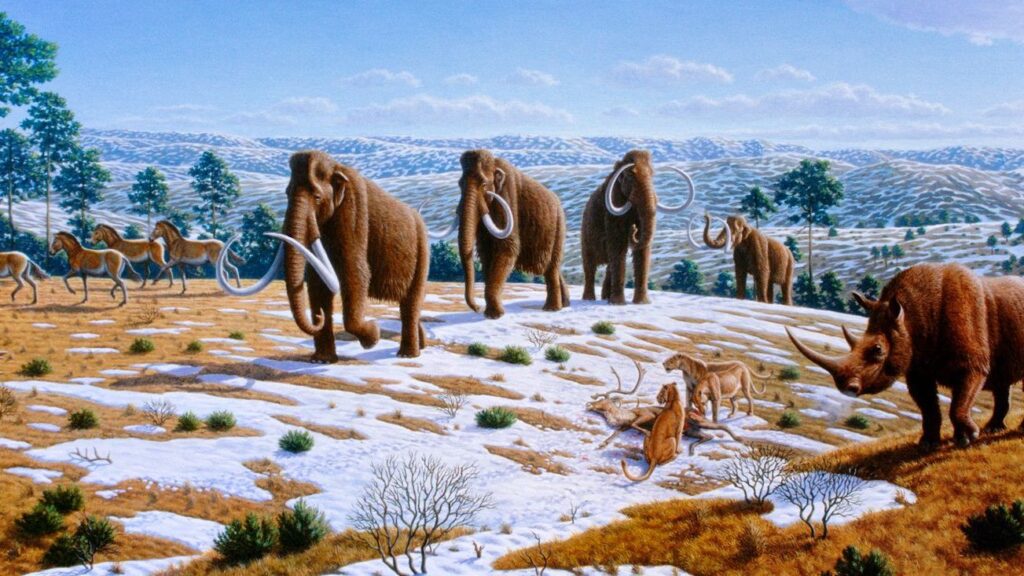

Picture this. You’re standing on a vast, frozen grassland where temperatures plunge far below freezing. Glaciers tower around you. The landscape stretches endlessly, white and harsh. Here’s the thing though: this wasn’t an empty wasteland. It was actually teeming with life. We’re talking about the Ice Age in North America, a time when enormous creatures roamed through conditions that would make most modern animals shiver and give up. Yet these prehistoric mammals found ways to thrive.

So how did they do it? How did these ancient beasts navigate such brutal, unforgiving conditions when even today’s wildlife would struggle? Let’s dig into the remarkable survival strategies that allowed these giants to dominate the Ice Age landscape.

Thick Fur and Layers of Fat Became Natural Insulation

Woolly mammoths developed thick coats of hair, large fat reserves, and specially adapted blood that helped them endure the frigid temperatures of Ice Age America. Think of it like wearing the world’s best winter coat combined with a built-in heating system. These massive animals weren’t just surviving the cold – they were engineered for it.

Woolly mammoths evolved with thick outer coats consisting of guard hairs up to 90 centimeters in length and shorter underwool that worked together to trap heat close to their bodies. Mastodons had short ears and tails to help conserve heat and a thick coat of fur, making them hardy and tough enough to withstand cold temperatures and fend off predators. The smaller the appendages, the less heat lost to the environment. Honestly, it’s a simple but brilliant adaptation.

Specialized Diets Helped Navigate Changing Food Sources

Survival wasn’t just about staying warm. You needed to eat, and finding food under several feet of snow required serious ingenuity. Different species developed distinct feeding strategies that allowed them to carve out their own niches in the frozen ecosystem.

The diet of the woolly mammoth was mainly grass and sedges, which they could dig out from beneath snow using their massive curved tusks. Meanwhile, mastodons took a different approach. The mastodon had teeth with tall ridges and cones, which were used for browsing on softer plant material like fruits, leaves, and twigs. This dietary flexibility meant different species weren’t competing for the same resources. Some grazed, others browsed, and everyone found their place at the table.

Dietary flexibility was crucial for survival, allowing animals to exploit available food sources even when resources were scarce. It’s hard to say for sure, but this adaptability likely made the difference between extinction and persistence for many species.

