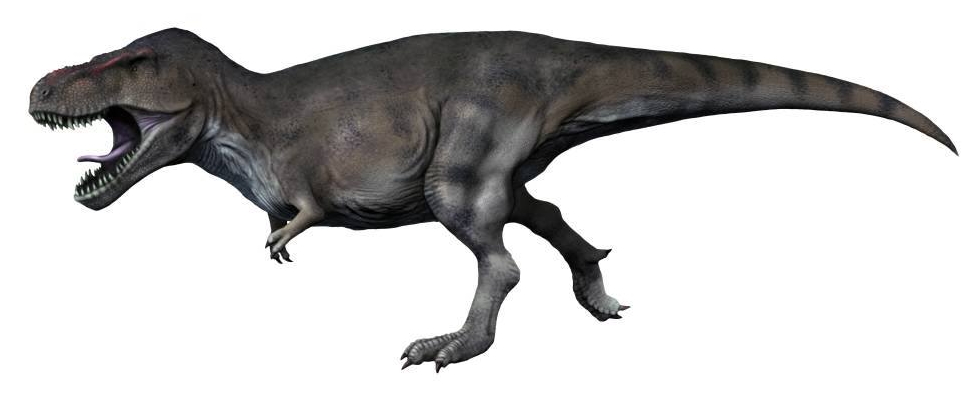

For generations, our collective imagination has pictured Tyrannosaurus rex as a terrifying, scaly predator stomping through prehistoric landscapes. However, recent paleontological discoveries have challenged this long-held image, suggesting that the king of dinosaurs might have sported feathers rather than scales, at least partially. This possibility has ignited fierce debate among scientists and dinosaur enthusiasts alike. What does the fossil evidence tell us about T. rex’s appearance? Were these apex predators covered in plumage like modern birds, or is the truth more nuanced? Let’s explore what the fossils are saying about feathers on T. rex and how our understanding of these magnificent creatures continues to evolve.

The Evolution of Dinosaur Imagery

Our perception of dinosaurs has undergone dramatic transformations since the first fossils were scientifically described in the early 19th century. Initially portrayed as slow, lumbering reptiles with dragging tails, dinosaurs were reimagined in the “Dinosaur Renaissance” of the 1960s and 1970s as more active, warm-blooded creatures. The discovery of Deinonychus, a swift, agile predator with possible feather coverings, began to shift scientific thinking. By the 1990s, evidence from China’s Liaoning Province revealed exquisitely preserved feathered dinosaur fossils, establishing the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and modern birds beyond doubt. These discoveries forced a complete rethinking of dinosaur appearance, behavior, and physiology that continues to this day, with traditional scaly depictions increasingly giving way to feathered reconstructions even for larger species.

The Dinosaur-Bird Connection

The evolutionary relationship between dinosaurs and birds represents one of paleontology’s most fascinating stories. Modern birds are not merely related to dinosaurs—they are dinosaurs, specifically the surviving members of a group called theropods that includes Velociraptor and T. rex. This connection, first proposed by Thomas Henry Huxley in the 1860s based on anatomical similarities between Archaeopteryx and small dinosaurs, faced resistance until overwhelming evidence accumulated in the late 20th century. The discovery of dozens of feathered non-avian dinosaur species in China’s Liaoning Province provided direct evidence of this relationship. These fossils revealed a clear evolutionary progression from simple filamentous structures to complex flight feathers, demonstrating that many features once thought unique to birds—including feathers, wishbones, and air-filled bones—evolved in their dinosaurian ancestors long before the capacity for flight.

