The Earth’s geological record serves as a vast library of past life, with certain locations emerging as exceptional chapters in this planetary narrative. These fossil hotspots—areas with extraordinary concentrations of well-preserved remains—continue to unveil the mysteries of ancient organisms and ecosystems. From Canadian mountainsides revealing the earliest complex animals to Mongolian deserts yielding spectacular dinosaur remains, these paleontological treasures offer invaluable insights into evolution and extinction events. Fossil hotspots aren’t merely random occurrences but rather the result of specific geological, chemical, and environmental conditions that create the perfect preservation circumstances. Let’s explore the world’s most productive fossil sites and understand why they remain fertile ground for discoveries that continually reshape our understanding of life’s history.

The Burgess Shale: Window into the Cambrian Explosion

High in the Canadian Rockies lies one of paleontology’s most significant treasures, the Burgess Shale, a Middle Cambrian deposit approximately 508 million years old. This UNESCO World Heritage site continues yielding exquisitely preserved soft-bodied organisms that normally wouldn’t fossilize, including bizarre creatures like Anomalocaris, Hallucigenia, and Opabinia. The site’s importance stems from its documentation of the “Cambrian Explosion,” when animal diversity rapidly expanded, setting the stage for all subsequent animal evolution. The exceptional preservation resulted from underwater mudslides that transported organisms to oxygen-poor environments where decomposition was limited, and fine sediments captured detailed impressions of soft tissues. Even after more than a century of research since Charles Walcott’s initial discovery in 1909, scientists continue finding new species here, demonstrating how productive fossil beds can remain when approached with new techniques and perspectives.

The Gobi Desert: Dinosaur Nesting Grounds

Mongolia’s Gobi Desert has emerged as one of the world’s most productive dinosaur fossil regions, particularly famous for yielding the first dinosaur eggs and nests ever discovered. The arid conditions and ancient dune environments create perfect preservation conditions that have remained largely undisturbed for millions of years. Perhaps most famous are the fighting dinosaurs—a Velociraptor and Protoceratops preserved in combat—and the tremendous number of Oviraptor specimens found brooding their nests, which revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur behavior. The Gobi’s continued productivity stems from its vast unexplored areas and the exposure of new fossils through natural erosion processes that constantly reveal fresh specimens. Political opening in recent decades has allowed for more international expeditions, ensuring this region continues delivering groundbreaking discoveries, including new species of dinosaurs, mammals, and prehistoric birds that lived during the Cretaceous period.

