Picture this: a massive Triceratops munching on what looks like a modern wheat field, or a gentle Brontosaurus stretching its neck to graze on prairie grass. This image, burned into our minds by countless movies and documentaries, is completely wrong. The truth about what dinosaurs actually ate will flip everything you thought you knew about these ancient giants on its head.

The Great Grass Myth That Fooled Everyone

For decades, paleontologists and the general public alike believed that dinosaurs roamed across vast grasslands, much like the African savannas we see today. This misconception shaped our understanding of dinosaur behavior, diet, and even evolution itself. The reality is far more shocking than fiction.

Grass as we know it today – those green carpets covering our lawns and prairies – didn’t exist during most of the dinosaur era. The Cretaceous period, spanning from about 145 to 66 million years ago, was a time when flowering plants were just beginning their explosive evolution. Yet even then, grasses remained conspicuously absent from the prehistoric menu.

This revelation has forced scientists to completely reconsider how dinosaurs lived, what ecosystems looked like, and how these massive creatures managed to sustain themselves without one of Earth’s most abundant food sources today.

When Grass Actually Appeared on Earth

The fossil record tells us a surprising story about grass evolution. The earliest grass fossils date back only about 55 million years ago, well after the dinosaurs had vanished from Earth. Even more shocking is that widespread grasslands didn’t appear until roughly 20 million years ago during the Miocene epoch.

Think about it this way: if Earth’s history was compressed into a single year, dinosaurs would have ruled for about three weeks in late November and early December, while grasses wouldn’t appear until the very last week of the year. The timing mismatch is absolutely staggering.

Some recent studies suggest that primitive grass-like plants might have existed in very limited quantities during the late Cretaceous, but these were nothing like the extensive grasslands that dominate modern landscapes. They were rare, scattered, and certainly not a primary food source for any dinosaur species.

The Cretaceous Plant Kingdom Revolution

The Cretaceous period was actually witnessing one of the most dramatic botanical revolutions in Earth’s history. Flowering plants, or angiosperms, were exploding in diversity and abundance, completely transforming terrestrial ecosystems. This wasn’t a gradual change – it was an evolutionary explosion that happened relatively quickly in geological terms.

Before this revolution, the world was dominated by gymnosperms like conifers, cycads, and ginkgoes. These plants had ruled Earth’s landscapes for hundreds of millions of years, creating the backdrop against which dinosaurs evolved and thrived. The sudden appearance of flowering plants created new ecological opportunities and challenges.

Imagine a world where instead of grass, the ground was covered with ferns, mosses, and low-growing flowering plants that looked nothing like today’s familiar flora. This alien landscape was home to some of the most spectacular creatures ever to walk the Earth.

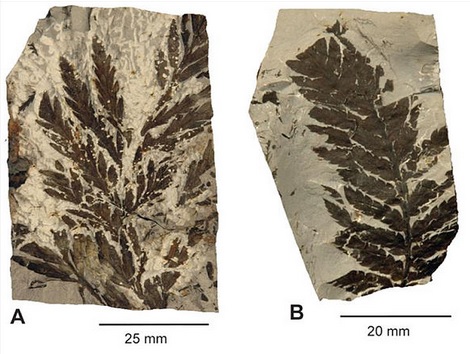

Ferns: The Dinosaur’s Green Carpet

If you want to understand what covered the Cretaceous ground where we might expect grass today, look no further than ferns. These ancient plants formed vast understory carpets beneath towering conifers and emerging flowering trees. Ferns were everywhere – from tiny delicate species to massive tree ferns that reached heights of 30 feet or more.

Many herbivorous dinosaurs, particularly smaller species, likely spent considerable time browsing on fern fronds. The protein content in young fern shoots would have provided essential nutrients, while the abundance of these plants made them a reliable food source. However, ferns also contain toxic compounds that would have limited how much dinosaurs could consume.

The diversity of Cretaceous ferns was mind-boggling compared to today’s relatively modest fern populations. Some species grew in dense colonies that stretched for miles, creating prehistoric “fern prairies” that filled ecological niches later occupied by grasslands.