Types of Feathered Dinosaurs Already Confirmed

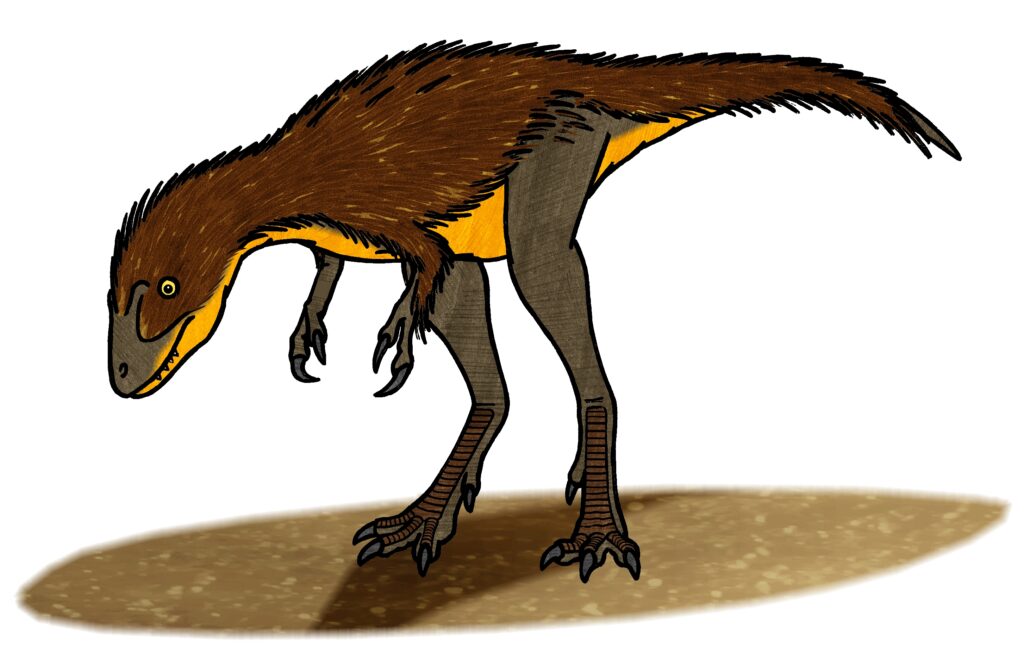

The fossil record has yielded an impressive array of confirmed feathered dinosaurs, primarily from exquisitely preserved specimens found in China, Mongolia, and Germany. Small, raptor-like dinosaurs such as Microraptor displayed fully developed pennaceous feathers on all four limbs, suggesting they could glide between trees. The turkey-sized Sinosauropteryx revealed simple filamentous proto-feathers covering its body, representing an early stage in feather evolution. Perhaps most surprising was the discovery of large tyrannosauroids like Yutyrannus huali, a 30-foot relative of T. rex that displayed extensive feather coverings despite its substantial size. Other notable examples include Caudipteryx, with its fan-shaped tail feathers; Anchiornis, whose fossil impressions allowed scientists to determine its actual coloration; and Dilong, a small tyrannosaur with filamentous coverings. These findings confirm that feathers were widespread among theropod dinosaurs and evolved long before they were used for flight.

The Tyrannosaurid Family Tree

Tyrannosaurus rex belongs to the tyrannosaurid family, a group of large theropod dinosaurs that dominated the Northern Hemisphere during the Late Cretaceous period. This family evolved from much smaller ancestors, with early tyrannosauroids like Dilong and Guanlong measuring just a fraction of T. rex’s imposing size. These earlier, smaller relatives have been found with preserved feather impressions, establishing that the tyrannosauroid lineage inherited feathers from its theropod ancestors. The tyrannosaurid family underwent significant changes as it evolved, including dramatic increases in size, proportionally smaller forelimbs, and more powerful jaws. While most attention focuses on T. rex, the family includes other impressive members like Albertosaurus, Daspletosaurus, and Tarbosaurus, each with their specialized adaptations. Understanding this evolutionary context is crucial for evaluating whether T. rex itself retained feathers or lost them as an adaptation to its massive size.

Yutyrannus: The Game-Changing Discovery

The 2012 discovery of Yutyrannus huali (meaning “beautiful feathered tyrant”) revolutionized our understanding of large tyrannosauroids. This 30-foot, 1.5-ton predator from Early Cretaceous China (about 125 million years ago) preserved clear evidence of long, filamentous feather structures across multiple parts of its body. As the largest definitively feathered dinosaur yet discovered, Yutyrannus challenged the prevailing hypothesis that large dinosaurs would have shed feathery coverings due to the risk of overheating. The feathers on Yutyrannus were simple filaments rather than the complex flight feathers of birds, suggesting they functioned primarily for insulation or display rather than locomotion. Though Yutyrannus lived about 60 million years before T. rex and belonged to a different branch of the tyrannosaur family tree, its substantial size demonstrated that even multi-ton predatory dinosaurs could benefit from feather coverings, reopening the question of T. rex’s appearance.

Direct Evidence: What T. rex Skin Impressions Tell Us

When evaluating whether T. rex had feathers, the most compelling evidence comes from actual T. rex skin impressions that have been discovered. These rare specimens, including impressions from the neck, pelvis, and tail regions, consistently show pebbly, scaly skin similar to that of modern reptiles rather than feather attachment sites. A particularly significant find published in 2017 described multiple T. rex skin patches that preserved scaly integument. These findings suggest that at least some portions of T. rex were covered in scales rather than feathers. However, these impressions represent only small sections of the dinosaur’s total body surface, leaving open the possibility that feathers might have been present on other parts not represented in the fossil record. The patchy nature of skin preservation means these findings establish the presence of scales in certain areas but cannot definitively rule out feathers elsewhere on the body.

