For decades, you might have learned in school that Homo erectus proudly claimed the title of first human traveler beyond African shores. That neat narrative has been the bedrock of paleoanthropology classes worldwide. Everyone accepted it, taught it, repeated it.

Yet a remarkable discovery in a small medieval village nestled in the Georgian hills is making scientists rethink everything they thought they knew. Fossils unearthed at Dmanisi have revealed something startling: multiple human species may have wandered out of Africa together, not just one pioneer. The implications are huge. If true, it means you need to reimagine the story of your earliest ancestors as far more complex than anyone previously imagined.

The Puzzling Fossils from Dmanisi

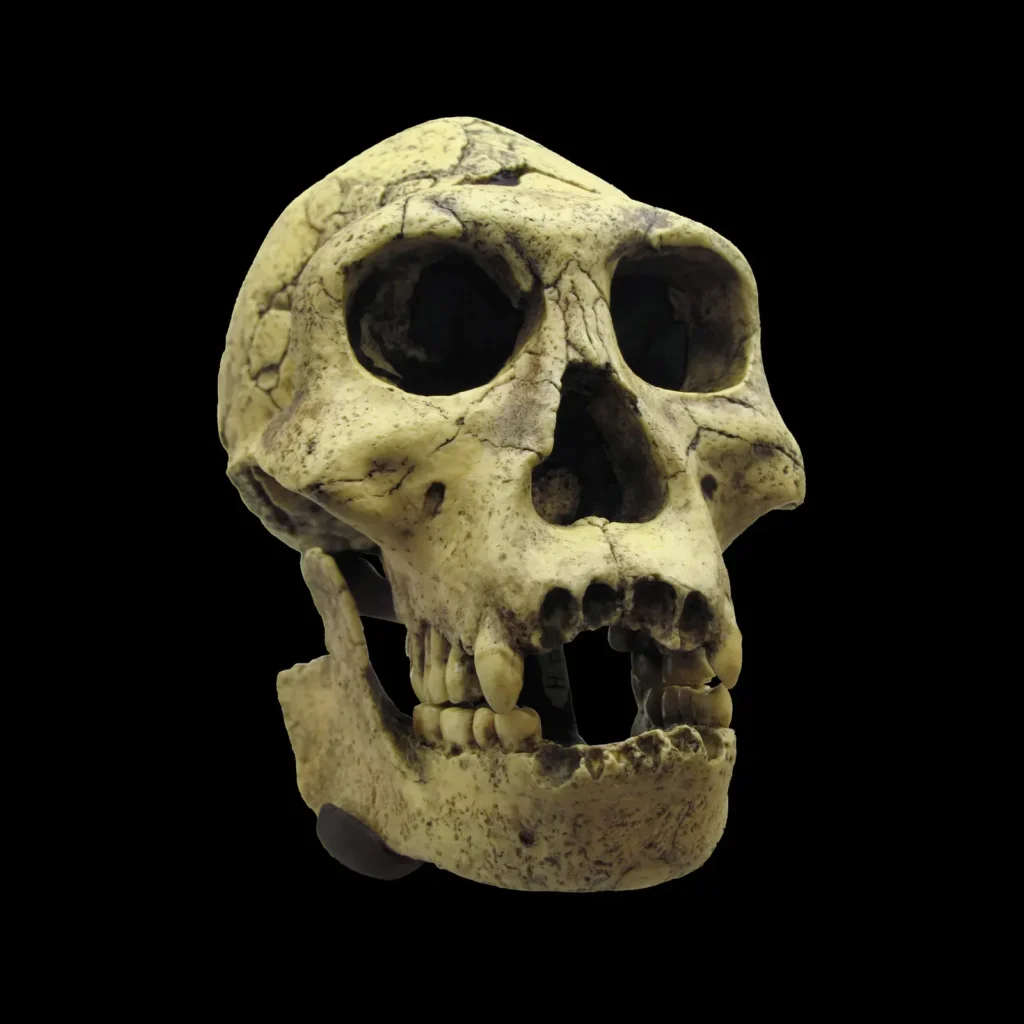

The debate centers on the Dmanisi fossils, five skulls found in the Republic of Georgia between 1999 and 2005, nestled beneath the ruins of a medieval town. These hominin remains, discovered in 1991 by David Lordkipanidze, are dated to 1.8 million years ago, making them the earliest dated human remains in Eurasia. Yet here’s the thing that confuses everyone: they don’t look alike at all.

Some are larger than others, particularly Skull 5, which has a tiny braincase but a massive, protruding face. The level of variation is striking. Some researchers explain this as a difference in sexes within the same species, while others argue that it represents two distinct species living together.