Cycads: The Dinosaur’s Favorite Snack

Cycads were among the most important plants in dinosaur diets, and these remarkable survivors still exist today, though in much smaller numbers. These palm-like plants with thick, sturdy leaves were incredibly abundant during the Cretaceous and provided a high-energy food source for many herbivorous dinosaurs.

What made cycads particularly attractive to dinosaurs was their nutritious seeds and young leaves. However, these plants also contained powerful toxins as a defense mechanism. This created an evolutionary arms race between cycads developing stronger toxins and dinosaurs developing better ways to process or avoid these dangerous compounds.

Some paleontologists believe that certain dinosaur species may have developed specialized gut bacteria to help break down cycad toxins, similar to how modern koalas can digest poisonous eucalyptus leaves. This symbiotic relationship would have been crucial for survival in the Cretaceous world.

Conifers: The Towering Giants of Dinosaur Meals

Coniferous trees dominated the Cretaceous landscape, creating vast forests that stretched across continents. These weren’t just background scenery – they were the primary food source for many of the largest dinosaurs ever to exist. The long necks of sauropods like Brontosaurus and Diplodocus evolved specifically to reach the nutritious growing tips of these towering trees.

Conifer needles might seem like tough, unappetizing fare, but they were actually packed with essential nutrients and oils. The resin in these trees also provided antimicrobial properties that may have helped dinosaurs fight off infections and parasites. Different dinosaur species likely specialized in eating different parts of conifers – some preferred young shoots, others ate mature needles, and some may have consumed the protein-rich seeds.

The relationship between dinosaurs and conifers was so intertwined that some scientists believe certain tree species evolved specific characteristics in response to dinosaur browsing pressure. This co-evolutionary dance shaped both the predator and the prey over millions of years.