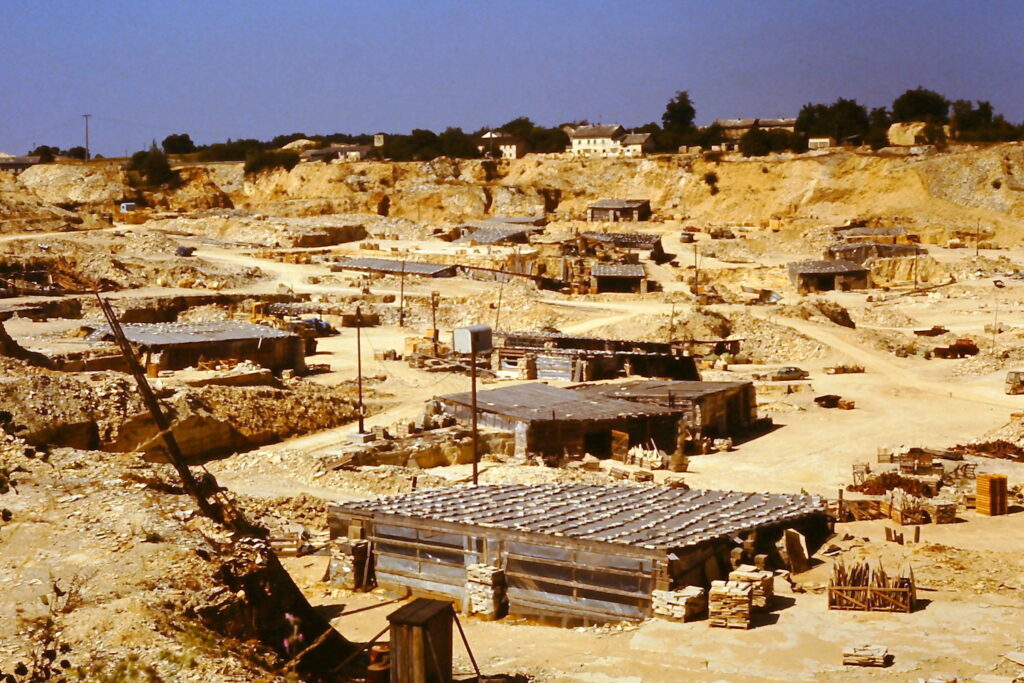

Messel Pit: Preserved Ecosystem in Germany

The Messel Pit in Germany represents one of the most remarkable Eocene fossil sites, preserving an entire 47-million-year-old ecosystem in extraordinary detail. This former shale quarry contains fossils with soft tissues, stomach contents, skin impressions, and even original coloration patterns preserved through unique lake-bed conditions where fine sediments and anoxic waters prevented decomposition. Among its treasures are early horses, primitive bats, countless insects with preserved iridescent colors, and the famous “Ida” (Darwinius masillae), a primate specimen so complete it includes fur impressions and stomach contents. The site’s continued productivity stems from meticulous excavation techniques that carefully separate the thin layers of oil shale, revealing specimens that would be destroyed using conventional methods. Each newly exposed layer has potential for discovery, making Messel an ongoing source of paleontological information despite decades of scientific extraction, with researchers still regularly finding species new to science as they carefully work through its sediments.

Green River Formation: America’s Fossil Lake System

Spanning Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah, the Green River Formation preserves an extensive Eocene lake system that existed 52-48 million years ago, producing some of the world’s most beautiful and abundant vertebrate fossils. This formation is renowned for complete fish specimens preserved in such detail that scales, fins, and even internal structures remain visible, often appearing as if the animal died yesterday rather than 50 million years ago. The site’s remarkable preservation resulted from seasonal layering of sediments creating varves (annual layers) in deep, oxygen-poor lake bottoms where scavengers couldn’t operate and bacterial decay was limited. Beyond fish, the formation yields crocodiles, turtles, birds, mammals, insects, and plants, providing a comprehensive picture of an entire ancient ecosystem. The site’s continued productivity derives from its vast geographical extent and the commercial fossil industry that continuously exposes new material, with scientific discoveries often emerging from commercially extracted slabs destined for museums or private collections.

The Karoo Basin: South Africa’s Evolutionary Laboratory

South Africa’s Karoo Basin represents one of the world’s most continuous and extensive fossil records, documenting nearly 100 million years of terrestrial evolution from the Late Carboniferous through the Early Jurassic periods. This vast sequence captures the transition from mammal-like reptiles to true mammals, making it crucial for understanding the evolution of key mammalian characteristics. The basin’s productivity stems from extensive erosion, exposing different periods across a vast landscape, creating what amounts to a natural evolutionary laboratory. Significant discoveries include countless therapsid fossils (mammal ancestors) and evidence of the end-Permian mass extinction, Earth’s most devastating extinction event. The site continues delivering new fossils because of its sheer size and the ongoing erosional processes that constantly expose fresh material from different periods. Additionally, improved understanding of stratigraphic relationships allows paleontologists to target specific layers representing critical evolutionary transitions or extinction boundaries, ensuring the Karoo remains at the forefront of evolutionary research.

Liaoning Province: China’s Feathered Dinosaur Treasury

The Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota in China’s Liaoning Province has revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur evolution and the origin of birds through its exceptional preservation of feathered dinosaurs and early birds. This fossil hotspot preserves soft tissues, including feathers, skin, and internal organs, due to fine volcanic ash deposits that rapidly buried organisms following catastrophic eruptions. Among its most famous discoveries are Sinosauropteryx, the first non-avian dinosaur confirmed to have feathers, and Microraptor, a four-winged dinosaur that provided crucial insights into flight evolution. The site’s continued productivity stems from its extensive geographical area and the careful excavation work performed by both professional paleontologists and local farmers who have developed expertise in recognizing significant specimens. The economic incentives for discovering complete specimens have created a systematic exploration of these deposits that continues yielding new species. Additionally, improvements in analytical techniques allow researchers to extract more information from existing specimens, including microscopic details of feather structure and chemical signatures revealing original coloration patterns.