The Size Factor: Thermoregulation Challenges

A critical consideration in the T. rex feather debate involves the physics of heat regulation in giant animals. At roughly 40 feet long and weighing up to 9 tons, adult T. rex faced fundamentally different thermoregulation challenges than smaller dinosaurs. Large animals retain heat more efficiently due to their lower surface-area-to-volume ratio, potentially making extensive insulation problematic rather than beneficial. Modern elephants and rhinoceroses evolved sparse hair coverings for this very reason, despite descending from furry ancestors. T. rex lived in a warm Cretaceous climate, further reducing the need for insulation that feathers would provide. This thermoregulation principle, known as Bergmann’s rule, suggests that adult T. rex might have shed most feathers to avoid overheating, particularly in warm environments. However, the same principle suggests that juvenile T. rex, being much smaller, might have retained a more extensive feather covering until reaching larger sizes.

Developmental Considerations: Baby T. rex vs. Adult T. rex

The possibility of ontogenetic changes—differences between juvenile and adult forms—offers a compelling hypothesis in the T. rex feather debate. Young T. rex individuals hatched at a relatively small size, perhaps weighing just 15-20 pounds, making them vulnerable to both predation and temperature fluctuations. These juvenile tyrannosaurs would have benefited significantly from the insulation and camouflage that feathers could provide. As tyrannosaurs grew to their massive adult size at a remarkable rate, potentially gaining over 1,000 pounds annually during peak growth, their thermoregulatory needs would have shifted dramatically. This pattern of losing juvenile feathering during growth is observed in modern birds like ostriches and emus, whose chicks hatch with fluffy down that gives way to more specialized adult plumage. The fossil record of juvenile tyrannosaurs remains sparse, but this developmental hypothesis suggests T. rex may have been feathered as juveniles before losing most or all feathers as adults.

The Complex Picture: Partial Feathering Hypotheses

Rather than an all-or-nothing scenario, many paleontologists now favor a nuanced hypothesis of partial feathering for T. rex. Under this model, T. rex might have retained feathers on specific body regions while displaying scales elsewhere. Areas with potential feathering include the dorsal midline (forming a mane-like structure along the back), the neck region (for display purposes), or limited patches on the body that served specific functions. This patchy distribution would mirror that of modern flightless birds like cassowaries, which have bare, scaly legs but feathered upper bodies. Such an arrangement would allow T. rex to benefit from feathers for display, species recognition, or limited insulation while avoiding overheating issues associated with complete coverage. The partial feathering hypothesis reconciles the seemingly contradictory evidence of the scaly skin impressions with the evolutionary inheritance of feathers from smaller tyrannosaur ancestors.

Display and Communication: Function Beyond Insulation

Feathers serve many biological functions beyond thermal regulation, with display and communication being particularly significant. In modern birds, colorful or elaborate feather structures play crucial roles in mate attraction, territorial displays, and species recognition. If T. rex retained feathers into adulthood, they likely served similar communicative purposes rather than primarily for insulation. Potential display structures might have included colorful feather crests, manes along the neck or back, or distinctive patterns that signaled age, sex, or individual identity to conspecifics. Such features would have been particularly valuable during breeding seasons when establishing dominance hierarchies or attracting mates. The use of feathers for display would explain why T. Rex might retain them in specific body regions even after growing to a size where full-body insulation became unnecessary or problematic, providing evolutionary advantages that outweighed thermoregulatory concerns.

Scientific Debates and Competing Hypotheses

The question of T. rex feathering remains actively debated within the paleontological community, with respected scientists championing different interpretations of the available evidence. Proponents of the “mostly scaly” hypothesis point to the discovered skin impressions and thermoregulation challenges faced by large animals, arguing that adult T. rex likely resembled modern elephants in shedding most of their ancestral body covering. Advocates for feathered reconstructions emphasize the clear evolutionary relationship between tyrannosaurids and other feathered theropods, arguing that the burden of proof should be on demonstrating feather loss rather than retention. A middle ground position suggests regional feathering, with different body parts exhibiting different coverings based on functional needs. These competing hypotheses reflect broader methodological approaches in paleontology, with researchers weighing the relative importance of direct fossil evidence against phylogenetic inference from related species.

Fossil Limitations: What We Don’t Know

The fragmentary nature of the fossil record creates significant limitations when investigating T. rex’s integumentary coverings. Skin impressions are exceedingly rare, representing only tiny fractions of the animal’s total surface area, often less than 1%. The preservation of feathers requires exceptional conditions, as these delicate structures typically decompose long before fossilization can occur. Most T. rex specimens come from environments that favored bone preservation but destroyed soft tissues, creating a substantial bias in the evidence available to researchers. Additionally, the fossil record has yielded few juvenile T. rex specimens, precisely the growth stage when feathers would have been most likely if the ontogenetic hypothesis is correct. These preservation biases mean our picture of T. rex remains incomplete, with significant room for discoveries to dramatically shift scientific consensus in the future.