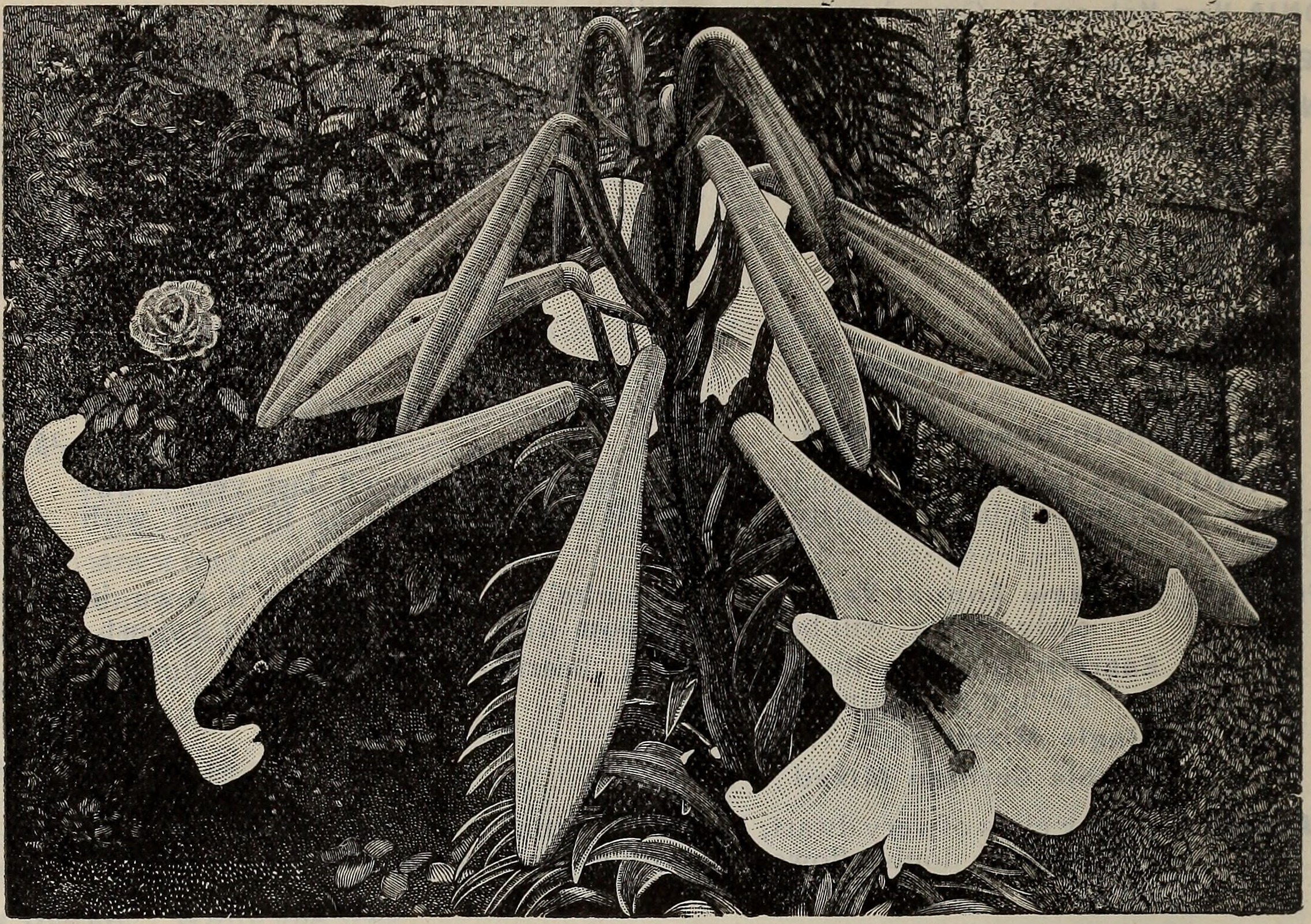

Early Flowering Plants: The New Kids on the Block

The emergence of flowering plants during the Cretaceous created entirely new dietary opportunities for dinosaurs. These early angiosperms were experimenting with every possible form and function, from tiny ground-hugging herbs to massive trees with spectacular blooms. The variety was absolutely stunning and unlike anything seen before in Earth’s history.

Many of these early flowering plants developed fruits and seeds as a way to attract animals for seed dispersal. Some dinosaurs likely became the first pollinators and seed dispersers, creating mutually beneficial relationships that would later be taken over by insects, birds, and mammals. This partnership between dinosaurs and flowering plants may have been crucial for both groups’ success.

The rapid evolution of flowering plants during the Cretaceous meant that dinosaur diets were constantly changing. Species that could adapt to new plant types had significant advantages, while those that couldn’t faced extinction pressure even before the famous asteroid impact.