Migration Patterns Followed Shifting Climate Zones

Some animals migrated to follow the availability of food resources, a strategy that proved essential during the Ice Age’s dramatic climate swings. Reindeer and caribou followed the availability of food resources, moving south during winter and north during summer, with their thick fur and specialized hooves providing insulation and traction in snowy conditions.

American mastodons traveled extreme distances in response to dramatic climate change and melting ice sheets, from warmer environments to the northernmost parts of the continent, though populations that headed north were less genetically diverse. Let’s be real: migration wasn’t a casual stroll. These were massive journeys covering hundreds, sometimes thousands of miles. Yet it allowed animals to track favorable conditions rather than trying to endure the worst extremes in one location.

Social Behavior Provided Protection and Warmth

Many Ice Age mammals didn’t face the cold alone. Musk oxen formed tight-knit herds for protection and warmth, with their long, shaggy coats providing excellent insulation. Picture dozens of these massive, woolly creatures huddling together during blizzards, sharing body heat while their combined vigilance kept predators at bay.

While most scientists believe that mammoths lived in matriarchal herds like modern elephants, providing social structure that helped protect vulnerable young. Fossils of dire wolves and saber-toothed cats together outnumber herbivores about nine to one at La Brea, leading scientists to speculate that both predators may have formed prides or packs. Even the fiercest predators understood strength in numbers.

Physical Adaptations Created Ice Age Specialists

Beyond fur and fat, many animals developed highly specialized physical features. Woolly mammoths had ears and tails that were short to minimize frostbite and heat loss, along with long, curved tusks and four molars that were replaced throughout their lifetime as they wore down from grinding tough vegetation.

The short-faced bear could reach speeds topping 40 miles per hour with its powerful sense of smell to detect nearby carcasses, and its speed and size to chase off competition. Talk about an apex predator perfectly designed for its environment. Scimitar-toothed cats likely had very good daytime vision, displayed complex social behaviors, and had genetic adaptations for strong bones and cardiovascular systems, meaning they were well suited for endurance running.

Refugia and Sheltered Habitats Offered Sanctuary

Not every animal could handle the full brunt of glacial conditions, so some found shelter in special pockets of the landscape. Areas known as refugia are locations where species retreated to survive during periods when environmental conditions were unfavorable elsewhere, probably the warmest areas or places where it was easiest for animals to find food.

Arctic ground squirrels were well equipped for survival in glacial times as they spend the long winters hibernating underground. While the giants battled conditions above ground, smaller mammals simply went to sleep and waited out the worst of it. Species such as pygmy shrew and common vole had been restricted to sheltered areas such as deep valleys in northern Europe, small enclaves in otherwise inhospitable glacial landscapes. Sometimes survival meant finding the right hiding spot.

The End Came Despite Millennia of Success

Here’s what makes the Ice Age extinctions so puzzling. Most of these ice age animals had endured at least 12 previous ice ages and did not go extinct until the very end. The Pleistocene Epoch ended around 11,700 years ago with an extinction event that eliminated much of the world’s megafauna, with about 73 percent of large herbivore species vanishing in North America.

The timing and severity of extinctions varied by region and are generally thought to have been driven by humans, climatic change, or a combination of both. Long-distance dispersal was crucial for the long-term persistence of megafaunal species living in the Arctic, and such dispersal was only possible when their rapidly shifting rangelands were geographically interconnected, ending fatally when geographic ranges became permanently fragmented as rising seas and spreading wetlands blocked traditional migration routes.

Conclusion: Lessons From Ancient Survivors

The prehistoric mammals of Ice Age America were nothing short of remarkable. They weathered extreme cold with biological adaptations that seem almost engineered for survival. Thick fur, specialized diets, complex social structures, and incredible migration patterns allowed them to flourish where few modern species could exist. Yet despite surviving roughly a dozen previous ice ages, something about this final transition proved insurmountable.

Some animals seemed able to tolerate ice age conditions while others withdrew to refugia, with modern humans particularly surprising in this group as ancestors originated in Africa and it seemed unlikely they were resilient to cold climates. The story reminds us that adaptability has limits, and even the most successful survival strategies can fail when conditions shift too rapidly or dispersal routes disappear. What do you think was the final straw for these magnificent creatures? Share your thoughts.