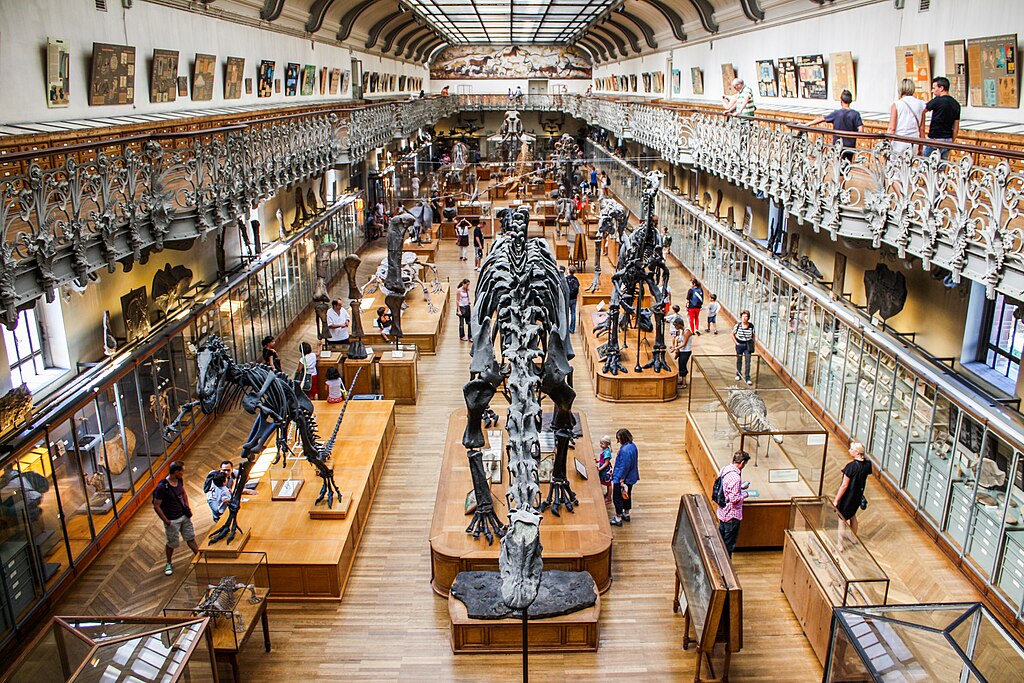

Cultural Impact: Feathers and the Popular Image of Dinosaurs

The potential presence of feathers on iconic dinosaurs like T. rex has sparked significant resistance in popular culture, where scaly, reptilian depictions have dominated for generations. When the film Jurassic Park debuted in 1993, its revolutionary portrayal of dinosaurs as active, dynamic animals represented cutting-edge science, yet its scaly T. rex now appears increasingly outdated as research progresses. Subsequent films and media have largely maintained the traditional scaly appearance, with the director of Jurassic World explicitly rejecting feathered designs to maintain visual continuity with earlier films. This reluctance reflects a broader cultural attachment to familiar dinosaur imagery that extends beyond entertainment into museums, toys, and educational materials. The tension between scientific advances and cultural inertia highlights how dinosaur depictions occupy a unique position at the intersection of scientific knowledge and cultural iconography, with accurate representations often lagging decades behind current research.

The Current Scientific Consensus

The most current scientific consensus regarding T. rex’s appearance embraces complexity rather than simple yes-or-no answers about feathering. Most paleontologists now consider it plausible that T. rex underwent significant changes throughout its life cycle, potentially hatching with a downy covering that was progressively reduced as it grew to adult size. The consensus acknowledges that different body regions likely featured different integumentary structures, with scales definitively present in some areas based on fossil evidence. Many experts suggest that any adult feathering was probably limited to the dorsal region or used for display purposes rather than covering the entire body. This nuanced view accommodates both the direct evidence from skin impressions and the evolutionary context of tyrannosaur ancestry. The scientific community generally agrees that simplistic all-feathered or all-scaled depictions likely misrepresent the complex reality of this iconic dinosaur’s appearance.

Conclusion

The question of whether T. rex had feathers exemplifies how paleontology continues to evolve as new evidence emerges and analytical techniques improve. While direct fossil evidence shows that certain portions of adult T. rex bodies were covered in scales, the evolutionary relationships and developmental biology suggest a more complex picture than the completely scaly monster of traditional imagination. Juvenile T. rex likely sported more extensive feathering than adults, and even adult specimens may have retained feathered regions for display or species recognition alongside predominantly scaly skin. As with many aspects of prehistoric life, the truth appears more nuanced than either extreme position would suggest. What remains clear is that our understanding of these magnificent creatures continues to develop, with each discovery bringing us closer to accurately reconstructing the appearance and biology of the tyrant king that ruled the Late Cretaceous world.