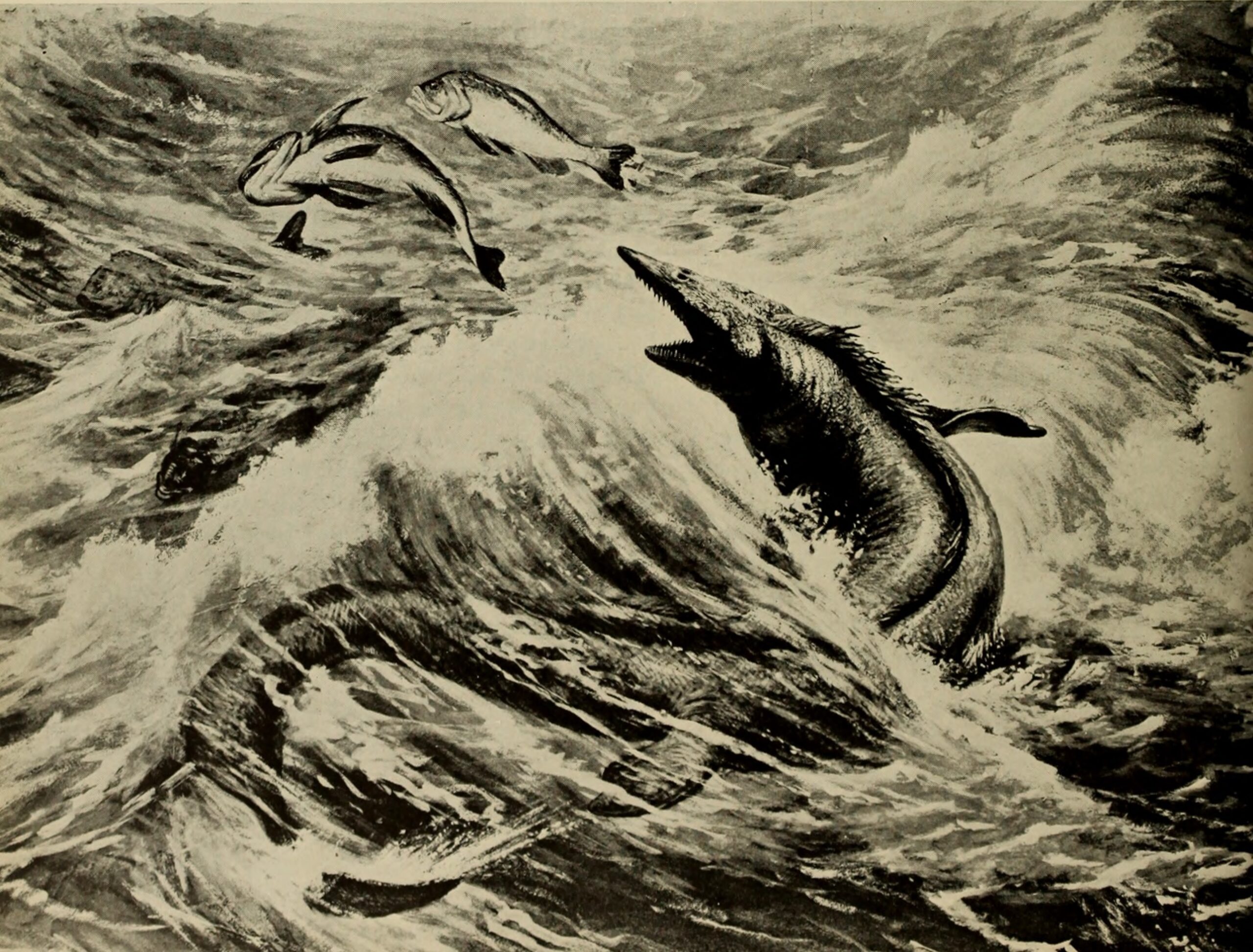

Aquatic Plants: The Forgotten Dinosaur Food

While much attention focuses on terrestrial plants, many dinosaurs also consumed aquatic vegetation. The warm, humid Cretaceous climate created extensive wetlands, swamps, and shallow seas filled with diverse aquatic plant communities. These waterlogged environments were like prehistoric salad bars for certain dinosaur species.

Hadrosaurs, or duck-billed dinosaurs, were particularly well-adapted for aquatic feeding. Their specialized beaks and dental batteries could efficiently process tough aquatic plants like water lilies, algae, and early aquatic grasses. The high water content of these plants would have been especially valuable in the hot Cretaceous climate.

Some of the largest dinosaurs may have spent considerable time in water, using their massive size to access deep aquatic vegetation that smaller animals couldn’t reach. This behavior would have been similar to modern hippos or elephants cooling off while feeding in rivers and lakes.

Seasonal Eating Patterns in the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous world experienced distinct seasonal patterns, and dinosaurs had to adapt their eating habits accordingly. During wet seasons, lush vegetation would have provided abundant food choices, while dry seasons forced dinosaurs to rely on hardier plants or stored fat reserves. This seasonal variation created complex migration patterns and feeding behaviors.