Why Scientists Turned to Teeth

Previous analyses of the Dmanisi fossils mostly focused on the skulls. In the new study, published Dec. 3 in the journal PLOS One, researchers instead concentrated on similarities and differences among the teeth. Teeth, you see, tell a different story than bones.

Skulls aren’t always the best way to determine the species. Bone can be warped or crushed over millions of years. Tooth enamel, on the other hand, is strong and has species markers which stand the test of time. The research team analyzed fossilized teeth from three Dmanisi specimens, comparing them with teeth from other ancient species. They analyzed 24 fossilized teeth from three individuals found at Dmanisi, comparing them with 559 teeth from other species, including Homo erectus, Homo habilis, and even earlier ancestors like Australopithecus.

Two Species, Not One

The analysis, published in PLOS One, revealed that the teeth from Dmanisi could be split into two distinct groups. One group’s teeth showed features similar to Australopithecus, which are believed to be closer to the common ancestor of humans and apes. The other group’s teeth were more similar to those of early humans like Homo erectus. This was no minor variation between individuals.

Mark Hubbe, a professor of anthropology at the University of Tennessee and co-author of the study, explained that there were likely more than one species that occurred in the Dmanisi region. One, dubbed Homo georgicus, seemed more closely related to predecessors of humans known as australopiths, while the other, Homo caucasi, appeared more similar to early human species. The dental differences were too pronounced to dismiss as simple sexual dimorphism.

What This Means for Human Migration

If you accept these findings, the traditional story collapses. For years, scientists believed that Homo erectus was the first human species to venture out of Africa around 1.8 million years ago. However, a recent study of fossilized teeth from the Dmanisi site suggests the story is more complicated.

The biggest implication is that there was an earlier, and more ‘primitive’ species that migrated out of Africa than generally thought, which is quite interesting. The discovery of different species in the Dmanisi fossils raises the possibility that other, more primitive human species made the journey earlier. This fundamentally challenges what you’ve been taught about our evolutionary journey.

Evidence from Stone Tools and Other Sites

Stone tools that possibly date to as far back as 2.48 and 2.1 million years from respectively Zarqa Valley, Jordan, and Shangchen, China, could indicate that an earlier hominin species left Africa. These tools predate the emergence of Homo erectus, adding weight to the argument that other species left first.

In their paper, the researchers argue that stone tools from Jordan and Romania that predate the emergence of Homo erectus support the idea that the first human to leave Africa was in fact related to the older Homo habilis. The archaeological record, it seems, has been whispering these clues for years. Scientists are only now starting to listen properly. They therefore suggest that the two species found at Dmanisi probably evolved from different Homo habilis populations that lived in different regions of Eurasia over a long period.

The Skeptics Weigh In

Let’s be real here: not everyone is convinced. Baab cautioned that these new findings do not conclusively prove there was more than one species at Dmanisi. For instance, she noted the new study’s analysis of teeth from the lower jaw suggested these fossils might belong just to H. erectus, and not two species.

Karen Baab, a paleoanthropologist at Midwestern University, points out that the differences in the Dmanisi teeth might still be explained by natural variation within a single species of Homo erectus. While Baab acknowledges that multiple species could have coexisted in Dmanisi, she cautions that the simpler explanation might be that the fossils belong to one highly variable species rather than two distinct ones. The debate rages on. Science rarely offers clean, simple answers when you dig into the distant past.

Rethinking Human Evolution

The level of speciation seen in the Dmanisi fossils suggests that the different clades were beginning to diverge before leaving Africa. If the Dmanisi specimens cannot be taxonomically grouped with Homo erectus, it raises the possibility that early Homo evolution had multiple episodes of cladogenesis, where some of them may have started in Africa, and others outside Africa. The diversity of the Dmanisi hominin fossils, and the possibility that they represent more than one species, adds to this discussion demonstrating that a revision of our current models for the expansion of Homo out of Africa is required.

This isn’t just academic hairsplitting. It fundamentally changes how you understand human origins. Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London who did not take part in this study, stated he agrees with the authors that Dmanisi probably has more than one lineage represented. When respected experts start agreeing that the old models need updating, you know something significant is happening in the field.

The evidence from Dmanisi paints a picture of early human migration that’s messier, more chaotic, and honestly more fascinating than the clean linear progression you might have imagined. Multiple species likely coexisted, competed, perhaps even interbred as they explored new territories beyond Africa. The journey wasn’t a single heroic march led by Homo erectus alone. It was a complicated story involving different groups, different adaptations, and different outcomes.

So what do you think about rewriting one of the most fundamental chapters in human history? Did multiple species really leave Africa together nearly two million years ago, or are we looking at natural variation within a single adaptable species? The fossils from that Georgian hillside continue to challenge everything scientists thought they knew. Maybe that’s exactly what makes paleoanthropology so captivating: every new discovery has the power to reshape your understanding of where you came from.