La Brea Tar Pits: Ice Age Time Capsule

Located in the heart of Los Angeles, the La Brea Tar Pits represent one of the world’s richest Ice Age fossil deposits, preserving an exceptional record of Pleistocene life from the past 50,000 years. This urban paleontological wonder continues producing new specimens as the natural asphalt seeps acted as perfect predator traps—animals became stuck in the sticky substance, attracting carnivores that themselves became trapped, creating concentrated deposits of predators and prey. The site has yielded over a million specimens representing more than 600 species, from massive Columbian mammoths and saber-toothed cats to tiny insects and plant remains. La Brea’s continued productivity stems from ongoing excavation projects that still recover approximately 100 fossils daily despite over a century of scientific extraction. The site’s unique preservation potential extends to microfossils, plant materials, and even ancient DNA, allowing researchers to reconstruct entire ecosystems and track how species responded to climate change leading up to the end of the last Ice Age, providing valuable context for understanding modern climate shifts.

Solnhofen Limestone: Archaeopteryx and Ancient Lagoons

Germany’s Solnhofen Limestone deposits represent one of the most famous Jurassic fossil sites, preserving 150-million-year-old organisms in remarkable detail within what were once lagoons isolated from the Tethys Sea. The formation’s claim to fame is Archaeopteryx, the iconic transitional fossil between dinosaurs and birds, with specimens showing both reptilian features like teeth and a bony tail alongside unmistakable feather impressions. The exceptional preservation results from fine-grained limestone created in oxygen-poor lagoon bottoms where animals that fell in were rarely disturbed by scavengers or currents. Beyond Archaeopteryx, the limestone yields exquisitely preserved pterosaurs, fish, insects, crustaceans, and even delicate jellyfish impressions. The site’s continued productivity comes from its extensive commercial quarrying operations for architectural limestone, which regularly expose new fossil specimens as fresh layers are extracted. Each new Archaeopteryx specimen (currently 12 known) has provided additional details about this crucial evolutionary transition, with the most recent discoveries emerging from private collections and commercial operations that recognized their scientific importance.

The Kem Kem Beds: North Africa’s Cretaceous River System

Morocco’s Kem Kem Beds represent one of the most dangerous ancient ecosystems ever documented, preserving a Cretaceous river system that supported a remarkably high concentration of large predatory dinosaurs and massive aquatic predators. This formation continues yielding spectacular fossils, including the sail-backed Spinosaurus, the largest known predatory dinosaur, now understood to be semi-aquatic based on recent discoveries of its paddle-like tail. The site’s productivity stems from extensive erosion across southeastern Morocco and neighboring Algeria that constantly exposes new material, combined with a well-established local fossil trade that systematically explores these outcrops. The fossils themselves are preserved in ancient river channels where bones accumulated as concentrated deposits during flooding events. New research techniques, including CT scanning and geochemical analysis of teeth and bones, continue to extract fresh information from both newly discovered and previously collected specimens. The ongoing reinterpretation of this ecosystem provides crucial insights into predator-prey relationships in Cretaceous river systems and how multiple apex predators could coexist in a single environment through different feeding strategies and habitat partitioning.

The White Sea Coast: Dawn of Animal Life

Russia’s White Sea coastline preserves some of Earth’s oldest complex animals in the Ediacaran biota, strange soft-bodied organisms that lived between 570-540 million years ago, predating the Cambrian Explosion. These ancient impressions include disc-shaped, frond-like, and quilted organisms, unlike anything alive today, representing Earth’s first experiment with complex multicellular life. The site’s exceptional preservation resulted from organisms being rapidly buried by fine sediments and then covered by microbial mats that created detailed impressions before decomposition could occur. The White Sea’s continued productivity stems from ongoing coastal erosion that constantly exposes new fossil-bearing surfaces, combined with seasonal freeze-thaw cycles that help split rocks along bedding planes where fossils are preserved. Recent expeditions continue discovering new Ediacaran species, helping resolve questions about whether these organisms represent early animals, fungi, or an entirely separate evolutionary experiment that ultimately failed. Advanced imaging techniques, including laser surface scanning, now capture three-dimensional data from these impressions, revealing previously undetectable details about how these organisms lived and potentially moved.