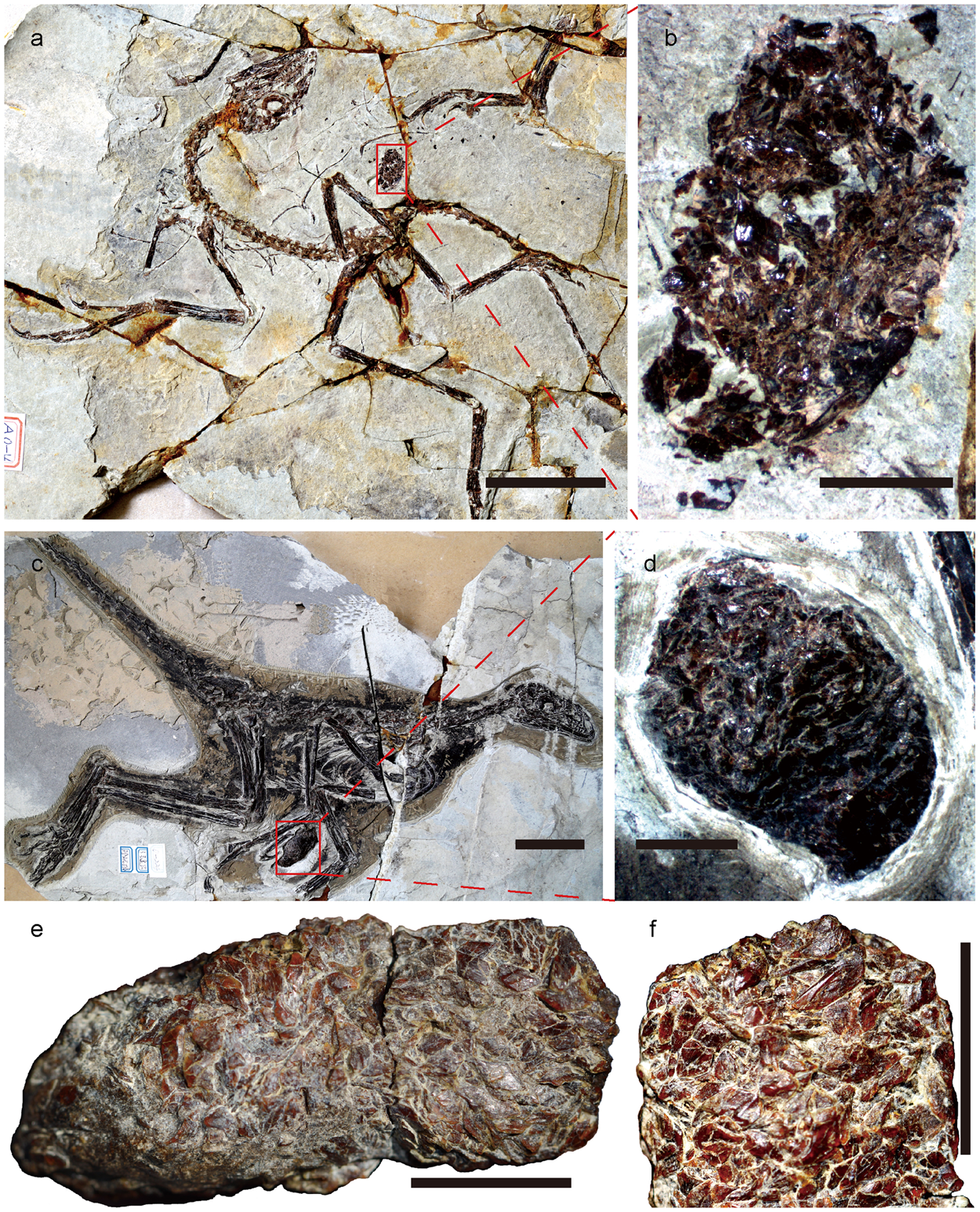

Evidence from dinosaur coprolites (fossilized feces) suggests that many species changed their diets dramatically throughout the year. Spring might bring tender new growth and flowering plants, while autumn could mean a shift to nuts, seeds, and more fibrous plant material. These seasonal adaptations were crucial for survival in the ever-changing Cretaceous environment.

Some dinosaur species may have developed specialized storage organs or behaviors to help them survive lean seasons. The ability to switch between different plant types based on availability would have been a major evolutionary advantage in this competitive prehistoric world.

Digestive Systems Built for a Grassless World

Dinosaur digestive systems evolved to process the tough, fibrous plants available in their grassless world. Many herbivorous dinosaurs developed incredibly long intestines and specialized stomach chambers to break down cellulose and extract nutrients from difficult plant material. These adaptations were far more complex than what modern grass-eating animals require.

