Beneath Alaska’s frozen landscape lies a treasure trove of human history that’s just beginning to tell its story. As climate change accelerates the melting of glaciers and permafrost, archaeologists are racing against time to uncover and preserve ancient settlements that have remained hidden for thousands of years. You’re about to discover how cutting-edge ground-penetrating radar technology is revolutionizing our understanding of Alaska’s earliest inhabitants, revealing civilizations that thrived in conditions we can barely imagine surviving today.

The Silent Witnesses Beneath the Ice

Deep beneath Alaska’s glacial surfaces, ancient human settlements have been waiting in frozen silence for millennia. Stratified layers of ice-preserved evidence of hunters, animals, and weapons are emerging, evidence of activities dating back thousands of years. These frozen time capsules hold secrets that could rewrite our understanding of how early humans survived and thrived in some of the planet’s most challenging environments.

What makes these discoveries particularly remarkable is their pristine condition. Unlike archaeological sites in temperate climates where organic materials decay, Alaska’s frozen environment has acted as a natural preservative. You can find grass cut when Shakespeare walked the Earth still crisp and green, baskets with their woven patterns intact, and tools that look as if they were just set down yesterday.

Revolutionary Technology Penetrates Ancient Secrets

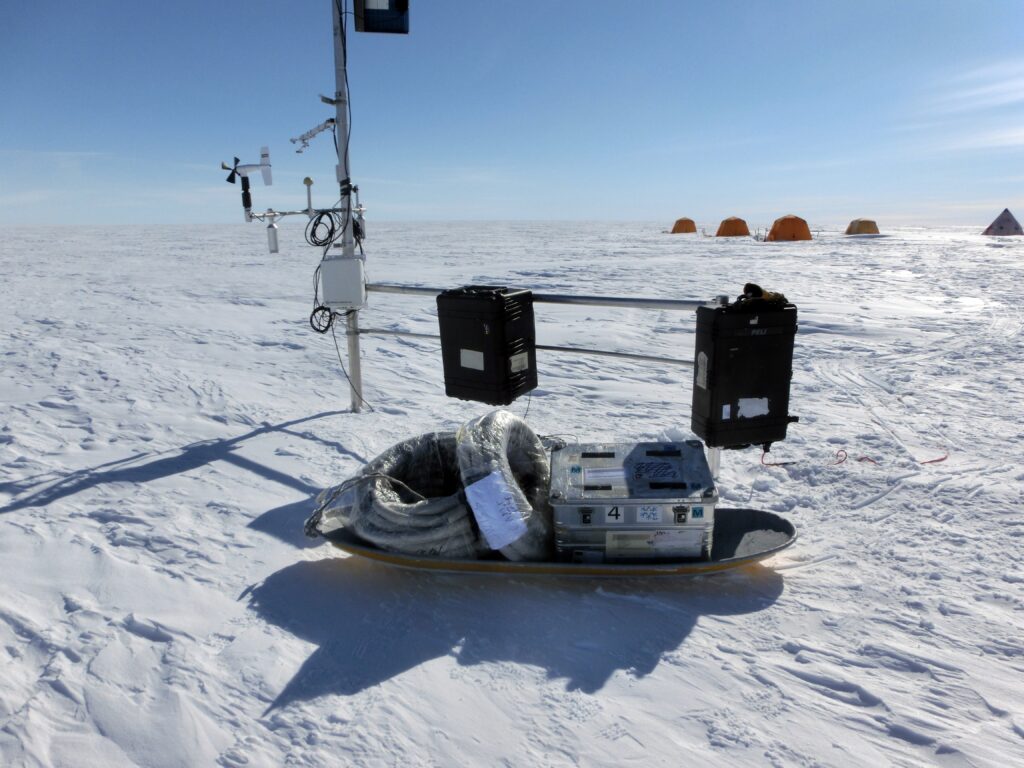

Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) offers many advantages for assessing archaeological potential in frozen and partially frozen contexts in high latitude and alpine regions. This sophisticated technology works by sending electromagnetic pulses into the ground and analyzing the signals that bounce back, creating detailed images of what lies beneath the surface without disturbing the archaeological record.

The technology has proven particularly effective in Alaska’s unique environment. Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) collected over the surface of a glacier provides high-resolution, spatially-extensive measurements of snow thickness and water content. You might think ice would interfere with radar signals, yet the opposite is true. The low conductivity of ice actually allows radar waves to penetrate much deeper than in other environments, revealing structures buried under several meters of frozen material.

Inupiat Villages Emerge from Permafrost

In Kobuk Valley National Park, a GPR investigation of an early contact period Inupiat settlement revealed an earlier, deeper occupation in the permafrost just beneath the known site. This groundbreaking discovery suggests that indigenous communities inhabited these locations for far longer than previously understood, with multiple generations building their homes on the same sacred grounds.

The implications of this find extend far beyond simple chronology. These layered settlements provide you with unprecedented insight into how Arctic peoples adapted to changing environmental conditions over centuries. Each buried layer represents a different chapter in their story, showing how they modified their building techniques, hunting strategies, and community organization in response to climatic shifts.