Rancho La Brea: The Perfect Preservation Conditions

The remarkable preservation conditions at Rancho La Brea deserve specific examination beyond merely cataloging its impressive specimens. The asphalt seeps created unique chemical environments that prevented normal decomposition processes through both physical and antimicrobial properties. The sticky nature of the tar preserved articulated skeletons by preventing scattering of remains, while the hydrophobic properties of the asphalt repelled water and created anaerobic conditions hostile to most decomposing bacteria. Additionally, the asphalt itself contains compounds that actively inhibit microbial growth, functioning as a natural preservative for organic material, including bone collagen, plant matter, and even ancient insect exoskeletons. The continued exceptional preservation extends to microfossils, including pollen and diatoms that provide detailed environmental data across millennia. Modern research at La Brea now includes stable isotope analysis of bones and teeth to reconstruct ancient food webs, ancient DNA extraction from preserved collagen, and microscopic examination of wear patterns on teeth that reveal dietary preferences. These advanced techniques continue extracting new information from both recently excavated and previously collected specimens, demonstrating how technological advances can extend a fossil site’s scientific productivity.

The Antarctic Peninsula: Dinosaurs on Ice

Despite its current frozen state, Antarctica’s geological record preserves evidence of much warmer periods when dinosaurs and lush forests thrived near the South Pole. The Antarctic Peninsula has emerged as a crucial fossil hotspot,ot revealing how polar ecosystems functioned during the Mesozoic Era when Antarctica occupied similar latitudinal positions but experienced dramatically different climate conditions. Recent expeditions have recovered plant fossils indicating diverse forest ecosystems adapted to seasonal darkness, alongside dinosaur remains that prove these animals could survive in polar conditions with months of winter darkness. The area’s continued productivity stems from improved logistics allowing more extensive field seasons, combined with retreating ice sheets exposing previously inaccessible rock formations. The unique taphonomic conditions in Antarctica include minimal human disturbance, creating pristine contexts for understanding fossil deposition, while the cold, dry conditions help preserve organic compounds rarely found elsewhere. Each field season yields discoveries despite the logistical challenges, with recent findings including evidence of how forests recovered after the end-Cretaceous extinction event and how marine reptiles like plesiosaurs adapted to cold-water environments.

Why Fossil Hotspots Keep Delivering: The Science Behind Productivity

The continued productivity of major fossil hotspots stems from multiple interrelated factors beyond simple luck or abundance. First, many productive sites represent depositional environments that operated continuously over long periods, creating thick sequences that preserve evolutionary transitions and responses to environmental changes. Second, the most productive sites typically feature exceptional preservation conditions—chemical, physical, or biological factors that inhibit normal decomposition processes and preserve details rarely found elsewhere. Third, exposure mechanisms like erosion, quarrying, or construction continuously reveal new material even after decades of collection. Fourth, technological advances regularly allow researchers to extract new information from previously studied specimens through techniques like CT scanning, synchrotron imaging, and molecular analysis. Finally, conceptual advances in paleontology mean scientists often return to well-known sites with new questions and perspectives, finding evidence for phenomena they weren’t previously looking for. Together, these factors ensure that major fossil sites continue yielding scientific insights long after their initial discovery, with each generation of paleontologists finding fresh value in these geological treasures through improved methods and evolving research questions.

The Role of Fossil Hotspots in Tracing Life’s Story

The world’s fossil hotspots represent more than mere collections of old bones and impressions—they are irreplaceable archives of Earth’s biological history. Each site provides unique windows into ancient worlds through the specific conditions that created and preserved its fossils. As excavation techniques advance and new analytical methods emerge, these sites continue revealing their secrets, often in ways their original discoverers could never have imagined. From microscopic details of cell structures to continent-scale patterns of evolution and extinction, fossil hotspots remain vital to understanding life’s past—and potentially its future. As climate change and human development threaten both known and undiscovered sites, the scientific community faces the dual challenge of extracting maximum information from these geological treasures while ensuring their preservation for future generations of researchers armed with even more advanced techniques.