The famous “gizzard stones” or gastroliths found with many dinosaur fossils were essential tools for grinding up tough plant material. These stones acted like internal millstones, helping dinosaurs break down everything from conifer needles to cycad fronds. The size and wear patterns on these stones tell us fascinating stories about dinosaur diets and digestive processes.

Some dinosaurs may have engaged in coprophagy – eating their own feces – to extract additional nutrients from partially digested plant material. This behavior, still seen in modern animals like rabbits, would have been particularly important when dealing with nutrient-poor or toxin-rich prehistoric plants.

How Dinosaurs Shaped Plant Evolution

The relationship between dinosaurs and plants wasn’t one-sided. Dinosaur herbivory pressure actually drove plant evolution in fascinating ways. Plants developed thorns, toxins, and tough fibers specifically to defend against dinosaur browsing. This evolutionary arms race created some of the most sophisticated plant defense systems ever seen.

The massive size of many herbivorous dinosaurs meant that plants had to evolve extreme defensive measures. Some developed chemical compounds so potent that they’re still used in modern pesticides. Others grew to enormous heights or developed armored bark to protect their vital growing tissues from dinosaur teeth and claws.

Paradoxically, dinosaur herbivory also helped plants by creating clearings in dense forests, allowing new species to colonize disturbed areas. This “ecosystem engineering” by dinosaurs may have accelerated plant evolution and created the diverse flowering plant communities that emerged during the Cretaceous.

The Real Cretaceous Ecosystem

Without grass to create open plains, the Cretaceous landscape looked completely alien to modern eyes. Dense forests of conifers and early flowering trees dominated higher elevations, while fern prairies and cycad groves filled lower areas. Wetlands and swamps created complex mosaics of aquatic and terrestrial plant communities.

The lack of grass meant that erosion patterns were completely different from today. Without grass roots to hold soil together, landscapes were more prone to dramatic changes from flooding and storms. This instability may have contributed to the rapid evolution of both plants and dinosaurs during this period.

The absence of grass also meant that fire patterns were different. Modern grasslands burn frequently and recover quickly, but Cretaceous plant communities may have been more vulnerable to fire damage. This could have created a patchwork of different successional stages that provided diverse habitats for various dinosaur species.

