toy lines and detailed models aimed at dinosaur enthusiasts and collectors.

Extinction and Legacy

Edmontonia, like all non-avian dinosaurs, perished in the mass extinction event at the end of the Cretaceous period approximately 66 million years ago. This catastrophic event, triggered by an asteroid impact and compounded by massive volcanic activity, dramatically altered Earth’s climate and ecosystems, resulting in the disappearance of roughly 75% of all species on the planet. Despite their formidable defenses against predators, nodosaurids like Edmontonia could not survive the global environmental collapse that followed.

The disappearance of Edmontonia and its relatives marked the end of the nodosaurid lineage, though their distant cousins—birds—would continue the dinosaur legacy into the modern era. The evolutionary innovations displayed by Edmontonia, particularly its elaborate defensive armor, represent a fascinating chapter in vertebrate evolution and demonstrate the remarkable diversity of adaptations that emerged during the Mesozoic Era. Today, the study of Edmontonia continues to yield insights into dinosaur biology, ecology, and the complex dynamics of prehistoric ecosystems that shaped life on Earth for millions of years.

Conclusion

Edmontonia represents one of nature’s most impressive defensive specialists, an armored dinosaur whose evolutionary strategy prioritized protection over speed or offensive capabilities. Its elaborate array of armor plates and intimidating shoulder spikes made it a challenging target for even the largest predators of the Late Cretaceous.

Though Edmontonia and its nodosaurid relatives ultimately perished in the mass extinction that claimed all non-avian dinosaurs, their fossil remains provide valuable insights into prehistoric ecosystems and evolutionary adaptations. As paleontological techniques continue to advance, our understanding of these remarkable armored dinosaurs grows ever more detailed, allowing us to better appreciate the diverse pathways that evolution has taken throughout Earth’s long history.