Cape Krusenstern’s Ancient Beach Hunters

At Cape Krusenstern National Monument, GPR revealed complex patterned ground created by the freeze-thaw cycle at the Old Whaling beach ridge, while multi-year GPR data collected at this location illustrates temporal variations in the permafrost table. The Old Whaling culture discovered here represents one of Alaska’s most enigmatic ancient civilizations.

What is now Cape Krusenstern National Monument in northwestern Alaska contained a unique artifact assemblage and house forms unlike any other site yet (or since) discovered in Alaska. The site also contained whale bones, and large weapon heads and butchering tools. These massive marine mammals required sophisticated hunting techniques and communal effort, suggesting complex social structures that coordinated dangerous open-water hunts.

The Challenge of Arctic Archaeology

These settings pose several challenges for GPR, including extreme velocity changes at the interface of frozen and active layers, cryogenic patterns resulting in anomalies that can easily be mistaken for cultural features, and the difficulty in accessing sites and deploying equipment in remote settings. Working in Alaska’s harsh conditions pushes both technology and human endurance to their limits.

Researchers must navigate not only the physical challenges of reaching remote sites but also the interpretative complexities of frozen ground. Many components of these patterns, if viewed in isolation, could easily be mistaken for house perimeters on the basis of size and shape. This means archaeologists must develop specialized skills to distinguish between natural freeze-thaw patterns and genuine human-made structures buried in the permafrost.

Racing Against Climate Change

The urgency of this work cannot be overstated. Today increasingly violent weather has driven Nunalleq to the brink of oblivion. In summer everything looks fine as the land dons its perennial robe of white-flowering yarrow and sprigs of cotton grass that light up like candles when the morning sun hits the tundra. Yet beneath this deceptively peaceful surface, centuries of human history are disappearing as permafrost melts and coastal erosion accelerates.

At some sites, archaeologists literally work against the clock as rising sea levels and warming temperatures threaten to wash away irreplaceable cultural heritage. As the permafrost covering the site melted further, the team battled against the clock to remove each artefact before the site was lost to storms and the sea. Every summer brings new threats, making each field season a potential rescue mission.

Glimpses into Ancient Daily Life

The preserved settlements reveal intimate details about how ancient Alaskans lived their daily lives. The muddy square of earth is full of everyday things that the indigenous Yupik people used to survive and to celebrate life here, all left just as they lay when a deadly attack came approximately four to five centuries ago. Around the perimeter of what was once a large sod structure are traces of fire used to smoke out the residents – some 50 people, probably an alliance of extended families.

You can imagine walking through these ancient homes, seeing where families cooked their meals, crafted their tools, and told stories around central hearths. The level of preservation is so remarkable that researchers have found tattooing needles, carved masks, and even belts made from caribou teeth, providing vivid glimpses into the artistic and spiritual lives of these ancient communities.

Ice Patch Archaeology Reveals Hunter Pathways

Particularly rich areas include British Columbia, southern Yukon Territory and Northwest Territories in Canada, areas of interior Alaska and the Rocky Mountains in the western United States, and portions of Scandinavia and the European Alps. The significance of ice patch finds stems from their ability to provide unique insights into prehistoric cultural developments and technology since these perishable items are rare in the vast majority of archaeological contexts.

Alpine ice patches have emerged as some of archaeology’s most valuable resources, preserving organic artifacts that would have long since decomposed in other environments. These high-altitude hunting grounds reveal the sophisticated strategies ancient peoples used to track caribou migrations across Alaska’s interior mountains, providing evidence of seasonal movement patterns that connected coastal and inland communities.

Future Discoveries Waiting to be Found

Current technological advances suggest that we’ve only scratched the surface of what lies buried beneath Alaska’s ice. This study explores various testing techniques’ ability to identify activity areas across deeply stratified, open air archaeological sites. To determine the efficacy of different site testing techniques, a systematic ground penetrating radar and auger survey was completed at three sites in central Alaska.

As ground-penetrating radar technology continues to improve, archaeologists expect to find even more sophisticated settlements. The combination of enhanced processing power and refined interpretation techniques means future surveys will likely reveal complex village networks, trade routes, and ceremonial sites that connected Alaska’s ancient peoples across vast distances. Each new discovery adds another piece to the puzzle of human adaptation in the Arctic.

The frozen archives of Alaska continue to yield their secrets, transforming our understanding of human resilience and ingenuity in the face of extreme environmental challenges. These glacier vaults represent more than just archaeological sites; they’re libraries of human experience written in ice and stone, preserving the stories of peoples who not only survived but thrived in one of Earth’s most demanding environments. As technology advances and climate change accelerates, the race to document and preserve these irreplaceable windows into our past becomes ever more critical. What other ancient settlements lie waiting beneath Alaska’s ice, ready to reshape our understanding of humanity’s earliest chapters in the New World?