What This Means for Our Understanding of Dinosaurs

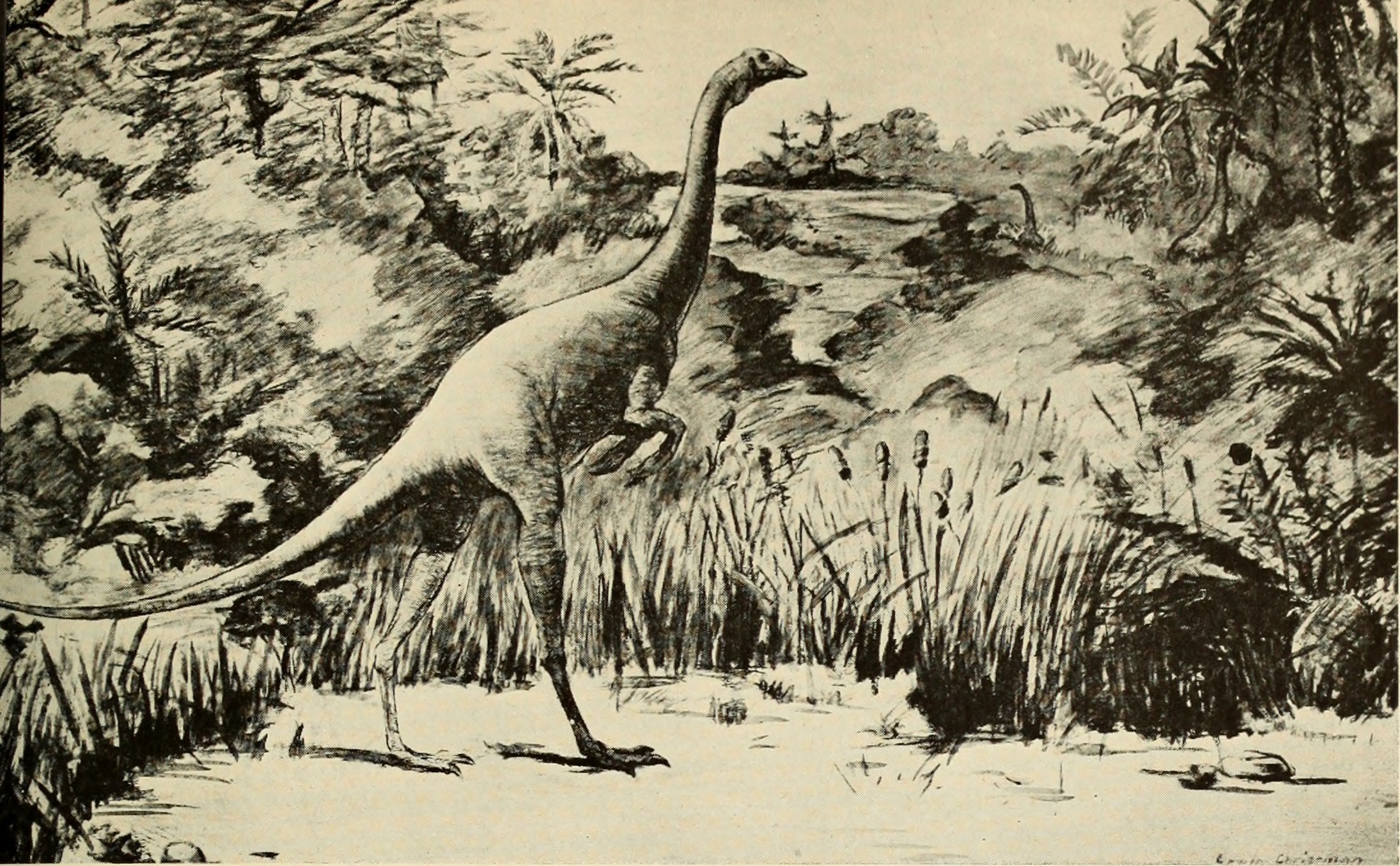

Realizing that dinosaurs lived in a grassless world fundamentally changes how we visualize these ancient creatures. Instead of the open savanna scenes popularized in movies, we should imagine dinosaurs moving through dense forests, fern-covered clearings, and swampy wetlands. This different landscape would have required different behaviors, social structures, and survival strategies.

The absence of grass also explains some puzzling aspects of dinosaur anatomy and behavior. The incredibly long necks of sauropods make perfect sense in a world where food grew on trees rather than on the ground. The complex dental batteries of hadrosaurs were designed for processing tough, fibrous plants rather than soft grass blades.

This revelation also helps us understand why dinosaurs became so large. In a world without easily accessible ground cover, being tall enough to reach tree canopies provided a significant advantage. The evolutionary pressure to grow larger was driven partly by the need to access high-growing food sources that smaller animals couldn’t reach.

Modern Implications of Ancient Diets

Understanding what dinosaurs actually ate provides crucial insights for modern conservation and ecosystem management. The complex relationships between Cretaceous plants and dinosaurs demonstrate how dramatically ecosystems can change over time. This knowledge helps us appreciate the delicate balance in today’s plant and animal communities.

The rapid evolution of flowering plants during the Cretaceous, partly driven by dinosaur herbivory, shows us how quickly ecosystems can transform under pressure. This has important implications for understanding how modern ecosystems might respond to climate change and human impacts.

Perhaps most importantly, the dinosaur-plant relationship reminds us that even the most successful species can face extinction when their food sources disappear. The lesson is clear: understanding and protecting plant diversity is crucial for maintaining the complex web of life that supports all animals, including humans.

The truth about dinosaur diets reveals a world far more complex and alien than we ever imagined. These magnificent creatures thrived for over 160 million years without ever seeing a blade of grass, creating intricate relationships with plants that shaped the evolution of life on Earth. Their story reminds us that nature is endlessly creative, finding ways to build thriving ecosystems from whatever materials are available. What other assumptions about the ancient world might be completely wrong?